Chronic or persistent gastrocutaneous fistulas (GCFs) after the removal of the percutaneous gastrostomy tube are a complication that is difficult to treat, with an estimated incidence of about 4.5%.1 The duration of gastrostomy use (> 6 months) and the resulting epithelialization of the tract are critical factors in the development of GCFs.2–4 Even though the majority of gastrostomy sites close spontaneously in 1 to 3 months,4 some of the fistulas become chronic. Refractory defects continuously release large volumes of gastric content that cause considerable morbidity, with known complications that include cutaneous lesions, the risk for infection, dehydration, electrolyte alteration, as well as the need for frequent dressings and ostomy bags that notably alter quality of life.

The most widespread initial strategy is conservative management to optimize healing, which includes proton pump inhibitors and somatostatin analogues for reducing gastric secretions, prokinetics for increasing gastric emptying, and post-pyloric feeding.5 However, the biggest problem that modality entails, in the majority of cases, is the high anxiety burden, due to the time needed for closure, added to the months that have already gone by since the gastrostomy removal. Therefore, many patients seek an immediate and definitive solution. We present the case herein as a minimally invasive alternative for managing GCFs.

A 70-year-old woman, with a history of hypothyroidism, dyslipidemia, an ex-smoker, and cancer of the larynx treated through radiotherapy and chemotherapy, had to have a percutaneous gastrostomy for enteral feeding. One year and five months after its placement, the patient had to repeatedly have unscheduled consultations due to persistent peristomal leakage and ostomy replacement, together with the discomfort involved. Due to the anxiety caused, social limitations, and acceptable tolerance to oral diet, the patient decided to have the tube removed. Four months after the removal, unmanageable leakage through the ostomy opening persisted, and so the surgical approach was decided upon.

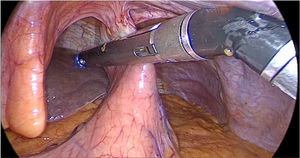

Surgical technique. The patient was placed in the Lloyd Davis position, a 2cm infraumbilical incision was made, and a closed pneumoperitoneum was created, using a Veress needle. Three trocars were placed: a 12mm trocar in the infraumbilical and left flank positions and a 5mm trocar in the right flank. The gastrocutaneous tract was identified, it was resected with a blue cartridge mechanical suture shot, the fistulous remnant located on the anterior abdominal wall was extracted with an energy device, the external tube opening was then resected, through a diamond-shaped excision of the skin, and primary closure was performed with nylon 3-0 separate sutures. The procedure was technically simple, with a duration of 1hour and 30minutes. The patient was released on the following day.

Follow-up was carried out for three months, with no recurrence of the fistula. The patient was immediately satisfied, which is not to be underestimated in this type of condition (Fig. 1).

Even though at first surgery appears to be a more expensive alternative (due to surgery duration and the cost of the mechanical suture device) than the initial measures that are usually carried out (conservative measures, drugs, endoscopic closures, curettage and cauterization, among others), the large majority of those measures result in considerable recurrence events, and their total cost, after adding together the expense of all the procedures, can end up being higher than the cost of an initial surgical approach.

Given the above information, we conclude that the minimally invasive surgical approach for the treatment of persistent GCFs can be implemented as an initial measure in selected cases because it is a safe, rapid, simple, and easily reproducible alternative for the definitive resolution of that anxiety-laden complication.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that the present article contains no personal information that could identify the patient and therefore informed consent from the patient was not required.

This case report meets the current bioethical research regulations and was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires.

Financial disclosureNo specific grants were received from public sector agencies, the business sector, or non-profit organizations in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Masino EE, Calderón Novoa FM, Cano V, Wright F, Duro A. Fístula gastrocutánea: resolución laparóscopica. Rev Gastroenterol Méx. 2022;87:396–397.