There are few studies that compare polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 and magnesium hydroxide (MH), as long-term treatment of functional constipation (FC) in children, and they do not include infants as young as 6 months of age. Our aim was to determine the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of PEG vs MH in FC, in the long term, in pediatric patients.

MethodsAn open-label, parallel, controlled clinical trial was conducted on patients from 6 months to 18 years of age, diagnosed with FC, that were randomly assigned to receive PEG 3350 or MH for 12 months. Success was defined as: ≥ 3 bowel movements/week, with no fecal incontinence, fecal impaction, abdominal pain, or the need for another laxative. We compared adverse events and acceptability, measured as rejected doses of the laxative during the study, in each group and subgroup.

ResultsEighty-three patients with FC were included. There were no differences in success between groups (40/41 PEG vs 40/42 MH, p = 0.616). There were no differences in acceptability between groups, but a statistically significant higher number of patients rejected MH in the subgroups > 4 to 12 years and > 12 to 18 years of age (P = .037 and P = .020, respectively). There were no differences regarding adverse events between the two groups and no severe clinical or biochemical adverse events were registered.

ConclusionsThe two laxatives were equally effective and safe for treating FC in children from 0.5 to 18 years of age. Acceptance was better for PEG 3350 than for MH in patients above 4 years of age. MH can be considered first-line treatment for FC in children under 4 years of age.

Existen pocos estudios comparativos entre polietilenglicol (PEG) 3350 e hidróxido de magnesio (HM) para tratar el estreñimiento funcional (EF) a largo plazo en niños, y no incluyen lactantes desde 6 meses. El objetivo fue determinar la eficacia, la seguridad y la aceptabilidad de PEG vs HM en el EF a largo plazo en pacientes pediátricos.

MétodosEnsayo clínico controlado, paralelo, abierto, en pacientes de 6 meses a 18 años con diagnóstico de EF asignados aleatoriamente a PEG 3350 o HM durante 12 meses. Se definió éxito: ≥ 3 evacuaciones/semana, sin incontinencia fecal, impactación fecal, dolor abdominal o necesidad de otro laxante. Se compararon eventos adversos, así como la aceptabilidad, medida como dosis rechazadas del laxante durante el estudio en cada grupo y subgrupo.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 83 pacientes con EF, sin que presentaran diferencias en éxito entre ambos grupos (40/41 PEG vs 40/42 HM, p = 0.616). No hubo diferencias en aceptabilidad entre ambos grupos, pero un número significativamente mayor de pacientes rechazó la leche de magnesia en los subgrupos de > 4 a 12 años y de > 12 a 18 años (p = 0.037 y p = 0.020, respectivamente). No hubo diferencias de eventos adversos entre ambos grupos y no se registraron eventos adversos clínicos ni bioquímicos graves.

ConclusionesAmbos laxantes fueron igualmente efectivos y seguros para tratar el EF en niños de 0.5 a 18 años. El PEG 3350 fue mejor aceptado que el HM por los pacientes mayores de 4 años. El HM puede ser considerado como tratamiento de primera línea para EF en niños menores de 4 años.

Constipation is a common problem in the pediatric population. It is estimated to account for 3% of pediatric consultations and 25% of pediatric gastroenterology consultations.1,2 Children may present with it from the early stages of life, with a prevalence of 2.9% in the first year of life and 10.1% in the second year.3 Many disorders can cause constipation in children, but functional constipation (FC) accounts for 97% of the cases.3 Much less frequently, constipation is the result of systemic conditions or anatomic alterations, which can be ruled out through a complete and detailed clinical evaluation. Even though 25% of the cases of FC improve with simple measures, such as family education and changes in dietary habits, a favorable response is obtained in 95% of the patients by the combination of diet and laxatives.3 As first-line treatment, osmotic laxatives are recommended, for treating FC in children.4

Magnesium hydroxide (MH), better known as milk of magnesia, is an osmotic laxative that reduces colonic transit time and increases osmolarity. It is widely used in Mexico, given that it is accessible and economic. Its side effects gain much importance in patients with kidney failure because they increase the risk for hypermagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, or hypocalcemia; other side effects are dehydration, incontinence, and abdominal cramps. Its poor palatability is the reason many children refuse to take it for prolonged periods of time.5,6

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a chemically inert polymer in powdered form. It is insipid, odorless, and colorless and can be mixed in juice, plain water, and artificially flavored water, as well as in infant formulas.7 It is not degraded by bacteria and its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract is minimal, making it an excellent osmotic agent, increasing the water content of stool.8,9 PEG without electrolytes has been shown to be useful for treating constipation in pediatric patients,7,10–21 as well as being safe and more efficacious than placebo for the short-term treatment of children with FC.22 However, there are few studies that compare PEG and MH, with respect to effectiveness, safety, and acceptance.19,20

The latest management guidelines suggested by the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) place PEG as a first-line medication for FC maintenance therapy, followed by lactulose, if PEG is not available; MH, mineral oil, and stimulating laxatives are considered added or second-line treatment.4

At present, there is only one randomized study that compares the effectiveness, safety, and acceptability of the 12-month treatment of PEG 3350 without electrolytes and MH, in children ≥ 4 years of age with FC and encopresis.19 Comparative studies on other laxatives that have included younger patients20,21 have a maximum follow-up period of 6 months, and only one of them evaluated safety.20 Given that FC is also a problem in younger children3 that can require longer treatment, we believe it is useful to compare the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of PEG 3350 without electrolytes and MH, for the long-term (12 months) treatment of FC, with or without encopresis in children from 6 months to 18 years of age. Our aim was to determine the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of PEG 3350 without electrolytes vs MH, in the long term, in pediatric patients.

Material and methodsStudy designAn open-label, randomized, parallel-group controlled clinical trial was conducted, within the time frame of July 2007 and July 2015, at the gastroenterology outpatient department of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez.

Study populationThe study population was made up of outpatients seen at a tertiary care hospital in Mexico. After the parents gave their informed consent and the patients above the age of 7 years signed the statements of informed consent, patients from 6 months to 18 years of age were enrolled in the study. The patients had not taken either of the study medications for at least one month and they met the Rome III diagnostic criteria for FC:23,24

- a)

From infancy to 4 years of age: the presence, for at least one month, of two or more of the following manifestations:

- 1)

≤ 2 bowel movements per week.

- 2)

≥ 1 episode per week of encopresis, after having achieved anal sphincter control.

- 3)

A history of excessive fecal retention.

- 4)

A history of hard or painful bowel movements.

- 5)

The presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum.

- 6)

A history of large-diameter bowel movements that may clog the toilet.

- 1)

- b)

Children ≥ 4 years of age: the presence at least once a week for ≥ 2 months before diagnosis, of two or more of the following manifestations:

- 1)

≤ 2 bowel movements in the toilet per week.

- 2)

≥ 1 episode per week of encopresis, after having achieved anal sphincter control.

- 3)

A history of retentive posturing or excessive voluntary stool retention.

- 4)

A history of hard or painful bowel movements.

- 5)

The presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum.

- 6)

A history of large-diameter bowel movements that may clog the toilet.

- 1)

The exclusion criteria were patients with a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome, secondary constipation, abdominal surgery, an anatomic abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract, or a comorbidity that could affect treatment results. Those criteria were maintained throughout the study, with no modifications.

Sample sizeSample size for comparing two proportions was calculated using the STATA 9.2 (College Station, Texas 77845 USA) program. Taking into account an α of 0.05 (two-tailed test) and a power of 90%, with a p1 = 0.05, p2 = 0.35, and N2/N1 = 1.00, produced 42 patients per treatment group. After calculating a 10% loss of patients, the final number per group was 46.

RandomizationAt the initial visit, the patient’s suitability to be enrolled in the study was corroborated. If fecal impaction was detected, rectal disimpaction was carried out, utilizing soap suds enemas. Patients were then assigned to a treatment group, using the randomized block method, to have balanced groups in three different age subgroups (6 months to 4 years, > 4 years to 12 years, and > 12 years to 18 years). A table of randomized numbers created with the Excel program by a third party that did not participate in patient enrollment was utilized. The intervention maneuver could not be blinded due to the difference in the physical characteristics and presentation of the two interventions. The data were analyzed by an independent researcher that had no direct contact with the patients.

Age subgroupsThe decision was made to have different age subgroups, to evaluate whether patient age influenced the efficacy, safety, and acceptance of each of the laxatives, especially for MH, given its poor palatability. Taking into account that doses would be weight-based, older patients would ingest a larger volume of MH, potentially making its acceptance more difficult. Therefore, three subgroups were established. The first subgroup corresponded to the ages of 6 months to 4 years, according to the Rome III criteria for the classification of FC; the second subgroup was from 4 to 12 years of age; and the third subgroup included only adolescents. Adolescents are generally more difficult to treat due to low treatment adherence, especially if treatment is long, as well as to the fact that they are the group that has to take the higher doses of laxative, given their weight.

InterventionsGroup 1PEG 3350 (Contumax®, Asofarma de México, S.A. de C.V., Mexico), 0.7 g/kg/day23 dissolved in plain water, flavored water, juice, or milk, at one to three doses per day. The dose was increased by 5 g, dissolved in two oz of liquid, every third day, until achieving one to three bowel movements of soft consistency per day. The dose was decreased by the same proportion if bowel movements were liquid or there were more than three per day. Once the goal was achieved, the dose was maintained.

Group 2MH (Normex®, Química y Farmacia S.A. de C.V., Mexico), 2 ml/kg/day alone or dissolved in juice, blended milk drinks, chocolate milk, or other flavored drinks, at one to three doses per day. The dose was increased by 5 ml every third day until achieving one to three bowel movements of soft consistency per day. The dose was decreased by the same proportion if bowel movements were liquid or there were more than three per day. Once the goal was achieved, the dose was maintained.

Treatment instructionsThe treatment goal, which was to achieve one to three daily bowel movements of soft consistency, no abdominal pain, and no fecal incontinence (FI), was verbally explained to the parents. They were told how to increase or decrease the doses of the medications to reach the goal and were given an instruction sheet containing the written indications. All patients that had anal sphincter control were instructed to sit on the toilet after each meal.

Follow-upAfter the initial visit, clinical controls were carried out at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of treatment, at which the following aspects were evaluated: bloating, palpable masses in the abdomen, pain upon abdominal palpation, fecal impaction (hard stools in the rectum or the lower abdomen), and stools in the perianal region and/or on the underwear. Blood samples of approximately 5 ml were taken for the baseline laboratory tests and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of treatment: complete blood count, ureic nitrogen, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and serum electrolytes (Na, K, Cl, Ca, P, and Mg).

Data collectionThe parents were instructed to keep a diary, during the entire study, registering:

- 1)

The daily dose of PEG (g/day) or milk of magnesia (ml/day), according to the laxative utilized.

- 2)

The number of medication doses rejected per day: the number of doses of the laxative that the patient refused to take in 24 h.

- 3)

The use of another laxative/day (yes/no): the added use of any other laxative in 24 h.

- 4)

The number of doses of the other laxative/day: the number of doses of the added laxative in 24 h.

- 5)

Enemas/day (yes/no): the use of rectal washouts in 24 h.

- 6)

The number of enemas/day: number of rectal washouts performed in 24 h.

- 7)

The number of bowel movements/day: the number of bowel movements in the toilet or diaper that the patient had in 24 h.

- 8)

Stool consistency:

- a)

Hard stool (HS), any shape, with a rock-hard consistency, very difficult to pass and impossible to press.

- b)

Soft stool (SS), any shape, soft, easy to pass, easily pressed.

- c)

Mushy stool (MS), no shape, like a thick soup.

- d)

Liquid stool (LS), an abundance of liquid, with solid residues.

- a)

- 9)

The number of episodes of retentive FI/day: the number of events of soiling underwear in 24 h, with or without hard stools in the toilet.

- 10)

The number of episodes of abdominal pain/day: the number of times the patient complained of abdominal pain in 24 h.

- 11)

Adverse events/day (yes/no): cramps, gases, abdominal pain, diarrhea, non-retentionist FI (presence of stool on underwear and liquid stools in the toilet), vomiting, dehydration, and others, with their specification.

The physicians in charge of the study kept a register of the baseline clinical data and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 of treatment; it included evidence of fecal impaction and manifestations of the autism spectrum. The data obtained from the daily registers of the patients, the consultations, and the laboratory were collected on an Excel sheet for their analysis.

EfficacyAt the end of 12 months, the following results were considered:

- 1)

Success: ≥ 3 bowel movements/week in the toilet (for the patients with anal sphincter control) or in the diaper (for patients with no anal sphincter control), with no episodes of FI, fecal impaction, or abdominal pain, and no need for another laxative.

- 2)

Partial improvement: ≥ 3 bowel movements/week in the toilet (for the patients with anal sphincter control) or in the diaper (for patients with no anal sphincter control), ≤ 2 episodes of FI per month, with no fecal impaction, no abdominal pain, and no need for another laxative.

- 3)

Failure: ≤ 2 bowel movements/week in the toilet (for the patients with anal sphincter control) or in the diaper (for patients with no anal sphincter control), with > 2 episodes of FI/month and/or ≥ 1 event of fecal impaction or the need for another laxative.

The main cutoff points of the study were: the number of patients that achieved success, the number of laxative doses rejected, and adverse events, in each treatment group and by age subgroups at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of treatment.

SecondaryThe secondary cutoff points were: laxative dose (MH: ml/kg/day; PEG: g/kg/day) needed to achieve the treatment goal; duration of treatment needed to achieve the success criteria (time in months necessary for meeting the success criteria) and the number of bowel movements, episodes of fecal impaction, and episodes of FI per week at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of treatment.

Statistical analysisA researcher blinded to the treatment assignment performed the statistical analysis. Hypothesis testing was carried out to evaluate normality in the distribution of the variables to be compared. The analytic focus of intention-to-treat was utilized. The significance of the differences between groups was determined for the primary and secondary cutoff points through the chi-square test or the Fisher’s test, for the qualitative variables, and through the Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test, for the quantitative variables. All the procedures were performed using the SPSS version 13.0 program. A two-tailed p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the comparisons.

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was approved by the Local Research and Ethics Committee of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG) (HIM/2007/032/SSA-759 and 1062) and registered in the archives of said committee. There were no protocol modifications, once the study was registered and begun. All parents of the enrolled patients gave their informed consent and patients above 7 years of age signed statements of informed consent. The authors declare that this article contains no personal information that could identify the patients.

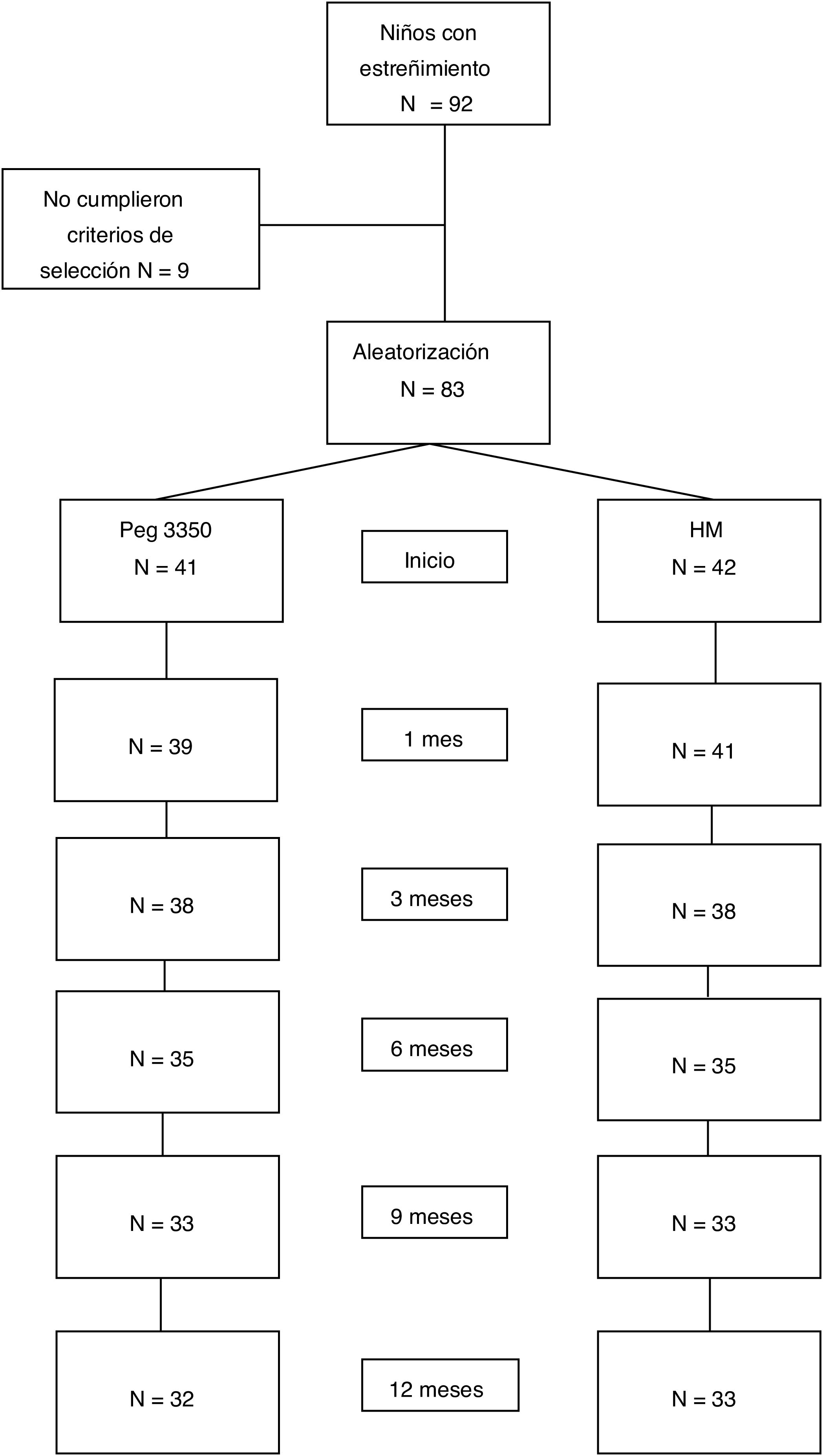

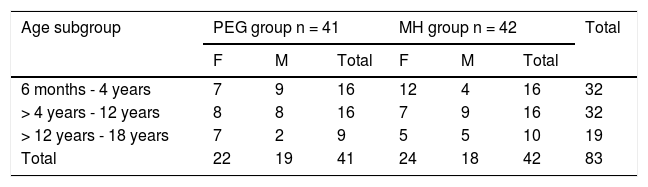

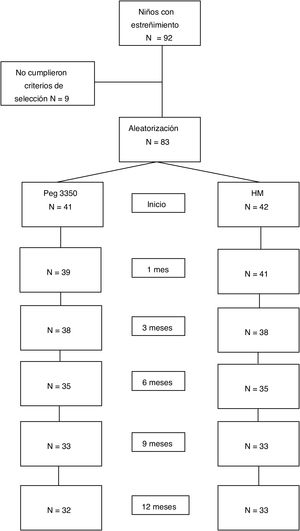

ResultsStudy populationWithin the time frame of July 2007 and July 2015, 83 patients were included in the study: 41 in the PEG group and 42 in the MH group. Fifty-three percent of the patients were females. There were no differences in the number of patients assigned to each age subgroup between the two treatment options. Table 1 shows the baseline demographic characteristics. Sixty-five patients (78%) completed the study at 12 months. Eighteen patients (9 from each group) suspended treatment before the 12 months, for different reasons: 4 due to family problems, 2 due to rejecting the medication, 2 due to intercurrent diseases, one due to psychologic problems, one due to fecal impaction, one due to diarrhea, and 7 due to no specific cause (Fig. 1).

Baseline demographic distribution.

| Age subgroup | PEG group n = 41 | MH group n = 42 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | Total | F | M | Total | ||

| 6 months - 4 years | 7 | 9 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 16 | 32 |

| > 4 years - 12 years | 8 | 8 | 16 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 32 |

| > 12 years - 18 years | 7 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 19 |

| Total | 22 | 19 | 41 | 24 | 18 | 42 | 83 |

F: female; M: male; MH: magnesium hydroxide or milk of magnesia; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

Of the 83 patients, 66 (79.5%) met the success criteria at the first month of treatment, 12 (14.5%) at 3 months, 2 (2.4%) at 6 months, and one at 9 months. Two patients (2.4%) (one from each group) were eliminated from the study. No significant differences were found in the general population, when comparing the baseline biochemical test results with those taken after the intervention. No severe adverse events were registered. The most frequent adverse events were gases, cramps, FI, and diarrhea. Twenty-nine patients (34.9%) rejected a medication dose.

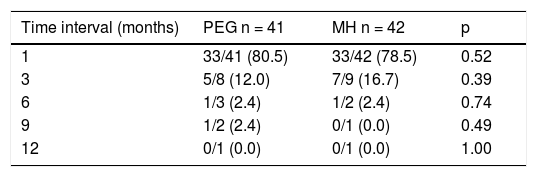

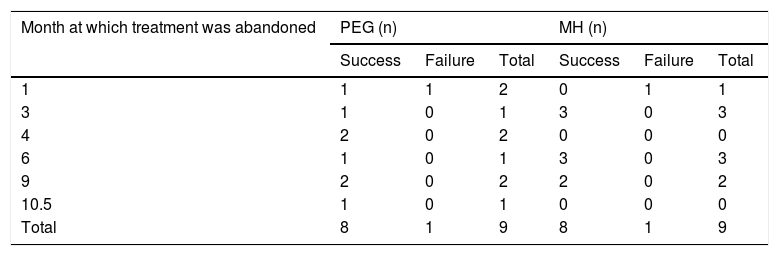

Treatment responseEfficacy40/41 patients (97.56%) in the PEG group and 40/42 patients (95.24%) in the MH group presented with success, p = 0.616. No significant differences between groups were found, with respect to the length of treatment necessary for meeting the success criteria (Table 2). Only one patient presented with partial improvement in the MH group, compared with no patients in the PEG group. Two patients had treatment failure, one from each study group. There were no differences between treatment groups, regarding the number of patients that suspended treatment before 12 months, nor with respect to the number of patients that met the success criteria or failure criteria, upon treatment suspension (Table 3). There were also no differences in the length of treatment necessary for meeting the success criteria (time in months needed to reach the success criteria) in the treatment groups or in the age subgroups at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of treatment.

Success rate comparison between treatment groups at each time interval.

| Time interval (months) | PEG n = 41 | MH n = 42 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33/41 (80.5) | 33/42 (78.5) | 0.52 |

| 3 | 5/8 (12.0) | 7/9 (16.7) | 0.39 |

| 6 | 1/3 (2.4) | 1/2 (2.4) | 0.74 |

| 9 | 1/2 (2.4) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0.49 |

| 12 | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 1.00 |

MH: magnesium hydroxide or milk of magnesia; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

Number of patients that abandoned treatment, by time interval, intervention group, and progression.

| Month at which treatment was abandoned | PEG (n) | MH (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success | Failure | Total | Success | Failure | Total | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 9 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 10.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 8 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

MH: magnesium hydroxide or milk of magnesia; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

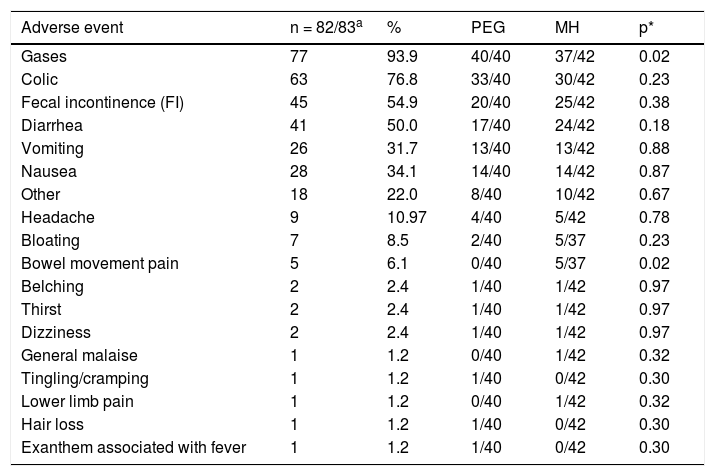

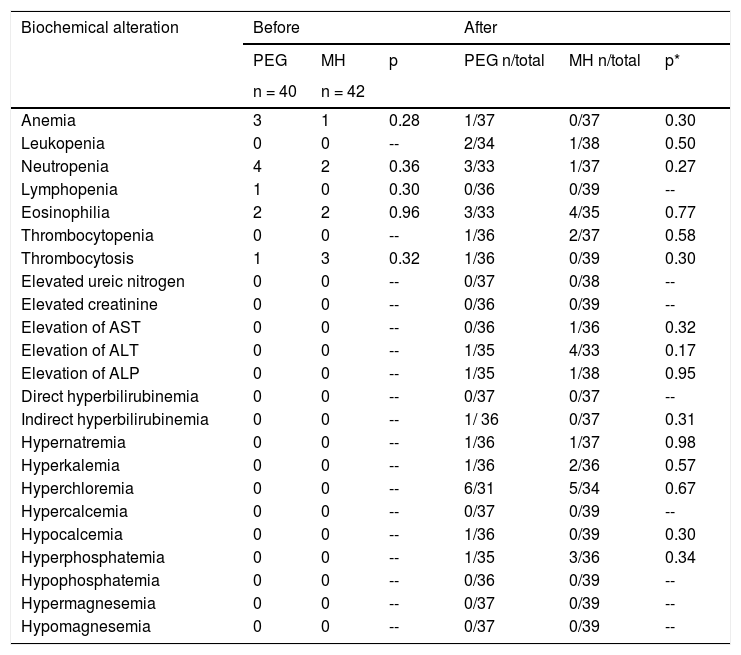

There were no severe adverse events with either of the treatment regimens in any age subgroup. A significantly higher number of patients in the PEG group presented with gases (p = 0.024) and a significantly higher number of patients in the MH group presented with painful bowel movements (p = 0.02) (Table 4). There were no significant differences by age subgroup. No significant differences were found between groups, with respect to the biochemical tests at baseline or at the end of treatment (Table 5).

Clinical adverse events. Treatment group comparison.

| Adverse event | n = 82/83a | % | PEG | MH | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gases | 77 | 93.9 | 40/40 | 37/42 | 0.02 |

| Colic | 63 | 76.8 | 33/40 | 30/42 | 0.23 |

| Fecal incontinence (FI) | 45 | 54.9 | 20/40 | 25/42 | 0.38 |

| Diarrhea | 41 | 50.0 | 17/40 | 24/42 | 0.18 |

| Vomiting | 26 | 31.7 | 13/40 | 13/42 | 0.88 |

| Nausea | 28 | 34.1 | 14/40 | 14/42 | 0.87 |

| Other | 18 | 22.0 | 8/40 | 10/42 | 0.67 |

| Headache | 9 | 10.97 | 4/40 | 5/42 | 0.78 |

| Bloating | 7 | 8.5 | 2/40 | 5/37 | 0.23 |

| Bowel movement pain | 5 | 6.1 | 0/40 | 5/37 | 0.02 |

| Belching | 2 | 2.4 | 1/40 | 1/42 | 0.97 |

| Thirst | 2 | 2.4 | 1/40 | 1/42 | 0.97 |

| Dizziness | 2 | 2.4 | 1/40 | 1/42 | 0.97 |

| General malaise | 1 | 1.2 | 0/40 | 1/42 | 0.32 |

| Tingling/cramping | 1 | 1.2 | 1/40 | 0/42 | 0.30 |

| Lower limb pain | 1 | 1.2 | 0/40 | 1/42 | 0.32 |

| Hair loss | 1 | 1.2 | 1/40 | 0/42 | 0.30 |

| Exanthem associated with fever | 1 | 1.2 | 1/40 | 0/42 | 0.30 |

MH: magnesium hydroxide or milk of magnesia; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

Biochemical test alteration between treatment groups.

| Biochemical alteration | Before | After | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG | MH | p | PEG n/total | MH n/total | p* | |

| n = 40 | n = 42 | |||||

| Anemia | 3 | 1 | 0.28 | 1/37 | 0/37 | 0.30 |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 0 | -- | 2/34 | 1/38 | 0.50 |

| Neutropenia | 4 | 2 | 0.36 | 3/33 | 1/37 | 0.27 |

| Lymphopenia | 1 | 0 | 0.30 | 0/36 | 0/39 | -- |

| Eosinophilia | 2 | 2 | 0.96 | 3/33 | 4/35 | 0.77 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/36 | 2/37 | 0.58 |

| Thrombocytosis | 1 | 3 | 0.32 | 1/36 | 0/39 | 0.30 |

| Elevated ureic nitrogen | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/37 | 0/38 | -- |

| Elevated creatinine | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/36 | 0/39 | -- |

| Elevation of AST | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/36 | 1/36 | 0.32 |

| Elevation of ALT | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/35 | 4/33 | 0.17 |

| Elevation of ALP | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/35 | 1/38 | 0.95 |

| Direct hyperbilirubinemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/37 | 0/37 | -- |

| Indirect hyperbilirubinemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/ 36 | 0/37 | 0.31 |

| Hypernatremia | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/36 | 1/37 | 0.98 |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/36 | 2/36 | 0.57 |

| Hyperchloremia | 0 | 0 | -- | 6/31 | 5/34 | 0.67 |

| Hypercalcemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/37 | 0/39 | -- |

| Hypocalcemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/36 | 0/39 | 0.30 |

| Hyperphosphatemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 1/35 | 3/36 | 0.34 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/36 | 0/39 | -- |

| Hypermagnesemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/37 | 0/39 | -- |

| Hypomagnesemia | 0 | 0 | -- | 0/37 | 0/39 | -- |

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; MH: magnesium hydroxide or milk of magnesia; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

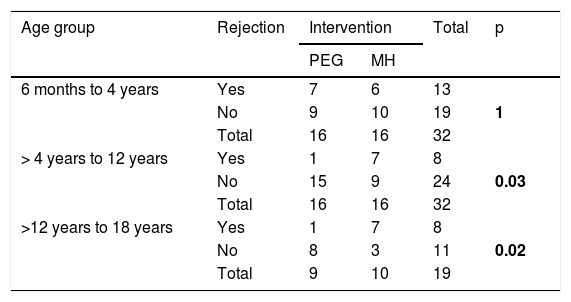

The overall analysis of the two intervention groups showed no significant differences between groups, regarding the number of laxative doses rejected or the number of patients that rejected the medication at 1, 3, 6, 9, or 12 months of treatment.

In the age subgroup analysis, a significantly higher number of patients rejected the MH in the subgroups > 4 years to 12 years and > 12 years to 18 years (p = 0.037 and p = 0.020, respectively) (Table 6).

Number of patients that rejected the medication, by intervention group and age subgroup.

| Age group | Rejection | Intervention | Total | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG | MH | ||||

| 6 months to 4 years | Yes | 7 | 6 | 13 | |

| No | 9 | 10 | 19 | 1 | |

| Total | 16 | 16 | 32 | ||

| > 4 years to 12 years | Yes | 1 | 7 | 8 | |

| No | 15 | 9 | 24 | 0.03 | |

| Total | 16 | 16 | 32 | ||

| >12 years to 18 years | Yes | 1 | 7 | 8 | |

| No | 8 | 3 | 11 | 0.02 | |

| Total | 9 | 10 | 19 | ||

MH: magnesium hydroxide or milk of magnesia; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

No differences were found in the weekly number of bowel movements or FI episodes by group at 1, 3, 6, 9, or 12 months of follow-up. Only one patient presented with fecal impaction after one week of treatment with PEG and was immediately removed from the study. No patients needed to take extra laxatives or have enemas. The required maintenance dose for achieving the treatment goal (1 to 3 bowel movements of soft consistency per week, and no abdominal pain or FI) was 0.91 ± 0.37 g/kg/day of PEG and 1.83 ± 0.39 ml/kg/day of MH.

DiscussionThe present study is the first to compare two osmotic laxatives that are widely used in the general pediatric population (PEG vs MH), for treating FC over a 12-month period, in children of different age groups, including infants from 6 months of age, that comparatively evaluates effectiveness, safety, and acceptability, to offer an alternative that is adequate for the age and clinical condition of the patient. Chronic FC is a very frequent condition in pediatrics. Its management requires interventions directed at improving diet, as well as bowel movement habits. Nevertheless, the importance of the prolonged use of laxatives is well-known, both for cleansing the colon and keeping it clean, not only improving patient quality of life, but also favoring the recovery of the colon and its motility. Even though there are numerous types of laxatives, the literature has demonstrated that osmotic laxatives are universally preferred for treating pediatric patients; in addition to being effective they are safer, but their long-term acceptability may not be good.5,6 PEG solution with electrolytes has been used for carrying out disimpaction in patients with chronic constipation,25–29 for cleansing the gastrointestinal tract prior to performing diagnostic and surgical procedures,30,31 and for treating chronic constipation in adults32,33 and children.34 Given the problems related to electrolyte absorption,9 PEG 3350 without electrolytes was approved in 1990 as a laxative for adults.35,36 Since then, several pediatric studies on PEG without electrolytes for the treatment of FC have been published. The majority have compared PEG with lactulose, showing that PEG without electrolytes is significantly more effective than lactulose.15–18 Given the poor quality of evidence of studies comparing PEG and MH, in the latest guidelines, experts from the NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN have recommended PEG (and lactulose as an alternative option) as first-line therapy for treating FC and MH and stimulating laxatives as second-line therapy, or as an added treatment.4

Milk of magnesia, the name commonly utilized to refer to MH, is an osmotic laxative that is widely available in Mexico and is much less expensive than PEG. One month of treatment with PEG 3350 (a 225 g bottle of Contumax powder) for a patient that weighs 20 kg costs $540.00 MXN vs $172 MXN for one month of treatment with MH (a 360 ml bottle of Milk of Magnesia Normex). The considerable difference in cost, the wide availability of MH, the low number of studies that compare PEG with MH, especially for a long period of time (12 months), and the fact that the one such study19 does not include infants as young as 6 months of age, all reflect the importance of carrying out a comparative study on PEG and MH. Consequently, we conducted our study on a pediatric population from 6 months to 18 years of age, dividing them into age subgroups, to evaluate the possible differences in efficacy, safety, and acceptance of the laxatives between subgroups.

Our study demonstrated that both laxatives were equally effective, in all age groups, similar to that reported by Loening-Baucke et al.19 in their randomized study, in which they compared PEG 3350 without electrolytes and MH for 12 months. Other authors have compared PEG with MH in patients from 12 months of age, but did not include younger infants, and maximum treatment duration was 6 months.20,21 Their results are conflicting, given that in the study by Ratanamongkola et al.,20 PEG was more effective than MH,21 and in the analysis by Gomes et al.,21 as in ours, PEG and MH were equally effective. Our evidence, added to that provided by other authors,20,22 lends strength to the concept that PEG and MH have the same efficacy. In our study, the use of PEG and MH was equally safe, both clinically and biochemically, over a 12-month period, in children as young as 6 months of age. The main adverse events detected were gases, cramps, FI, and diarrhea, all of which improved upon reducing the dose of the laxative, coinciding with data reported by other authors.11,19–21 However, it is important to consider that no infants below one year of age, receiving treatment for 12 months, were included in the previously published studies. As in the present study, the comparative studies on PEG and MH published at present, report that the two laxatives are safe, but only Loening-Baucke et al.19 evaluated their safety from both the clinical and the biochemical perspective. Ratanamongkola et al.20 only analyzed clinical adverse events and Gomes et al.21 did not evaluate safety. Our study contributes safety knowledge about PEG and MH for treating FC, even in younger infants, from 6 months of age, for a 12-month treatment period. Nevertheless, given the small number of infants of that age included in each treatment group, studies with a higher number of patients under one year of age are needed to strengthen that evidence. Five patients treated with MH reported having painful bowel movements, despite soft stool consistency. We do not know the reason for that symptom, which was considered mild and unrelated to having traumatic bowel movements. It was not a constant symptom and did not affect treatment continuity.

The overall acceptance of PEG and MH was similar, but upon performing the analyses by age subgroup, we found that a significantly higher number of patients rejected MH in the subgroups > 4–12 years of age and > 12–18 years of age (p = 0.037 and p = 0.020, respectively) (Table 6). Those findings coincide with the results of the Loening-Baucke et al. group,19 whose youngest patients were 4 years of age. Perhaps it has something to do with the poor palatability of MH and the higher quantity of laxative required for those groups of patients. We suggest taking that into account when choosing its treatment. Studies conducted on patients from 1 to 5 years of age for 6-month periods showed better acceptance of PEG, over MH. However, those authors did not specify how said acceptance was evaluated, nor did they show a comparative analysis.21,22

Study limitationsDue to the different forms of presentation and textures of PEG (powder) and milk of magnesia or MH (liquid), conducting a blinded study was not possible. Another limitation was that 9 patients from each group abandoned the study before its completion. But importantly, 8 of the 9 patients that abandoned the study before it ended met the success criteria at the time of abandonment, in each treatment group, and so cannot be considered treatment failures.

ConclusionBoth PEG and MH are equally effective in the management of FC in pediatric patients, as young as 6 months of age. PEG was better accepted than MH by patients above 4 years of age, and even better by patients above 12 years of age. Therefore, we suggest considering the age of the patient, together with treatment costs, before prescribing either of the two laxatives. Both are safe for treating infants under 12 months of age for a period of 12 months. Nevertheless, further comparative studies on that age group are needed to strengthen that concept. Based on our findings, MH can also be recommended as first-line treatment for FC in children under 4 years of age, and for cases in which PEG is not available or economically accessible.

Financial disclosureThis work received financial support from Federal Funds, as registered in the archives of the Local Research and Ethics Committee of the HIMFG (HIM/2007/032/SSA-759 and 1062).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Worona-Dibner L, Vázquez-Frias R, Valdez-Chávez L, Verdiguel-Oyola M. Ensayo clínico controlado sobre la eficacia, seguridad y aceptabilidad de polietilenglicol 3350 sin electrolitos vs hidróxido de magnesio en estreñimiento funcional en niños de 6 meses a 18 años. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2023;88:107–117.