Chylous ascites is a rare cause of ascites resulting from the accumulation of lymph in the abdominal cavity. It has different etiologies that interrupt the lymphatic flow. Diagnosis is made when a milky or turbid fluid is observed, with a triglyceride concentration ≥ 110mg/dl.1,2 The diagnostic criterion for some authors is a serum triglyceride to fluid ratio > 1.0, a cholesterol ratio < 1.0, a leukocyte count ≥ 300 cells/mm3, and/or a predominance of lymphocytes with negative culture and cytology.3 Its incidence varies from 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 187,000 referral hospital admissions.2,4 Its causes are varied and cirrhosis is responsible for 0.5% of cases.5

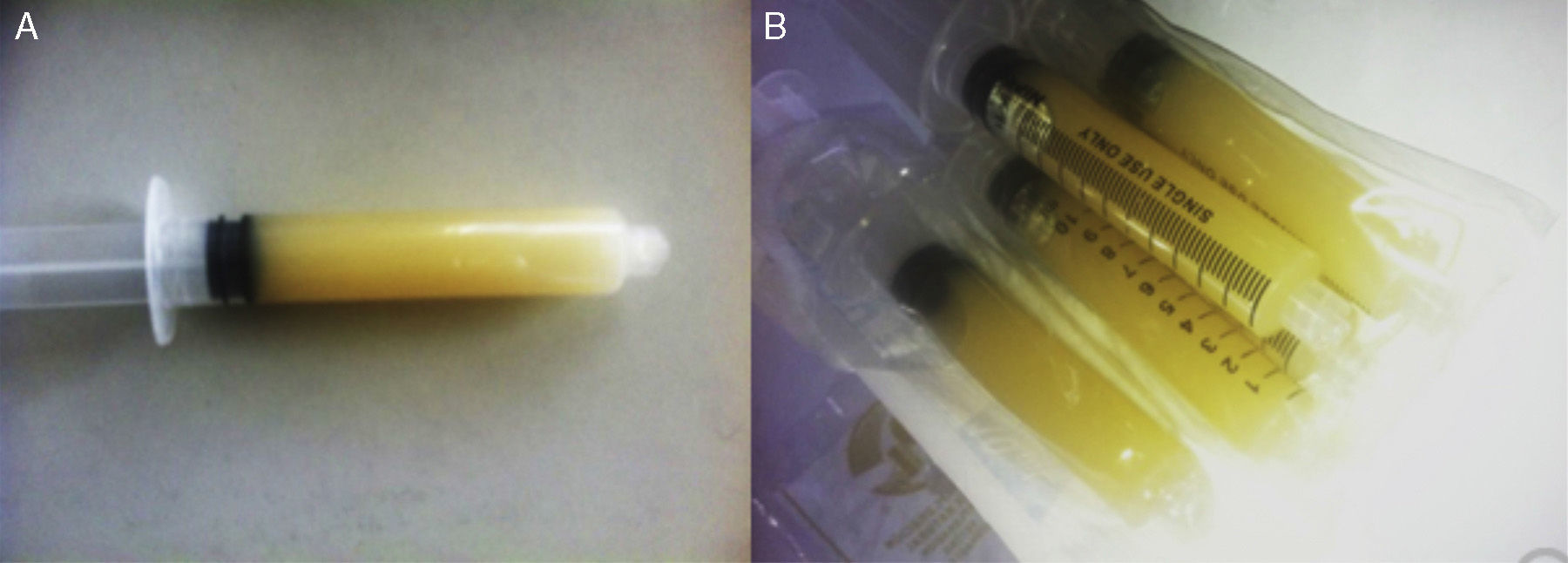

We present herein the case of an 84-year-old man with a past history of diabetes and high blood pressure. Five years prior he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver due to alcohol. His current illness began 5 months before his hospital admission, characterized by lower limb edema. During the last 2 weeks he presented with a progressively increasing abdominal perimeter that resulted in dyspnea, and was the reason he sought medical attention. He had not consumed alcohol for the last 4 years and had not experienced abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed muscle atrophy with no jugular plethora. He had rhythmic heart sounds and there were no pleuropulmonary alterations. The patient's abdomen was prominent with water dullness, with no visceromegaly. Lower limb edema reached the thighs. Upon his admission, paracentesis was carried out, obtaining a milky fluid (Fig. 1).

Laboratory work-up upon admission showed: hemoglobin 15.2g/dl, platelets 133,000, leukocytes 5,700 with 80% neutrophils, 14% lymphocytes, and 6% monocytes, glucose 379mg/dl, creatinine 0.86mg/dl, BUN 21mg/dl, urea 44.9mg/dl, total serum cholesterol 151mg/dl, serum triglycerides 111mg/dl, amylase 42 IU/l, and lipase 12 IU/l. LFT with AST 41 U/l, ALT 21 U/l, alkaline phosphatase 116 UI/l, albumin 2.8g/dl, and globulins 2.9g/dl. Alpha-fetoprotein 3.65μg/l (normal value: 0-5), carcinoembryonic antigen 4.4μg/L (normal value: 0-3), Ca 19-9 of 23 IU/ml (normal value: 0-37), and adenosine deaminase 7.6 IU/l (normal value: 0-6.7). Ascitic fluid cytochemistry with a pH of 6.5, cells 768 with 95% lymphocytes, glucose 225mg/dl, proteins 1,264mg/dl, and triglycerides 305mg/dl. Ascitic fluid cytology was negative for neoplastic cells. Blood culture and ascitic fluid culture were negative.

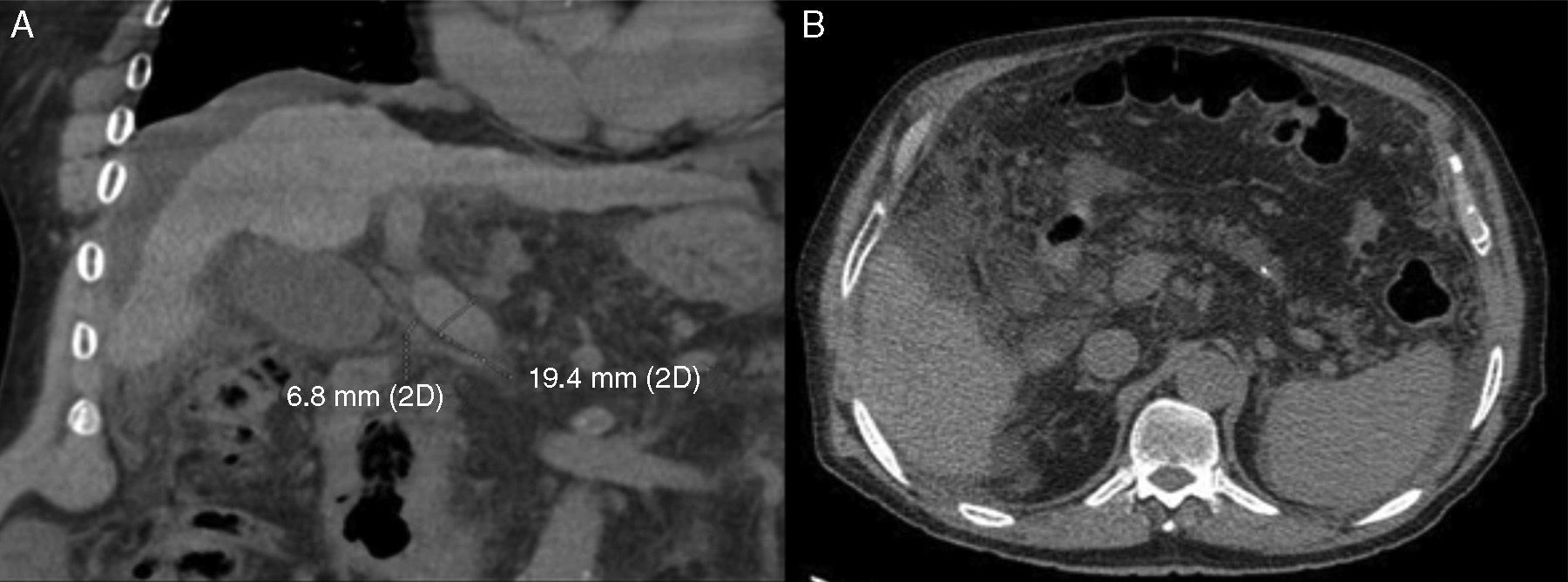

Ultrasound imaging revealed a small liver with irregular edges, vena porta with a 13mm diameter, and abundant ascitic fluid. Tomography scan identified abundant ascitic fluid, a small and irregular liver, vena porta with a 19.4mm diameter with no thrombi, normal pancreas, and no adenomegalies (Fig. 2).

Endoscopy found large esophageal varices in the distal two-thirds, slight hypertensive portal gastropathy changes in the fundus and body and erosive gastropathy in the antrum. Colonoscopy identified telangiectasia, diverticular disease of the left colon, and internal hemorrhoids.

The patient was treated with a normal protein and low-fat diet, paracentesis with the administration of albumin, and later with diuretics. At present his response is unsatisfactory, given that moderate lower limb edema persists, as well as the ascites, requiring repeat paracentesis.

There are multiple causes of chylous ascites, and the most frequent are malignant neoplasias, especially lymphoma. Others include breast and pancreatic neoplasia. The condition can have an inflammatory disease origin, such as pancreatitis, or a traumatic origin, such as constrictive pericarditis, observed after abdominal surgery or blunt trauma. These causes were satisfactorily ruled out in our patient, and only liver cirrhosis was documented as the cause of chylous ascites, which is seen in 0.5-1% of cases. Due to the poor response in our patient, other measures will be carried out, such as middle-chain triglyceride or octreotide use.6,7 Another therapeutic option is the administration of orlistat, which has been reported to reduce the quantity of triglycerides in the ascitic fluid in patients with cirrhosis.8

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Piña-Pedraza JP, Álvarez-Avalos L, Vargas-Espinosa JM, Salcedo-Gómez A, Carranza-Madrigal J. Ascitis quilosa secundaria a cirrosis hepática. Reporte de un caso. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2015;80:285–287.