Cirrhosis of the liver (CL) is a worldwide public health problem, conditioning more than two million deaths annually.1 The only curative treatment for advanced-stage disease is liver transplantation (LT). Today, through improvements in surgical technique and immunosuppression, overall five-year survival surpasses 75%.2

In Latin America, only 18 of the 33 countries perform LT, and annual rates are significantly lower than those of developed countries. Brazil is an exception; not only does its annual LT rate surpass those of its neighboring countries, but it is also one of the three countries worldwide that performs the most transplants. In contrast, Mexico is one of the countries with the lowest LT rates in Latin America and the world, with a rate of 1.8 per one million inhabitants/year,3 despite the fact that, according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI), CL was the fourth cause of death in 2023 in Mexico.4

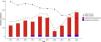

In the decade from 2014 to 2023, the annual LT rate never included more than 300 LTs, as reported by the Centro Nacional de Trasplantes (CENATRA) (Fig. 1). In a country of 126 million inhabitants,5 this underscores the current insufficiency in the number of LTs performed. Historically, 2023 was the year in which more LTs were carried out in Mexico, with a total of 297. Of those LTs, 275 (92.5%) were from cadaveric donors (donors after brain death) and only 22 (7.5%) were from living donors. Importantly, of the total number of procedures performed in that year, 80.5% were carried out at public institutions (Table 1).6

The number of liver transplants from deceased donors per center in 2023.

| Institution | Number of transplants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital General de México Dr. Eduardo Liceaga | 60 | 20.2% |

| Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” | 52 | 17.5% |

| UMAE Hospital de Especialidades “Dr. Antonio Fraga Mouret” del Centro Médico Nacional La Raza | 27 | 9.1% |

| UMAE Hospital de Especialidades Núm. 25 | 27 | 9.1% |

| Operadora de Hospitales Ángeles S. A. de C. V. | 26 | 8.8% |

| Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad Hospital de Pediatría del Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente, Guadalajara, Jalisco | 23 | 7.7% |

| Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad Doctor Gaudencio González Garza Centro Médico Nacional La Raza | 12 | 4.0% |

| Hospital Infantil de México “Federico Gómez” | 11 | 3.7% |

| Centro Médico Naval | 10 | 3.4% |

| Centro Médico Zambrano Hellion | 9 | 3.0% |

| Other centers | 40 | 13.5% |

| Transplants from deceased donors | 275 | 92.5% |

| Transplants from living donors | 22 | 7.5% |

| Total* | 297 | 100% |

UMAE: Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad (Advanced Specialty Medical Unit).

LT recipient outcomes in Mexico are similar to those of other countries,7 but despite the economic and survival benefits of LT, compared with the care of the natural history of the disease,8 the number of patients on the national waitlist is not proportional to the magnitude of the problem. This may be secondary to a deficit in the rate of referrals to a transplantation center by the treating medical personnel due to either a lack of awareness about the benefits to the patient and healthcare system or to misinformation regarding the referral process. This is reflected in the number of transplant centers that are not utilized in the country. According to the CENATRA, there are fewer than 84 authorized transplantation centers. However, in 2023, only eight institutions carried out over 10 transplants per year, the majority of which were centers located in the largest cities of the country, such as Mexico City (68.3%), Monterrey (14.8%), and Guadalajara (14%), among others (Table 1).6 This illustrates the need to make the referral process easier, as well as to decentralize it.

Another limitation to address is the low rate of organ donation. According to the CENATRA, Mexico has one of the lowest donation rates, per million inhabitants, in Latin America and the world.3,6 In 2023, there were only 300 liver donors, despite the fact that there are over 400 registered organ donation-participating hospitals. This deficiency is multifactorial and may be due to a lack of organ donation promotion, perhaps tied to cultural or religious aspects, as well as to the low investment of resources in transplantation programs. The use of extended criteria donors is also an area of opportunity. For example, in the absence of long cold ischemia time, recipients in critical condition (in intensive care), large grafts in small recipients, and donors < 40 years of age with diabetes, using grafts from donors with steatosis > 30% results in acceptable 30-day and 5-year graft survival rates.9 This is particularly relevant in the context of the growing obesity pandemic that will culminate in an increase in the incidence of CL, as well as in a scarcity of ideal donors.10

The assumption could be made that the national needs for LT are covered, given that the donation and transplant rates are close to the number of patients on the waitlist. However, the problem lies in the fact that none of those figures correctly reflects the magnitude of the current problem, which is that CL is the fourth cause of death at the national level. In order to improve this situation, more patients must be included on the waitlist, simultaneously procuring and transplanting livers in said patients, to positively impact mortality due to CL. This involves making the process of referral to a transplant center easier and increasing the number of transplants performed at each center, in a decentralized manner. Thus, increasing human and economic resources will be necessary, not only at the transplant centers, but also at the donation centers. During the process, it will be important to determine and document the factors that have a negative influence on donation and address them. Lastly, to increase the number of transplantations, the use of marginal organs in low-risk recipients can be increased, as reported in recent publications.

Mexico has one of the lowest LT rates in Latin America and currently faces the challenges of a lack of human and economic resources, together with the centralization of services and the scarcity of organ donations. To positively impact mortality due to CL, systematic changes at all levels of healthcare are needed, including significant investment, the decentralization of services, and greater promotion of organ donation.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe present article describes no personal patient information or interventions, and so is considered low risk and requires no approval by the local ethics committee.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.