Abdominal ultrasonography is very useful for diagnosing acute appendicitis and has 59-96% sensitivity and 83-98% specificity. The aim of the present study was to determine the diagnostic yield of abdominal ultrasound imaging for acute appendicitis and identify the patient subgroups with the best results.

Materials and methodsPatients at a general hospital that underwent appendectomy due to the clinical suspicion of appendicitis, who also had a diagnostic radiologic study, within the time frame of January 2007 to December 2010, were analyzed. Ultrasound studies were considered positive when there were radiologic signs suggestive of acute appendicitis. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the diagnostic study were determined through the logistic regression method.

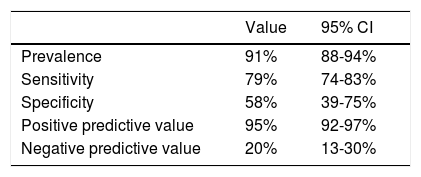

ResultsA total of 646 patients were operated on due to clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis. A diagnostic abdominal ultrasound study was carried out on 383 (59.3%) of those patients, resulting in 79% sensitivity (74-83, 95% CI), 58% specificity (39-75, 95% CI), 95% positive predictive value (92-97, 95% CI), and 20% negative predictive value (13-30, 95% CI).

ConclusionsAbdominal ultrasound imaging in patients with a high suspicion of appendicitis had a mediocre diagnostic yield, but better results could be achieved in different specific subgroups.

La ecografía abdominal es muy útil para el diagnóstico de apendicitis aguda, con una sensibilidad del 59-96% y una especificidad del 83-98%. El objetivo del trabajo fue establecer la capacidad diagnóstica de la ecografía abdominal para apendicitis aguda e identificar los subgrupos de pacientes en la cual obtendríamos unos mejores resultados.

Material y métodosPacientes intervenidos de apendicectomía por la sospecha clínica de apendicitis en un centro desde enero del 2007 hasta diciembre del 2010 a los que se les realizará una técnica radiológica diagnóstica. Se considerará positiva la ecografía cuando se observen signos radiológicos indicativos de apendicitis aguda. La sensibilidad, la especificidad y los valores predictivos de una prueba diagnóstica se estimarán usando técnicas de regresión logística.

ResultadosSeiscientos cuarenta y seis pacientes fueron intervenidos por la sospecha clínica de apendicitis aguda. En 383 casos (59.3%) se realizó una ecografía abdominal para el diagnóstico. Se obtuvo una sensibilidad del 79% (IC del 95%: 74-83), una especificidad del 58% (IC del 95%: 39-75), un valor predictivo positivo del 95% (IC del 95%: 92-97) y un valor predictivo negativo del 20% (IC del 95%: 13-30).

ConclusionesLa ecografía abdominal en pacientes con alta sospecha de apendicitis presenta una rentabilidad mediocre. Sin embargo, estas cifras pueden mejorarse en distintos subgrupos concretos.

Acute appendicitis is one of the most frequent pathologies affecting humans, with an estimated 8% of the world population operated on for that condition at some point in their lives.1 It is the most frequent abdominal emergency, with an incidence of approximately 100 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year in Europe and the United States.2

The diagnosis of acute appendicitis is clinical, and basic radiology and laboratory tests are not essential. There has been a decrease in its severity over the past 30 years, due to its earlier diagnosis and treatment 2 resulting from high clinical suspicion and the development of the imaging techniques of ultrasonography, computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance.

Abdominal ultrasonography is very useful for diagnosing acute appendicitis and different case series have reported sensitivity at 59-96% and specificity at 83-98%.3–6 It is the imaging study of choice due to its low cost and comfort. However, there are several conditioning factors that can alter its diagnostic yield for said diagnosis, such as: sex, obesity determined through body mass index (BMI), perforated appendicitis, and the experience of the radiologist.3,7,8

The aim of the present study was to establish the diagnostic yield of abdominal ultrasonography for acute appendicitis and identify the patient subgroups that have better diagnostic results.

Materials and methodsThe present study included all patients that underwent appendectomy at a general hospital within the time frame of January 2007 to December 2010, due to clinical suspicion of appendicitis, and in whom a diagnostic radiology study was carried out.

The inclusion criteria were: patients above 14 years of age, operated on for clinical suspicion of appendicitis that was confirmed through a radiologic technique. The exclusion criteria were: patients under 14 years of age and those that did not undergo surgical intervention.

The study variables were: age, sex, year of diagnosis, obesity, progression time of appendicitis, use of a radiology study (ultrasonography, CT), a positive radiology study, surgical findings, anatomopathologic study, and the severity of appendicitis (gangrenous, perforated, or with periappendiceal adhesions). Body mass index (BMI) was only available in a small number of patients (11%), and therefore obesity was determined by weight as 70kg in females and 90kg in males.

The ultrasound studies were carried out utilizing a high-definition apparatus with a 7.5 mHz linear probe and a 3.5 mHz sector-scanning probe. The ultrasound study was considered positive when radiologic signs suggestive of acute appendicitis were observed: target sign, appendix with a diameter larger than 6mm, non-compressible appendix, inflammatory changes in the surrounding fat, increased vascularization viewed in a color Doppler study, or signs of appendiceal perforation.4,7,9,10 Doubtful cases were considered negative. No distinguishing data were obtained in relation to the radiologists performing the studies, other than that they ranged from physicians in training to established radiologists. The definitive diagnosis was made through the anatomopathologic study of the surgical specimen.

The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of a diagnostic test can be calculated using methods of logistic regression as described by Coughlin et al.11 A given test can perform very differently, depending on the context of the disease or the patient, and their combination. If binary variables are used, the logistic regression analysis can produce diagnostic rates for each combination of features that, at least theoretically, can influence the diagnostic capacity of the imaging study. In accordance with reports in the literature, in the present study the features that could influence ultrasonographic diagnostic yield were: sex, age, obesity, and clinical progression time. The different analyses were carried out employing the Windows® SPSS version 22 statistics program (IBM®, Armonk, New York, USA).

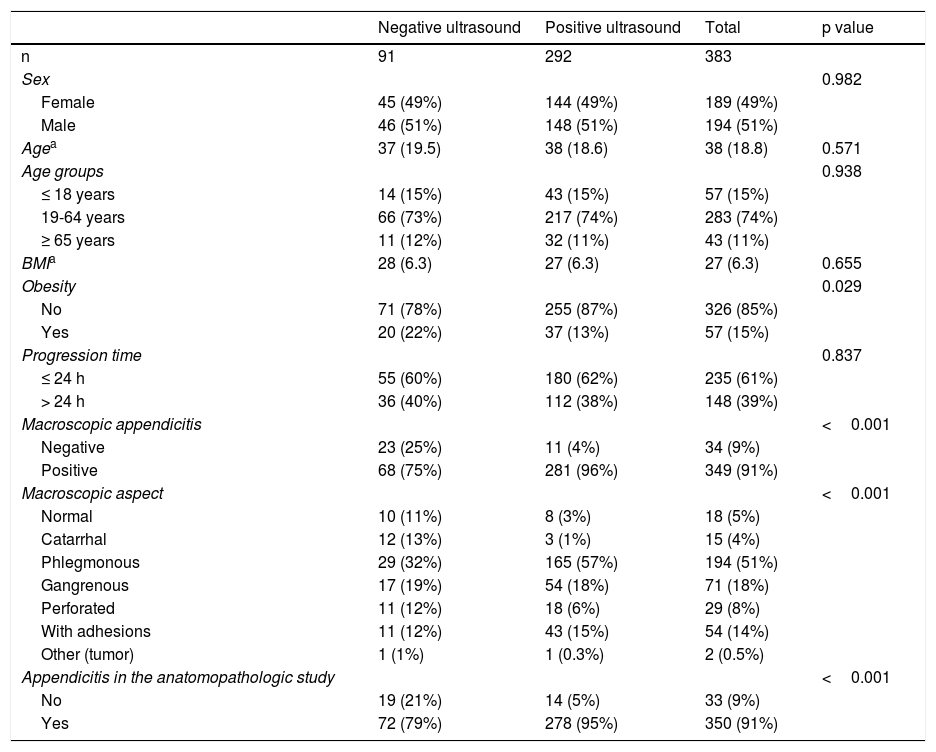

ResultsDuring the 4 years of the study, 646 patients were operated on due to clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis. To confirm the diagnosis, a radiologic study was carried out on 391 of those cases (60.5%). An abdominal ultrasound study was performed on 383 cases (59.3%), 25 patients (3.9%) had an abdominopelvic CT scan, and 17 cases (2.6%) had both studies. By year, diagnostic radiologic studies were carried out in 2007 on 110 patients (66.3% of the total cases of appendicitis), in 2008 on 117 cases (59.4%), in 2009 on 96 cases (56.5%), and in 2010 on 68 cases (60.2%). Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the study sample. The two groups of patients were comparable in relation to sex, age, BMI, and clinical progression time. There were statistically significant differences associated with obesity. There were more obese patients in the group with a positive ultrasound study than in the group with a negative ultrasound study. As would be expected, the patients with a negative ultrasound study had a higher number of normal appendices in the anatomopathologic study, as well as a normal macroscopic aspect during surgery. However, there was also an elevated number of cases of perforated appendicitis in the negative ultrasound study group.

Clinical characteristics of the study sample.

| Negative ultrasound | Positive ultrasound | Total | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 91 | 292 | 383 | |

| Sex | 0.982 | |||

| Female | 45 (49%) | 144 (49%) | 189 (49%) | |

| Male | 46 (51%) | 148 (51%) | 194 (51%) | |

| Agea | 37 (19.5) | 38 (18.6) | 38 (18.8) | 0.571 |

| Age groups | 0.938 | |||

| ≤ 18 years | 14 (15%) | 43 (15%) | 57 (15%) | |

| 19-64 years | 66 (73%) | 217 (74%) | 283 (74%) | |

| ≥ 65 years | 11 (12%) | 32 (11%) | 43 (11%) | |

| BMIa | 28 (6.3) | 27 (6.3) | 27 (6.3) | 0.655 |

| Obesity | 0.029 | |||

| No | 71 (78%) | 255 (87%) | 326 (85%) | |

| Yes | 20 (22%) | 37 (13%) | 57 (15%) | |

| Progression time | 0.837 | |||

| ≤ 24 h | 55 (60%) | 180 (62%) | 235 (61%) | |

| > 24 h | 36 (40%) | 112 (38%) | 148 (39%) | |

| Macroscopic appendicitis | <0.001 | |||

| Negative | 23 (25%) | 11 (4%) | 34 (9%) | |

| Positive | 68 (75%) | 281 (96%) | 349 (91%) | |

| Macroscopic aspect | <0.001 | |||

| Normal | 10 (11%) | 8 (3%) | 18 (5%) | |

| Catarrhal | 12 (13%) | 3 (1%) | 15 (4%) | |

| Phlegmonous | 29 (32%) | 165 (57%) | 194 (51%) | |

| Gangrenous | 17 (19%) | 54 (18%) | 71 (18%) | |

| Perforated | 11 (12%) | 18 (6%) | 29 (8%) | |

| With adhesions | 11 (12%) | 43 (15%) | 54 (14%) | |

| Other (tumor) | 1 (1%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Appendicitis in the anatomopathologic study | <0.001 | |||

| No | 19 (21%) | 14 (5%) | 33 (9%) | |

| Yes | 72 (79%) | 278 (95%) | 350 (91%) |

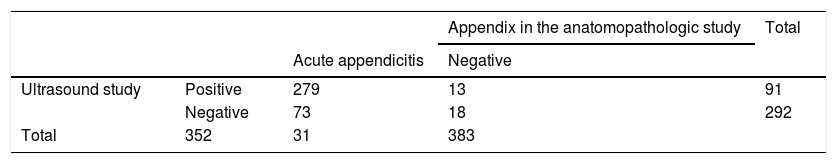

A 2 x 2 contingency table was constructed with the ultrasonography results of the entire study sample, from which the overall diagnostic rates of sensitivity, specificity, and the predictive values were calculated. Tables 2 and 3 describe those data.

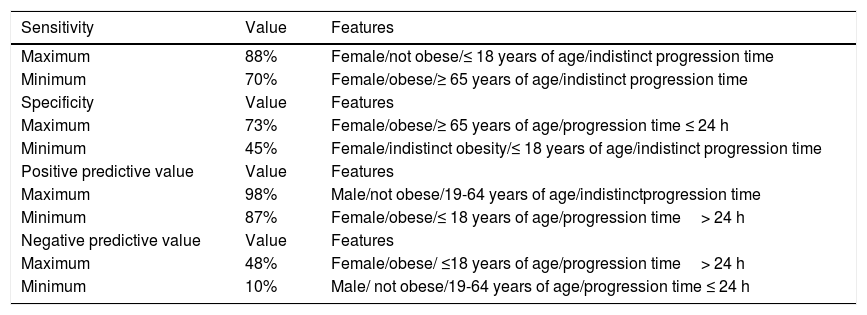

From those results, a logistic regression analysis was carried out, calculating sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values in accordance with combinations of the different study variables: sex, age, obesity, and progression time (Table 4).

Model: Values calculated through logistic regression.

| Sensitivity | Value | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 88% | Female/not obese/≤ 18 years of age/indistinct progression time |

| Minimum | 70% | Female/obese/≥ 65 years of age/indistinct progression time |

| Specificity | Value | Features |

| Maximum | 73% | Female/obese/≥ 65 years of age/progression time ≤ 24 h |

| Minimum | 45% | Female/indistinct obesity/≤ 18 years of age/indistinct progression time |

| Positive predictive value | Value | Features |

| Maximum | 98% | Male/not obese/19-64 years of age/indistinctprogression time |

| Minimum | 87% | Female/obese/≤ 18 years of age/progression time> 24 h |

| Negative predictive value | Value | Features |

| Maximum | 48% | Female/obese/ ≤18 years of age/progression time> 24 h |

| Minimum | 10% | Male/ not obese/19-64 years of age/progression time ≤ 24 h |

The present study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Hospital General de Castellón and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as confidentiality norms.

Discussion and conclusionsAcute appendicitis is the most frequent emergency surgery in developed countries. High clinical suspicion is essential to prevent the progression of cases resulting in appendiceal perforation and diffuse peritonitis. Ultrasound imaging is justified in doubtful cases, in which a clinical diagnosis is not sufficiently reliable.2,5

In diagnostic studies, such as ultrasound imaging, the main aspects to consider are sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV), given that in a patient with abdominal pain suggestive of appendicitis, it is important to accurately rule out appendicitis to prevent unnecessary surgery (surgical intervention being necessary in the cases in which appendicitis cannot be ruled out). To do so, a high level of sensitivity is needed (few a priori false negatives) and an elevated NPV, which confirms a negative result as highly likely. That occurs when both items clearly surpass the value of 80%, in their point estimate or at least in the upper limit of the confidence interval for the population. The statistical significance of those rates of diagnostic efficacy are defined according to whether or not there is a 50% confidence interval. Results are statistically significant in cases in which the confidence interval is not 50%.12

In our analysis, by including only the patients that were operated on, naturally the NPV was low, given that the prevalence of appendicitis was high (91%) and the number of cases with a negative ultrasound study and no appendicitis was low, with a point estimate of 20% and an upper limit of the confidence interval of 30%, with statistically significant differences (because the interval was not 50%). That means that an ultrasound study that is negative for appendicitis is more deceptive than accurate. In relation to sensitivity, values were exceptionally poor, with a point estimate and lower limit of the confidence interval under 80%, with statistically significant differences, signifying that in our case series, the a priori diagnostic capacity to rule out appendicitis was mediocre in the patients with high clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis. Very disparate figures are reported in the medical literature regarding the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography. In a meta-analysis that included 17 studies with 3,358 patients, Orr et al.5 reported sensitivity of 84.7% (95% CI: 81-87.8%) and specificity of 92.1% (95% CI: 88-95.2%). However, there was great heterogeneity among the results of the studies included in the meta-analysis. Giljaca et al.3 conducted a meta-analysis of 17 review articles, using stricter inclusion criteria, and reported sensitivity of 69% (95% CI: 59-78%), specificity of 81% (95% CI: 73-88%), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 92% (95% CI: 88-95%), and a NPV of 55% (95% CI: 46-63%), which are figures similar to those of our study. Specificity is the a priori capacity to confirm a positive diagnosis that will then corroborate the PPV, as long as there is an elevated disease prevalence. The specificity in our study was also mediocre, but due to the elevated disease prevalence, even under those circumstances, a positive diagnosis was very reliable.

A logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the different covariables that could influence the diagnostic yield of ultrasound imaging. Good sensitivity was obtained for the imaging study in non-obese females under 18 years of age. Progression time produced no influence. Specificity of the ultrasound studies in the entire study sample presented poor diagnostic yield with figures below 60%. After performing logistic regression techniques, mediocre diagnostic yield was obtained in obese females above 65 years of age, with a short period of clinical progression. In general, the PPV was excellent, with values above 95%, but better results were obtained in middle-aged obese males. Progression time was indistinct. The NPV results, like the overall data, were poor, but better results were obtained in obese females under 18 years of age, with more than 24h of clinical progression.

Ultrasound imaging plays an important role in fertile females, given that a greater number of diagnostic errors can be committed in that patient subgroup, especially in patients with acute gynecologic pathology. At the same time, the innocuousness of the study makes it the imaging examination of choice in those patients.7

Female sex has been identified in different studies6 as a factor that reduces the diagnostic yield of ultrasonography. In addition, identification of the appendix has been shown to be difficult in patients with a high BMI or in very muscular patients.8

The main limitations of the present study were the reduced evidence inherent in the retrospective study design and the fact that ultrasound is an operator-dependent study,13 even though all the examinations were performed at the same radiology service, utilizing the same diagnostic criteria. We evaluated the overall results of a radiology service, but due to the difficulty involved, we could not analyze the role of the different radiologists (with different levels of experience and training), which would have been of great interest. As stated in the Materials and Methods section, weight was the only measure of obesity, given that the retrospective study design did not allow the BMI to be calculated in the majority of cases, which would have been a better obesity grade marker than weight alone.

In conclusion, the diagnostic yield of abdominal ultrasonography in patients with a high suspicion of appendicitis was mediocre, but better results could be achieved in different specific subgroups.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the Research and Ethics Committee of the Hospital General de Castellón and the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data, preserving patient confidentiality and anonymity.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Fortea-Sanchis C, Escrig-Sos J, Forcadell-Comes E. Rentabilidad de la ecografía abdominal para el diagnóstico de apendicitis aguda. Análisis global y por subgrupos. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2020;85:12–17.