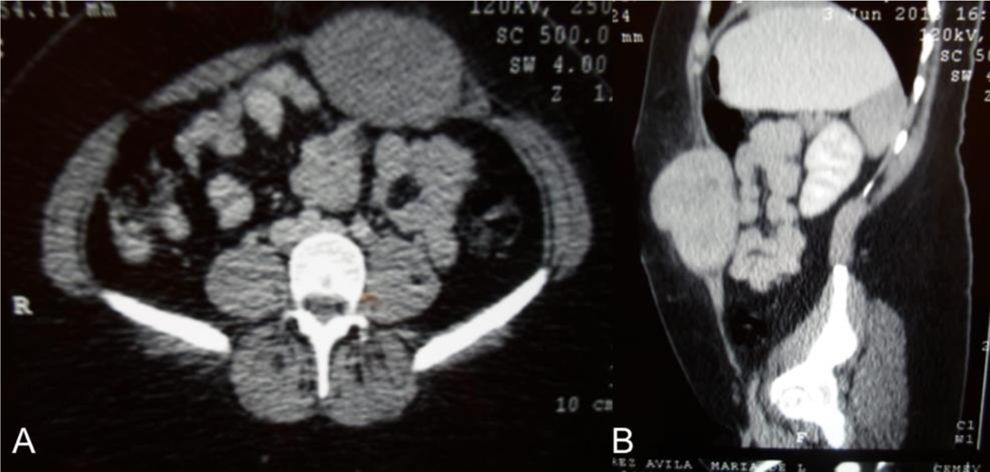

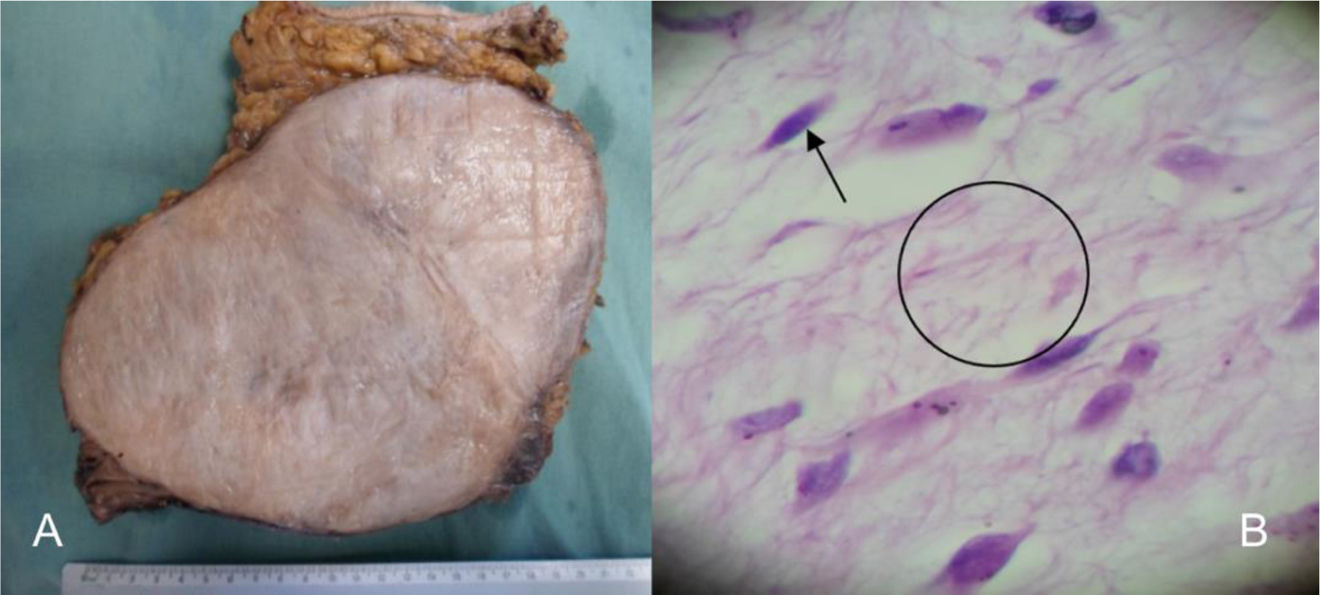

A 27-year-old woman with a family history of breast cancer (mother) initially presented with an abdominal tumor (Fig. 1) that increased in volume. She was programmed for surgical examination and a 15×20cm abdominal tumor that invaded the deep planes, aponeurosis, and muscle was found. Due to the extensive tissue invasion, an incisional biopsy was performed and sent to the oncologic surgery service. Invasion of the abdominal wall involving all layers up to the parietal peritoneum was reported. The tumor was resected with macroscopic tumor-free margins. The definitive histopathologic study confirmed desmoid tumor (Fig. 2).

(A) Macroscopic section of the surgical specimen, showing a solid, well-delimited, light gray tumor. (B) Microscopic image of the surgical specimen, showing fusiform cells that correspond to fibroblasts, cells that make up the cellular component of the tumor (arrow), and surrounding fibrillar structures that correspond to collagen fibers of the stromal content of the tumor (circle).

Desmoid-type fibromatosis is an aggressive benign tumor of mesenchymal origin that has an incidence of 2–4 cases per million inhabitants and accounts for 0.03% of all tumors and 3% of soft tissue tumors. This type of tumor is related to trauma and previous surgery, to radiotherapy, and to increased estrogen levels, as occur in pregnancy. It affects soft tissues, is divided into superficial and deep, and consists of a single entity known as the desmoid tumor. The biologic behavior of desmoid tumors varies and is an intermediate stage between a benign fibroblastic tumor and fibrous sarcoma.1

Tumor etiology is currently known to be either sporadic or hereditary. Close to 90% are sporadic, caused by an activating somatic mutation in the B-catenin-encoding gene (CTNNB1), whose function is to act as an intermediary in the network of cadherins and actin filaments that are responsible for cell adhesion. They present mainly in the limbs, thoracic wall, head, neck and breast.2 On the other hand, close to 10% are hereditary, and are associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and its Gardner syndrome variant. Desmoid tumors related to FAP arise due to inactivation of the APC gene that is found on chromosome 5, resulting in an inability to degrade B-catenin, favoring fibroblast proliferation. The presence of FAP increases the risk of presenting with desmoid tumor by 8–14%.3

Desmoid tumors tend to appear in patients between 15 and 60 years of age, and most commonly around 30 years of age. Women are more prone to develop them, especially after pregnancy, and said incidence decreases after menopause. Reports state that tumors also tend to grow more rapidly in reproductive-age women than in men.4 Clinical presentation is dynamic, from an asymptomatic and indolent mass to a locally invasive mass with varying clinical symptoms, in which increased volume predominates, depending on tumor location.

Ultrasound is commonly utilized as the initial study and is the preferred option for follow-up and guided biopsies in patients with tumors in the limbs or abdominal wall.2 Contrast-enhanced computed axial tomography enables the identification of soft tissue lesions, whether they have well-defined borders or infiltrative margins, as occurs in the abdominal wall or mesentery, respectively. It is the preferred study for the follow-up of intra-abdominal tumors.5 Magnetic resonance imaging is the study of choice in extra-abdominal presentations and in individuals who are allergic to iodine-containing contrast medium.1 Tru-cut needle biopsy is recommended, as is immunohistochemistry, in which the tumor is positive for B-catenin, vimentin, COX2, tyrosine kinase, PDGFRb, androgen receptors, and estrogen receptor beta and is negative for desmin, S-100, h-caldesmon, CD34, and CKIT.6

It is currently recommended to start with a period of active surveillance, unlike previous practice that centered on surgery.6 Progression has been reported to stop within a 14 to 19-month period in up to 50% of cases and 25% of patients experience tumor regression. Progression tends to occur in the first months and is very unlikely after 3 years of follow-up. Only 14–16% of patients require surgery.7 The recommended active surveillance follow-up is with computed axial tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, according to tumor characteristics, every month for the first 2 months, every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months up to the fifth year, and then once a year.

Systemic treatment may be considered in patients that present with progression during the active surveillance period (except in cases of abdominal wall tumors) or in patients that reject that type of follow-up. Anti-inflammatory agents, estrogen blockers, targeted therapies, or chemotherapy may be employed. Surgical intervention is reserved for a small group of patients because these tumors have a high recurrence rate (between 20 and 65% at 5 years) and surgery often requires extensive procedures that can be incapacitating, affecting patient functionality. Currently, it is preferred to leave microscopically positive margins, as long as that is justified for preserving functionality.7

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that this article contains no personal information that could identify the patient, preserving patient anonymity, per institutional protocol. Informed consent was not requested for the publication of this case because no personal or imaging data were published that could identify the patient. This article meets the current bioethical research norm, no experiments were conducted on humans or animals.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.