Bilioenteric fistulas are the abnormal communication between the bile duct system and the gastrointestinal tract that occurs spontaneously and is a rare complication of an untreated gallstone in the majority of cases. These fistulas can cause diverse clinical consequences and in some cases be life-threatening to the patient.

AimTo identify the incidence of bilioenteric fistula in patients with gallstones, its clinical presentation, diagnosis through imaging study, surgical management, postoperative complications, and follow-up.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study was conducted to search for bilioenteric fistula in patients that underwent cholecystectomy at our hospital center due to cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, or cholangitis, within a 3-year time frame.

ResultsFour patients, 2 men and 2 women, were identified with cholecystoduodenal fistula. Their mean age was 81.5 years. Two of the patients presented with acute cholangitis and 2 presented with bowel obstruction due to gallstone ileus. All the patients underwent surgical treatment and the diagnostic and therapeutic management of each of them was analyzed.

ConclusionsThe incidence of cholecystoduodenal fistula was similar to that reported in the medical literature. It is a rare complication of gallstones and its diagnosis is difficult due to its nonspecific symptomatology. It should be contemplated in elderly patients that have a contracted gallbladder with numerous adhesions.

Las fístulas bilioentéricas son la comunicación anormal entre el sistema biliar y el tracto gastrointestinal, que ocurre de manera espontánea y en la mayoría de los casos es una complicación rara de la litiasis vesicular no tratada. Pueden provocar consecuencias clínicas diversas que, en algunas situaciones, ponen en peligro la vida del paciente.

ObjetivoIdentificar la incidencia de fístula bilioentérica en pacientes con litiasis vesicular, su presentación clínica, diagnóstico por imagen, manejo quirúrgico, complicaciones posoperatorias y su seguimiento.

Material y métodosAnálisis retrospectivo de pacientes intervenidos mediante colecistectomía en nuestra institución por colelitiasis, colecistitis o colangitis, en un periodo de 3años, en busca de fístula bilioentérica.

ResultadosSe identificaron 4pacientes, 2hombres y 2mujeres con fístula colecistoduodenal, con una edad promedio de 81.5 años; 2pacientes presentaron colangitis aguda y 2obstrucción intestinal por íleo biliar. Todos los pacientes fueron tratados quirúrgicamente. Se analiza el manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico de cada paciente.

ConclusionesLa incidencia de fístula colecistoduodenal fue similar a la reportada en la literatura médica: es una complicación poco común de litiasis vesicular y su diagnóstico es difícil por la sintomatología poco específica. Se debe tener en cuenta en pacientes adultos mayores, en los que se encuentra vesícula biliar escleroatrófica y múltiples adherencias.

Bilioenteric fistulas are the abnormal communication between the biliary system and the gastrointestinal tract that occur spontaneously.1–3 Courvoisier described them in 1890 as a late and rare complication of cholecystitis. Because of their nonspecific clinical presentation, they are divided into 2 types: the non-obstructive type that produce recurrent cholangitis, malabsorption syndrome, and weight loss, and the obstructive type that develop gallstone ileus or Bouveret syndrome, hematemesis, or melena secondary to gallstone erosion through the gastrointestinal wall.3–5

Bilioenteric fistula incidence in patients with gallstones is from 0.15-8% and presents in 0.15-5% of all surgeries of the biliary tract.6–10 The most frequent fistulous tracts in relation to location are: cholecystoduodenal (77- 90%), cholecystocolonic (8-26.5%), choledochoduodenal (5%), and cholecystogastric (2%).11–13

The mechanism of bilioenteric fistula formation is the impact of the stone on Hartmann's pouch, the subsequent inflammatory process, and the formation of adhesions surrounding the gallbladder. Erosion into the gallbladder wall and contiguous organs by the stone causes necrosis and the formation of the fistulous tract.10,11 The process of chronic inflammation of the gallbladder causes atrophy and loss of its function.14 The cholecystoenteric fistulous tract causes the loss of the protective mechanism of the sphincter of Oddi and the oblique insertion of the bile duct into the duodenum, resulting in the passage of the enteric content into the bile duct system.11

In the medical literature, the majority of cases are diagnosed during surgery, because of the nonspecific symptoms of the pathology. Precise preoperative diagnosis is made in only 7.9% of the patients. Patients are hospitalized mainly due to pain in the right hypochondrium, muscle rigidity, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, and mild, moderate, or severe cholangitis.2,9,10

An abdominal tomography scan is the most useful imaging study because of its findings suggestive of pneumobilia and atrophied gallbladder adhered to neighboring organs.12

Surgical treatment consists mainly of dissection of the inflammatory adhesions, cholecystectomy, and fistula resection. There are some reports of successful laparoscopic approach using intracorporeal suturing and endoscopic staplers.9,10,12

The purpose of the following review is to analyze the incidence of bilioenteric fistulas, their location, clinical presentation, diagnosis, surgical resolution, postoperative complications, and follow-up at our hospital center, given that they are an uncommon complication of gallstones.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study was conducted on all patients that underwent laparoscopic or conventional cholecystectomy within the time frame of January 2012 and December 2015 due to symptomatic gallstones, acute cholecystitis, gallbladder empyema, and cholangitis at the General Surgery Service of the Hospital Regional Puebla, Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE), to identify bilioenteric fistula incidence.

The patients included in the study presented with the radiologic finding of pneumobilia in the abdominal tomography scan. The clinical behavior of the bilioenteric fistulas made it possible to distinguish 2 different clinical patterns and the patients were divided into 2 groups: obstructive biliary fistula (Patients No. 1 and No. 2) and non-obstructive biliary fistula (Patients No. 3 and No. 4). As part of the preoperative studies in the patients suspected of presenting with gallstones, routine studies were carried out (complete blood count, blood chemistry, serum electrolytes, coagulation times, and liver function tests). The imaging studies included liver and biliary tract ultrasound and abdominal tomography. Panendoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) were performed in 2 specific cases.

All the patients underwent surgical treatment under balanced general anesthesia, antibiotic therapy, and analgesia. The type of surgical procedure, progression, and postoperative complications were obtained from the medical records and follow-up was carried out on the surviving patients.

ResultsA total of 952 patients underwent cholecystectomy within the time frame of January 2012 and December 2015. The procedures included 876 (92.01%) laparoscopic cholecystectomies, 54 (5.67%) conventional cholecystectomies, and 22 (2.31%) converted cholecystectomies. Of the patients operated on, only 4 (two men and two women) had cholecystoduodenal fistula, representing an incidence of 0.42% (4/952). The mean age of the patients with cholecystoduodenal fistula was 81.5 years (range 73-93 years).

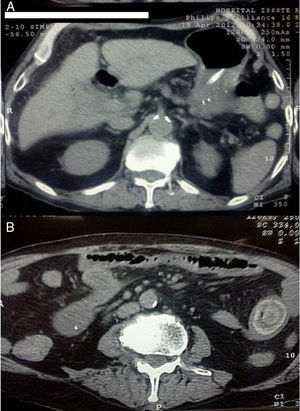

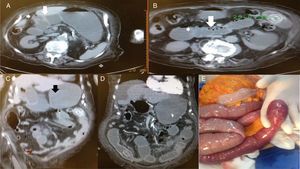

Preoperative characteristicsTable 1 describes the clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and preoperative laboratory and imaging study results of the patients with obstructive and non-obstructive biliary fistulas. The two patients with the obstructive type presented mainly with abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting, and obstipation. In addition, one of the patients had melena and “coffee ground” vomiting and underwent panendoscopy. The laboratory work-up had no significant alterations. In the abdominal tomography scan, those patients had the classic Rigler's triad for gallstone ileus: pneumobilia, atrophied gallbladder, signs of bowel obstruction, and visualization of an intraluminal stone. In one of the patients, stone migration was documented in serial abdominal tomography (figs. 1 and 2). The 2 patients with the non-obstructive type presented with abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant, fever, jaundice, and weight loss of no apparent cause. One of the patients presented with moderate cholangitis (triad of Charcot, low blood pressure, and disorientation) that responded to medical treatment with antibiotics and crystalloid solutions. The other patient presented with severe cholangitis that progressed to multiple organ failure during hospital stay. The laboratory work-up of both patients reported leukocytosis and liver function test alterations.

Clinical, laboratory, and imaging characteristics of patients with cholecystoduodenal fistula.

| Obstructive type | 1 | 2 | Non-obstructive type | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 84 | 93 | Age | 76 | 73 |

| Sex | Man | Woman | Sex | Man | Woman |

| Clinical symptoms | Diffuse colicky abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, constipation, obstipation, 6-day progression | “Coffee ground” vomiting, melena, abdominal bloating and pain, constipation, obstipation, 15-day progression | Clinical symptoms | RUQ abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, asthenia, adynamia, skeletal muscle pain, jaundice, disorientation, low blood pressure, 4-day progression | 4kg weight loss one month prior, RUQ abdominal pain, fever, jaundice, pruritus, choluria, acholia, disorientation, low blood pressure, 72-h progression |

| Comorbidities | None | DM-2, Senile dementia | Comorbidities | DM-2, previous AMI and alcoholism | DM-2, HBP |

| Hemoglobin g/dl | 13.8 | 16.5 | Hemoglobin g/dl | 8.5 | 9.3 |

| Leukocytes (1000/μl) | 8.6 | 8.5 | Leukocytes (1000/μ) | 14.6 | 21.2 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.32 | 0.41 | Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.21 | 8.9 |

| TGO (IU/L) | 23 | 16.5 | TGO (IU/L) | 138 | 530 |

| TGP (IU/L) | 16 | 9.3 | TGP (IU/L) | 92 | 274 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 101 | 195 | Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 142 | 317 |

| Other preoperative studies | None | Upper endoscopy: Intestinal fluid, esophageal lumen and stomach, first duodenal portion with 3cm excavated ulcer | Other preoperative studies | None | ERCP: bile dripping through the papilla, 10mm choledochus, stones in its distal and proximal thirds, the largest 15mm, after sphincterotomy with spontaneous exit of 3 stones |

AMI: Acute myocardial infarction; DM-2: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

HBP: High blood pressure; RUQ: Right upper quadrant.

Patient No. 2 with intermittent bowel obstruction. A) Non-contrasted axial tomography showing the porcelain gallbladder with wall thickening, air inside the gallbladder (small arrow), adhered to the primary portion of the duodenum with its edematous wall (large arrow), and important distention of the rest of the duodenum and stomach. B) Lower axial view showing dilated jejunum segments with edema (small arrow), intestinal pneumatosis (large arrow), and 29mm calcified intraluminal stone. C) Coronal view of the same patient showing pneumobilia, adherence of the gallbladder to the duodenum (white arrow), gastric and duodenal distention (black arrow) proximal to the intraluminal stone in the jejunum and collapse of the distal segments (red arrow). D) Coronal view of serial non-contrasted tomography, 12 days after the previous images. Migration of the stone into the terminal ileum and free fluid in the cavity can be observed. E) Intraoperative image showing bowel obstruction from the intraluminal stone at the level of the ileum, with hyperemia and edema of the intestinal wall.

The ultrasound studies of both patients identified gallstones and porcelain gallbladder. Pneumobilia was observed in the abdominal tomography scan of one of the patients, along with porcelain gallbladder adhered to the duodenum and air inside the gallbladder (fig. 3).

Patient No. 3 that presented with moderate acute cholangitis. A) Axial view of the abdomen showing pneumobilia in the intrahepatic bile duct (white arrow). B) The same patient, axial view, showing the contracted gallbladder, air inside the gallbladder (short arrow), and its adherence to the duodenum (large arrow).

The patient with severe cholangitis was initially suspected to have gallstones and so ERCP was performed. Three stones exited spontaneously after sphincterotomy and the fistulous tract was not identified. The patient's progression was torpid, despite the procedure.

Perioperative characteristicsTable 2 describes the perioperative findings, the surgeries performed, postoperative progression, and follow-up of the surviving patients.

Surgical characteristics and follow-up of patients with cholecystoduodenal fistula.

| No. | Age/ Sex | Preoperative diagnosis | Perioperative findings | Surgery | SD min | Bleeding (ml) | DHS | Morbidity | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 84/M | Gallstone ileus | Intestinal occlusion from impacted stone in the ileum at 1.10m from the fixed segment of Treitz. | Enterolithotomy | 60 | 50 | 5 | None | 21 days after release, asymptomatic, adequate surgical wound cicatrization |

| 2 | 93/F | Gallstone ileus | Free fluid from inflammatory reaction, intestinal occlusion from the stone impacted in the ileum at 1.5m from the fixed segment | Enterolithotomy (fig. 2E) | 75 | 200 | 22 | Surgical wound dehiscence, nosocomial pneumonia followed by sepsis and multiple organ failure | Death at 28 DHS |

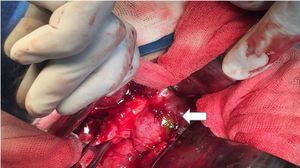

| 3 | 76/M | Mild cholangitis secondary to cholecystoduodenal fistula | Subhepatic adhesions, gallbladder fundus adhered to the fistulous tract that communicates with the duodenum, 2cm duodenal aperture (fig. 4) | Cholecystectomy, fistulous tract resection, primary duodenal closure in 2 layers (fig. 4) | 120 | 300 | 15 | None | 30 days after release, asymptomatic, adequate surgical wound cicatrization |

| 4 | 73/F | Severe cholangitis secondary to unresolved choledocholithiasis | Cholestatic liver, subhepatic adhesions, atrophied gallbladder adhered to the fistula and duodenum, 2cm gallstone was extracted from the fistulous tract (fig. 5) | External diversion of the fistulous tract with Nelaton 18FR catheter | 180 | 150 | 13 | Septic shock secondary to severe cholangitis, multiple organ failure | Death at 14 DHS |

SD: Surgery duration; DHS: Days of hospital stay.

In the 2 patients with obstructive fistula, diagnosis of gallstone ileus was confirmed and both presented with firm subhepatic adhesions, for which they underwent only exploratory laparotomy and enterolithotomy. Due to diagnostic delay, one patient underwent surgery on day 13 of hospital stay.

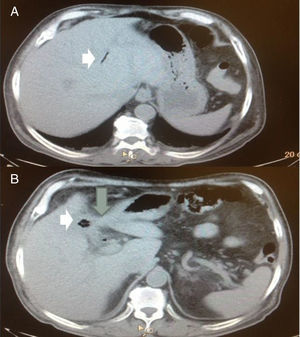

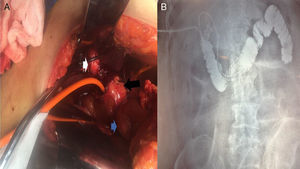

In one of the patients with non-obstructive fistula, with moderate cholangitis, the presence of cholecystoduodenal fistula was confirmed and cholecystectomy was performed with resection of the fistulous tract (fig. 4). The other patient, due to poor clinical progression following endoscopic sphincterotomy, underwent biliary tract exploration and drainage with a Kehr's T tube on the 9th day of hospital stay. A cholecystoduodenal fistula was found, and due to its severity, only external drainage of the fistula was carried out (fig. 5).

A) Intraoperative image of Patient No. 4 that presented with severe cholangitis, showing the porcelain gallbladder (white arrow), which was adhered to the complex fistulous tract (black arrow). The Nelaton catheter was placed inside it, which in turn, communicated with the first portion of the duodenum (blue arrow). B) Fistulography through the Nelaton catheter of the same patient, using water soluble contrast medium carried out 24h after the surgical procedure. The insertion of the catheter that passes through the fistulous tract is observed, adhered to the first portion of the duodenum, reaching the third and fourth portions. After the contrast medium was administered, the duodenal-jejunal junction can be seen up to the fixed ligament of Treitz. The knee and second portion of the duodenum are filled with contrast medium reflux.

After surgery, the patients with the obstructive fistulas tolerated oral diet, channeled gases, and one patient was released on day 5 of hospital stay due to clinical improvement. Unfortunately, the other patient had an exacerbation of senile dementia, remained bed-ridden, acquired nosocomial pneumonia, and died from secondary sepsis on day 22 of hospital stay.

One of the patients with non-obstructive fistula progressed satisfactorily, tolerated oral diet, had no other eventualities, and was released on day 15 of hospital stay. The other patient with severe cholangitis did not improve, despite endoscopic and surgical management, and required surveillance in the intensive care unit with mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, and antibiotics. She died on day 15 of hospital stay, after presenting with septic shock and multiple organ failure.

Follow-upOne of the patients with obstructive fistula and another with non-obstructive fistula had follow-up at the outpatient consultation on days 21 and 30 after their hospital release, respectively. Neither of them showed any alterations.

The correct preoperative diagnosis was made in 3 of the 4 (75%) study patients. Mean surgery duration was 108.75min (range: 60 to 180min), mean blood loss was 175ml (range: 50 to 300ml), and mean hospital stay was 13.75 days (range: 5 to 22 days). The mortality rate was 50%.

DiscussionBilioenteric fistula is a very uncommon complication of gallstones. Its incidence is reported at 0.15 to 8%.6–10 In our study, we found an incidence of 0.42% and all the patients presented with cholecystoduodenal fistula. Another study reported an incidence of 0.29% (12/4,130), and cholecystoduodenal fistula also predominated.2

The mean age of the patients in the present study was 81.5 years and in other studies bilioenteric fistula is more frequent in patients above 60 years of age.2,4 The most frequent bilioenteric fistula symptoms reported by other authors are: pain in the right hypochondrium, jaundice, cholangitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, fat intolerance, diarrhea, and bowel obstruction due to gallstone ileus.2,4,6,10

Abdominal tomography is the imaging study of choice because of its findings suggestive of pneumobilia and porcelain gallbladder adhered to gastrointestinal organs. In relation to gallstone ileus, serial studies identify intraluminal stone, pattern of bowel obstruction, and change of stone position.2,12 In another study, the use of ERCP did not reveal the presence of bilioenteric fistula,2 the same as occurred with one of our patients.

Because of the nonspecific nature of the signs and symptoms of this pathology, preoperative diagnosis is difficult and is usually made during surgery. In one study conducted on 12 patients presenting with bilioenteric fistula, correct preoperative diagnosis was made in only 2 of those patients (16.6%).2 Likewise, the preoperative diagnosis of gallstone ileus was made in only 23-75% of the cases and was made during surgery in more than 50% of the patients.15–18

Surgical treatment of bilioenteric fistulas consists of meticulous dissection of the adhesions, cholecystectomy, and resection of the fistulous tract.2 The therapeutic options for gallstone ileus are: A) one-stage procedure (enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy, and fistula closure in a single surgery) with a mortality rate of 16.9%. B) Enterolithotomy with a mortality rate of 11.7%, but with a risk for gallstone ileus recurrence of 2-8%, considered the best treatment option in patients in poor condition (dehydrated, septic, with peritonitis) that cannot tolerate prolonged surgery duration. C) Two-stage procedure consists of enterolithotomy, followed by cholecystectomy and fistula closure at a 4 to 6-week interval, with minimal mortality.15,16,18–22 In the patients with obstructive fistula in our study, enterolithotomy was considered the best option. Laparoscopy is an option for resolving bilioenteric fistulas and gallstone ileus, reducing hospital stay, and the conversion rate to open surgery is 6.3%.9,23

The mortality rate in other studies for bilioenteric fistula is 15-22% and the causes are: pancreatitis, external biliary fistula, biliary tract lesion, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, diabetic ketoacidosis, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, pulmonary thromboembolism, and bowel obstruction due to adhesions. The mortality rate for gallstone ileus is 1-30% and the influencing factors are: emergency surgery in elderly patients with comorbidities, acute cholangitis, nosocomial infections, acute myocardial infarction, and pulmonary thromboembolism.2,4,16,17 The mortality rate in our study was 50%, caused by the delay in the diagnosis, nosocomial pneumonia, and severe acute cholangitis.

ConclusionsCholecystoduodenal fistula is a complication of gallstones that causes bowel obstruction, cholangitis, weight loss, and other nonspecific symptomatology. Although it is rare, this fistula should be contemplated in elderly patients and in cases of porcelain gallbladder with multiple adhesions.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Please cite this article as: Aguilar-Espinosa F, Maza-Sánchez R, Vargas-Solís F, Guerrero-Martínez GA, Medina-Reyes JL, Flores-Quiroz PI. Fístula colecistoduodenal, complicación infrecuente de litiasis vesicular: nuestra experiencia en su manejo quirúrgico. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2017;82:287–295.