Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is very prevalent in the general population, with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, requiring accurate diagnosis and treatment.

AimThe aim of this expert review is to establish good clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and personalized treatment of GERD.

MethodsThe good clinical practice recommendations were produced by a group of experts in GERD, members of the Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología (AMG), after carrying out an extensive review of the published literature and discussing each recommendation at a face-to-face meeting. This document does not aim to be a clinical practice guideline with the methodology such a document requires.

ResultsFifteen experts on GERD formulated 27 good clinical practice recommendations for recognizing the symptoms and complications of GERD, the rational use of diagnostic tests and medical treatment, the identification and management of refractory GERD, the overlap with functional disorders, endoscopic and surgical treatment, and GERD in the pregnant woman, older adult, and the obese patient.

ConclusionsAn accurate diagnosis of GERD is currently possible, enabling the prescription of a personalized treatment in patients with this condition. The goal of the good clinical practice recommendations by the group of experts from the AMG presented in this document is to aid both the general practitioner and specialist in the process of accurate diagnosis and treatment, in the patient with GERD.

La enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico (ERGE) es muy prevalente en población general, con un amplio espectro de manifestaciones clínicas que requiere de un diagnóstico y tratamiento de precisión.

ObjetivoEsta es una revisión de expertos que establece recomendaciones de buena práctica clínica para el diagnóstico y tratamiento personalizado de la ERGE.

MétodosLas recomendaciones de buena práctica clínica se generaron por un grupo de expertos en ERGE, miembros de la Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología (AMG), después de hacer una extensa revisión de la literatura publicada y la discusión de cada recomendación en una reunión presencial. Este documento no pretende ser una guía de práctica clínica con la metodología que este formato requiere.

ResultadosQuince expertos en ERGE elaboraron 27 recomendaciones de buena práctica clínica para el reconocimiento de síntomas y complicaciones de la ERGE, uso racional de pruebas diagnósticas y tratamiento médico de los diferentes fenotipos, identificación y manejo de la ERGE refractaria, de la sobreposición con trastornos funcionales, del tratamiento endoscópico y quirúrgico y sobre la ERGE en el embarazo, adulto mayor y en el paciente obeso.

ConclusionesActualmente es posible un diagnóstico de precisión en la ERGE que permite prescribir un tratamiento personalizado en los pacientes con esta condición. Las recomendaciones de buena práctica clínica del grupo de expertos de la AMG presentadas en este documento pretender ayudar al médico general y al especialista en el proceso del diagnóstico y tratamiento de precisión del paciente con ERGE.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition that affects approximately one in every five adults in the general population. It encompasses a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations and significantly affects patient quality of life. There are different diagnostic tests and diverse therapeutic modalities for the condition. It is currently possible to make an appropriate diagnostic evaluation that enables the identification of the GERD phenotype and indication of accurate treatment for the patient. The aim of the present review is to make good clinical practice recommendations for the gastroenterologist and general practitioner, based on recent scientific evidence discussed by a group of experts on GERD.1–5

MethodsThe present expert review was commissioned by the Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología (AMG). The specialists were selected, based on their renowned career in academic teaching, research, and healthcare, with a special interest in GERD. An extensive review of the literature, spanning the past 20 years, was carried out on GERD and its diagnostic tests and treatment. The experts were divided into five working groups, to review the literature and formulate recommendations on: 1) recognition of typical symptoms, extraesophageal symptoms, and complications of GERD; 2) the rational use of diagnostic tests; 3) accurate treatment based on endoscopic phenotypes and measurements of gastroesophageal reflux; 4) endoscopic and surgical treatment of GERD; and 5) GERD in special populations. Version 1.0 of the recommendations for each of the groups was discussed and voted on by all the experts at a face-to-face meeting. Version 2.0 of the statements, created at the face-to-face meeting, were reviewed again, and corrected by each of the groups, resulting in version 3.0 of the statements. Said version underwent a final review by all the participants, for their final approval, culminating in the document presented herein.

Recognition of typical symptoms, extraesophageal symptoms, and complications of gastroesophageal reflux diseaseDefinitionGastroesophageal reflux disease is defined as a condition that develops when the ascent of gastric content causes symptoms and/or complications that affect the quality of life of the person experiencing them.

Patients can be diagnosed with GERD, based on clinical manifestations and objective tests that show gastroesophageal reflux, such as esophageal pH monitoring or the endoscopic demonstration of esophageal lesions or esophagitis.

The clinical manifestations of GERD are classified into esophageal syndromes and extraesophageal syndromes. The former are subdivided into symptomatic syndromes and syndromes with mucosal lesions. Symptomatic syndromes are chest pain due to reflux and nonerosive GERD (NERD). Syndromes with mucosal lesions are erosive esophagitis (EE), stricture, Barrett’s esophagus (BE), and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus (ACE).1

There are three phenotypical presentations of GERD. The most frequent is NERD, which is found in 60-70% of patients, followed by EE in 30% and BE in 6-8%.2

Fifty percent of all patients with heartburn and normal endoscopy have an abnormal acid exposure time (AET) and belong to the group of patients with NERD. The remaining 50% have a normal AET, with the so-called esophageal functional disorders, which are divided into functional heartburn (60%) and reflux hypersensitivity (40%).3

Extraesophageal syndromes are classified into those with an established association (cough, laryngitis, asthma, and dental erosions) and those with a possible association (pulmonary fibrosis, otitis media, sinusitis, and laryngitis).1

EpidemiologyGERD is a frequent disease, with a varying prevalence worldwide, estimated at 20% in the general population.

In a systematic review of the epidemiology of GERD, defined as heartburn and/or regurgitation once a week, prevalence was reported at 10-20% in the Western world and below 5% in Asia.4 In a more recent study, the estimated range of prevalence was 18.1-27.8% in North America, 8.8-25.9% in Europe, 2.5-7.8% in Asia, 8.7-33.1% in the Middle East, 11.6% in Australia, and 23.0% in South America. Evidence suggests an increase in prevalence since 1995, particularly in North America and Asia.5 The prevalence of symptoms in North America, Europe, and Southeast Asia has increased by 50%, in relation to the prevalence reported in the mid 1990s, but it appears to have since leveled off.5

Obesity and smoking are risk factors. Obesity has an odds ratio (OR) of 1.73 and is associated with EE (OR 1.59), BE (OR 1.24), and ACE.6

The decrease in the prevalence of gastritis due to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has been mentioned as a possible explanation for the increase in GERD, but no consistent association has been found between GERD symptoms and the presence of H. pylori or the response to eradication treatment. A meta-analysis showed no increased risk for developing symptoms of GERD after eradication treatment. In clinical trials, eradication was not consistently associated with the de novo development of GERD.2 Eradication does not appear to affect cure or recurrence in pre-existing GERD. Accumulated data suggest that H. pylori is a possible preventive factor against EE, BE, and ACE. This effect is attributed to the decrease in the production of acid from gastric body gastritis and gastric atrophy, leading to a decrease in esophageal exposure to acid.2

Tobacco use is weakly associated with symptoms of GERD (OR 1.26). The relation is supported by a longitudinal study, in which the individuals that decreased their smoking had a three-times higher decrease in symptoms of regurgitation and heartburn, than those that continued to smoke.7 Smoking is an important factor for the development of EE and ACE.6

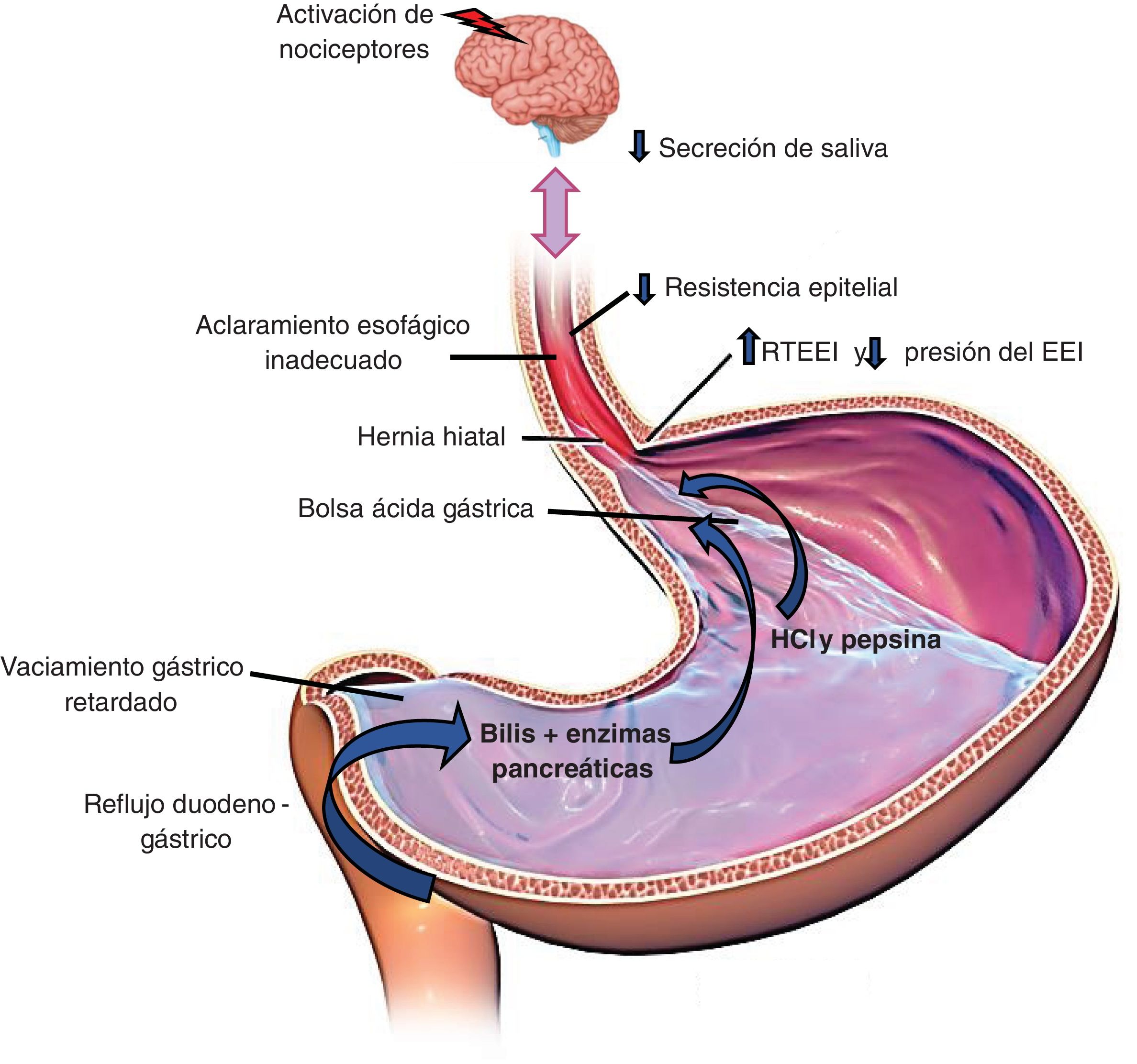

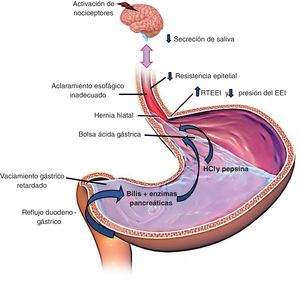

The pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux diseaseThe pathophysiology of GERD is multifactorial.

GERD is caused by the return of acid through an incompetent lower gastroesophageal sphincter, with or without the presence of hiatal hernia (HH).

The main mechanisms for preventing reflux are the esophagogastric junction (EGJ), composed of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and the crural diaphragm (CD); the esophageal clearance of the refluxed material through primary and secondary peristalsis; and the chemical clearance through the neutralization of acid by salivary bicarbonate.8Fig. 1 illustrates these pathophysiologic mechanisms.

The factors that favor gastric content reflux into the esophagus follow below.

Alteration of the antireflux barrier:

- -

Transient LES relaxation (TLESR). This phenomenon is mediated by the vagus nerve and characterized by relaxations not preceded by swallowing. They frequently occur in the postprandial period and are induced by gastric distension. TLESR is the most common mechanism associated with episodes of reflux.9

- -

HH. The presence of HH causes loss of the antireflux barrier formed by the EGJ. Esophageal acid exposure has been shown to be greater in patients with HH. In addition, refluxed material can accumulate in the hernia sac, causing new reflux episodes. Patients with large HHs have severe reflux disease and many patients with milder disease have evidence of smaller HHs.10,11

- -

Reduced LES pressure. An incompetent LES is more common in EE, BE, and HH.

Gastric factors:

- -

Acid pocket. Gastric acid not neutralized by food is accumulated in the acid pocket after a meal. It tends to be located under the EGJ in a normal subject. In patients with GERD, the acid pocket extends to the distal esophagus, especially in the presence of large HHs, and is responsible for the episodes of postprandial reflux.2

- -

Delayed gastric emptying. Approximately 30% of patients with GERD have delayed gastric emptying; this mechanism favors TLESRs and the possibility of having reflex episodes.

Esophageal sensitivity: esophageal sensitivity plays a role in GERD. Symptoms can correlate with the components of the refluxed material. Acid, the proximal extension of the reflux, and gas favor symptom perception.12

Some patients with reflux are more sensitive to acid and said sensitivity can be associated with altered mucosal integrity. Reflux episodes that reach the proximal esophagus have a greater symptomatic association and can be related to the superficial location of the afferent nerves of the mucosa in the upper third of the esophagus.13

Typical symptoms and extraesophageal manifestationsRecommendation 1. The presence of typical symptoms, such as heartburn and regurgitation, or extraesophageal manifestations, such as cough, laryngitis, bronchial asthma, or dental erosions, suggest the possibility of GERD and require an appropriate diagnostic evaluation.

The typical symptoms of GERD are heartburn and regurgitation.14 Heartburn is defined as a retrosternal burning sensation that ascends from the stomach to the mouth. It occurs especially after abundant fatty meals or the ingestion of spicy foods, citrus products, chocolate, or alcohol. Supine or forward-leaning positions favor regurgitation. Nocturnal heartburn can cause sleep disturbances and affect daily activities. Sleep deprivation, as well as psychologic factors, have been reported to increase the perception of heartburn.15 The frequency and intensity of heartburn is not associated with the grade of damage to the esophageal mucosa. Regurgitation is defined as the effortless return of the gastric content into the esophagus and can reach the mouth.6 These symptoms have little sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing GERD. The diagnosis of GERD based on symptoms has 67% sensitivity and 70% specificity.16

Chest pain is another symptom associated with GERD. It can be indistinguishable from pain due to ischemic heart failure. GERD is the most frequent cause of noncardiac chest pain.6

For a patient to be considered to have GERD, and not just gastroesophageal reflux, he/she must present with mild symptoms two or more days per week or moderate or severe symptoms at least one day a week. These symptoms affect the quality of life of the patient.1

Dysphagia, hiccups, and burping are other symptoms associated with GERD. Dysphagia is considered an alarm symptom and always requires an endoscopic diagnostic evaluation.

The extraesophageal manifestations that have an established association with GERD are cough, laryngitis, asthma, and dental erosions. An attempt has been made to associate numerous symptoms with GERD, but the evidence on causality is still a subject of debate. Pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis, pulmonary fibrosis, and globus are among said possible symptoms.6 The pathophysiologic mechanisms of those manifestations are the direct damage by the acid (microaspiration) or the indirect damage (the presence of acid in the esophagus induces a vagal reflex).7 Extraesophageal syndromes are thought to usually have a multifactorial cause and GERD is considered one of several potential aggravating factors. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate and carry out objective tests to demonstrate that GERD is the cause of those manifestations.17

Complications of gastroesophageal reflux diseaseRecommendation 2. Peptic stricture, gastrointestinal bleeding, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma are complications of GERD and should be suspected in populations with risk factors, such as symptoms of more than five-year progression, obesity, male sex, age above 50 years, and smoking.

Men are at greater risk for presenting with EE, BE, and ACE.6 Advanced age is inconsistent with an increased risk for GERD symptoms but is related to the development of complications and hospitalization due to esophageal stricture.18

In the United States, prevalence of GERD symptoms appears to be similar between the different races, but Whites are at higher risk for EE, stricture, BE, and ACE.18

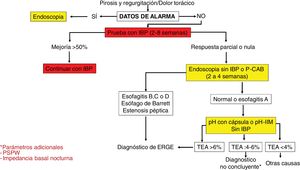

The rational use of diagnostic testsProton pump inhibitor testRecommendation 3. In patients with heartburn and regurgitation, with no alarm symptoms, we recommend a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) test, at the standard dose, for two to four weeks, and in cases of noncardiac chest pain, for four to eight weeks.

The PPI test is habitually employed in clinical practice and is recommended by the international guidelines. The PPI should be taken 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast for two to four weeks for typical GERD symptoms, with no alarm symptoms, and for four to eight weeks for noncardiac chest pain. If patients show a 50% improvement in symptoms, they should be treated as a patient with GERD. After four to eight weeks of continuous treatment, either an on-demand regimen is indicated, or the PPI is suspended. In cases of symptom relapse or inadequate response, endoscopy should be performed, after having suspended the PPI for a period of two to four weeks.19,20 This test has limitations, such as the lack of dose standardization, type of PPI, and treatment duration. A placebo effect has also been seen in 20% of patients.8,21,22 The diagnostic yield of the PPI test in patients with typical symptoms has 79% sensitivity (95% confidence interval [CI], 72-84%) and 45% specificity (95% CI, 4-49%), utilizing endoscopy and 24-h esophageal pH monitoring as the reference standard. In patients with noncardiac chest pain, sensitivity and specificity of the PPI test is 79% (95% CI, 69-86%).23

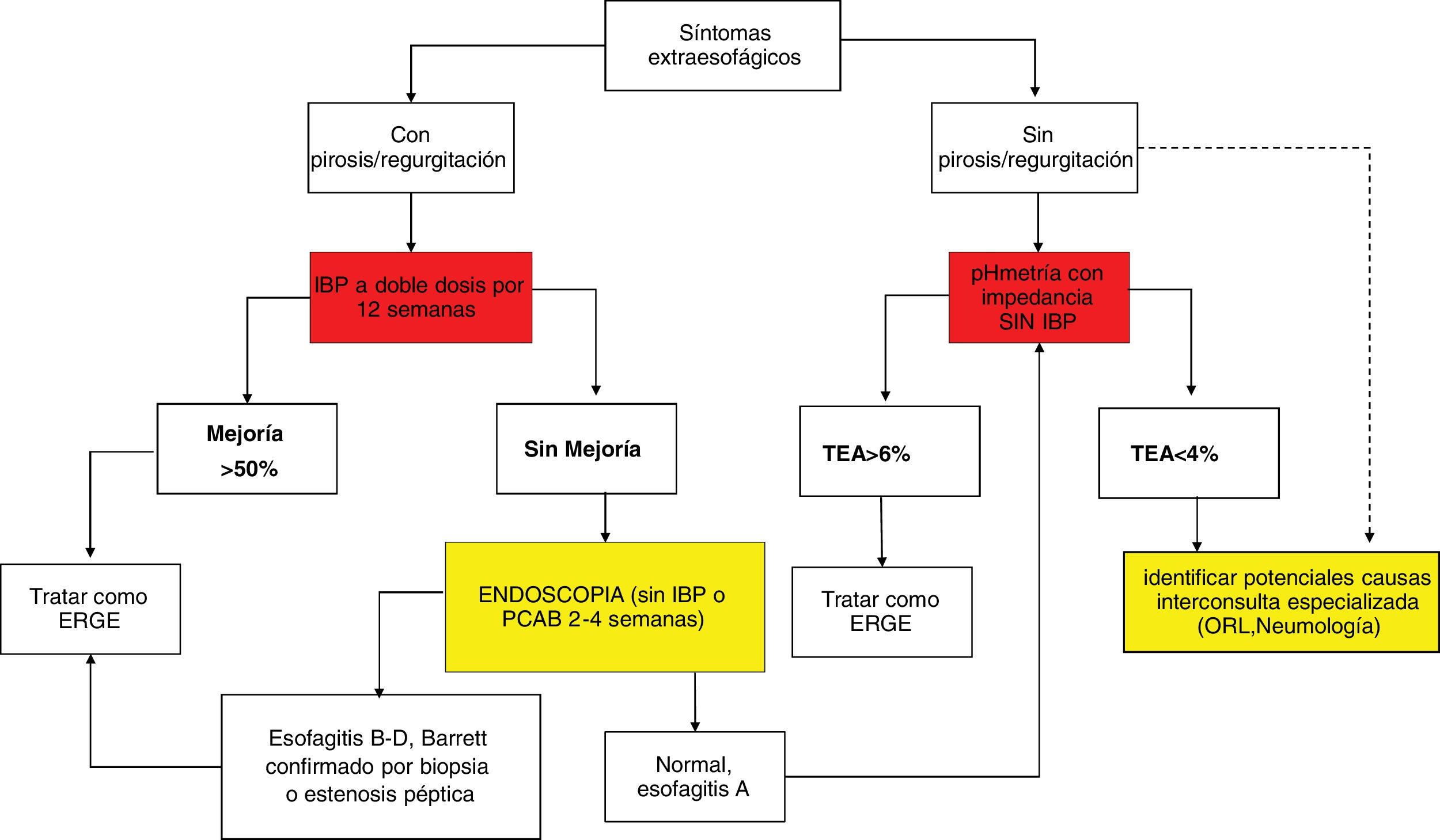

Recommendation 4. In patients with extraesophageal manifestations and typical symptoms of GERD, we recommend a double-dose PPI test for 12 weeks. In patients with extraesophageal symptoms with no typical symptoms of GERD, we recommend performing objective diagnostic tests.

PPI test use has been extrapolated to patients with extraesophageal symptoms (dysphonia, cough, asthma) and proposed as a diagnostic and therapeutic method. However, results of its efficacy are inconsistent. A first meta-analysis found that the PPI test did not improve said symptoms, compared with placebo (relative risk [RR] 1.28, 95% CI 0.94-1.74).24 In contrast, in two recent meta-analyses, the patients had a significantly higher response rate, compared with placebo (risk difference = 0.15; 95% CI 0.01-0.30) and a moderate superiority of PPI over placebo in laryngopharyngeal reflux (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.03-1.67).25,26

Extraesophageal symptom improvement should not be taken as confirmatory proof of GERD due to the placebo effect, multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms, and different extraesophageal manifestations.24 Nevertheless, the PPI test twice a day for 12 weeks is recommended in patients with extraesophageal symptoms, who have typical reflux symptoms. Patients with extraesophageal manifestations, but in whom heartburn and regurgitation are absent, should be studied through objective diagnostic tests for GERD.17,20

EndoscopyRecommendation 5. We recommend diagnostic endoscopy in patients with alarm symptoms or at risk for BE, patients that do not respond to a PPI test, and patients that present with symptom recurrence upon suspending the PPI or potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs).

Endoscopy is the most useful test for evaluating the esophageal mucosa. The presence of EE, BE, and esophageal stricture are diagnostic findings of GERD. The Los Angeles (LA) classification of EE continues to be the most useful validated scale.27 Due to interobserver variability, different expert consensuses establish that LA classification A of EE is not definitive evidence of GERD.14,28 EE grades B, C, and D are considered diagnostic of GERD. The finding of a BE segment > 3 cm on biopsy is definitively diagnostic of GERD, with no need to measure reflux. In cases of severe EE (LA classification C/D), the recommendation is to repeat endoscopy after double-dose PPI treatment for eight weeks, to evaluate the healing of the mucosa and rule out BE, which can be difficult to detect when there is severe inflammation.19,20

To increase diagnostic yield in GERD, endoscopy should be performed two weeks, and ideally even four weeks, after PPI suspension. In a study that compared clinical and endoscopic characteristics of patients with GERD, utilizing logistic regression, the patients taking PPIs were more frequently classified as having NERD (OR: 3.2; p < 0.001).29 In a small prospective study on 12 patients with EE and mucosal healing, endoscopic and histologic changes were evaluated two weeks after suspending PPIs. At two weeks, the patients had endoscopic signs of EE and biopsies showed intercellular space dilation, an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes, and papillary hyperplasia.30

In the context of patients with GERD symptoms that do not respond to PPIs, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) must be ruled out. Therefore, the recommendation is to suspend PPIs two to four weeks before performing diagnostic endoscopy because there is evidence that PPIs can mask endoscopic and histologic findings of EoE.31 During the two to four weeks without PPIs, the use of antiacids for reflux symptom relief can be recommended.20

A complete endoscopic evaluation should be carried out, which includes assessing the presence of EE, the diaphragmatic hiatus, the axial length of the HH, and BE inspection. As stated above, examining whether there is EE and reporting it according to the LA classification should be done during the endoscopic evaluation. The Hill classification should be used to describe the diaphragmatic hiatus over the gastroesophageal valve in retrovision and with gastric insufflation (grades I and II are normal); grades III and IV have been independently associated with poor therapeutic response to PPIs and with the presence of EE.32,33 BE should be evaluated according to the Prague classification; when biopsies are taken, the Seattle protocol should be used.34

Gastroesophageal reflux measurement: pH-impedance, wireless capsule, mucosal impedanceRecommendation 6. In patients with no previous signs of GERD at endoscopy and with refractory symptoms to antisecretory therapy, we recommend carrying out wireless capsule pH monitoring or pH-impedance testing without treatment. In patients with previous signs of GERD at endoscopy and refractory symptoms, we recommend evaluation through pH-impedance testing with treatment.

Ambulatory reflux measurement has two configurations: with a catheter or with a wireless capsule. The Bravo® wireless capsule (Medtronic™, Minneapolis, MN, USA) is placed during endoscopy in the distal esophagus (6 cm proximal to the squamocolumnar junction), utilizing a suction and clipping mechanism.35 Exposure to acid can be measured with this technique for up to 96 hours and the relation between the symptoms reported by the patient and reflux episodes can be evaluated. It is better tolerated but more costly.19,36 In catheter-based pH monitoring, a pH probe is introduced transnasally and placed 5 cm above the upper edge of the LES, identified through manometry. This technique measures AET in the distal esophagus for 24 hours and establishes the association between symptoms and reflux episodes. The pH catheters can also be combined with multichannel intraluminal impedance (MII-pH), utilizing impedance rings, to evaluate the movement of air and fluids through the esophagus (anterograde-retrograde), regardless of the pH, and classify them into acid, weakly acid, weakly alkaline, gas, liquid, or mixed.8

AET is the most reproducible metric and the best predictor of response to drug or surgical treatment. According to the Lyon 2.0 consensus, normal or physiologic AET should be < 4%. AET > 6% is definitely pathologic. A value between 4-6% is considered an inconclusive gray zone, requiring additional parameters, such as the number of reflux episodes determined through impedance, mean nocturnal baseline impedance (MNBI), and symptomatic association. The number of reflux episodes < 40 in 24 hours is considered normal, > 80 is abnormal, and between 40 and 80 is inconclusive. An MNBI < 1,500 Ohms supports the diagnosis of GERD, whereas an MNBI > 2,500 Ohms rules it out. The post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index (PSPWI) can support the diagnosis of GERD when it is below 60%.37 In a double-blind clinical trial on patients with heartburn, regurgitation and/or chest pain, and partial response to PPIs, they underwent wireless capsule reflux measuring without PPIs (after seven-day PPI suspension), followed by PPI suspension for another two weeks, to complete the three-week PPI suspension study intervention. AET was < 4% during the four days of monitoring, with an OR of 10.0 (95% CI) for predicting successful PPI suspension.37 Thus, wireless capsule pH monitoring (up to 96 hours) is the method of choice for objectively evaluating the esophageal symptoms of GERD. In patients with typical symptoms associated with excessive burping, suspected rumination, or extraesophageal symptoms, 24-h MII-pH is recommended, given that impedance enables burping episodes or rumination and their association with reflux episodes to be detected.14,20

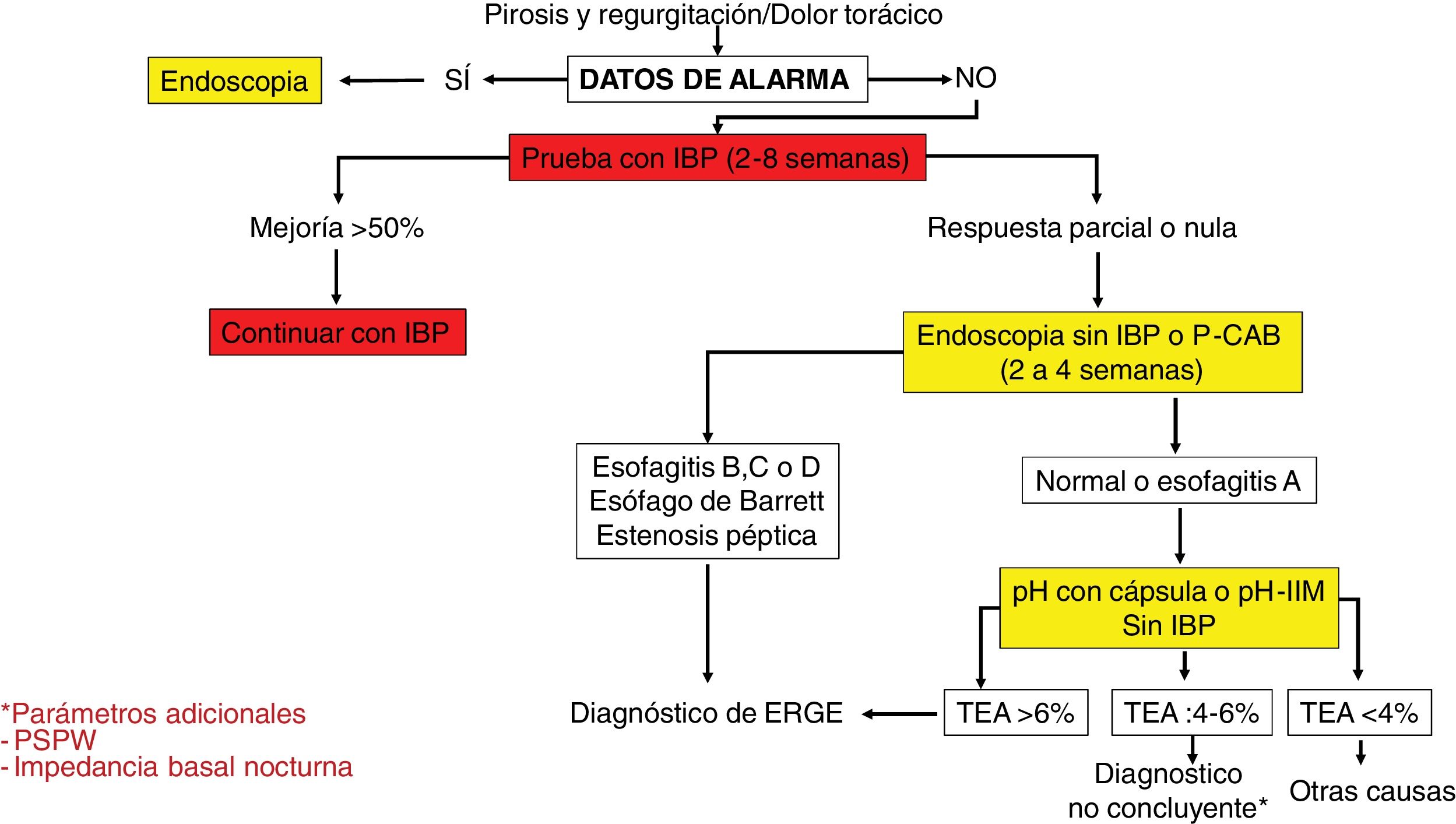

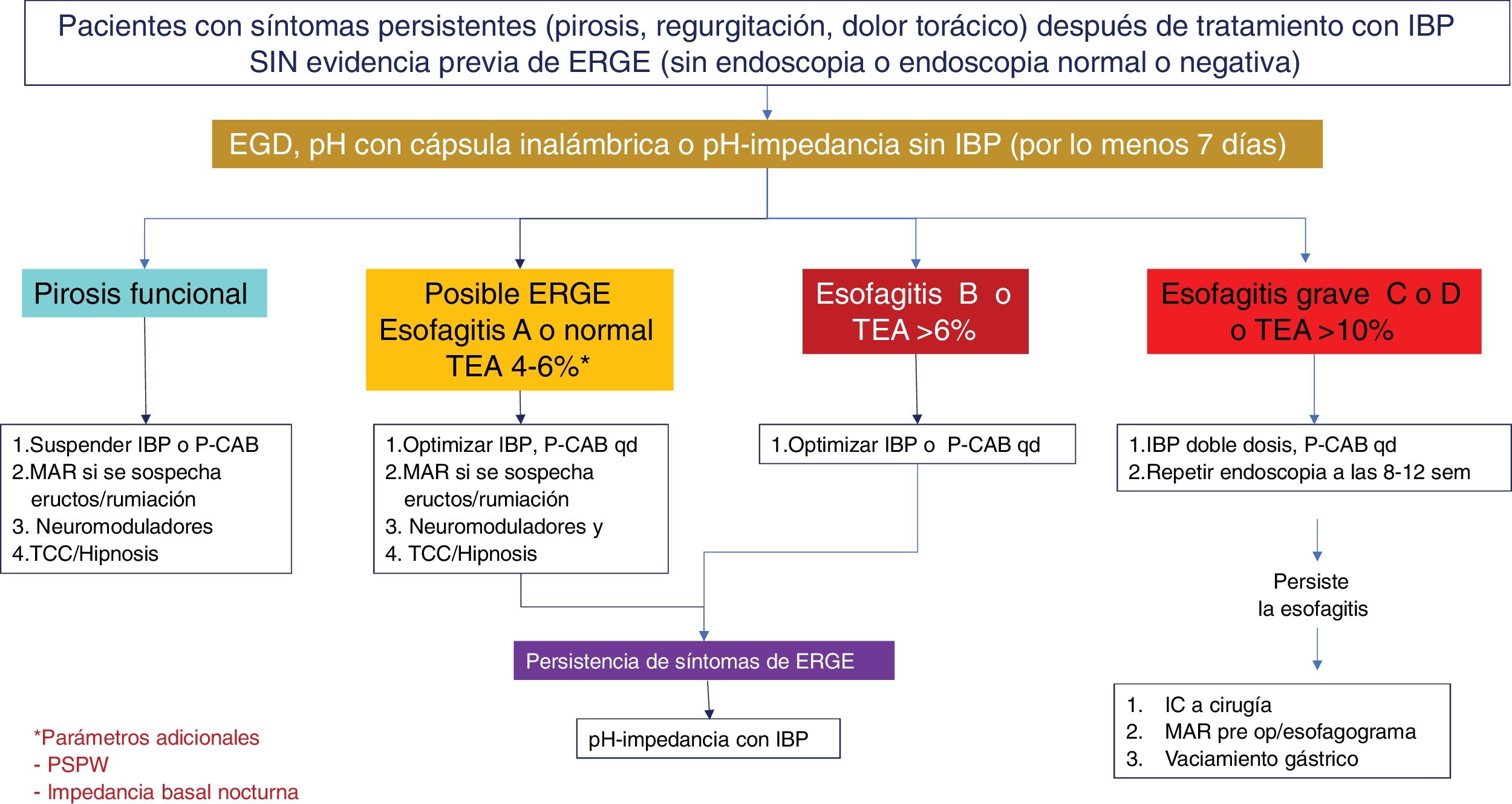

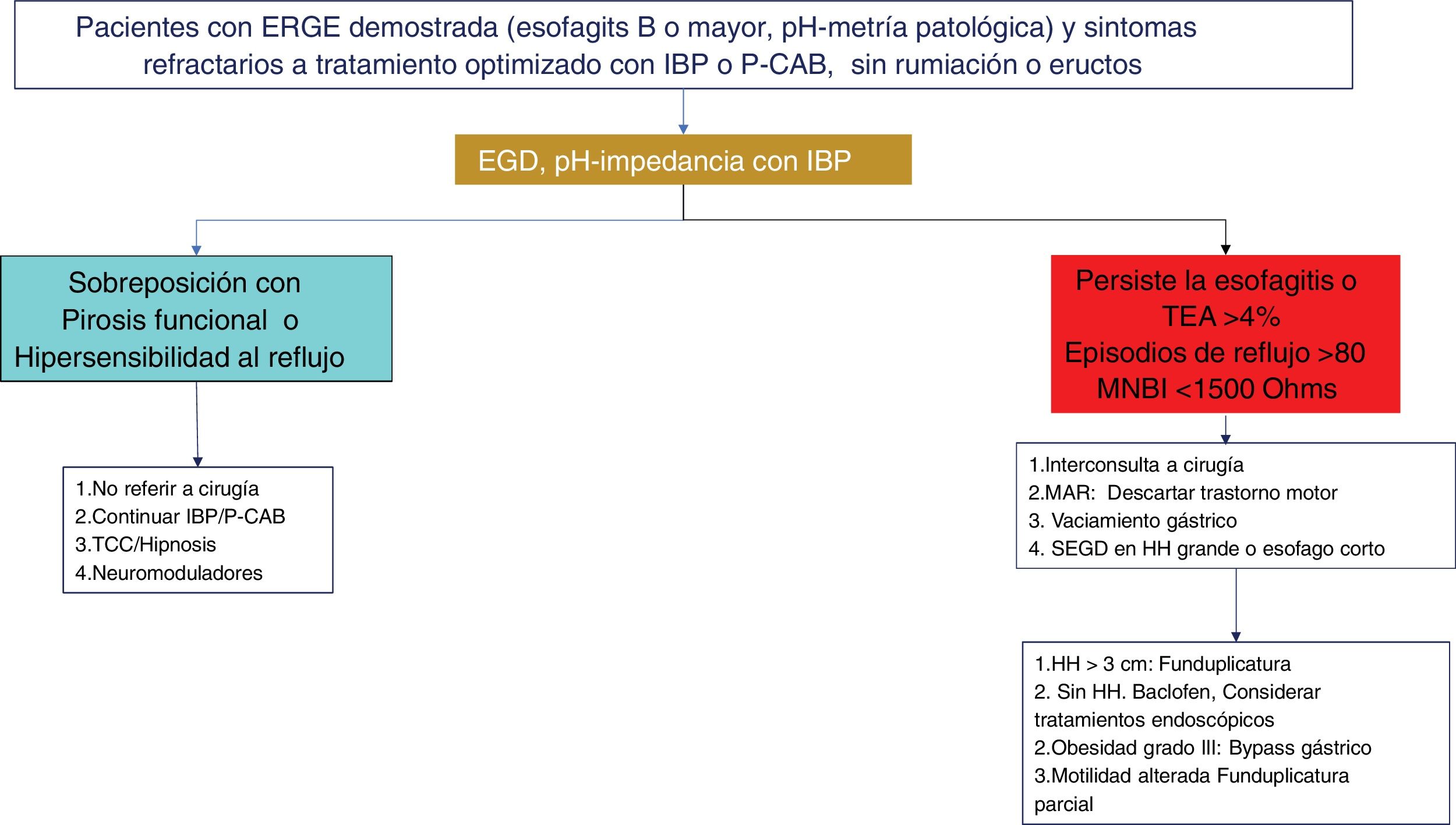

Twenty-four-hour MII-pH with double-dose PPI is the method of choice for the ambulatory monitoring of reflux in patients with prior signs of GERD and persistent symptoms, despite optimum treatment. With respect to AET values and the number of reflux episodes in a MII-pH conducted with PPIs, a retrospective study that included healthy volunteers and patients with proven GERD, established that an AET > 0.5% and/or number of reflux episodes > 40 has 86% sensitivity and 36% specificity for symptom persistence, and an overall improvement of 79% after surgical management.38 The combination of an AET > 4% and > 80 reflux episodes/day, with optimum antisecretory treatment, is evidence of refractory GERD.14 MII-pH with PPIs in this group of patients aids in determining which patient has refractory GERD and would benefit from treatment scaling, as well as identifying whether there is overlapping with an esophageal functional disorder39 (Figs. 2–4).

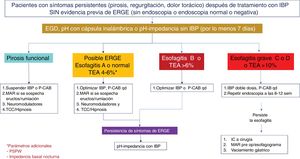

Diagnostic algorithm in patients with typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease or noncardiac chest pain.

AET: acid exposure time; MII-pH: multichannel intraluminal impedance; P-CABs: potassium-competitive acid blockers; PPIs: proton pump inhibitors; PSPW: post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave.

Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that are refractory to treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), with no previous objective evidence of GERD. This group of patients should undergo a new endoscopy after having suspended PPIs for two to four weeks. Patients with normal endoscopy or esophagitis A should undergo reflux measurement with a wireless capsule or pH impedance testing without a PPI. Patients showing Los Angeles classification esophagitis B, C, or D, or acid exposure time (AET) > 6% require optimization of treatment with a PPI or the switch to a potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB). Endoscopy should be repeated in patients with severe esophagitis after eight weeks of treatment. The diagnosis of refractory GERD is made when there is persistent esophagitis, and those patients are candidates for antireflux surgery evaluation. Patients with normal endoscopy or esophagitis A and an AET of 4-6% require additional tests, such as post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave (PSPW) or nocturnal baseline impedance and high-resolution manometry (HRM) with impedance when burping or rumination is suspected. The patients with a functional disorder, such as reflux hypersensitivity or functional heartburn require treatment with neuromodulators or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Patients with esophagitis B or an AET > 6 or between 4 and 6% that persist with symptoms after treatment with a PPI or P-CAB should be studied through pH-impedance testing with antisecretory treatment.

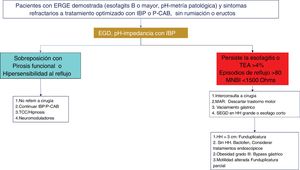

Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm in refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Patients with esophagitis B or higher or a pathologic acid exposure time (AET) and persistent symptoms after an optimized treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB) for eight weeks, should be studied through a new endoscopy (EGD) and/or pH impedance testing with treatment with a PPI. Patients with esophageal cicatrization failure, an AET > 4%, a number of reflux episodes > 80, or a mean nocturnal baseline impedance (MNBI) < 1,500 Ohms should be evaluated for antireflux treatment. Patients with GERD and functional disorder (functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity) overlapping should be treated with neuromodulators or psychologic therapies, in addition to continuing antisecretory treatment.

Recommendation 7. We do not recommend esophagogram for diagnosing GERD.

In the era of endoscopy, pH-monitoring, and high-resolution manometry (HRM), the esophagogram has been displaced regarding the diagnosis and management of GERD.40

In a study by Saleh et al., 20 patients were evaluated through esophagogram and compared with patients that underwent MII-pH, for the diagnosis of GERD. They reported 46% sensitivity, 44% specificity, a 50% positive predictive value (PPV), and a 40% negative predictive value (NPV), which is why esophagogram currently plays no role in the diagnosis of GERD.41 This test can be useful in the complementary evaluation of esophageal strictures and is mandatory in cases of suspected short esophagus.

Esophageal manometryRecommendation 8. High-resolution esophageal manometry is not recommended for diagnosing GERD. It is indispensable for the preoperative evaluation of the candidate for antireflux surgery.

In patients with GERD that do not respond to lifestyle changes or PPI therapy and have no relevant endoscopic findings, HRM is recommended to make the differential diagnosis, as well as to evaluate other factors that could be conditioning GERD.

Achalasia is an esophageal motility disorder, characterized by aperistalsis and a lack of relaxation of the EGJ. Patients clinically present with progressive dysphagia, heartburn from the acidification of retained food, regurgitation, and occasional chest pain, with or without weight loss, and so can clinically be confused with GERD, and in the majority of cases, the diagnosis is delayed.41 In patients with achalasia, HRM has 93-98% sensitivity and 96-98% specificity.42

Rumination syndrome and supragastric burping can be present in patients with typical reflux symptoms and poor response to PPI therapy. HRM with impedance is diagnostic in both disorders.43 Rumination is characterized by an increase in intra-abdominal pressure > 30 mmHg, a reflux event extending to the proximal esophagus, and upper esophageal sphincter relaxation. Excessive burps can be gastric or supragastric. Supragastric burping is characterized by the suction of pharyngeal air into the esophagus, followed by a muscle contraction, resulting in the abrupt expulsion of air, before reaching the stomach.44 In HRM with impedance, a contraction of the EGJ, negative intrathoracic pressures, and upper esophageal sphincter relaxation are seen, with aboral air flow illustrated by increases in impedance, followed by the expulsion of air. Three types of EGJ are identified through HRM: type 1: the LES and CD are superimposed; type 2: LES and CD are separated by < 3 cm; type 3: the LES and CD are separated by > 3 cm.45 Type 3 identifies HH.13 Esophageal manometry is a mandatory study in the evaluation of patients that are surgical candidates, to rule out the presence of major motility disorders, such as achalasia. The usefulness of manometry is controversial as a predictor of postoperative dysphagia. In general, the presence of aperistalsis contraindicates Nissen fundoplication and abnormal peristaltic reserve can suggest the performance of a loose Nissen or partial fundoplication. Manometry should be carried out to identify the upper edge of the LES and appropriate pH probe placement for catheter-based gastroesophageal reflux monitoring.

Diagnostic tests in extraesophageal manifestationsRecommendation 9. In patients with extraesophageal manifestations with no typical symptoms, we recommend the study of GERD through pH-impedance testing without a PPI or P-CAB. We do not recommend endoscopy or laryngoscopy for diagnosing GERD in patients with extraesophageal manifestations.

Otorhinolaryngologic manifestations unaccompanied by typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation have a low probability of association with GERD and vary, depending on the predominant manifestations: overall < 9% (range 10-59%), dysphonia (14.8%), chronic cough (7-13%), laryngitis (10.4%), asthma (4.8-9.3%), and globus (7%).46–48 Laryngoscopy has 86% sensitivity, 9% specificity, and 44% diagnostic accuracy, compared with MII-pH. The laryngoscopic findings of erythema, edema, lymphoid hyperplasia of the posterior larynx, ulcerations, subglottic stenosis, and nonspecific vocal cord polyps of GERD are not correlated with AET and do not predict response to PPI or fundoplication. They can also be seen in allergic disorders, infectious diseases, or in the healthy population.49–51 Therefore, laryngoscopy is not a useful diagnostic test for GERD. Endoscopy has 20-35% sensitivity in the presence of extraesophageal manifestations of GERD in this setting.48,52 AET measured through MII-pH has a varying sensitivity and specificity of 50-92% and 50-63%, respectively, with a PPV of 94% and a NPV of 58%, in the sole presence of extraesophageal manifestations. Pathologic AET (> 6%) without antisecretory treatment appears to predict response to PPIs, even though the pre-test probability is low, if the only symptom is cough, with no heartburn.14,48,52,53 Cost-effectiveness studies have reported that studying GERD through MII-pH as the strategy costs less than the PPI test for 12 weeks ($1,897 USD vs $3,033 USD). Thus, in addition to preventing overdiagnosis, it also prevents unjustified prolonged use of antisecretory agents.54–57 Upon comparing the diagnostic yield of catheter-based pH-monitoring, MII-pH, and wireless capsule-based pH-monitoring, the advantages of MII-pH are that it detects acid reflux, weakly acidic reflux, and non-acid reflux, as well as the total number of reflux episodes. It also enables nocturnal baseline impedance to be measured and identifies the overlap with functional disorders.56–58 The wireless capsule can be useful when transnasal catheters are not tolerated or when a negative result is highly suspected, but it is not superior to MMI-pH in evaluating otorhinolaryngologic symptoms. One of the problems that has been reported by researchers is the difficulty the patient has in registering episodes of cough, given that a difference has been shown between the time of onset of the cough and its registering in the portable pH system, increasing the false negatives of this test.59–61 The use of other techniques, such as oropharyngeal pH-monitoring, or Restech® (Respiratory Technology Corporation, Houston, TX, USA), or the measuring of pepsin in saliva, are not recommended because they have a low sensitivity of < 40%, and are poorly correlated with symptoms and MII-pH findings.62 Response to a PPI test varies between 14-28% in subjects with chronic cough with no typical symptoms, increases to 43% when the patient has an abnormal AET, and reaches 78% when cough is associated with heartburn, albeit specificity is generally low (14%).63 Due to the low probability of response to antisecretory treatment, several international guidelines currently recommend studying the presence of reflux to justify antisecretory therapy20,64 (Fig. 5).

Medical treatmentLifestyle modificationsRecommendation 10. Lifestyle modifications should be recommended in all patients with GERD, and they include weight loss in patients with overweight or obesity, eating an early dinner, bed head elevation, sleeping on the left side, and quitting smoking.

Different foods and drinks are associated with the appearance of reflux symptoms, and they include acidic foods, citrus fruits, spicy foods, high-fat foods, coffee, carbonated drinks, and alcoholic beverages, among others.65 Some dietary habits and patterns can also be related to the appearance of reflux symptoms (especially nocturnal events), such as eating large quantities of food before going to bed.66 Overweight and obesity, alcohol use, smoking, and the lack of consistent physical activity are the outstanding lifestyle factors related to GERD.67

The evidence supporting the role dietary and lifestyle factors play in GERD has some limitations. Despite the high prevalence of the disease, a relatively low number of studies have been conducted and the existing analyses have been carried out on small groups of patients, lack controls, report conflicting results, and have great variability and individual differences.68–70

More recent and better designed studies have determined that there is insufficient evidence for making a generalized recommendation to eliminate specific foods in GERD. At present, the most reasonable recommendation indicates that the elimination of reflux-triggering foods should be decided on individually, guided by the patient’s own experience.68

There is evidence that sleeping on the left side and bed head elevation reduce the development of reflux symptoms, mainly at night. Similarly, not eating at least two to three hours before going to bed and avoiding cigarette smoking can have beneficial effects on GERD.71

Obesity increases the risk of GERD, possibly due to the composition of diet and the increase of intra-abdominal fat that induce the physiologic changes that favor reflux. Better quality evidence refers to the positive effect of weight loss, controlled through diet and physical activity, on GERD.72,73

As the evidence supporting lifestyle changes becomes stronger, these are reasonable recommendations for patients with GERD as general health measures; in addition to helping control the disease, they contribute to better quality of life.

Proton pump inhibitorsRecommendation 11. PPIs are drugs of choice in the treatment of GERD. The standard dose is used for four weeks in NERD and for eight weeks in EE. In severe esophagitis (Los Angeles classification C or D), double-dose PPI for eight weeks is recommended.

PPIs are the most widely used drugs for treating GERD. They have been shown to be more effective than H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) for alleviating symptoms and healing lesions, and so are considered first-line drugs.74 They have 70 to 80% efficacy in EE and 50 to 60% efficacy in nonerosive disease.20 Delayed-release PPIs (omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, ilaprazole), dual delayed-release PPIs (dexlansoprazole), and immediate-release PPIs (omeprazole-sodium bicarbonate) are recommended at the standard dose for four weeks in NERD and eight weeks in erosive disease.19,20,75 In cases of severe esophagitis (LA classification C and D), a double-dose delayed-release PPI should be used for eight weeks.19,20,75 The symptom relief and esophageal cicatrization rate is similar among the seven PPIs available in Mexico.76 They should be administered 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast at the standard dose regimen once a day and 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast and dinner at the double-dose regimen.19,20,75 Several studies suggest that genetic differences in the CYP2C19 isoenzyme metabolism can affect the response to PPIs. However, the usefulness of a genetic test for identifying rapid or slow metabolizers is not recommended in daily practice. When this condition is suspected, switching to rabeprazole or ilaprazole, PPIs that do not rely on CYP2C19 for their primary metabolism, is suggested.77

Recommendation 12. On-demand therapy in NERD and mild esophagitis (LA classification A and B) and continuous PPI use in severe esophagitis (C and D) are the most effective regimens for maintenance treatment in GERD. Employing the minimum dose needed to control symptoms and maintain cicatrization of the esophagitis is recommended.

GERD is a chronic recurrent disease, and so requires maintenance treatment. In cases of NERD or mild esophagitis (LA classification A and B), on-demand treatment (the PPI is taken only when there are symptoms and suspended when they disappear) has been shown to be the most cost-effective regimen, compared with intermittent or continuous treatment.19,20,75,78 The recurrence of esophagitis in severe EE is above 80% at six months, therefore, PPIs should be used continuously in those cases.79 Utilizing the minimum PPI dose necessary is recommended for controlling symptoms and maintaining esophageal cicatrization. This strategy reduces costs, as well as the possible appearance of adverse effects related to PPIs.19,20,75

Numerous adverse effects have been related to PPI use, but the large majority have been the product of association, rather than causality studies. Only a greater risk for enteric infections has been established, with respect to PPI use.80

Potassium-competitive acid blockersRecommendation 13. P-CABs are drugs of choice in the treatment of GERD. A standard dose for four weeks is recommended in NERD and for eight weeks in EE, in both mild and severe forms. Half of the dose of the P-CAB can be used in maintenance, on-demand, or continuous treatment.

P-CABs, recently introduced in Mexico, are a new therapeutic class of antisecretory drugs with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic advantages over PPIs. They do not require activation, are super-concentrated in the acid space of the parietal cell, they bind competitively and reversibly to the potassium (K+) binding site of the proton pump, they have a half-life in plasma up to four-times higher than that of PPIs, and they produce complete acid inhibition from the first dose. Thus, they are faster-acting, stronger drugs, whose dose is food-independent, and they raise the intragastric pH above four from the first dose, lasting for 24 hours.81–83 Revaprazan, vonoprazan, tegoprazan, and fexuprazan have been tested and approved for clinical use in Asian countries.82,83 Only tegoprazan is available in Mexico. The clinical trials on these agents conducted in Asian countries and the United States have shown that P-CABs are not inferior to PPIs in the treatment of mild EE and are superior to PPIs in the cicatrization of severe esophagitis (LA classification C and D).84,85 Tegoprazan has been shown to be faster and more effective than placebo in controlling heartburn in NERD.86 P-CABs have been shown to effectively control nocturnal symptoms in GERD.86 In maintenance treatment in erosive GERD, half-dose P-CABs have been superior to PPIs.84,85 P-CABs have also been shown to be effective in on-demand treatment in nonerosive GERD. Therefore, in countries where they are available, P-CABs can be considered first-line drugs in the treatment of GERD. The standard dose (tegoprazan 50 mg daily) for four weeks is recommended in NERD and for eight weeks in mild or severe EE. Half of the standard dose is recommended in both on-demand and continuous maintenance therapy.87–89

In clinical trials and post-market clinical follow-up, P-CABs have shown a safety profile similar to that of PPIs, reporting no severe adverse effects attributable to them.82–86

Adjuvant treatments in gastroesophageal reflux diseaseRecommendation 14. Antacids, alginates, and mucosal protective agents can be used in combination with antisecretory drugs to relieve symptoms caused by GERD. H2RAs can be used for short periods (two weeks) in case of nocturnal symptoms that are not controlled with PPIs. Prokinetics are only indicated in patients with GERD and symptoms suggestive of delayed gastric emptying (satiety, fullness).

Antacids in GERD are used exclusively for the transitory relief of GERD symptoms; they should not be used for chronic treatment. Alginates are useful for preventing reflux from the acid pocket and can be useful, particularly in patients with postprandial or nocturnal symptoms or with HH.19,20,75 The mucosal protective device, Esoxx-One® (Alfa Sigma, Mexico City, Mexico), a bioadhesive formulation based on chondroitin sulfate and hyaluronic acid, when combined with a PPI, has been shown to improve symptoms in patients with nonerosive GERD.90 H2RAs control nocturnal acid breakthrough in patients with GERD treated with a double-dose PPI. Due to the tachyphylaxis or tolerance associated with H2RA use, they are recommended for only short periods of time, between two and four weeks. Prokinetics combined with PPIs are not better than PPIs alone in the treatment of GERD. Their indication is restricted to patients with GERD with symptoms of gastroparesis, such as nausea, vomiting, and early satiety. The G-protein-coupled receptors for gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) reduce the number of TLESRs. Baclofen, when combined with a PPI, has been shown to improve prominent burping and regurgitation symptoms in patients with GERD that are nonresponders to monotherapy with PPIs. Its adverse effects on the central nervous system (dizziness, confusion) limit its use.19,20,75

Medical treatment of nonerosive gastroesophageal reflux diseaseRecommendation 15. In patients with NERD, initial treatment with a standard dose of PPI or P-CAB for four weeks is recommended. For maintenance therapy, we recommend an on-demand or intermittent regimen at the minimum dose of PPI or P-CAB needed to control symptoms.

The treatment goal in NERD is symptom control. PPIs are the drugs of choice, by providing greater symptom relief, compared with H2RAs and placebo.91,92 PPIs produce complete symptom relief in 50-60% of patients with NERD.91–93 The elevated frequency of patients with heartburn included in NERD could explain the lower response rate to PPIs, compared with other phenotypes of GERD. At the adequate dose, symptom response rates are similar among all PPIs.76,94,95

P-CAB pharmacodynamic characteristics offer a useful profile for initial treatment of NERD. As the first treatment option in NERD, P-CABs provided symptom improvement in 66.7% of patients; in patients that persisted with symptoms after eight weeks on PPIs, 53.8% had improvement.96

Two-thirds of patients with NERD that are responders to PPIs present with symptom relapse upon suspending treatment.79 On-demand or intermittent therapy with PPIs or P-CABs can be considered for treating symptoms in those patients. In a clinical trial controlled with on-demand omeprazole, 83% of patients presented with symptom remission at six months.97 In a systematic review that compared on-demand therapy with placebo, in patients with NERD, the days without symptoms were similar to those achieved with continuous therapy.78 In a clinical trial that compared tegoprazan with placebo, with respect to NERD symptom control, there was an increase in symptom-free days.86 In patients with NERD, the preliminary data of a phase 2 clinical trial that compared vonoprazan with placebo showed that said P-CAB was efficacious and safe for controlling symptoms in on-demand treatment.98

Thus, continuous therapy and on-demand therapy with the two classes of therapeutics have similar response rates and both are superior to placebo.

High PPI doses increase costs and have been associated with complications, albeit there is no direct evidence of a causal relation between PPI use and those adverse events.99–101 A reduced PPI dose in GERD is effective in the majority of patients. In a trial on patients with GERD, in whom high PPI doses were utilized, the dose was reduced in 80% of the patients. They had no symptom recurrence and no need to again increase the PPI dose.102

Medical treatment of erosive gastroesophageal reflux diseaseRecommendation 16. In patients with EE, we recommend initial treatment with a standard dose of the PPI or P-CAB for eight weeks. In cases of severe esophagitis (LA classification C or D) a double-dose PPI for eight weeks should be used. For maintenance treatment of mild esophagitis (LA classification A and B), we recommend an on-demand regimen with a standard-dose PPI or half-dose P-CAB. In severe esophagitis, continuous maintenance treatment with the standard-dose PPI or half-dose P-CAB should be used.

PPIs and P-CABs are first-choice antisecretory drugs in EE.20 Using the standard dose, once a day for eight weeks, is recommended for symptom control and endoscopic cicatrization of lesions in more than 80% of cases. Double-dose use is recommended in patients that are nonresponders to treatment with the standard dose and in cases of severe esophagitis (LA classification C and D). P-CABs have shown a faster, stronger, and longer lasting acid-inhibiting effect.83,103,104 Significant differences have not been shown between PPIs and P-CABs, with respect to reflux symptom control.83,96,103–106 However, P-CABs appear to be more effective than PPIs, regarding the healing of esophageal erosions, with statistically significant differences, albeit with marginal clinical differences that tend to equalize over time.83,104 Expert consensuses and recommendations place P-CABs as an option equivalent to PPIs in mild esophagitis and as the best pharmacologic alternative for severe esophagitis.96,106–108

The majority of patients with EE require long-term treatment. In such cases, PPIs should be administered at the lowest dose that efficaciously controls symptoms and maintains healing in esophagitis due to reflux.20,109 P-CABs have been proposed as first-line treatment for that purpose, mainly when the esophagitis is severe.85,110

Medical treatment of Barrett’s esophagusRecommendation 17. Screening for BE is recommended in populations with risk factors and symptoms of GERD. The risk factors include male sex, White populations, age above 50 years, history of smoking, history of chronic GERD symptoms (symptoms at least once a week for more than five years), history of erosive esophagitis, presence of central obesity, and family history of BE or EAC.

BE is considered a precursory lesion to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), and clinical guidelines currently recommend screening for it, in populations with risk factors.111 A meta-analysis that included 49 studies and 307,273 individuals showed that, in patients with reflux and at least one risk factor, the prevalence of BE was higher than in patients with no reflux symptoms (12.2% vs 0.8%). The presence of risk factors was also associated with the presence of BE: family history (23.4%); male sex (6.8%); age > 50 years (6.1%), and central obesity (1.9%).112

Some of the current guidelines propose limiting screening to patients with at least three risk factors, but those authors recognize this is based on expert recommendations and that its strict implementation has negatively impacted EAC screening.113 Thus, limiting screening to the presence of reflux or to a specific number of risk factors is recognized to possibly decrease the timely detection of BE. A study that evaluated cohorts of patients with EAC in the United States (n = 663) and the United Kingdom (n = 645) showed that 54.9% and 38.9% of the patients, respectively, did not meet the screening criteria.114 Thus, screening patients with risk factors and reflux symptoms to opportunely detect BE is proposed.

Recommendation 18. Patients with BE should have continuous treatment with a PPI and remain in a surveillance program.

Different observational studies have shown that chronic PPI use reduces the progression of dysplasia and the appearance of EAC in patients with BE.34

The meta-analysis by Singh et al., with data from seven studies and 2,813 patients, showed a reduction of progression in 71% of the patients using a standard-dose PPI (OR 0.29; 0.12-0.79).115 Nevertheless, there is currently no consistent evidence on the effect of higher PPI doses on oncogenesis, and increasing the dose is only recommended for controlling symptoms and in patients that are candidates for endoscopic eradication therapy.34,113

The detection of dysplasia is the main goal of follow-up in patients with BE and no dysplasia.34 The majority of the current clinical guidelines suggest a surveillance interval of three to five years for this group of patients, but the most recent clinical guideline suggests considering the maximum extension of BE in deciding on the interval, increasing it in patients with BE > 3 cm.113

Overlap with gastroesophageal reflux diseaseRecommendation 19. We recommend a thorough clinical evaluation to identify the criteria of dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), for the possible overlap with GERD.

GERD and dyspepsia are highly prevalent, leading to their common coexistence in the same individual, increasing symptomatology and worsening his/her quality of life.116 The prevalence of this overlap varies, depending on the criteria utilized. With the Rome II criteria, prevalence varies from 12-35%, and with the Rome III criteria, it increases to 20-48%.117 However, the overlapping of these two problems is not only due to chance, and pathophysiologic mechanisms explaining this phenomenon have been proposed. Altered gastric accommodation, delayed emptying, and visceral hypersensitivity play a role in producing the reflux symptoms in patients with dyspepsia.118 The mechanism through which the alteration in gastric accommodation influences the creation of reflux is the release of nitric oxide, impacting the region of the LES and promoting an increase in TLESRs.119

Interestingly, the GERD/dyspepsia overlap can lead to a higher risk for organic lesions, compared with patients that have only GERD or only dyspepsia. A study found that the prevalence of peptic ulcer lesions was higher in the GERD/dyspepsia group (4.7%) versus the group with only one of those problems (0.6%) (p = 0.027). The overlapping of GERD with dyspepsia is more frequent in the postprandial distress subtype120 and has a negative effect on the quality of life of those patients. Individuals with GERD/dyspepsia overlap have been reported to seek medical attention more frequently, compared with patients that present only with GERD or only with dyspepsia (16.7 vs 8.5 vs 12.3%). In addition, they miss more days of work (4.3 vs 2.9 vs 0.7%), have greater antisecretory medication use (30.5 vs 16.4 vs 9.4%), and their symptoms are associated with lower scores on the SF36 quality of life scale.121

IBS is very common, as is GERD, resulting in their overlap also being common. Their coexistence has been calculated at a wide margin, ranging from 5 to 30% in open population survey studies. Patients with nonerosive GERD are reported to present with this overlap more frequently, compared with patients that present with the erosive variant (74.3 vs 10.5%). Most likely, this is due to the visceral hypersensitivity that is more frequent in nonerosive GERD and practically universal in patients with IBS.122 The prevalence of this overlap has been identified according to IBS subtypes. A greater prevalence of GERD was found in the diarrhea subtype (40.9%) than in the constipation subtype (32.9%).123 Patients with GERD/IBS overlap have also been shown to have a lower quality of life.124 The presence of IBS in patients with GERD independently predicts worse GERD symptom control compared with patients that do not have said overlap. GERD/IBS overlap occurs due to the elevated prevalence of the two disorders but is also related to the fact that they share pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in producing the symptoms.

Treatment of refractory gastroesophageal reflux diseaseThe persistence of symptoms of GERD despite medical treatment does not necessarily imply the diagnosis of refractory GERD.

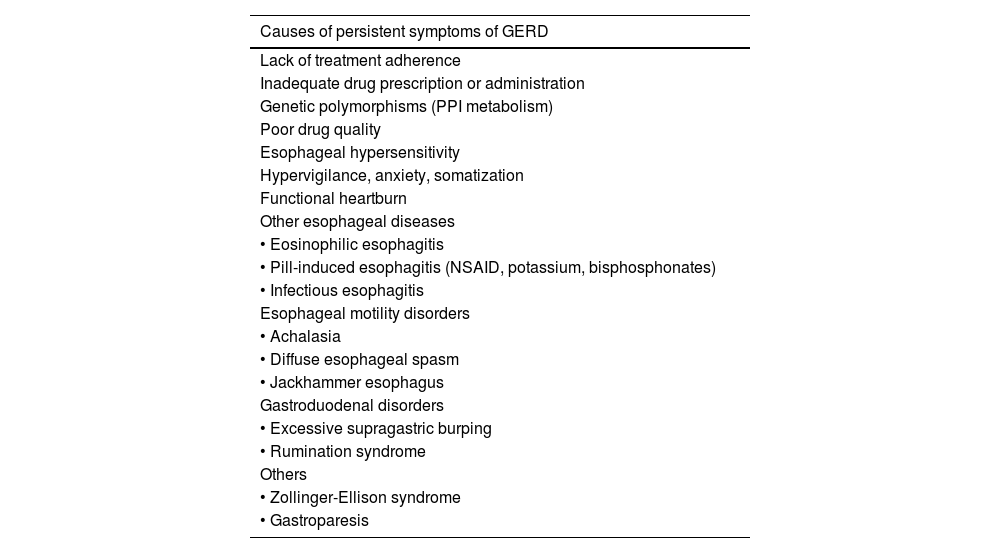

Symptom persistence, despite medical treatment, occurs in 30-40% of patients with GERD.39,125 There are multiple possible causes of treatment failure, especially with PPIs, and they include lack of treatment adherence, inadequate PPI use or administration, pharmacogenetic differences (polymorphisms associated with CYP 450), and incorrect diagnosis, among others (Table 1).125 It is important to recognize these causes and classify patients with “therapeutic failure” into two large groups:

- •

Symptoms of persistent GERD in patients without a previous diagnosis. These are patients who assume they have GERD and have experienced treatment failure, but they are patients that have had no objective evidence of GERD (through endoscopic or physiologic studies). Performing the necessary studies for evidence of GERD, before resuming treatment of these patients, is recommended.39,126

- •

Symptoms of persistent GERD in patients with a previous diagnosis. These patients have objective evidence of GERD (BE, EE, abnormal AET) and are receiving treatment, but their symptoms continue. In such cases, it is important to first review adherence to PPI use and rule out the causes described in Table 1. If the abovementioned causes are ruled out, these cases should be re-evaluated, while they are taking PPIs.39,126

Causes of persistent symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

| Causes of persistent symptoms of GERD |

|---|

| Lack of treatment adherence |

| Inadequate drug prescription or administration |

| Genetic polymorphisms (PPI metabolism) |

| Poor drug quality |

| Esophageal hypersensitivity |

| Hypervigilance, anxiety, somatization |

| Functional heartburn |

| Other esophageal diseases |

| • Eosinophilic esophagitis |

| • Pill-induced esophagitis (NSAID, potassium, bisphosphonates) |

| • Infectious esophagitis |

| Esophageal motility disorders |

| • Achalasia |

| • Diffuse esophageal spasm |

| • Jackhammer esophagus |

| Gastroduodenal disorders |

| • Excessive supragastric burping |

| • Rumination syndrome |

| Others |

| • Zollinger-Ellison syndrome |

| • Gastroparesis |

NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Refractory GERD is defined as the objective evidence of GERD (EE or abnormal exposure to esophageal acid and/or elevated numbers of reflux episodes in MII-pH), despite medical therapy utilizing a double-dose PPI for eight weeks.

Even though the majority of patients with persistent symptoms of GERD, despite medical treatment, are taking the standard-dose PPI, the strict diagnosis of refractory GERD means that the patient has taken a double-dose PPI for at least eight weeks.39,126–128 This definition comes from consensuses and expert groups, but its cost-benefit is actually unknown. Based on that definition, there are physiologic parameters currently obtained during MII-pH in patients on double-dose PPIs that predict the response to treatment of refractory GERD. The most important study is the one by Gyawali et al. that reported an AET > 0.5% and > 40 reflux episodes, detected through impedance, as parameters that can predict response to surgical treatment in up to 79% of patients with refractory GERD, especially if the persistent symptom is regurgitation.38

Recommendation 20. We recommend antisecretory treatment optimization in patients with refractory symptoms of GERD, through the following strategies: a) treatment adherence and appropriate PPI dose in relation to foods; b) double-dose PPI; c) different PPI; d) switch from PPI to P-CAB; and e) adjuvant treatment.

Conventional PPIs (omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole), in general, are acid-labile molecules. They have an enteric covering that prevents their rapid degradation in the stomach, so they can then be absorbed in the distal small bowel.129 Therefore, they are recommended to be taken on an empty stomach, given that the presence of food would delay gastric emptying and provide a greater probability of their degradation. Multiple pharmacokinetic studies have shown that foods reduce their potency between 50 and 70%.130 In addition, PPIs conventionally irreversibly inhibit acid secretion, and so do not block the synthesis of acid resulting from the production of new proton pumps. These pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations provide indirect evidence that underlines the importance of optimum adherence to dose and intake before meals of conventional PPIs. Importantly, there are pharmacologic modifications to PPIs (dual delayed-release formulations, such as dexlansoprazole) or PPIs with longer half-lives, such as ilaprazole, which can do away with the need to strictly take the medication on an empty stomach. Nevertheless, the recommendation is to take all PPIs in a fasting state.

The physiologic parameter used as the surrogate marker of PPI potency, is the elevation of intragastric pH above 4. In addition to their pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic properties, it is important to remember that PPIs are metabolized through the CYP450 metabolic pathway and that there are genetic polymorphisms that determine whether this metabolism is slow, intermediate, fast, or ultrafast. These factors can predict the clinical response to PPIs.

If the half-life in plasma of the drugs is extended, if the individual pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability is reduced, if the speed of action is increased, and if absorption is independent from food, then PPIs will perform better.131 Thus, choosing a PPI that offers those benefits, such as rabeprazole, dexlansoprazole, and ilaprazole, in cases of refractory GERD, can be an option. For example, Fass et al. evaluated the efficacy of dexlansoprazole in 142 patients with refractory GERD.132 After a six-week selection period, the patients switched to dexlansoprazole 30 mg or placebo, for an additional six-week period. The authors reported that, after the change, heartburn was controlled in 88% of the cases. Another study showed that the use of 20 mg of ilaprazole, in patients with NERD and reflux hypersensitivity, was effective for improving symptom scores, histopathologic findings, and inflammatory biomarkers.133

Other ways to optimize PPI performance is to divide or double the PPI dose. For example, a divided dose of 20 mg of esomeprazole twice a day, instead of 40 mg once a day, improves acid suppression.134 This strategy can be useful when there are nocturnal symptoms. Several studies have reported on doubling doses. A Japanese study on patients that did not respond to the standard dose of rabeprazole had significant improvement upon doubling the dose (74 vs 45%, p < 0.001).95 In a recent meta-analysis of 25 studies that included 592 subjects that received PPI therapy twice a day, the standard dose of 40 mg of pantoprazole taken twice a day maintained the intragastric pH > 4 in an average of 68% of cases on day 3 and 40 mg of esomeprazole twice a day maintained the gastric pH > 4 in an average of 88% of patients.135

P-CABs are effective drugs in the management of refractory GERD. Several studies show the usefulness of vonoprazan in this condition.136,137 A study on 124 Japanese patients reported that 20 mg of vonoprazan normalized esophageal exposure to acid in up to 46% of patients and improved symptoms and mucosal healing, compared with PPIs.136 A study evaluating tegoprazan showed that 50 mg of the drug significantly improved nighttime reflux symptoms and sleep quality, compared with 40 mg of esomeprazole.138 Without a doubt, P-CABs are rationally a good option, as long as symptoms are related to esophageal acid exposure.

Adjuvant treatment, such as antacids, alginates, and H2RAs, can be concomitantly used with PPIs in refractory GERD (se recommendation 14).

Recommendation 21. Patients with persistent or treatment-refractory symptoms of GERD should be studied through ambulatory reflux monitoring to identify overlap with esophageal functional disorders.

The persistence of GERD symptoms, despite medical treatment, is well recognized and estimated to occur in 54.1% of PPI users.139 The reasons for symptom persistence are complex and heterogeneous. Factors associated with the continuing of symptoms despite treatment at standard-dose or double-dose PPIs are the presence of atypical symptoms, a longer time presenting with GERD symptoms, symptom severity, and lack of adherence to lifestyle modifications and treatment.140 However, there are other well-known factors for this symptom persistence, when there is good treatment adherence, and one that stands out is visceral hypersensitivity.60 It can be related to sensibilization by previous inflammatory stimuli that lead to an increase in ionotropic purinergic receptors, transient vanilloid receptors, and acid-sensitive ion channels capable of inducing hyperalgesia.141,142 Greater sensitivity to chemical as well as mechanical stimuli has also been found.143 Lastly, another study analyzed the prevalence of esophageal functional disorders in patients with confirmed or unconfirmed evidence of GERD and found that 76% of subjects without GERD had persistent heartburn, despite medical treatment (functional heartburn). Two-thirds of the subjects with symptom persistence and GERD also presented with criteria for functional heartburn, and the remaining subjects had reflux hypersensitivity.144 Therefore, patients with symptom persistence, despite medical treatment, should be studied, to corroborate the presence of GERD as the cause of symptom persistence or to opportunely detect sensitive-sensory disorders as an explanation for the symptoms in those patients (Figs. 3 and 4).

Recommendation 22. We recommend suspending antisecretory treatment and using neuromodulators and psychologic therapies in patients with functional heartburn. In cases of hypersensitivity to acid or the overlap of GERD with functional disorders, we recommend optimizing antisecretory treatment and the concomitant use of neuromodulators and psychologic therapies.

Reflux symptom persistence can also be due to esophageal hypersensitivity and hypervigilance, and so it is thought that central and peripheral sensibilization mechanisms are involved and are correlated with the stress response, as well. In such cases, visceral analgesics, e.g., tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), or trazodone, can be of help, particularly for preventing the unnecessary use of high-dose acid inhibiting therapies in patients diagnosed as PPI-refractory.145 Citalopram 20 mg/day,146 venlafaxine 75 mg/day,147 amitriptyline 12.5-25 mg/day,148 and sertraline 50 mg/day have been used.149 An empiric focus suggested by Scarpellini et al. could be the association of a SSRI (citalopram or fluoxetine) with a standard-dose PPI in the morning.150 When these drugs are prescribed, it is important to explain their adverse effects and the fact that their clinical efficacy can take two to four weeks to appear. Behavioral cognitive therapy and hypnosis are the psychologic therapies that have been shown to be the most useful in the management of patients with functional heartburn and acid hypersensitivity, as well as in the overlap of those disorders with GERD.19,20

Treatment of extraesophageal manifestationsRecommendation 23. We recommend double-dose PPI treatment for 12 weeks in patients with extraesophageal manifestations and objective evidence of GERD.

Patients that present with atypical reflux symptoms (cough, laryngitis, and asthma), accompanied by typical symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation) modestly benefit from empiric management with PPIs at the standard dose for at least eight weeks, as long as there are no alarm symptoms.17 Recent guidelines and consensuses suggest using double-dose PPI for eight to 12 weeks as the first strategy in those patients.17,19 It is clear that a PPI twice a day is superior to a PPI once a day in suppressing gastric acid and most likely more effective for extraesophageal symptoms. In a prospective cohort study, there was a higher response rate (54% higher) in patients that did not respond to standard-dose PPI after eight weeks.151 Regarding prokinetics, limited evidence suggests that their addition could be useful in patients with obesity and/or regurgitation, but not in patients with heartburn.17

It is often assumed that manifestations, such as odynophagia, hoarseness, foreign body sensation (pharyngeal globus), the visualization of an “irritated” larynx, and even halitosis, can be due to GERD. However, there is no evidence that these manifestations are associated with GERD, especially if they present in an isolated manner. In such cases, carrying out objective tests for GERD, before prescribing treatment, is recommended. Frequently, those symptoms (as in other brain-gut interaction disorders) are associated with hypervigilance and visceral hypersensitivity.19,151–154

Endoscopic treatment and surgical treatmentRecommendation 24. We recommend antireflux surgery in patients with objective evidence of GERD, regurgitation as the predominant symptom, large HH, no severe esophageal motility disorder, and no important symptoms of dyspepsia or IBS, performed by an experienced surgeon, in patients that reject long-term medical treatment.

Surgical treatment in patients objectively diagnosed with GERD is as effective as medical treatment with PPIs.155 The best predictors of a favorable response to surgical treatment are positive pH-monitoring and adequate symptom response to a PPI.156,157 Patients with refractory GERD, i.e., those with the persistent EE and abnormal AET after optimum treatment with PPIs or P-CABs, are candidates for fundoplication.158 Every patient that is going to have a fundoplication should undergo HRM to rule out esophageal motility alterations.159 Partial fundoplication is advisable when there is a decrease in the peristaltic reserve.160

Surgery is not recommended in patients with extraesophageal manifestations with no typical GERD symptoms.161 Fundoplication can be useful in a small group of patients, in whom there is objective evidence of reflux as the cause of those manifestations.162 In patients with BE, fundoplication is indicated to control symptoms, even though a recent meta-analysis showed a lower risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia or EAC.163,164 With respect to the type of surgery, no differences have been found between partial or complete fundoplication, in GERD symptom control.165

Magnetic augmentation of the LES, or LINX® (Ethicon Johnson and Johnson, Bridgewater, New Jersey, and Cincinnati, Ohio, USA), is performed by means of a ring-shaped device made of magnets that is surgically placed around the EGJ. This device has been shown to reduce symptoms, AET, and PPI use.166 Magnetic LES augmentation has been successful in controlling regurgitation.167 It produces less abdominal distension, compared with surgical fundoplication,168 and has recently been used in patients with HH larger than 3 cm.169–171 Esophageal erosion or magnetic ring migration have been reported in 0.3% of patients at follow-up at four years.172–174 Incisionless endoscopic fundoplication is useful in a small subgroup of patients with small HH < 2 cm and mild EE (LA classifications A and B).175–181 These procedures are not available in Mexico.

Radiofrequency has been shown to reduce some reflux symptoms, but not AET, nor does it increase LES pressure,182,183 which are reasons for considering it not to be an adequate procedure for treating patients with GERD.184,185

Gastroesophageal reflux disease in special populations: pregnant patients, older adults, obese patientsRecommendation 25. We recommend standard-dose PPI treatment for the control of GERD in pregnant patients.

The incidence of GERD is frequent during pregnancy. This is due to weight gain and the increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Symptoms can start from the first trimester and are more common toward the end of the pregnancy.186 Treatment in this group of patients should be based on the safety of the mother and the fetus, always beginning with nonpharmacologic measures. PPI use is adequate in pregnant women. PPIs are classified as category B drugs, according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with the exception of omeprazole, which is classified as category C. Before starting any medication, the risks and benefits of antisecretory therapy should be carefully discussed.187

Recommendation 26. We recommend the performance of endoscopy in older adults with symptoms of GERD due to the elevated prevalence of more serious disease.

GERD tends to be more severe in older adults due to a lower perception of heartburn. When diagnostic studies are performed on older adults, severe EE is often found, making an early diagnostic approach, regardless of symptom severity, mandatory.188 Xerostomia has been described to reduce protective factors of the esophagus, such as bicarbonate in the saliva, in the older adult. In addition, motility disorders and HH are frequently found in this group of patients.189 Treatment of GERD in the older adult should follow the same guidelines used for younger patients.

Recommendation 27. In the patient with GERD and obesity, who is a candidate for bariatric surgery, we recommend gastrojejunal bypass as the surgery of choice. Sleeve gastrectomy and adjustable gastric banding are not recommended because they are procedures that can worsen GERD by causing reflux.

Laparoscopic fundoplication in the obese patient is safe and feasible, but this group of patients has greater reflux symptom recurrence after the procedure.190–195 Therefore, gastrojejunal bypass or gastric bypass is considered the best operation in the obese patient with GERD.196 Sleeve gastrectomy is a procedure that can cause or aggravate GERD, because of reduced LES pressure due to the disruption of the phrenoesophageal ligament and alteration of the angle of His.197 Esophageal motility alteration and an increase in gastroesophageal reflux have been described after gastric banding. Thus, this technique is not recommended in obese patients with GERD.198

Financial disclosureThe Carnot Laboratory provided the financial support, with respect to logistics, travel expenses, and the face-to-face meeting for all GERD expert participants. No participant received honoraria for formulating these recommendations that are endorsed by the AMG.

Conflict of interestM.A. Valdovinos was a speaker for Carnot, Megalabs, and Bayer.

M. Amieva Balmori was a speaker for Carnot and AstraZeneca.

E. Coss-Adame was a speaker for Asofarma, Carnot, and Grunenthal.

F. Huerta Iga and G. Torres Villalobos were speakers for Carnot.

E.C. Morel Cerda was a speaker for AstraZeneca y Megalabs.

J.M. Remes-Troche was an advisor and advisory board member for Asofarma, Carnot, and Pisa and a speaker for Asofarma, Abbot, Carnot, Chinoin, Johnson and Johnson, Medix, and Medtronic.

J. L. Tamayo de la Cuesta was a speaker for Carnot and Chinoin.

A.S. Villar Chávez was a speaker for Carnot and Asofarma.

L.R. Valdovinos García was a speaker for Carnot, AstraZeneca, Asofarma, and Chinoin.

G. Vázquez-Elizondo was a researcher for Carnot, Chinoin, and Novo Nordisk de México; advisor and advisory board member for Chinoin, M8 Moksha, and Eurofarma; speaker for Chinoin, Asofarma de México, Carnot, and Eurofarma.

R. Carmona, M. González-Martínez, and J.A. Arenas declare they have no conflict of interest.