Acute appendicitis is the most frequent acute surgical illness in the adult. Typical symptoms include: periumbilical pain that migrates to the right iliac fossa, anorexia, fever, and signs of peritoneal irritation.1 Due to the variety of appendicular positions, one third of the patients with acute appendicitis have pain that is located outside of the right lower quadrant. Left side pain is rarely observed.2 In both children and adults, the left cecal appendix can present in situs inversus totalis or in intestinal malrotation.

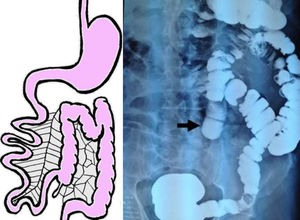

A 49-year-old man had a history of morbid obesity, laparoscopic gastric band placement, and pulmonary thromboembolism 7 years earlier. He came to the emergency service complaining of 24-h progression of sudden, colicky, generalized abdominal pain predominantly in the left lower quadrant, abdominal distension, nausea, and pasty stools. Physical examination showed him to be afebrile, dehydrated, with important abdominal distension, reduced peristalsis, involuntary muscle resistance, and pain upon palpation and decompression of the left iliac fossa. His biochemical parameters were: leukocytes of 9.7 103/ml, neutrophils of 70%, hemoglobin of 17.2g/dl, hematocrit of 52.7%, and platelets of 449 103/ml. Blood chemistry, serum electrolytes, and urinalysis were normal. Initial diagnostic suspicion was diverticular disease. An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed a probable sigmoid volvulus vs colonic malrotation. A barium enema was then carried out that confirmed colonic malrotation (fig. 1). In a new analysis of the tomography scan, acute appendicitis was identified (fig. 2), with a delay in the diagnosis and treatment of approximately 8hours. Laparoscopic appendectomy was performed, washing the abdominal cavity and placing drains. The findings were perforated appendicitis in the left iliac fossa and generalized purulent peritonitis. The patient's progression was adequate and he was released from the hospital on the 4th postoperative day. The histopathologic study confirmed perforated acute appendicitis.

Whereas appendicitis is the abdominal pathology that most commonly requires surgical intervention, intestinal malrotation in the adult is rare. Gastrointestinal tract rotation and fixation abnormalities are frequently associated with abdominal wall anomalies and diaphragmatic hernia. Filston and Kirks3 reported an association with lesions, such as atresias and upper gastrointestinal tract stricture, intussusception, and Hirschsprung disease, of up to 62%.3,4

Intestinal malrotation is an anatomic variant defined as the lack of rotation or incomplete rotation of the intestine. This is caused by a defective rotation of the middle intestine around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery, between weeks 4-12 of fetal life, and the subsequent abnormal fixation to the parietal peritoneum.5,6 It is a broad term that encompasses a wide variety of abnormalities of intestinal rotation and fixation. This alteration can be asymptomatic throughout the patient's lifetime or can produce a fatal acute abdomen, if not appropriately diagnosed and treated. The clinical presentation of malrotation is: intermittent colicky pain, vomiting, chronic diarrhea, and malabsorption. In cases of exacerbation of another pathology, the typical symptoms appear, as occurred with our patient.

To understand malrotation it is necessary to be aware of the normal embryonal development of the intestine. During fetal development, the digestive tract is a short and straight tube. This tube then becomes elongated and takes up its orderly and stable arrangement in the peritoneal cavity. This process is known as intestinal rotation and fixation, according to the classic description by Snyder and Chaffin.7,8

To better understand the abnormalities of rotation and fixation, they are grouped according to the stage of development in which they were produced, as follows:

- -

Non-rotation. The small bowel is found in the right part of the abdomen and the colon and cecum in the left part. The distal ileum crosses the midline from right to left to reach the cecum. Our patient had this type of rotation.

- -

Incomplete rotation. This is produced during the final counter-clockwise 180° rotation of the small bowel or the final counter-clockwise 180° rotation of the colon. The intestine is in an intermediate position between non-rotation and the normal postnatal arrangement.

- -

Reversed rotation. The duodenum is in front of the superior mesenteric artery and the transverse colon is behind the superior mesenteric artery.

Different cases of appendicitis with atypical location have been described, and the same as in our case, initial diagnosis is often incorrect, delaying diagnosis and treatment. Abdominal tomography provides sufficient information for the surgical plan. It is not necessary to perform dynamic studies to evaluate intestinal malrotation. The typical tomographic findings in malrotation are: duodenal-jejunal junction on the right side, colon on the left side, and an abnormal orientation of the mesenteric vein and artery.1,2,5,6The treatment options for left-side appendicitis are the same as those in cases of its habitual location, and open or laparoscopic appendectomy can be performed.9 The laparoscopic approach is viable with good results. It is also useful for evaluating the differential diagnoses and resolving different pathologies.9,10 With respect to the treatment of intestinal malrotation, there is still no consensus on the asymptomatic patient.6

Intestinal malrotation in adults is diagnosed incidentally when detected in imaging studies or during the evaluation of another intra-abdominal pathology (as was the case of our patient).1,3,4,9 The diagnosis and treatment of an acute surgical pathology, such as diverticulitis, or in this case, acute appendicitis, should not be delayed.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center in relation to the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Castillo-González A, Ramírez-Ramírez MM, Solís-Téllez H, Ramírez-Wiella-Schwuchow G, Maldonado-Vázquez MA. Apendicitis aguda en un paciente con malrotación intestinal. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2018;83:356–358.