The word amyloidosis refers to a pathologic finding that encompasses a heterogeneous spectrum of etiologies and clinical presentations. The main characteristic of amyloidosis is the deposition of insoluble extracellular protein fragments in various organs, abnormally folded in such a way that they are resistant to digestion1. Those deposits affect both the structure and function of the compromised organs.

In the gastrointestinal tract, amyloid deposition is produced in the muscularis mucosae, very close to the vasculature, nerves, and nerve plexuses2. Said deposition increases blood vessel fragility, hinders intrinsic peristalsis, and reduces intestinal wall distensibility3. Those events explain the symptoms of gastrointestinal amyloidosis of weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, malabsorption, esophageal reflux, and different grades of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding4,5, with severe bleeding being a rare manifestation5. We report herein the case of a patient with signs of gastric amyloidosis who presented with gastrointestinal bleeding.

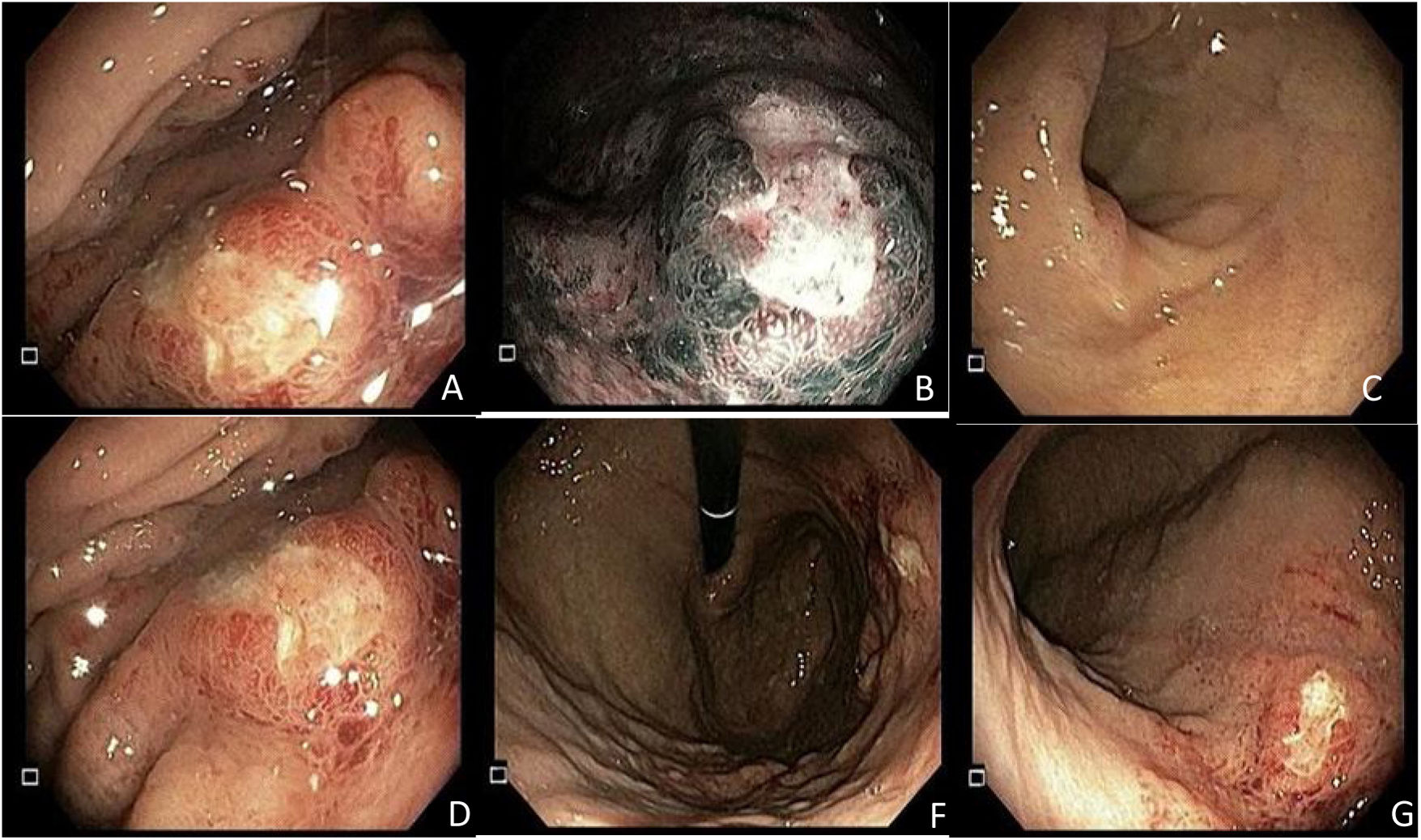

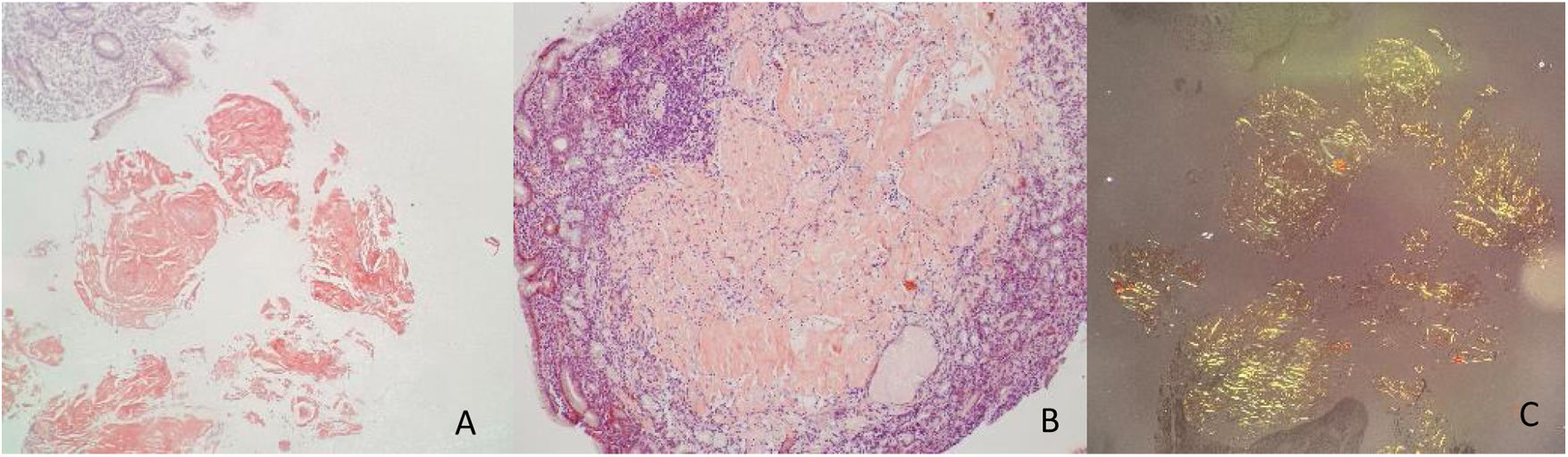

A 59-year-old man, with an unremarkable past medical history, came to the emergency department on two occasions due to epigastric pain, melena, diaphoresis, and dyspnea, of seven-day progression. The initial evaluation showed anemia (hemoglobin: 9.7 g/dl) and hemodynamic stability, for which he received outpatient management with oral omeprazole. He sought medical attention 48 h later because of hematochezia. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy identified a 10 × 10 mm lesion with a neoplastic aspect in the gastric body, toward the greater curvature, with surrounding infiltrate-like mucosa (Fig. 1). Numerous biopsy samples were taken that contained deposits of pale pink interstitial and extracellular material with a thick and cracked hyaline appearance. Congo Red staining produced a salmon-pink color that, under polarized light, showed apple-green birefringence (Fig. 2).

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, showing a 10 mm × 10 mm lesion with a neoplastic appearance in the gastric body toward the greater curvature. (1A) Elevated lesion in the greater curvature, with a depressed center and irregular edges, Paris 0-IIa + 0-Iic, under direct light. (1B) Lesion with a trabecular surface, with branched and irregular areas, of heterogeneous color and a vascular pattern with areas presenting with amputated vessels under narrow band imaging (NBI), in the greater curvature of the gastric body. (1C) Gastric antrum with no apparent endoscopic lesions. (1D) Lesion viewed from the lesser curvature, with no magnification. (1F) Gastric retroflexion in which the lesion and gastric fundus with normal mucosa can be seen. (1G) Direct view of the entire gastric body.

In conjunction with the hematology service, the possibility of secondary amyloidosis was evaluated, with no signs of a monoclonal peak. Strikingly, there was a slight increase in the Kappa light chains, with respect to the Lambda chains, in values not consistent with immunoglobulin amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis, and so the conclusion was a single gastric amyloidoma. At a multidisciplinary meeting, conservative management with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and endoscopic follow-up was decided upon. Endoscopic follow-up at eight weeks showed improvement in the initial lesion, and control biopsies were again consistent with amyloidoma, with no changes regarding the previous biopsies. Endoscopic ultrasound identified no signs of deep layer involvement, the presence of perilesional adenopathies, or subepithelial masses. The follow-up results at seven months were favorable patient progression and no new episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding. The latest endoscopy done four weeks ago revealed no changes in the previously described lesion.

The presence of amyloidoma in the gastrointestinal tract tends to be systemic. Localized gastrointestinal amyloidosis, with no evidence of other organ involvement or of associated plasma cell dyscrasia, is rare and does not tend to be life-threatening6. The case reported herein, in which an amyloidoma restricted to the gastrointestinal system was diagnosed, falls within the published statistics of other countries. In a retrospective review of 2,334 patients with amyloidosis that were evaluated at a single referral center over a 13-year period, 3.3% of the cases had gastrointestinal involvement, confirmed by biopsy7. Of those patients, only 21% had amyloidosis circumscribed to the gastrointestinal tract.

Therapy varies significantly, depending on the cause and type of amyloid protein deposition in the tissues. Gastrointestinal complications are treated with symptom control. Localized amyloidosis is characterized by AL amyloid deposition restricted to the gastrointestinal tract. Asymptomatic patients require no intervention and observation is essential. However, patients with recurrent or severe symptoms may require surgery for localized excision of the compromised tissue8. The challenge is deciding which patients are suitable for follow-up and which can benefit from early surgical intervention. The present case was analyzed by different specialists who determined that the patient would benefit from the conservative management of watchful waiting, given that gastric involvement was extensive, and a surgical intervention would require subtotal gastrectomy, a major procedure with an important complication rate. The favorable progression of symptom management with a PPI, the nonrecurrence of bleeding, and the patient’s current asymptomatic status were taken into account. At present, follow-up results have been favorable.

Ethical considerationsTo carry out the present document, a written statement of informed consent was signed by the patient. Approval by the Bioethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana was not required, and according to the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 008430 of October 4, 1993, the publication presented herein is considered low-risk research.

Financial disclosureNo funding was received for the preparation of the present article, from the participating institutions.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Hani AC, Tobón A, Vargas MJ, Muñoz OM. Sangrado gastrointestinal como primera manifestación de amiloidoma gástrico: reporte de caso. Rev Gastroenterol Méx. 2022;87:503–505.