The majority of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) seek information about their disease on the Internet. The reliability, comprehensiveness, and quality of said information in Spanish has not previously been studied.

Materials and methodsAn analytic observational study was conducted that included YouTube® videos on IBD available in Spanish, describing general characteristics, engagement, and sources. Standard tools for evaluating reliability (DISCERN), comprehensiveness, and overall quality (Global Quality Score, GQS) were employed.

ResultsOne hundred videos were included. Eighty-eight videos consisted of information produced by healthcare professionals (group 1) and 12 included patient opinions (group 2). There were no differences in the median scores for reliability (DISCERN 3 vs 3, p = 0.554) or comprehensiveness (3 vs 2.5, p = 0.768) between the two groups, but there was greater overall quality in the group 2 videos (GQS 3 vs 4, p = 0.007). Reliability was higher for the videos produced by professional organizations (DISCERN 4; IQR 3–4), when compared with healthcare information websites and for-profit agencies (DISCERN 3; IQR 2.5–3.5) (p < 0.001), but the videos with healthcare information website and for-profit sources had a higher quality score (GQS 3 vs 4, p < 0.001). Comprehensiveness scores were similar.

ConclusionThe majority of YouTube® videos in Spanish on IBD have good reliability, comprehensiveness, and quality. Reliability was greater for the videos produced by professional organizations, whereas quality was higher for those created from healthcare information websites and for-profit agencies.

La mayoría de pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) buscan información de su enfermedad en internet. La confiabilidad, exhaustividad y calidad de esta información en español aún no ha sido estudiada.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional analítico que incluyó videos en español sobre EII disponibles en YouTube®. Se describen las características generales, interacción, y fuentes generadoras. Se utilizaron herramientas estandarizadas para la evaluación de confiabilidad (DISCERN), exhaustividad y calidad global (Global Quality Score, GQS).

ResultadosCien videos fueron incluidos. 88% representaban información generada por profesionales en salud (grupo 1) y 12% opiniones de pacientes (grupo 2). No hubo diferencias en la mediana del puntaje de confiabilidad (DISCERN 3 vs 3, p = 0,554), ni exhaustividad (3 vs 2.5, p = 0.768) entre ambos grupos, aunque sí se encontró mayor calidad global en los videos del grupo 2 (GQS 3 vs 4, p = 0.007). La confiabilidad fue mayor para los videos realizados por organizaciones profesionales (DISCERN 4; RIC 3–4) en comparación con las páginas de información en salud y agencias con ánimo de lucro (DISCERN 3; RIC 2.5–3.5) (p < 0.001). Para la evaluación global de calidad la calificación superior para estas últimas fuentes (GQS 3 vs 4, p < 0.001). Los puntajes de exhaustividad fueron similares.

ConclusiónLa mayoría de videos sobre EII en YouTube® en español tienen buena confiabilidad, exhaustividad y calidad. Aunque la confiabilidad fue mayor para organizaciones profesionales, la calidad es superior en páginas de información en salud y agencias con ánimo de lucro.

The use of social media networks (SMNs) is a worldwide phenomenon that has transformed the way in which we consume and utilize information.1 For the year 2021, 70% of adults used SMNs, of which YouTube® stood out (81%), followed by Facebook® (69%) and Instagram® (40%).2 Likewise, close to 70% of patients with chronic diseases use SMNs as a source of information about their medical problems, treatments, and medications.3

The information patients receive from SMNs aids them in understanding their disease and empowering them with respect to their care, facilitating their relationship with healthcare personnel and promoting treatment adherence.4,5 However, many healthcare professionals consider information published on social networking sites to be of low quality, lacking peer review and rigorous evaluation, and are concerned about using SMNs to share information with their patients, arguing that it could have a potentially negative impact on their reputations.6 Such concerns motivate researchers to carry out studies to evaluate the quality and validity of health-related information regarding different chronic diseases on SMNs.6,7

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract that includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Its incidence has been on the rise worldwide, presenting an elevated morbidity burden.8 Up to 75% of patients with IBD have been described to search for specific information about their disease on the Internet.9 Studies conducted more than ten years ago suggest that information about IBD on SMNs in English is generally of low quality and thus is a poor educational resource for patients.10,11 There is little data on the reliability of information about chronic diseases on SMNs in Spanish, and at present, no up-to-date evaluations of the quality of the information regarding IBD that is available on SMNs in Spanish have been carried out.

The aim of the present study was to describe the characteristics of information about IBD found in videos on YouTube®, available in Spanish, evaluating their quality, reliability, and comprehensiveness, utilizing standardized tools, and to determine whether there are differences, with respect to the source of information.

MethodsAn analytic observational study was conducted that evaluated videos on IBD in Spanish, available on YouTube®. The videos that contained information on epidemiology, risk factors, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and other data related to IBD were included in the study. Duplicate videos were excluded.

Data collection methodA YouTube® account was created exclusively for the present study, utilizing a search strategy in incognito mode (Google Chrome browser) to minimize the risk for bias from previous searches. The search was conducted on March 2, 2022, using the terms “inflammatory bowel disease”, “ulcerative colitis”, and “Crohn’s disease”. No filters were used in the search. The first 100 videos in Spanish were selected, based on a previous study that reported that 90% of users only consume the videos presented in the first three pages of video results.12

Information on the type of IBD described in the video (UC, CD, or both), the most likely target audience of the video (patient or healthcare worker, according to the general presentation, description, and source of the video),13 the topics covered, according to their importance for patients and physicians (discussions on symptoms, colonoscopy, or surgery),14,15 the source of the video, the type of video according to content (personal experience, advertising, patient education, alternative treatments, the creation of disease awareness, professional medical education, and others), duration, number of views, subscribers, comments and likes, time on line in days (time between publication and evaluation), and popularity index adjusted by month (defined as the number of likes × 30 days/time on line in days). The source of the video was classified as independent users (individuals from their personal YouTube® accounts), governmental agencies, professional organizations/academic channels (websites created by healthcare professional associations or presentations in medical congresses), healthcare information websites (not associated with professional associations), or for-profit agencies (websites whose purpose was to promote medical services or products). For repeated videos, the number of views were added together and the oldest date on which the video had been uploaded was selected to calculate the time on the Internet. The videos presented in multiple parts were added together and analyzed as a single video. The extraction of information and its classification into the groups described was carried out by one of the researchers.

Evaluation scoresAn initial evaluation determined whether the videos, in general, presented information that could be considered misleading for the patient. The evaluations of reliability, quality, and comprehensiveness were then carried out, utilizing standardized instruments. All the evaluations were peer-reviewed by specialists in internal medicine. When there were differences in the evaluations, the team reviewed the data and reached a consensus. The instruments are described below:

- •

Reliability was defined as the presentation of correct and precise information from a scientific viewpoint on any aspect of the disease. The modified DISCERN tool was utilized, containing five questions and a score ranging from 0 to 5.16

- •

Comprehensiveness was defined as the completeness and detailed description of the information presented about the disease. A tool utilized by Singh et al.17 was employed that consisted of five domains, with a score ranging from 0 to 5.

- •

Overall video quality was evaluated using the Global Quality Score (GQS), a 5-point scale that has now been utilized to assess educational websites for patients with IBD,18,19 and aims to determine just how useful for the patient the information presented is.

The present article was structured according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Statistical analysisThe qualitative variables were described through absolute and relative frequencies. The quantitative variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), considering that they did not have normal distribution. The supposition of normality was evaluated through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, under a significance level of 5% (p < 0.05). The comparison of the categorical variables between groups was carried out using the chi-square test. The video characteristics, according to opinion group (healthcare professionals vs patients) were compared through a Mann-Whitney U test The scores of the scales evaluating reliability, comprehensiveness, and quality were dichotomized into “good” (3 to 5 points) and “bad” (0/1 to 2 points). The agreement assessment of the evaluations was carried out with the dichotomized variable, through the Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The comparison of the video characteristics, according to their sources, was carried out using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The statistical analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software (STATA): Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

Ethical considerationsThe present study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (number FM-CIE-0301-22).

ResultsGeneral characteristicsThe search for the first 100 videos was carried out, resulting in four repeated videos and one without sound, with those five videos being placed on the duplicate list. The final 100 videos included were assessed by two independent evaluators. The level of agreement, determined through the Cohen’s kappa index, showed fair agreement for the reliability evaluation (kappa = 0.32, confidence interval [CI] 0.07−0.56), substantial agreement for the comprehensiveness evaluation (kappa = 0.71, CI 0.58−0.85), and moderate agreement for the quality evaluation (kappa = 0.5, CI 0.27−0.74), each with the statistical significance of p < 0.001.

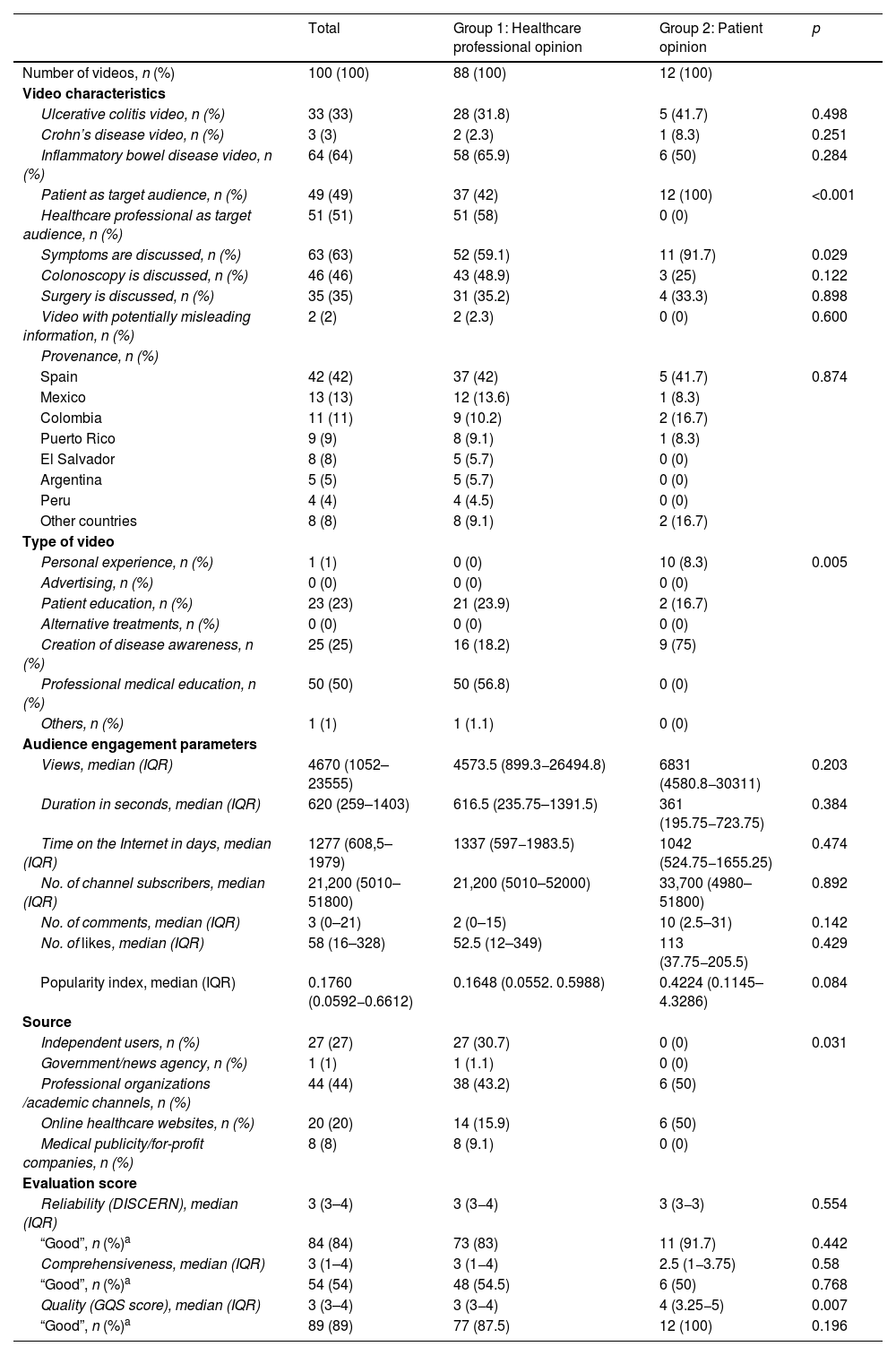

All the videos included were considered useful for patients. Only two videos contained imprecise information, at some point, that could be considered misleading for the patient. Eighty-eight videos included information created by healthcare professionals and their viewpoints (group 1) and 12 included patient opinions (group 2). Upon comparing the two groups (Table 1), patients were the target audience for all the videos created by patients, but they were the target audience for only 42% of the videos created by healthcare professionals (p < 0.001).

Characteristics of the YouTube® videos in Spanish on inflammatory bowel diseases by opinion group.

| Total | Group 1: Healthcare professional opinion | Group 2: Patient opinion | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of videos, n (%) | 100 (100) | 88 (100) | 12 (100) | |

| Video characteristics | ||||

| Ulcerative colitis video, n (%) | 33 (33) | 28 (31.8) | 5 (41.7) | 0.498 |

| Crohn’s disease video, n (%) | 3 (3) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (8.3) | 0.251 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease video, n (%) | 64 (64) | 58 (65.9) | 6 (50) | 0.284 |

| Patient as target audience, n (%) | 49 (49) | 37 (42) | 12 (100) | <0.001 |

| Healthcare professional as target audience, n (%) | 51 (51) | 51 (58) | 0 (0) | |

| Symptoms are discussed, n (%) | 63 (63) | 52 (59.1) | 11 (91.7) | 0.029 |

| Colonoscopy is discussed, n (%) | 46 (46) | 43 (48.9) | 3 (25) | 0.122 |

| Surgery is discussed, n (%) | 35 (35) | 31 (35.2) | 4 (33.3) | 0.898 |

| Video with potentially misleading information, n (%) | 2 (2) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0.600 |

| Provenance, n (%) | ||||

| Spain | 42 (42) | 37 (42) | 5 (41.7) | 0.874 |

| Mexico | 13 (13) | 12 (13.6) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Colombia | 11 (11) | 9 (10.2) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Puerto Rico | 9 (9) | 8 (9.1) | 1 (8.3) | |

| El Salvador | 8 (8) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Argentina | 5 (5) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Peru | 4 (4) | 4 (4.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Other countries | 8 (8) | 8 (9.1) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Type of video | ||||

| Personal experience, n (%) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 10 (8.3) | 0.005 |

| Advertising, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Patient education, n (%) | 23 (23) | 21 (23.9) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Alternative treatments, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Creation of disease awareness, n (%) | 25 (25) | 16 (18.2) | 9 (75) | |

| Professional medical education, n (%) | 50 (50) | 50 (56.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Others, n (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Audience engagement parameters | ||||

| Views, median (IQR) | 4670 (1052–23555) | 4573.5 (899.3−26494.8) | 6831 (4580.8−30311) | 0.203 |

| Duration in seconds, median (IQR) | 620 (259–1403) | 616.5 (235.75–1391.5) | 361 (195.75−723.75) | 0.384 |

| Time on the Internet in days, median (IQR) | 1277 (608,5–1979) | 1337 (597−1983.5) | 1042 (524.75−1655.25) | 0.474 |

| No. of channel subscribers, median (IQR) | 21,200 (5010–51800) | 21,200 (5010–52000) | 33,700 (4980–51800) | 0.892 |

| No. of comments, median (IQR) | 3 (0–21) | 2 (0–15) | 10 (2.5–31) | 0.142 |

| No. of likes, median (IQR) | 58 (16–328) | 52.5 (12–349) | 113 (37.75−205.5) | 0.429 |

| Popularity index, median (IQR) | 0.1760 (0.0592−0.6612) | 0.1648 (0.0552. 0.5988) | 0.4224 (0.1145–4.3286) | 0.084 |

| Source | ||||

| Independent users, n (%) | 27 (27) | 27 (30.7) | 0 (0) | 0.031 |

| Government/news agency, n (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Professional organizations /academic channels, n (%) | 44 (44) | 38 (43.2) | 6 (50) | |

| Online healthcare websites, n (%) | 20 (20) | 14 (15.9) | 6 (50) | |

| Medical publicity/for-profit companies, n (%) | 8 (8) | 8 (9.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Evaluation score | ||||

| Reliability (DISCERN), median (IQR) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3−4) | 3 (3−3) | 0.554 |

| “Good”, n (%)a | 84 (84) | 73 (83) | 11 (91.7) | 0.442 |

| Comprehensiveness, median (IQR) | 3 (1–4) | 3 (1−4) | 2.5 (1−3.75) | 0.58 |

| “Good”, n (%)a | 54 (54) | 48 (54.5) | 6 (50) | 0.768 |

| Quality (GQS score), median (IQR) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3−4) | 4 (3.25−5) | 0.007 |

| “Good”, n (%)a | 89 (89) | 77 (87.5) | 12 (100) | 0.196 |

GQS: Global Quality Score; IQR: interquartile range.

The majority of the videos were made in Spain (42%), followed by Mexico (13%) and Colombia (11%) (Table 1). There was greater discussion about disease symptoms (91.7% vs 59.1%, p = 0.029) and a more frequent focus on creating disease awareness (18.2% vs 75%) or describing personal experiences (0% vs 8.3%) in the group 2 videos, whereas the focus on professional medical education was more frequent (56.8% vs 0%) (p < 0.005) in the group 1 videos.

There was no statistically significant difference in the audience engagement parameters, but the group 2 videos showed a trend toward a higher popularity index (0.1648 vs 0.4224, p = 0.084). There were no differences in the median reliability scores (DISCERN 3 vs 3, p = 0.554) or the comprehensiveness scores (3 vs 2.5, p = 0.768) between the two groups, but there was greater quality in the group 2 videos (GQS 3 vs 4, p = 0.007).

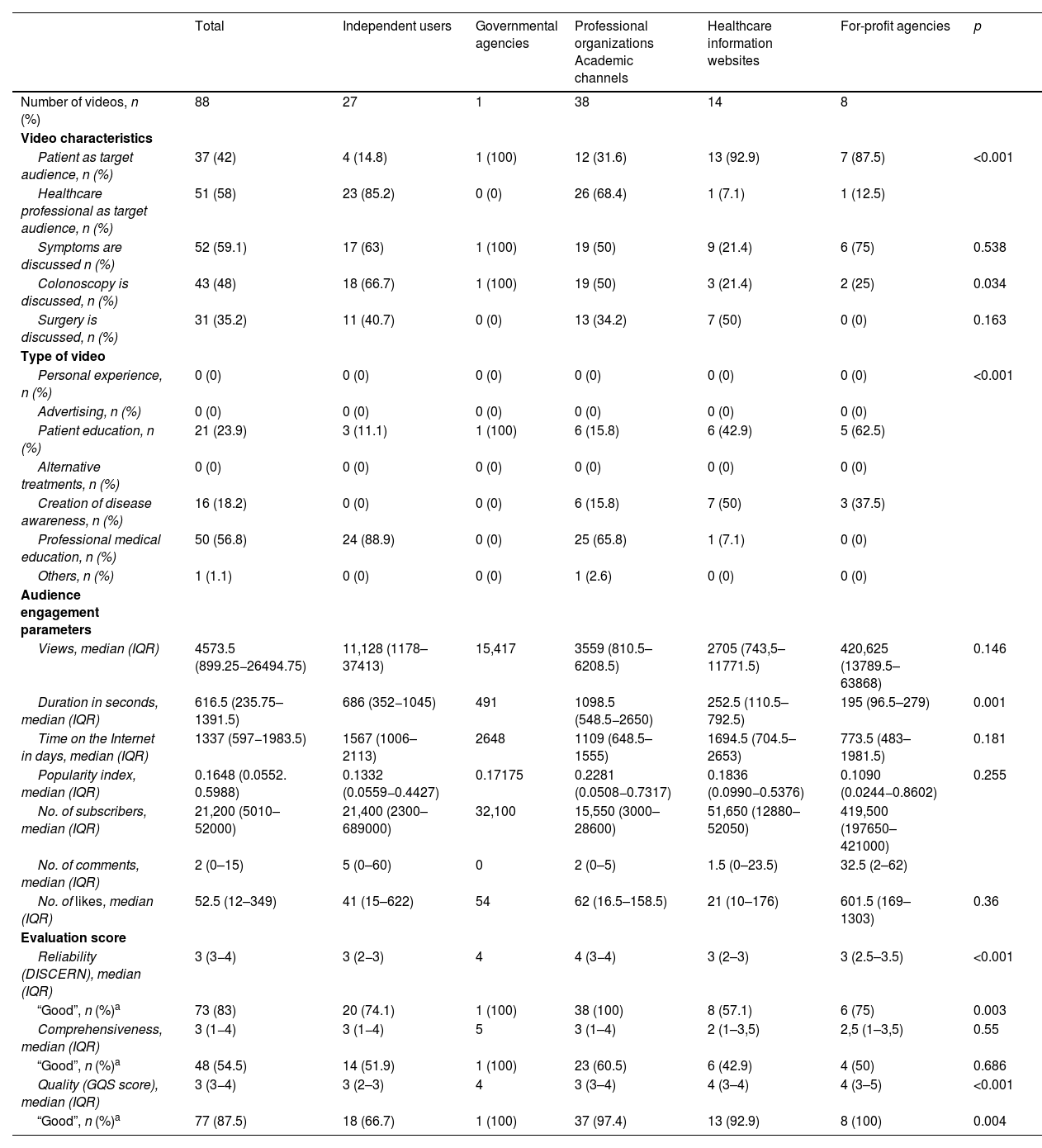

SourcesRegarding source evaluation (Table 2), the healthcare websites (87.5%) and the for-profit agency websites (92.9%) more frequently created videos aimed at patients, whereas healthcare personnel were the target audience for the videos created by independent users (85.2%) and professional organizations (68.4%).

Characteristics of the YouTube® videos in Spanish on inflammatory bowel disease by source.

| Total | Independent users | Governmental agencies | Professional organizations Academic channels | Healthcare information websites | For-profit agencies | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of videos, n (%) | 88 | 27 | 1 | 38 | 14 | 8 | |

| Video characteristics | |||||||

| Patient as target audience, n (%) | 37 (42) | 4 (14.8) | 1 (100) | 12 (31.6) | 13 (92.9) | 7 (87.5) | <0.001 |

| Healthcare professional as target audience, n (%) | 51 (58) | 23 (85.2) | 0 (0) | 26 (68.4) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Symptoms are discussed n (%) | 52 (59.1) | 17 (63) | 1 (100) | 19 (50) | 9 (21.4) | 6 (75) | 0.538 |

| Colonoscopy is discussed, n (%) | 43 (48) | 18 (66.7) | 1 (100) | 19 (50) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (25) | 0.034 |

| Surgery is discussed, n (%) | 31 (35.2) | 11 (40.7) | 0 (0) | 13 (34.2) | 7 (50) | 0 (0) | 0.163 |

| Type of video | |||||||

| Personal experience, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Advertising, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Patient education, n (%) | 21 (23.9) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (100) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (42.9) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Alternative treatments, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Creation of disease awareness, n (%) | 16 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (15.8) | 7 (50) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Professional medical education, n (%) | 50 (56.8) | 24 (88.9) | 0 (0) | 25 (65.8) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Others, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Audience engagement parameters | |||||||

| Views, median (IQR) | 4573.5 (899.25−26494.75) | 11,128 (1178–37413) | 15,417 | 3559 (810.5–6208.5) | 2705 (743,5–11771.5) | 420,625 (13789.5–63868) | 0.146 |

| Duration in seconds, median (IQR) | 616.5 (235.75–1391.5) | 686 (352−1045) | 491 | 1098.5 (548.5−2650) | 252.5 (110.5–792.5) | 195 (96.5–279) | 0.001 |

| Time on the Internet in days, median (IQR) | 1337 (597−1983.5) | 1567 (1006–2113) | 2648 | 1109 (648.5–1555) | 1694.5 (704.5–2653) | 773.5 (483–1981.5) | 0.181 |

| Popularity index, median (IQR) | 0.1648 (0.0552. 0.5988) | 0.1332 (0.0559−0.4427) | 0.17175 | 0.2281 (0.0508−0.7317) | 0.1836 (0.0990−0.5376) | 0.1090 (0.0244−0.8602) | 0.255 |

| No. of subscribers, median (IQR) | 21,200 (5010–52000) | 21,400 (2300–689000) | 32,100 | 15,550 (3000–28600) | 51,650 (12880–52050) | 419,500 (197650–421000) | |

| No. of comments, median (IQR) | 2 (0–15) | 5 (0–60) | 0 | 2 (0–5) | 1.5 (0–23.5) | 32.5 (2–62) | |

| No. of likes, median (IQR) | 52.5 (12–349) | 41 (15–622) | 54 | 62 (16.5–158.5) | 21 (10–176) | 601.5 (169–1303) | 0.36 |

| Evaluation score | |||||||

| Reliability (DISCERN), median (IQR) | 3 (3−4) | 3 (2−3) | 4 | 4 (3−4) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2.5–3.5) | <0.001 |

| “Good”, n (%)a | 73 (83) | 20 (74.1) | 1 (100) | 38 (100) | 8 (57.1) | 6 (75) | 0.003 |

| Comprehensiveness, median (IQR) | 3 (1−4) | 3 (1−4) | 5 | 3 (1–4) | 2 (1–3,5) | 2,5 (1–3,5) | 0.55 |

| “Good”, n (%)a | 48 (54.5) | 14 (51.9) | 1 (100) | 23 (60.5) | 6 (42.9) | 4 (50) | 0.686 |

| Quality (GQS score), median (IQR) | 3 (3−4) | 3 (2–3) | 4 | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

| “Good”, n (%)a | 77 (87.5) | 18 (66.7) | 1 (100) | 37 (97.4) | 13 (92.9) | 8 (100) | 0.004 |

GQS: Global Quality Score; IQR: interquartile range.

The median of duration was lower in the videos created by for-profit agencies (195 s; IQR 96.5–279) and healthcare information websites (252 s; IQR 110.5–792.5) than in those created by professional organizations (1098.5 s; IQR: 548.5−2650) (p = 0.001). There were no differences in the number of views, comments, or likes, or in the popularity indexes.

Lastly, reliability was greater for the videos created by professional organizations (DISCERN 4; IQR 3−4), compared with those created by healthcare information websites and for-profit agencies (DISCERN 3) (p < 0.001). Comprehensiveness scores were similar, unlike the overall quality evaluation, which was higher for the healthcare information website and for-profit agency website sources (GQS 3 vs 4, p < 0.001).

DiscussionThe present study is the first to evaluate YouTube® videos available in Spanish as a source of information for patients with IBD. Our results suggest that the majority of videos have good reliability, comprehensiveness, and quality. In addition, patient-targeted information is more frequently created by healthcare information websites and for-profit agencies, whereas healthcare personnel-targeted information is produced by academic organizations. Lastly, our data suggest that the overall quality of the videos that present patient opinions and those that are created by healthcare information websites and for-profit agencies may be superior.

The quality of information about IBD on YouTube® appears to be different, when comparing videos in Spanish with those in English. A study conducted in 2012 that evaluated videos in English concluded that YouTube® was a poor educational resource for patients, given that only one out of 45 videos on CD had a 5/5 score on the GQS scale and two of the 29 videos on UC had a GQS score of 4/5.10 Nevertheless, we found that the majority of the videos evaluated in our study were useful and reliable for patients. The differences described between the two studies, with respect to overall quality, could be secondary to a larger number of videos not aimed at a medical target audience (92.5%), a difference in the populations studied (the majority of the videos in English were from the United States [88.9%]), or to changes in current YouTube® policies for managing disinformation, which were revised during the COVID-19 pandemic and favor a selection of videos with no misleading content.20,21 In addition, we found that only 2% of the videos contained imprecise information that could be considered misleading for patients, a percentage lower than those reported for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), in which 16.4% of the videos were classified as misleading,22,23 rheumatoid arthritis (30.4%)17, or Sjögren’s syndrome (8.6%).24 Keeping in mind that many of those studies were conducted before 2015, they would likely have different results if they were repeated, given the changes in YouTube® policies. Nevertheless, it is hypothesized that videos on less prevalent chronic diseases may be associated with fewer misleading videos, exemplified by the study conducted on videos in Spanish on LES,23 developed in 2022, that found less than 5% of videos contained false information. Lastly, the prevalence of the disease in Spanish-speaking countries, could directly affect the amount of IBD-related information available on SMNs. IBD has a higher prevalence in countries with a larger English-speaking population, thus the probability of finding more false information could increase, given the larger affected population.

Approximately half of the videos on IBD are patient-directed. Taking into account that 75% of the patients with IBD search the Internet for specific information on their disease,9 the fact that patients can access good quality information is relevant. The present study shows that the majority of videos about IBD on YouTube® had good reliability, comprehensiveness, and overall quality. Thus, YouTube® can be a useful source of information for patients. Other studies have shown similar results for other diseases, such as osteoporosis,13 gout,25 SLE,22,23 rheumatoid arthritis,17 Sjögren’s syndrome,24 and spondylolisthesis.26 However, the fact that the majority of content aimed at patients with IBD is created by healthcare information websites and for-profit agencies is striking. Even though the information available in Spanish is useful and accurate for patients, those results are a call to action for professional and academic organizations. Recognizing the importance of self-sufficiency in the management of patients with a chronic disease and following the clinical practice guidelines regarding the consensual decisions with respect to the treatment of patients with IBD, SMNs are a growing opportunity for providing quality information evaluated by academic peers.

When comparing the audience engagement parameters, there were no differences in comprehensiveness or quality of the videos on IBD. Strikingly, even the shorter videos (between 3 and 4 min), for example, those produced by the healthcare information websites or the for-profit agencies, were not less comprehensive or of less quality, suggesting that patient-directed videos could be shorter without reducing quality. Such a situation could improve the acceptance of information. In addition, a video focusing on a specific problem (e.g., mental health) could be highly useful, despite being less comprehensive and having a shorter duration.

We believe the greater quality of the videos that contained patient opinions could be related to the effects of the presence of a larger quantity of information on emotional support, self-esteem, support networks, and IBD-related information.5,27 However, the fact that the available evidence suggests that videos focused on patient narratives are not effective in terms of better decision-making by the patients should be noted.28 Therefore, the creation of information endorsed by academic peers is of great importance.

Despite the fact that 80% of the videos on YouTube® are good quality, there were variations, according to the source. We found that the higher quality videos were those whose sources were healthcare information websites or for-profit agencies. Previous studies on rheumatic diseases have shown higher scores for videos with sources related to professional organizations.13,22,25 The higher score obtained by the healthcare information websites could be secondary to greater patient participation in that source (42.8%), as well as to better visual presentation of the videos. Thus, the results found in videos created by healthcare information websites and for-profit agencies could serve as an example for improving patient-directed videos.

Lastly, we found differences between reliability and quality, in the comparison of healthcare professional opinion and patient opinion, as well as in the comparison of video sources. Even though there was greater reliability, with respect to the videos created by healthcare professionals and professional organizations, quality was better in the patient opinion, healthcare information website, and for-profit agency videos. That finding does not concur with results from other authors. For example, in a study that evaluated the quality and reliability of information about spondylolisthesis on YouTube®, there was a good correlation between the DISCERN and GQS scores (70%).26 Those differences could be associated with different evaluator perception, with respect to whether more precise information is preferrable to more “useful” information, according to patient needs.5

The main limitation of our study was associated with the element of subjectivity in the evaluation, despite the use of standardized instruments. The peer-reviewed evaluation of the videos and the search for consensus regarding their evaluations reduced the impact of said limitation. Keeping in mind that the evaluation of healthcare information reported on SMNs is a growing area of research,29 the optimization and development of better tools for assessing the reliability, comprehensiveness, and quality of information on SMNs is expected in the future. An additional limitation was the fact that only the information available on YouTube® was assessed, possibly signifying that the results cannot be extrapolated onto other social media networks.11 Finally, videos that could be present on specialized IBD websites and that are not on YouTube® were not evaluated. Nevertheless, recent evidence on other chronic diseases suggests that patients do not tend to consult websites as a source of information.30

In conclusion, the majority of videos about IBD in Spanish on YouTube® have good reliability, comprehensiveness, and quality, regardless of whether they are the opinion of a healthcare professional, the opinion of a patient with IBD, and no matter their source. In addition, we found that patient opinion, healthcare information website, and for-profit agency videos, were of higher quality. Professional organizations should adopt an active role in creating quality educational content for patients with IBD.

Financial disclosureNo specific grants were received from public sector agencies, the business sector, or non-profit organizations in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

See related content in DOI: 10.1016/j.rgmxen.2023.05.007, Bandera Quijano, J. YouTube® as a source of information for patients with gastrointestinal disease, Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2024;173–175.