Cirrhosis of the liver is a serious public health problem worldwide, with regional variations determined by cultural factors and economic development.

AimTo know the characteristics of the social, cultural, and economic factors of the patients with cirrhosis of the liver in Veracruz.

Materials and methodsA multicenter, retrolective, relational research study was conducted on patients with cirrhosis of the liver at 5 healthcare institutions in Veracruz. The variables analyzed were etiology, age, sex, civil status, educational level, occupation, and income. Descriptive and inferential statistics were utilized, and statistical significance was set at a p < 0.05. The Windows IBM-SPSS version 25.0 program was employed.

ResultsA total of 182 case records of patients with cirrhosis of the liver were included. The etiologic factors were chronic alcohol consumption (47.8%), viral disease (28.5%), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (8.79%), autoimmune liver disease (4.4%), cholestasis (1.64%), and cryptogenic liver disease (8.8%). Mean patient age was 66.14 ± 13.91, with a predominance of men (58.79%). In comparing the socioeconomic and cultural factors related to etiology, secondary and tertiary education and singleness were statistically significant in male alcoholics (p < 0.05), viral diseases and NAFLD were significantly associated with women with no income (p < 0.05), cryptogenic liver disease was significantly associated with women (p < 0.05), and cholestasis and autoimmune liver disease were not significantly associated with any of the factors.

ConclusionsThe study results revealed the influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors related to the different causes of cirrhosis of the liver in our environment.

La cirrosis es un problema grave de salud pública a nivel mundial con variaciones regionales determinadas por factores culturales y su desarrollo económico.

ObjetivoConocer las características de los factores socio/culturales y económicos de los pacientes con Cirrosis en Veracruz.

Material y métodosEstudio retrolectivo, multicentrico y relacional en pacientes con cirrosis en 5 instituciones de Salud de Veracruz; Las variables analizadas fueron: etiología, edad, sexo, estado civil, escolaridad, ocupación y remuneración económica. Se utilizó estadística descriptiva e inferencial para la obtener X2, con nivel de significancia de 0.05, se empleó el ordenador IBM-SPSS, versión 25.0 para Windows.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 182 expedientes con cirrosis, la etiología fue: consumo crónico de alcohol (47.8%), enfermedad viral (28.5%), enfermedad hepática grasa no alcohólica (EHGNA) (8.79%), autoinmune (4.40%), colestasis (1.64%) y criptogénica (8.8%); la edad promedio fue 66.14 ± 13.91 años con predominio del sexo masculino (58.79%); al comparar los factores socioculturales y económicos en relación a su etiología observamos que en los alcohólicos el sexo masculino, la educación media y superior y la soltería fueron estadísticamente significativa al resto (p < 0.05), las enfermedades virales y EHGNA se asociaron con el sexo femenino y sin ingreso económico (p < 0.05), la criptogénica se asoció únicamente con el sexo femenino de manera significativa (<0.05) y en la colestasis y autoinmune no se observó asociación significativa con ninguno de los factores.

ConclusionesLos resultados permiten conocer la influencia de los factores socioeconómicos y culturales presentes en los diferentes agentes etiológicos de la cirrosis en nuestro medio.

Cirrhosis is the final stage of different slowly progressive liver diseases. Because of its elevated morbidity and mortality rates, it is a major public health problem worldwide, holding third place as a cause of death in men, and seventh place in women.1–2 It is the fifth cause of death in the United States and Europe,3–6 and in 2014, it was the fourth cause of death in Mexico. The estimate for Mexican patients with cirrhosis of the liver in 2020 is 1,496,000, and 1,866,000 new cases are calculated for 2050.7–10

Cirrhosis of the liver is a multifactorial disease. In adults, the majority of cases are associated with chronic alcohol consumption and diseases due to hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus. In recent decades, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has gained in importance, whereas autoimmune liver diseases and cholestasis have been less frequent. When an etiologic agent cannot be identified, which occurs in 10 to 12% of cases, the cause is considered cryptogenic liver disease.11–19 Cirrhosis tends to be diagnosed between the fifth and seventh decades of life. It is predominant in men, when the causal agent is alcoholism, and in women, when due to viral diseases or NAFLD.

Different socioeconomic situations and cultural patterns worldwide have been considered determining factors in the prevalence of cirrhosis of the liver.19,20 Given that there are few reports in Mexico in that regard, we believe the present study provides useful information.21–24

The aim of the present study was to know the the socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of patients with cirrhosis of the liver in a Southern/Southeastern population of Mexico.

Materials and methodsType of studyA multicenter, retrolective, relational research study was conducted.

UniverseThe study included patients of both sexes, above 18 years of age, diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver, and seen for the first time at the gastroenterology services of the following main healthcare institutions in the city of Veracruz: the Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad of the Secretaría de Salud (SESVER), the UMAE No. 14 and Hospital General No. 71 of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), the Hospital de Alta Especialidad of the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales para los Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE), the Hospital Naval de Especialidades of the Secretaría de Marina (HNSM), and the Instituto de Investigaciones Médico-Biológicas of the Universidad Veracruzana (UV).

Sample sizeA sample size of 179 patients was calculated, based on the population of interest of the healthcare institutions and the frequency of cirrhosis of the liver in the State of Veracruz, according to data from the INEGI.

Inclusion criteriaPatients above 18 years of age that had a complete case record.

Exclusion criteriaPatients with an incomplete case record.

Variables analyzedThe variables analyzed were age, sex, civil status, educational level, occupation, income, and etiologic agent (classified as chronic alcohol consumption > 140 g/dl of ethanol, positive serologic markers for hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus, and NAFLD associated with metabolic syndrome. When a specific causal agent could not be identified, it was classified as cryptogenic liver disease).

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were employed to obtain the absolute and relative frequencies (number of cases, percentages, and ratios), measures of central tendency (mean), and measures of dispersion (standard deviation, range with minimum and maximum values, and 95% confidence interval). Inferential statistics were utilized to determine the chi-square statistic with nominal and dichotomic variables, odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval, with a level of significance of 0.05. Statistical significance was set at a p < 0.05. The Windows IBM-SPSS, version 24.0 program was employed.

Ethical considerationsThe present study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Bioethics and Research Committee of the School of Medicine of the Universidad Veracruzana, RegiónVeracruz-Boca del Río.

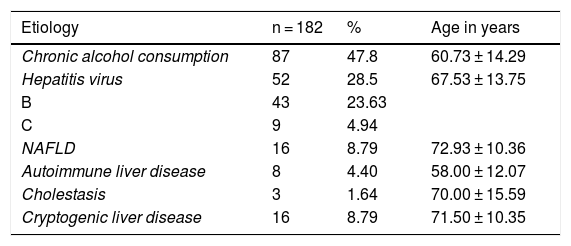

ResultsOf the 229 clinical case records reviewed, 182 (79.47%) met the study requirements. Sixty-four (37.17%) cases corresponded to the IMSS, 46 (25.28%) to the ISSSTE, 23 (12.63%) to the SESVER, 40 (21.98%) to the UV, and 9 (4.94%) to the HNSM. The causal agent in 87 (47.8%) cases was chronic alcohol consumption, viral disease (hepatitis B or C) in 52 (28.5%), NAFLD in 16 (8.8%), autoimmune liver disease in 8 (4.4%), cholestasis in 3 (1.6%), and cryptogenic liver disease in 16 (8.8%) cases. The mean age of all study patients was 66.14 ± 13.91 years (range: 31 to 92 years). In the patients whose disease etiology was chronic alcohol consumption, their mean age was 60.73 ± 14.29 years, the mean age in patients with viral diseases was 67.53 ± 13.75 years, for those with NAFLD, the mean age was 72.93 ± 10.36 years, in patients with cholestasis it was 70.00 ± 15.59, and for those with cryptogenic disease it was 71.50 ± 10.35 (Table 1).

Characteristics of the study sample, according to etiology and age in years.

| Etiology | n = 182 | % | Age in years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic alcohol consumption | 87 | 47.8 | 60.73 ± 14.29 |

| Hepatitis virus | 52 | 28.5 | 67.53 ± 13.75 |

| B | 43 | 23.63 | |

| C | 9 | 4.94 | |

| NAFLD | 16 | 8.79 | 72.93 ± 10.36 |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 8 | 4.40 | 58.00 ± 12.07 |

| Cholestasis | 3 | 1.64 | 70.00 ± 15.59 |

| Cryptogenic liver disease | 16 | 8.79 | 71.50 ± 10.35 |

NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

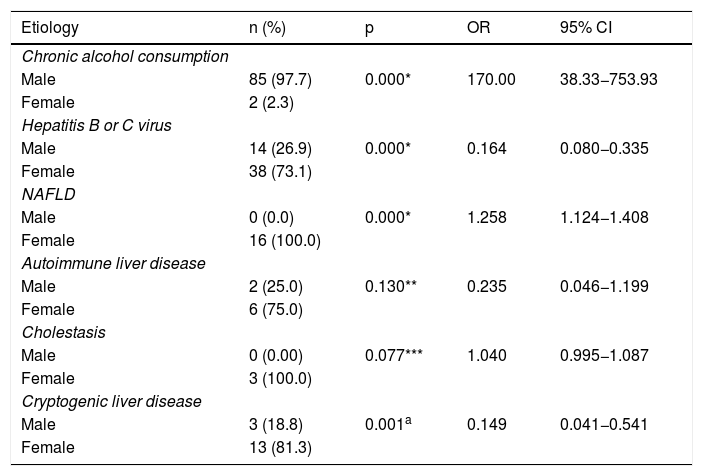

Regarding sex, 104 (57.1%) patients in the study population were men. The number of alcoholic men (85, 97.7%) was significantly higher, compared with alcoholic women (p < 0.000), OR: 170.00, 95% CI: 38.33-753.93. There was a higher, statistically relevant number of women (38, 73.1%) (p < 0.000), OR: 0.164, 95% CI: 0.080-0.335) in the group of patients with viral disease etiology. One hundred percent of the cases of NAFLD were women, with statistical significance (p < 0.000), OR: 1.258, 95% CI: 1.124-1.408). No significant differences between sexes were observed for autoimmune liver disease and cholestasis (p > 0.05) but there were significantly more women (13, 81.25%) in the cryptogenic liver disease group (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Cause of cirrhosis of the liver, according to sex and risk factors.

| Etiology | n (%) | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic alcohol consumption | ||||

| Male | 85 (97.7) | 0.000* | 170.00 | 38.33−753.93 |

| Female | 2 (2.3) | |||

| Hepatitis B or C virus | ||||

| Male | 14 (26.9) | 0.000* | 0.164 | 0.080−0.335 |

| Female | 38 (73.1) | |||

| NAFLD | ||||

| Male | 0 (0.0) | 0.000* | 1.258 | 1.124−1.408 |

| Female | 16 (100.0) | |||

| Autoimmune liver disease | ||||

| Male | 2 (25.0) | 0.130** | 0.235 | 0.046−1.199 |

| Female | 6 (75.0) | |||

| Cholestasis | ||||

| Male | 0 (0.00) | 0.077*** | 1.040 | 0.995−1.087 |

| Female | 3 (100.0) | |||

| Cryptogenic liver disease | ||||

| Male | 3 (18.8) | 0.001a | 0.149 | 0.041−0.541 |

| Female | 13 (81.3) | |||

NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

*Pearson’s chi-square test (p < 0.05), significant.

**Continuity corrected chi-square test (p > 0.05), not significant.

***Fisher’s exact test (p > 0.05), not significant.

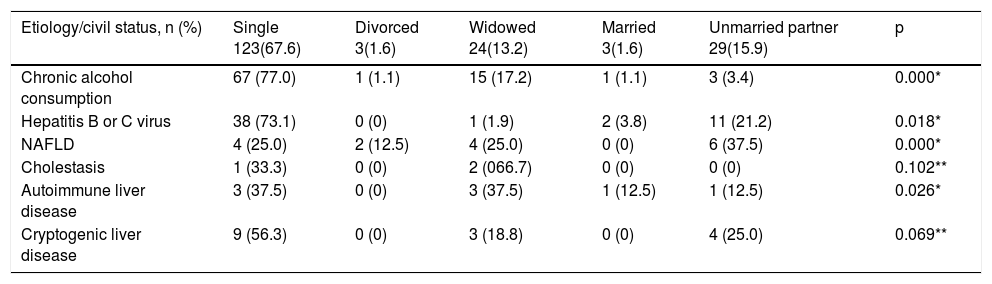

The predominant civil status in the study population was singleness (123, 67.6%), followed by unmarried partner relationship (29, 15.9%), and widowhood (24, 13.2%). Of the 87 persons with chronic alcohol consumption, 67 (77.0%) were single, with a significant association (p < 0.05). There were 52 cases with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus. Thirty-eight (73.1%) of those patients were single, with a significant association (p< 0.018). Of the 16 patients with NAFLD, 6 (37.5%) were unmarried partners. The remaining causal factors analyzed showed similar results (Table 3).

Case distribution, according to civil status.

| Etiology/civil status, n (%) | Single 123(67.6) | Divorced 3(1.6) | Widowed 24(13.2) | Married 3(1.6) | Unmarried partner 29(15.9) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic alcohol consumption | 67 (77.0) | 1 (1.1) | 15 (17.2) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | 0.000* |

| Hepatitis B or C virus | 38 (73.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.8) | 11 (21.2) | 0.018* |

| NAFLD | 4 (25.0) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.000* |

| Cholestasis | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (066.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.102** |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0.026* |

| Cryptogenic liver disease | 9 (56.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (25.0) | 0.069** |

NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

*Pearson’s chi-square (p < 0.05), significant.

**Pearson’s chi-square (p > 0.05), not significant.

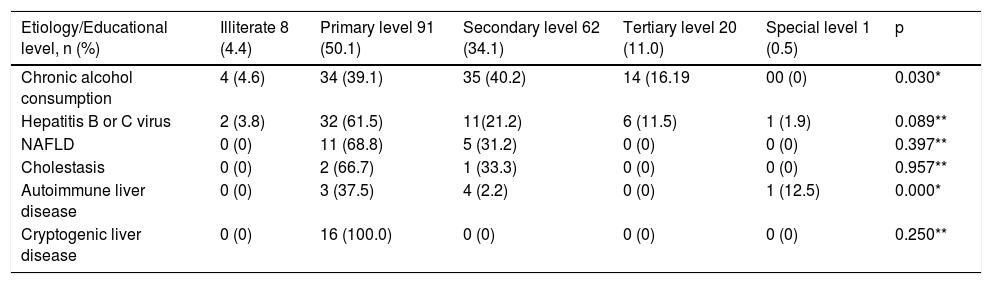

In relation to cirrhosis etiology and educational level, of the 87 cases of chronic alcohol consumption, 34 (39.1%) had a primary education, 35 (40.2%) had a secondary education, and smaller numbers of cases had the remaining levels, resulting in a significant association (p < 0.05). Of the patients with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus, 32 (61.5%) had a primary education and 11 (21.2%) had a secondary education, with no significant difference (p > 0.05). Regarding NAFLD, 11 (68.8%) patients had a primary education and 5 (31.2%) had a secondary education. There were a smaller number of patients with the causal agents of cholestasis and autoimmune liver disease, as well as cryptogenic liver disease, in the primary and secondary education groups (Table 4).

Number of cases by educational level.

| Etiology/Educational level, n (%) | Illiterate 8 (4.4) | Primary level 91 (50.1) | Secondary level 62 (34.1) | Tertiary level 20 (11.0) | Special level 1 (0.5) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic alcohol consumption | 4 (4.6) | 34 (39.1) | 35 (40.2) | 14 (16.19 | 00 (0) | 0.030* |

| Hepatitis B or C virus | 2 (3.8) | 32 (61.5) | 11(21.2) | 6 (11.5) | 1 (1.9) | 0.089** |

| NAFLD | 0 (0) | 11 (68.8) | 5 (31.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.397** |

| Cholestasis | 0 (0) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.957** |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 0 (0) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 0.000* |

| Cryptogenic liver disease | 0 (0) | 16 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.250** |

NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

*Pearson’s chi-square (p < 0.05), significant.

**Pearson’s chi-square (p > 0.05), not significant.

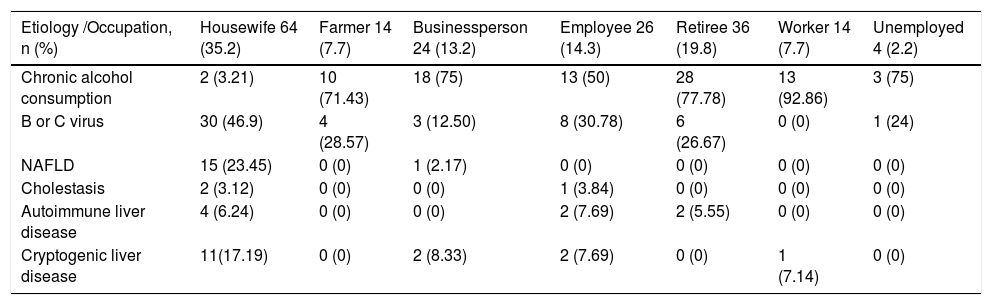

With respect to occupations of the study population, the majority of patients were housewives (64, 35.2%) and retirees (36, 19.8%), followed by employees (26, 14.3%), businesspersons (24, 13.2%), workers (14, 7.7%), and farmers (14, 7.7%). Chronic alcohol consumption was highest in the retirees (27, 31%), and there were no important differences in the rest of the occupations. Of the patients with viral diseases, 17 (32.7%) were housewives, 12 (23.1%) were employees, and there were no relevant variations in the remaining groups. NAFLD was higher in businesspersons (10, 62.5%), followed by housewives (5, 31.3%) and employees (1, 6.3%). There was a reduced number of cases in relation to occupations in the patients with cholestasis, autoimmune liver disease, and cryptogenic liver disease (Table 5).

Occupation and causal agent.

| Etiology /Occupation, n (%) | Housewife 64 (35.2) | Farmer 14 (7.7) | Businessperson 24 (13.2) | Employee 26 (14.3) | Retiree 36 (19.8) | Worker 14 (7.7) | Unemployed 4 (2.2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic alcohol consumption | 2 (3.21) | 10 (71.43) | 18 (75) | 13 (50) | 28 (77.78) | 13 (92.86) | 3 (75) |

| B or C virus | 30 (46.9) | 4 (28.57) | 3 (12.50) | 8 (30.78) | 6 (26.67) | 0 (0) | 1 (24) |

| NAFLD | 15 (23.45) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cholestasis | 2 (3.12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.84) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 4 (6.24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.69) | 2 (5.55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cryptogenic liver disease | 11(17.19) | 0 (0) | 2 (8.33) | 2 (7.69) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.14) | 0 (0) |

NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

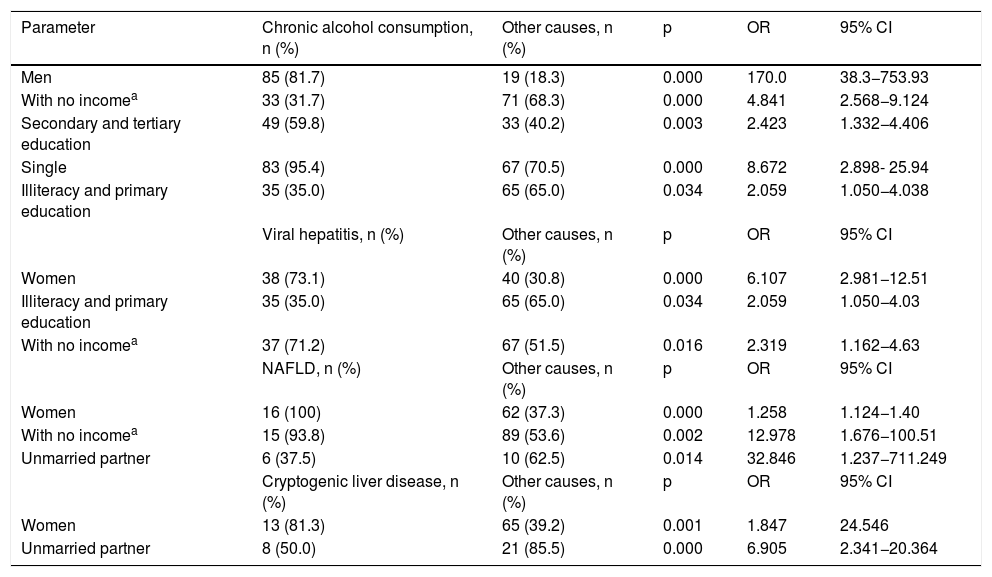

In comparing the study variables with the three main etiologic agents, men were most highly associated with chronic alcohol consumption (85, OR = 170.0), in relation to other causes; women had a 6.107-fold greater probability of presenting with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus; and unmarried partners had a 32.84 greater probability of presenting with NAFLD. The remaining variables were not relevant in relation to a causal agent (Table 6).

Comparison between the three main etiologic agents, with respect to the other causes.

| Parameter | Chronic alcohol consumption, n (%) | Other causes, n (%) | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 85 (81.7) | 19 (18.3) | 0.000 | 170.0 | 38.3−753.93 |

| With no incomea | 33 (31.7) | 71 (68.3) | 0.000 | 4.841 | 2.568−9.124 |

| Secondary and tertiary education | 49 (59.8) | 33 (40.2) | 0.003 | 2.423 | 1.332−4.406 |

| Single | 83 (95.4) | 67 (70.5) | 0.000 | 8.672 | 2.898- 25.94 |

| Illiteracy and primary education | 35 (35.0) | 65 (65.0) | 0.034 | 2.059 | 1.050−4.038 |

| Viral hepatitis, n (%) | Other causes, n (%) | p | OR | 95% CI | |

| Women | 38 (73.1) | 40 (30.8) | 0.000 | 6.107 | 2.981−12.51 |

| Illiteracy and primary education | 35 (35.0) | 65 (65.0) | 0.034 | 2.059 | 1.050−4.03 |

| With no incomea | 37 (71.2) | 67 (51.5) | 0.016 | 2.319 | 1.162−4.63 |

| NAFLD, n (%) | Other causes, n (%) | p | OR | 95% CI | |

| Women | 16 (100) | 62 (37.3) | 0.000 | 1.258 | 1.124−1.40 |

| With no incomea | 15 (93.8) | 89 (53.6) | 0.002 | 12.978 | 1.676−100.51 |

| Unmarried partner | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 0.014 | 32.846 | 1.237−711.249 |

| Cryptogenic liver disease, n (%) | Other causes, n (%) | p | OR | 95% CI | |

| Women | 13 (81.3) | 65 (39.2) | 0.001 | 1.847 | 24.546 |

| Unmarried partner | 8 (50.0) | 21 (85.5) | 0.000 | 6.905 | 2.341−20.364 |

NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Different authors have pointed out that there are epidemiologic variations of liver cirrhosis in different regions of the world, resulting from diverse socioeconomic development and cultural patterns.25–28 Epidemiologic studies have been published in Mexico that show a disease prevalence of 1.4%, with higher regional variations in the north (2.0%), than in the south (1.5%) and center (1.1%) of the country. Cirrhosis of the liver is the fourth cause of general mortality, with a mean patient age of 50.3 ± 12.0 years.29–31

Chronic alcohol consumption holds first place worldwide as the causal agent,16,32 although it is surpassed by viral diseases in Asian and African countries.11,33 It continues to be the primary cause in Mexico, and in our study, it was the most frequent etiologic agent, presenting in 47.81% of cases.34–36 Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections have been in second place for more than three decades. The former is more frequent in India and Africa and the latter is more common in the West.23,33,34 In our study, viral diseases were in second place at 28.5%, and a higher number of patients had hepatitis B virus. NAFLD holds third place17–19,35 and is a great challenge for countries, such as Mexico, given that obesity is in second place worldwide in the adult population and has increased in recent years. In our study, 8.79% of the cases corresponded to NAFLD. A lower frequency of autoimmune liver disease and cholestasis has been reported, and in our case series, they were found at 4.40% and 1.64%, respectively. Finally, 8.79% of the patients in our case series had cryptogenic liver disease.

Regarding sex, we found that men (58.79%) predominated over women (41.21%). However, in the causal agent analysis, men with chronic alcohol consumption predominated (97.7%), but women predominated in relation to all the other etiologic factors, concurring with the results of different authors,36,37 as well as that reported by Meléndez González et al.29 Our results showed that women predominated in viral diseases (73.1%), NAFLD (100%), cholestasis (100%), and cryptogenic liver disease (81.3%), figures that can be explained by the customary lack of healthcare attention sought by men. Nevertheless, Abdo et al.38 reported a 1.4/1 predominance of women over men at the Hospital General de México.

The diagnosis of cirrhosis of the liver tends to be made between the fifth and seventh decades of life. In our case series, the mean patient age was 66.14 ± 13.91 years (range: 31 to 92 years). Ages were lower in relation to autoimmune liver disease etiology (58.00 ± 12.07 years); chronic alcohol consumption (60.73 ± 14.29 years) and viral diseases (67.53 ± 13.75 years) were seen in the seventh decade of life; and NAFLD (72.93 ± 10.36 years) and cryptogenic liver disease (71.50 ± 10.35 years) in the eighth decade of life. There was no statistical significance between any of the groups, similar to that published in the literature.3,7,11,18,21,22,28,35

In our study, singleness was predominant in the chronic alcohol consumption group (77.0%) and the viral disease group (73.1%). The unmarried partner group predominated slightly in NAFLD (37.5%) and was statistically significant, compared with the other etiologies. The remaining statuses were not statistically relevant, given their low number of cases. Comparisons could not be made because of a lack of other studies on etiology and civil status.

Alcohol consumption has been related to educational levels and its consumption is greater in developed countries than in developing countries.21,24,25 In our study, chronic alcohol consumption was significantly higher in the patients with a primary and secondary education. According to the INEGI, the majority of the Mexican population has a low educational level. There was no significant association between educational level and viral diseases, NAFLD, cholestasis, autoimmune liver disease, or cryptogenic liver disease.

Housewives (35.2%) accounted for the principal occupation, followed by retirees (19.8%). Chronic alcohol consumption was mainly related to retirees at 31.0%, compared with the other occupation groups, coinciding with that reported in a study conducted in Chiapas.29

In conclusion, we believe that knowledge of the epidemiologic behavior and socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of the population is extremely useful for designing prevention strategies and carrying out opportune management of cirrhosis of the liver.

In the Mexican environment, as in the rest of the world, chronic alcohol consumption continues to be the main cause of cirrhosis of the liver, with a 170-times greater probability of causing the disease than the other etiologic agents, especially in men. Viral diseases and NAFLD are not as statistically relevant, but they are an important group that is on the rise, given the grade of obesity in Mexican children and adolescents. Our results need to be corroborated by studies with larger numbers of cases.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data or images appear in this article that could identify them. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the school of Medicine of the Universidad Veracruzana.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article, thus no statements of informed consent were required.

Financial disclosureThe study was carried out with funding by the participating institutions.

Conflict of interestDr. José María Remes-Troche is a speaker and advisor for the Takeda and Asofarma laboratories.

The remaining authors have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Roesch-Dietlen F, González-Santes M, Sánchez-Maza YJ, Díaz-Roesch F, Cano-Contreras AD, Amieva-Balmori M, et al. Influencia de los factores socioeconómicos y culturales en la etiología de la cirrosis hepática. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2021;86:28–35.