Cow's milk protein allergy is the most common cause of food allergy. The challenge test, either open or doubled-blind with a placebo control, is regarded as the criterion standard. Endoscopy and histologic findings are considered a method that can aid in the diagnosis of this entity.

AimsThe aim of this study was to describe the histopathologic findings in children suspected of cow's milk protein allergy that were seen at our hospital.

Material and methodsA descriptive, observational study was conducted on 116 children clinically suspected of presenting with cow's milk protein allergy that were seen at the Department of Gastroenterology and Nutrition of the Instituto Nacional de Pediatría. Upper endoscopy and rectosigmoidoscopy with biopsies were performed and the findings were described.

ResultsOf the 116 patients, 64 (55.17%) were girls and 52 (44.83%) were boys. The rectum was the site with the greatest presence of eosinophils per field in both groups, followed by the duodenum. In general, more than 15 eosinophils were found in 46% of the patients.

ConclusionsBetween 40 and 45% of the cases had the histologic criterion of more than 15 to 20 eosinophils per field and the rectosigmoid colon was the most affected site. Therefore, panendoscopy and rectosigmoidoscopy with biopsy and eosinophil count are suggested.

La alergia a las proteínas de la leche de vaca es la causa más común de alergia a alimentos. La prueba de reto ya sea abierta o doble ciego controlado con placebo, es considerada el estándar de oro. La endoscopia y los hallazgos histológicos son considerados métodos que pueden ayudar en el diagnóstico de esta entidad.

ObjetivosEl objetivo del presente trabajo fue describir los hallazgos histopatológicos en niños con sospecha de alergia a las proteínas de la leche de vaca atendidos en nuestro hospital.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional, descriptivo en 116 niños con sospecha clínica de alergia a las proteínas de la leche de vaca, atendidos en el Departamento de Gastroenterología y Nutrición del Instituto Nacional de Pediatría. Se efectúo endoscopia alta y rectosigmoidoscopia con toma de biopsias y se describieron los hallazgos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 116 pacientes, 64 (55.17%) del género femenino y 52 (44.83%) masculino. El sitio con mayor presencia de eosinófilos fue el recto en ambos grupos, seguido del duodeno; en general se encontró más de 15 eosinófilos por campo en el 46% de los pacientes.

ConclusionesEntre el 40-45% de los casos tuvieron el criterio histológico de más de 15-20 eosinófilos por campo siendo el sitio más afectado el rectosigmoides. Por lo tanto, se sugiere realizar panendoscopia y rectosigmoidoscopia con toma de biopsias y recuento de eosinófilos.

Food allergy is a diagnostic challenge, given that there is no laboratory test or radiology or imaging study that can sustain the diagnosis with good sensitivity and specificity. Currently, the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge test has the greatest sensitivity and specificity,1 but it is not a practical test for the clinician in his or her office and it is uncomfortable for the patients and their families. Therefore, it is necessary to search for different processes that support clinical suspicion.

Cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA) is the most common cause of food allergy in infants2,3 and is defined as an immunologic reaction to the proteins in cow's milk accompanied with clinical signs and symptoms.4 Its prevalence worldwide varies from 2.2 to 2.8%.5,6

CMPA is a very frequent, but unfortunately misdiagnosed, pathology in our environment, given that it is a clinical diagnosis in the majority of the cases.7

In the 1950s, CMPA was rarely diagnosed. Its suspicion and resulting diagnosis began to increase in 1970.1 The allergen suppression test is presently regarded as the criterion standard, but there are a large number of other tests and studies that include: skin tests, cow's milk-specific IgE and IgG antibody tests, the patch test, cell function tests, and endoscopy and colonoscopy with biopsy, all of which vary in sensitivity and specificity.8–14 We now know that CMPA can be caused by one or several proteins present in cow's milk and the immunologic mechanism may or may not be mediated by IgE.8,15 During the last few years, intestinal biopsy has gained much importance in CMPA diagnosis, because even though it is invasive, it allows us to obtain macroscopic and microscopic data of this entity. It can be useful when there is diagnostic doubt; the presence of more than 60 eosinophils in 6 high power fields (HPFs) and/or more than 15-20 eosinophils per field are very suggestive of this pathology.16–20 These histopathologic alterations can present all along the digestive tract (esophagus, stomach, duodenum, rectosigmoid colon) and cause symptoms depending on the affected site.

Thus, the aim of this study was to describe the histologic findings in patients suspected of having CMPA.

MethodsA descriptive, observational, prospective, and cross-sectional study was conducted on 116 children clinically suspected of presenting with cow's milk protein allergy. They were clinically evaluated by 3 pediatric gastroenterologists from the Department of Gastroenterology and Nutrition at the Instituto Nacional de Pediatría within the time frame of March 2008 to September 2013. The diagnosis was made with the open food challenge test. The following variables were obtained: age, sex, weight, height, clinical manifestations (regurgitation, irritability, crying crisis, abdominal distension, rectorrhagia, diarrhea, dyschezia, laryngeal spasm, bronchial spasm, atopic dermatitis, rash). The patients were divided into 2 groups: group I: patients with no complementary feeding (0-6 months of age) and group II: patients with complementary feeding (7-13 months of age). Panendoscopy and rectosigmoidoscopy with biopsy of the esophagus, antrum, duodenum, and rectum were carried out. Biopsy was considered positive with the presence of more than 15-20 eosinophils per HPF and/or more than 60 eosinophils in 6 fields.

The parents of the children of both groups gave their informed consent. Patients were excluded that presented with moderate or severe malnutrition, primary or secondary immunodeficiencies, metabolic or endocrine diseases, or neurologic damage.

The study was approved by the hospital's Research and Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics, proportions, and frequencies were used for the qualitative variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for the quantitative variables and the SPSS v 21.0 program was employed.

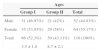

ResultsOf the 116 patients, 66 made up group I (56.8%) and 50 made up group II (43.10%). A total of 64 (55.17%) of the patients were female and 52 (44.83%) were male. The mean age of the group I patients was 3.5 months (1.8) and for group II it was 8.7 months (2.1). Table 1 shows the group distribution by age and sex.

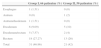

The most frequent clinical manifestations were regurgitation or vomiting, followed by irritability, abdominal distension, dyschezia, diarrhea, and rectorrhagia. Atopic dermatitis was the most frequent dermatologic manifestation, whereas the most common respiratory symptoms were laryngeal spasm, bronchial spasm, and apnea (table 2).

Clinical manifestations of cow's milk protein allergy.

| Group In (%) | Group IIn (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal manifestations | ||

| Regurgitation or vomiting | 64 (96.96) | 48 (96) |

| Irritability | 61 (92.42) | 35 (70) |

| Abdominal distension | 60 (90.90) | 35 (70) |

| Dyschezia | 55 (83.33) | 30 (60) |

| Diarrhea | 16 (24.24) | 20 (40) |

| Rectorrhagia | 15 (22.72) | 8 (16) |

| Dermatologic manifestations | ||

| Atopic dermatitis | 19 (28.78) | 20 (40) |

| Respiratory manifestations | ||

| Laryngeal spasm | 16 (24.24) | 18 (36) |

| Bronchial spasm | 10 (15.15) | 8 (16) |

| Apnea | 5 (7.57) | 0 (0) |

Table 3 shows the sites at which more than 15 eosinophils per field were more frequently found. The rectum was the most affected site, with 18 patients from group I (27.7%) and 13 from group II (26%).

DiscussionCMPA continues to be a diagnostic challenge for the general practitioner, pediatrician, and/or pediatric gastroenterologist, because the sensitivity and specificity of the different existing tests are low. Therefore, the best diagnostic method is clinical, with suppression of the offending protein and symptomatology improvement. Although conventional knowledge of allergic mechanisms involves IgE antibodies, thanks to histopathologic studies, it is now known that the presence of eosinophils in intestinal biopsies may be due to a hypersensitivity reaction that may or may not be mediated by IgE antibodies.21

Allergic proctocolitis is the most frequent cause of rectal bleeding in infants, but the other clinical presentations of CMPA are very frequent and they include gastrointestinal (50-90%),22–24 respiratory (20-30%),22–27 dermatologic (30-70%),22,24 neurologic,22–24 and systemic manifestations.24–26 Of the 116 patients studied, only 23 (19.8%) had rectorrhagia, but more than 95% presented with gastrointestinal symptomatology of CMPA (see table 2). This is concordant with reports by various authors stating that gastrointestinal manifestations are present in a high percentage of cases.22–24

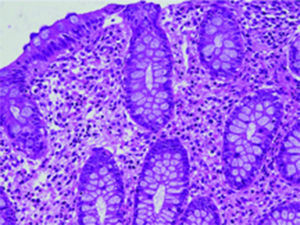

There are several studies related to both the endoscopic and histologic findings in children with CMPA. The most frequent endoscopic ones reported are focal erythema, erosions, and lymphoid nodular hyperplasia (fig. 1) and these alterations present in 40-90% of the cases.28,29 In regard to the histologic findings of the esophageal, gastric, duodenal, and rectal biopsies, the majority of authors agree that the presence of more than 60 eosinophils in 6 HPF and/or more than 15-20 per field are very suggestive of CMPA (fig. 2). Nevertheless, other reports in the literature state that 6-10 eosinophils/HPF can be suggestive of this pathology.29

In the 2 groups of patients studied, these findings (more than 60 eosinophils per 6 HPFs and/or more than 15 eosinophils per field) were encountered in the biopsies of 52 (44.8%) of the patients. In the biopsies, the rectosigmoid colon was the most affected site (31 patients), followed by the duodenum (12 patients), the antrum (2 patients), and the esophagus (one patient) (table 3). Endoscopic alterations only presented in 33% of the cases and they were focal erythema and erosions; lymphoid nodular hyperplasia presented in only 3 cases. This contrasts with results published by other authors at the international level; Goldman and Antonioli27 conducted a study on 20 patients with proctocolitis caused by CMPA and reported macroscopic findings during rectosigmoidoscopy of areas of focal erythema and nodular hyperplasia in 95% of the cases and the characteristic histologic findings of more than 15 eosinophils per HPF in 60% of the cases. Hwang et al. studied 38 patients with allergic proctocolitis and found endoscopic abnormalities in all the patients, lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in 94.7%, focal erythema in 5.3%, and the histologic finding of more than 60 eosinophils in the lamina propria in 10 HPFs in all the cases.30 This can all be explained based on the fact that the age of our patients was below 13 months, and as is to be expected, damage to the intestinal mucosa increases with age, as do focal erythema and nodular hyperplasia.

In our study, of the 18 patients with rectorrhagia, areas of focal erythema were found in 6 patients and lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in 2 during the rectosigmoidoscopy; there were histologic findings of more than 15-20 eosinophils per HPF in 10 (55.5%) patients. The absence of rectorrhagia does not exclude CMPA diagnosis. Given the above information, every child suspected of presenting with CMPA, in addition to always having upper endoscopy, should also undergo rectosigmoidoscopy and/or colonoscopy with biopsy, even if the macroscopic appearance is normal.28–31

In all the cases, the initial management in children being breast-fed was the total exclusion of milk and its by-products from the mother's diet. In cases of failure or when breast-feeding was not possible, treatment was based on extensively hydrolyzed formulas made from serum protein and/or casein, and if that failed, the change to elemental diets was made.

The main limitation of our study was the fact that the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge test, regarded as the criterion standard by the foremost international guidelines,32,33 was not utilized for CMPA diagnosis. Another limitation was the study's descriptive design and the lack of a control group.

ConclusionsCMPA continues to be a diagnostic challenge, but today the criterion standard is the double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge test. Treatment for the breast-fed infant is the complete suppression of milk and its derivatives from the mother's diet. In cases of failure or when breastfeeding is not possible, extensively hydrolyzed serum protein and/or casein formulas or elemental diets should be given. In all patients with CMPA suspicion that undergo upper endoscopy and rectosigmoidoscopy with biopsy, the pathologist must be requested to carry out an eosinophil count per field.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and were in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center in relation to the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study/article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cervantes-Bustamante R, Pedrero-Olivares I, Toro-Monjaraz EM, Murillo-Márquez P, Ramírez-Mayans JA, Montijo-Barrios E, et al. Hallazgos histopatológicos en niños con diagnóstico de alergia a las proteínas de la leche de la vaca. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2015;80:130–134.