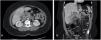

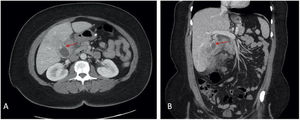

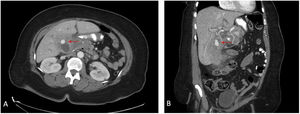

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysms are rarely seen and can easily be confused with cholelithiasis, as well as missed on imaging. Ultrasound is often performed first, but computed tomography (CT) provides the best characterization. While angiography with staged cholecystectomy is the procedure of choice, upfront surgical intervention can also be safely done. A 52-year-old woman presented with recurrent right upper quadrant pain and nausea and had a CT scan that revealed extensive gallbladder wall thickening with pericholecystic stranding, fluid collections, and an intraluminal hyperdensity that was considered to be cholelithiasis (Fig. 1). On hospital day five, the patient developed worsening symptoms and a repeat CT scan demonstrated an increase in the hyperdense intraluminal focus and hyperdense material in the bile ducts (Fig. 2). Those findings indicated an enlarging pseudoaneurysm with bleeding into the bile ducts. Due to concern for acute bleeding, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy. Extensive inflammation was encountered and the pseudoaneurysm was identified and removed (Fig. 3). The bleeding vessel was ligated, and a partial cholecystectomy was performed.

The authors declare that no experiments were conducted on humans or animals for the present article, that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data, and that they have preserved patient confidentiality and anonymity at all times. Informed consent was requested from the patient for the surgical intervention and for utilization of images and clinical data for scientific purposes.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Tagerman D, Romero-Velez G, Bellemare S. Pseudoaneurisma de la arteria cística. Rev Gastroenterol Méx. 2022;87:489–490.