Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a diagnostic challenge in the pediatric population due to its low prevalence, nonspecific clinical presentation, and heterogeneous biochemical characteristics and imaging results.1 AIP is more common in adolescents, with a slight predominance in males (53%) and a median age at diagnosis of 13 years.2 Despite the fact that it is an uncommon disease in pediatrics, its importance lies in the need for a histologic diagnosis before starting treatment with corticosteroids –a therapy not exempt from risks– and in the importance of preventing underdiagnosis that could delay adequate management.2

The diagnostic criteria established for adults, such as the 2010 International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC) for AIP,3 include serology, histopathology, involvement of other organs, imaging study findings, and steroid therapy response, which may not be fully applicable in the pediatric population, given the variability of clinical manifestations and laboratory findings. In adults, elevated IgG4 levels are essential for diagnosing type 1 AIP (68–92 %), whereas they are observed in only 22% of cases in children.2

From the imaging perspective, AIP can reveal overall or focal parenchymal enlargement, presenting as hypointense areas in T1-weighted images, as well as irregularities in the main pancreatic duct (64%).2 However, none of those clinical or radiologic characteristics are specific for AIP, and so the differential diagnoses of pseudotumor and pancreatic tumor must be considered.4 Unnecessary surgical interventions, such as partial pancreatectomy or Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy, are reported in up to 17% of patients with AIP, underlining the importance of combining numerous diagnostic criteria and considering histopathologic diagnosis the gold standard.5 In such a context, obtaining tissue through ultrasound endoscopy (USE) has emerged as a basic tool, standing out for its high diagnostic yield and safety profile in the adult population.6 USE is the preferred method for pancreatic biopsy because it is less invasive, compared with laparoscopy, and it does not require the ionizing radiation used in computed tomography (CT)-guided percutaneous biopsy.7

A 13-year-old girl presented with recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP), initially of idiopathic etiology, with three episodes of intense abdominal pain in the epigastrium and mesogastrium, accompanied by nausea and vomiting, but no fever or jaundice. During the acute episodes, elevated levels of amylase (340-1,120 U/l) and lipase (285–965 U/l) were detected. CT and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) identified a slight increase in the size of the pancreas, with no other significant alterations.

Etiologic study included measuring the levels of triglycerides, calcium, parathyroid hormone, and serum IgG4, and they were all within normal limits. Likewise, the genetic analysis ruled out the most frequent gene mutations (PRSS1, SPINK1, CFTR, CPA1, and PRSS2) associated with chronic pancreatitis.8 Due to the persistence of recurrent episodes and absence of obvious etiology, USE-guided biopsy of the pancreas was performed to obtain tissue.

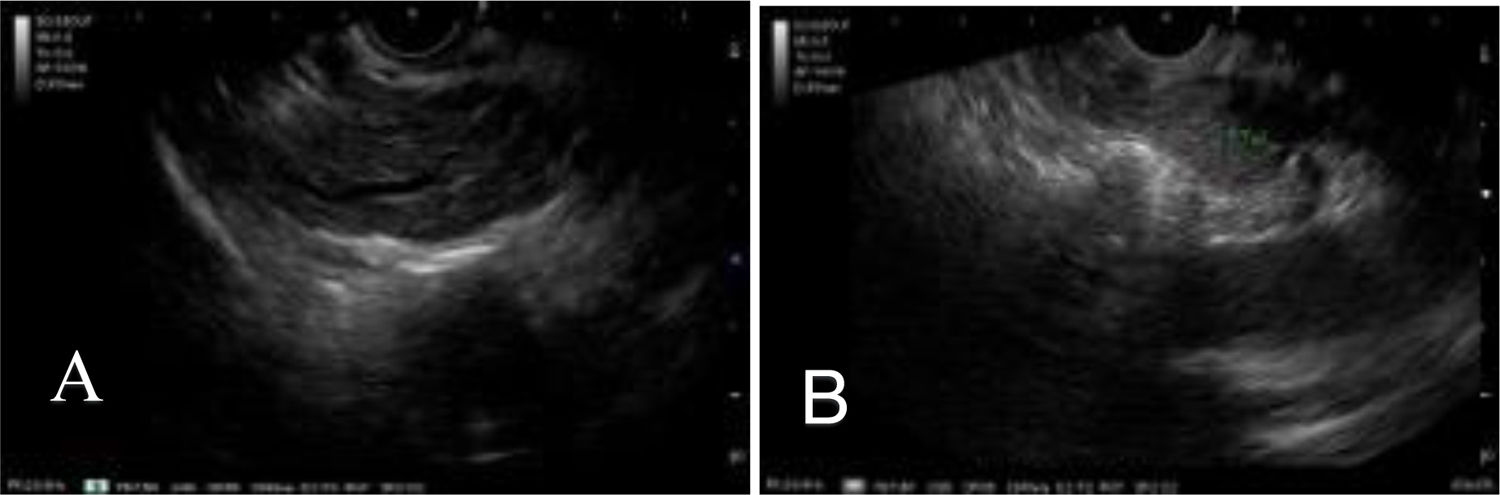

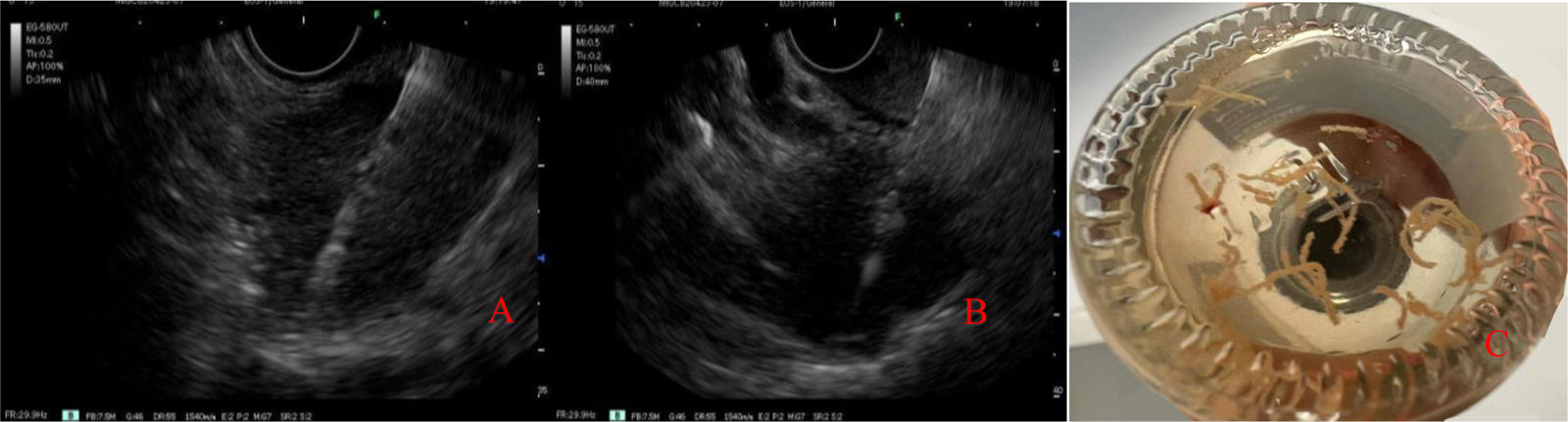

The USE was carried out under general anesthesia, with a linear echoendoscope, enabling detailed evaluation of the pancreatic parenchyma (diffuse enlargement), main pancreatic duct, and contiguous organs (Fig. 1). Using a 22 G Franseen fine-needle biopsy needle, samples were obtained from the head of the pancreas, via the transduodenal approach, and the body of the pancreas, via the transgastric approach, preventing vascular damage through the Doppler technique (Fig. 2). One needle pass was carried out in each region, using the fanning technique, with the slow removal of the stylet to maximize the sample yield (Fig. 2). No intraoperative or postoperative complications were registered.

(A) Body and (B) tail of the pancreas with minor Rosemont criteria for chronic pancreatitis9,10) (hyperechoic traces with no acoustic shadow and hyperechoic enhancement of the walls of the main pancreatic duct).

The histopathologic analysis of the samples revealed lymphoplasmacytic infiltration positive for IgG4, consistent with AIP, emphasizing the usefulness of the minimally invasive approach through USE for diagnostic accuracy, as well as for guiding adequate treatment. Treatment was started with prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) for four weeks, with reduced disease progression for the following month. The patient progressed favorably, with no new episodes of pancreatitis during a 15-month follow-up.

USE is an indispensable diagnostic tool in the context of pediatric AIP because it enables samples to be obtained that are adequate for histopathologic and immunohistochemical analyses. Even though there are challenges related to the availability of trained echo-endoscopists and the necessary infrastructure, the benefits in terms of diagnostic precision and safety profile justify its implementation at referral centers.

In conclusion, AIP should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recurrent pancreatitis in children, especially when clinical and imaging characteristics are inconclusive. USE-guided biopsy of the pancreas is a fundamental diagnostic support enabling histologic confirmation through a minimally invasive procedure, as well as preventing treatment with inadequate therapies that are not exempt from complications and underdiagnosis of the disease.

Ethical considerationsWe declare we obtained written informed consent from the legal guardians of the patient to publish this article. This work is not an experimental or clinical study, but rather the presentation of a relevant clinical case. It contains no personal data that could identify the patient, thus additional consent was not required.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.