Variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is one of the complications of portal hypertension. It is associated with high morbidity and mortality at 6 weeks, in around 15-20% of patients.1 Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) plays an important role in treating said bleeds.2,3 Despite its efficacy and safety profile, the procedure can cause potentially life-threatening bleeding secondary to ulceration, following band ligation.4,5

A 57-year-old woman had a past medical history of diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, and Child B cirrhosis of the liver, with a MELD score of 10. She was diagnosed in 2023, when she presented with her first episode of variceal UGIB.

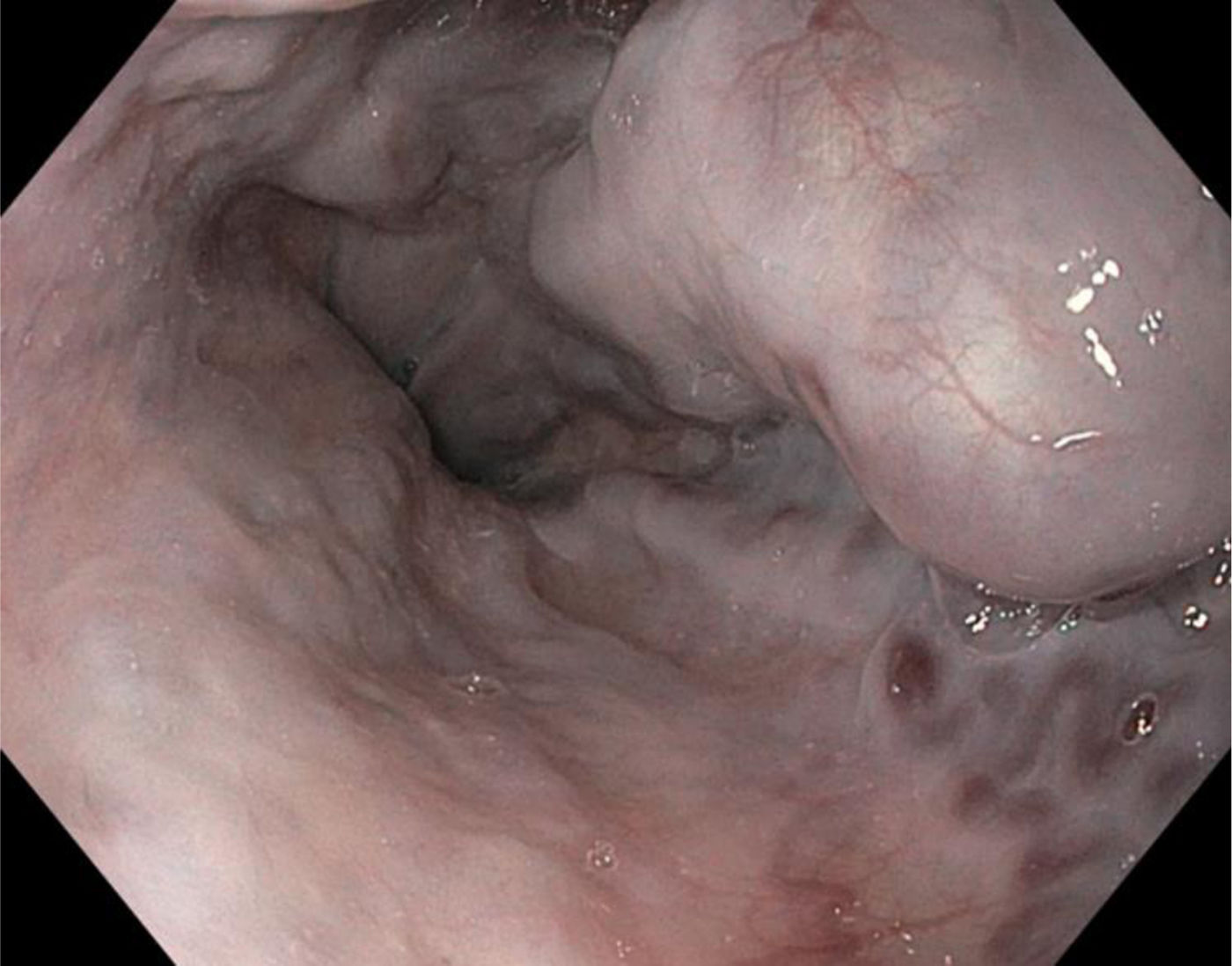

She was admitted to our hospital in June 2024 and programmed for EVL as an outpatient. In the gastroduodenal endoscopy (GDE), 3 large esophageal varices and one medium-sized varix were found. EVL was carried out using 3 elastic bands, with no immediate complications (Fig. 1). Ten days later, the patient arrived at the emergency service, presenting with hematemesis at a volume of 1000 cc, melena, and syncope.

Physical examination revealed that she was hemodynamically unstable, with a Glasgow coma scale score of 14. Laboratory tests showed a decrease in hemoglobin, compared with the previous outpatient control value (from 10.5 to 7.6 g/dl).

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and medical management of the variceal UGIB was started. During the first hours of hospitalization, she presented with a new episode of hematemesis, greater hemodynamic instability, and a decrease in hemoglobin to 5.9 g/dl. She was intubated and vasopressor support was started.

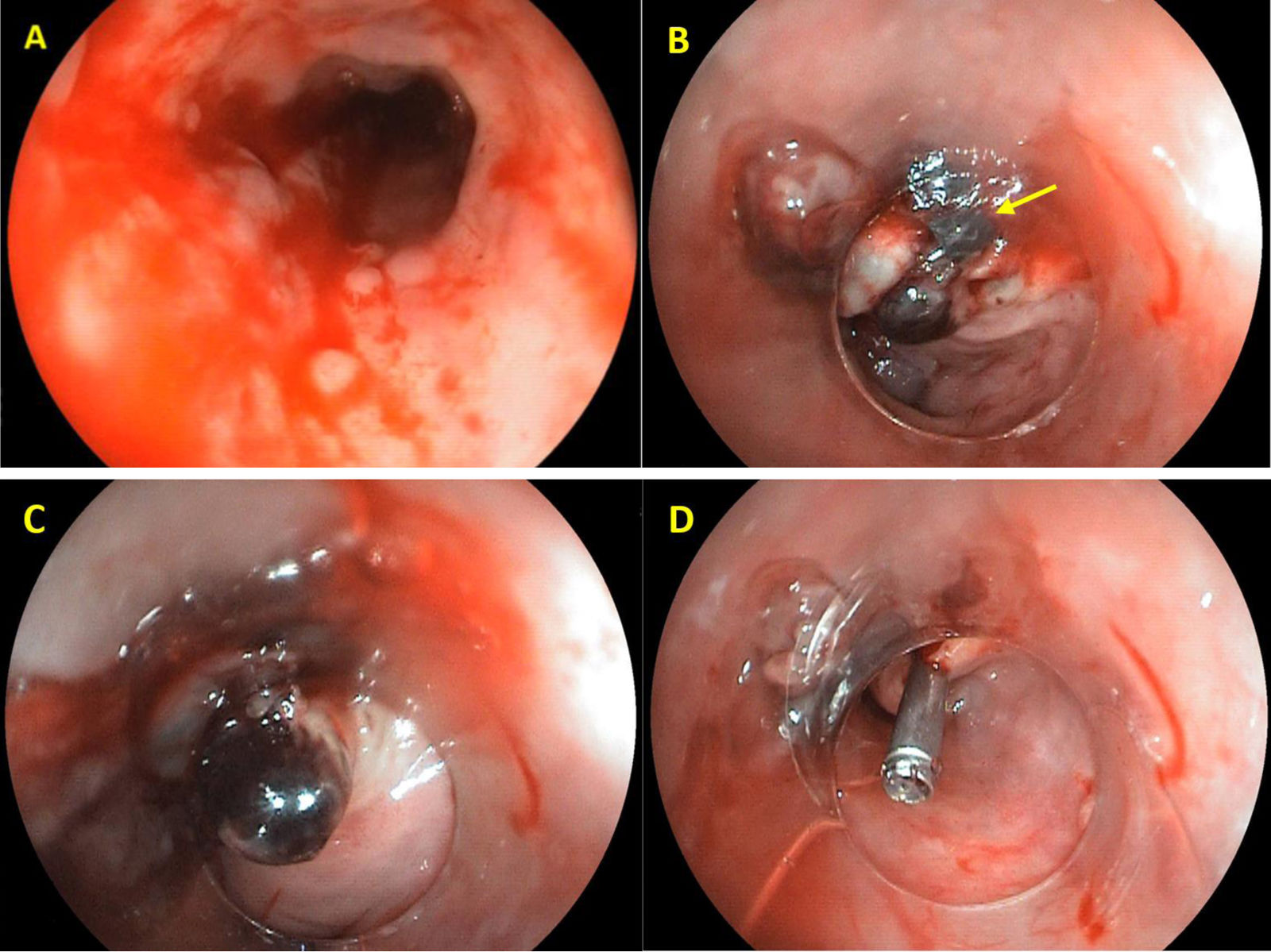

GDE was performed, revealing an abundant amount of blood in the esophagus (Fig. 2A) arising from an actively bleeding post-ligation ulcer. The previously placed elastic band was becoming detached (Fig. 2B) and came completely detached during the procedure (Fig. 2C). In addition, 3 large varicose cords that were distally ligated were identified. A new ligation at the level of the post-ligation ulcer was unsuccessfully attempted. With the aid of an endoscopic cup, a hemostatic clip was placed, achieving complete hemostasis (Fig. 2D).

The patient’s clinical evolution was good, and she was released after 5 days, with no complications.

The incidence of post-ligation bleeding (PLB) is from 2. 3 to 7 .3%,3 with a mortality rate of 22.3-24.5%.2,5

After EVL, the band remains attached to the esophageal wall for 3 to 7 days and thrombi develop in the strangulated vessels.5,6 The band then detaches, resulting in an ulcer that generally heals in 2 to 3 weeks.3 Premature detachment of the band exposes the vessel inside the ulcer, leading to PLB.7 The time from EVL to PLB is an average of 11 days.2

There is no consensus on bleed predictors after EVL.2 Some studies 3,5,6 have found that factors associated with PLB were hepatocellular carcinoma, higher Child-Pugh score, MELD score above 10, high prothrombin time, and suboptimum dose of propranolol. In the study by Reji et al., other associated factors were peptic esophagitis and a low hemoglobin level.2 Our patient had a Child B score of 7, a MELD score of 10, and mild anemia.

Other factors related to the endoscopic procedure are emergency EVL, the use of a higher number of bands, high-risk varices, larger varices, a higher number of esophageal varices,8,9 and associated gastric varices.3 Of those factors, emergency EVL is the strongest predictor for PLB.

Cases of variceal UGIB are usually managed with intravenous vasoactive agents and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). PPIs have been described in the literature as possibly reducing the magnitude of PLB, but different reports on PPI use found no effect on bleeding complications or mortality.2–4,10 One study reported a trend toward a higher mortality rate in patients that received only PPIs.6

Despite the high mortality rate, there is no standard treatment for PLB.6 Current treatment continues to be empiric and is based on the experience from individual centers. In a systematic review,5 the following were considered management options: new EVL, argon plasma coagulation, sclerotherapy, cyanoacrylate injection, epinephrine injection, HemoClip®, and Hemospray®. None of those techniques has been shown to be superior to another, and their use should be individualized, according to each case and center.

In the case of our patient, a new EVL was attempted, but despite intense aspiration, the band did not attach at that level, most likely due to the surrounding fibrosis from the previous ligations. Given the persistent active bleeding, hemostatic clip placement was decided upon, achieving complete hemostasis.

Author contributionsThe authors have participated in the concept and design of the article and in the writing and approval of the final version to be published.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that no experiments on humans were conducted for this work. We employed the patient data collection formats of our work center, maintaining patient anonymity. Informed consent was previously obtained. The authors declare that this article contains no personal information that could identify the patient. This work meets the current bioethical research norms and was authorized by our institutional ethics committee.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.