Iron-deficiency anemia can be caused by occult bleeding of the digestive tract secondary to diverse lesions of different prevalence and severity.1 Among them are those of vascular origin, such as blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS), also known as Bean syndrome, initially described by Gascoyen in 1860. In 1958 Bean associated the lesions of the skin with those of the gastrointestinal tract, and since then the syndrome bears his name.2

A 45-year-old woman was referred to our hospital center to study her iron-deficiency anemia. Her personal and family medical histories were unremarkable. Hematocrit was 27%, hemoglobin 9.0g/dl, white blood cell count 7,500/mm3, serum iron 60μg/dl, coagulogram was normal, and serology for celiac disease was negative. The medical history was taken and the patient did not complain of symptoms or findings that could be linked to anemia or gastrointestinal bleeding. The physical examination revealed the presence of vascular lesions on the feet and abdomen (Fig. 1).

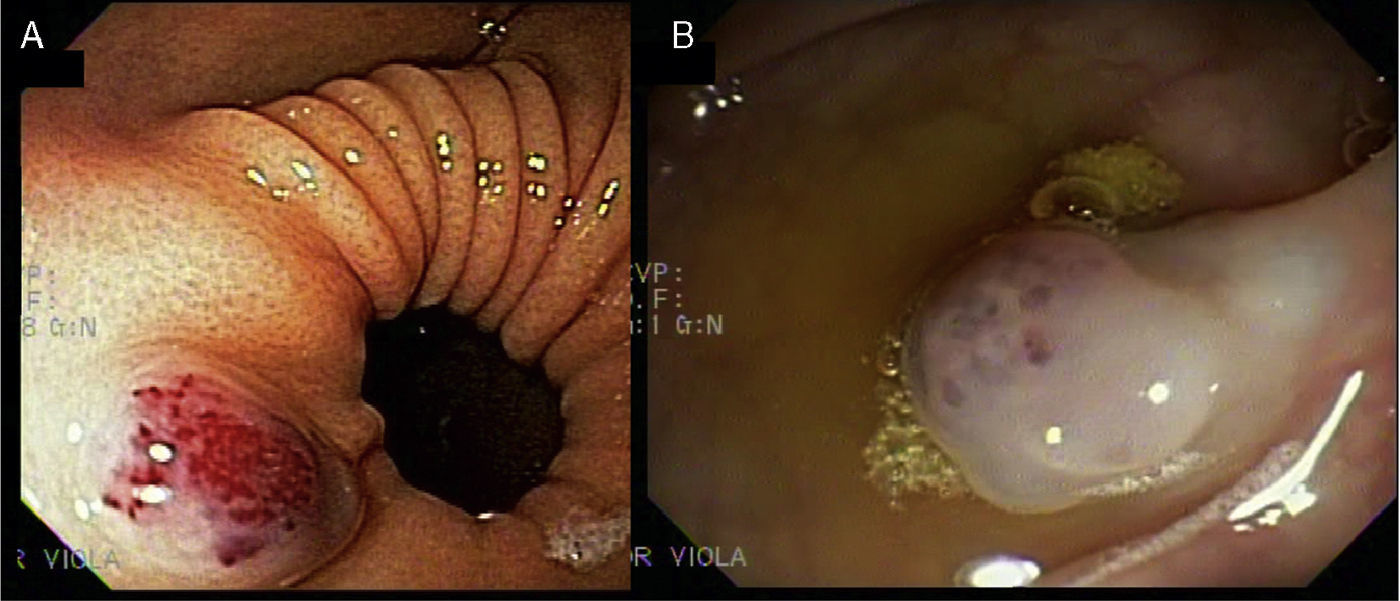

The lesions were round, bluish, rubbery, and nonpainful and had a diameter that varied from 1 to 3cm. One of the lesions deformed a foot. Upper and lower gastrointestinal video endoscopy was performed, displaying a lesion on the anterior surface of the pyloric antrum that measured 2cm in diameter; it was bluish and rounded and had a soft consistency (Fig. 2A).

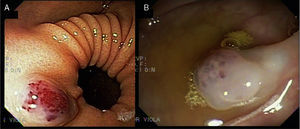

Three similar lesions were observed on the colon (Fig. 2B). There were no signs of bleeding and the abdominal ultrasound was normal. Given the cutaneous and gastrointestinal lesions, BRBNS was diagnosed and it was assumed to be responsible for the anemia, once urologic and gynecologic bleeding was ruled out. The patient agreed with the recommendation not to evaluate the small bowel, given that she did not present with symptoms. Oral iron replacement was begun and her anemia was corrected. The patient is presently in stable condition.

BRBNS is a rare syndrome that combines the presence of cutaneous and visceral venous malformations that are typically small, circumscribed, and multifocal. Even though the disease appears sporadically in the majority of reported cases, some have a dominant autosomal component related to a mutation of chromosome 9p.3 The epidemiology and natural history of BRBNS is not well known. Due to its rareness, emphasized by all authors, there are no figures related to prevalence, the incidence of bleeding, or mortality. There are thought to be about 150 communicated cases worldwide.4 The digestive tract is frequently compromised by multiple papilliform bluish lesions. The small bowel is the most common location, followed by the colon, but there can also be lesions at the mouth of the anus.3 In general, they are present from birth and their appearance in adulthood is less likely.2,3 The majority of the cases manifest as occult bleeding. In the largest case series to date, Fishman et al. conducted their study on 32 patients from a referral center; 22 of them presented with minimal bleeding and 10 had severe bleeding.2 Rare complications such as intussusception, volvulus, infarct, and obstruction have been reported.5 The cutaneous lesions are generally small, measuring less than 2cm; their color ranges from blue to purple and they rarely bleed spontaneously. Other uncommon locations are: the brain, eyes, oral cavity, thyroid, lungs, pericardium, pleura, spleen, liver, kidneys, bladder, and muscle and skeletal system.4,6 The extradigestive and extracutaneous lesions can produce epistaxis, hemoptysis, hematuria, or metrorrhagia. There can be joint pain when the muscle and skeletal system is involved.7 Physical examination can reveal skin lesions or joint deformities. From the histopathologic perspective, cutaneous lesions show vessels with ectasia that are filled with blood and covered by a single layer of endothelial cells surrounded by thin connective tissue.7 Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies reveal gastrointestinal lesions and the evaluation can be completed with capsule endoscopy or enhanced radiologic studies for detecting small bowel lesions.8 Ultrasound, nuclear magnetic resonance, computed tomography, and angiography can identify visceral involvement in other locations.3 The morbidity and mortality of BRBNS depends on the extent of visceral involvement and treatment is contingent on the magnitude of the symptoms.7 More severe cases of anemia can require blood transfusions. Different endoscopic treatments have been described, such as resection, sclerotherapy, band ligature, and coagulation. Although reduced bleeding has been reported, recurrence appears to be habitual.3,7 The following have been used experimentally: corticoids, interferon, octreotide, antifibrinolytics, gamma globulin, and vincristine. The results are disparate and do not provide conclusive evidence.9 The majority of authors recommend conservative treatment, reserving endoscopic or surgical therapy for severe hemorrhages or for symptoms of occlusion and perforation.2

In conclusion, we underline the importance of an integral examination of the patient in order to detect the cutaneous lesions that lead to the diagnosis. We also point out the necessity of performing endoscopic studies for identifying the source of bleeding. We suggest a conservative therapeutic approach to the degree that the mildness of the anemia and the response to iron replacement permit.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Wonaga A, Fernández JL, Barsanti A, Viola LA. Una causa infrecuente de anemia ferropénica: blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2014;79:151–152.