Cases of recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP) in children have increased in recent years. RAP is characterized by two or more documented events of acute pancreatitis (AP) and occurs in 10-30% of cases of AP. CP is the end stage of progressive inflammation that manifests as fibrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma that eventually leads to exocrine and/or endocrine dysfunction.1,2

In children, there is usually more than one identified factor that contributes to its development and they are related to a broad range of etiologies (genetic, anatomic, obstructive, pharmacotoxic, traumatic, metabolic [inborn errors of metabolism], systemic, infectious, autoimmune, and idiopathic).3 Said conditions are related to morbidities, emergency room admissions, and hospitalizations.4

We describe herein 6 patients with RAP and 5 with CP, in whom the identified risk factors in the development of RAP and CP, proposed by the INSPPIRE group,5,6 were studied. Massive sequencing was carried out using the Illumina® platform. The characteristics of the RAP and CP cases are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The risk factors for developing both RAP and CP are similar and genetic causes have been identified in > 50% of the cases of RAP and in ∼75% of the cases of CP, with 17% of cases having more than one pathogenic variant, according to the INSPPIRE report.3,5

Clinical characteristics, identified factors, and radiologic findings in the recurrent acute pancreatitis group.

| Patient | BMI | Identified factor | Age (years) at onset of symptoms | Age (years) at diagnosis | Family history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, M | 97 | Genetic (PRSS1 pathogenic variant) | 3 | 3 | Pancreatitis (brother) |

| 2, F | 35 | Obstructive (cholelithiasis) | 6 | 6 | – |

| 3, F | 52 | Metabolic (hypertriglyceridemia) | 8 | 8 | – |

| 4, M | 26 | Idiopathic | 9 | 12 | – |

| 5, F | 92 | Obstructive (microlithiasis) | 4 | 5 | – |

| 6, M | 40 | Metabolic (hypercalcemia/primary hyperparathyroidism) | 13 | 13 | Pancreatitis (maternal aunt and grandmother) |

BMI: body mass index expressed in percentiles by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; F: female; M: male; PRSS1: cationic trypsinogen.

Clinical characteristics, identified factors, and radiologic findings in the chronic pancreatitis group.

| Patient | BMI | Identified factor | Age (years), at symptom onset | Age (years) at diagnosis | Family history | Imaging findings | EPIx | EPIn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, M | 8 | Genetic (PRSS1 pathogenic variant) | 12 | 12 | RAP (brother) | Calcification | – | + |

| 2, M | 4 | Genetic (CFTR+PRSS1 pathogenic variants) | 6 | 7 | Type I diabetes mellitus (father and maternal grandmother) | Main pancreatic duct dilation | + | – |

| 3, F | 10 | Genetic (PRSS1 pathogenic variant) | 10 | 11 | – | Calcification and fibrosis in biopsy | + | – |

| 4, F | 7 | Genetic (PRSS1 pathogenic variant) | 5 | 5 | – | Calcification | + | – |

| 5, M | 94 | Idiopathic | 12 | 13 | – | Calcification | + | – |

BMI: body mass index expressed in percentiles of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CFTR: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; EPIn: endocrine pancreatic insufficiency; EPIx: exocrine pancreatic insufficiency; F: female; M: male; PRSS1: cationic trypsinogen; RAP: recurrent acute pancreatitis.

The median age at the time of diagnosis was 8 years (interquartile range [IQR] 5-12), the median number of emergency room visits prior to diagnosis was 3 (IQR 2-5), and the median number of hospitalizations in the past year was 2 (IQR 0-2).

In a recent study on 479 children, demographic variables, risk factors, and treatment in RAP and CP were evaluated, and genetic variants were identified as the dominant risk factor.7 In our report, we documented a genetic variant in 45.4% of cases, a higher percentage than that reported by Saito et al. (39.1%).8 In the study by Vue et al., in which 33% (n=30/91) of the patients were Hispanic, 36% of the 91 cases had at least one mutation.1

In a case series on 115 children that included 20 with RAP (17%), 16 of them underwent genetic testing. In 6 of those patients, one pathogenic variant was found in one of the 4 gene panels (PRSS1 [cationic trypsinogen], SPINK1 [serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1], CFTR [cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator], and CTRC [chymotrypsin C]); CFTR was the most frequently found genetic variant, followed by PRSS1 and SPINK1.9 The difference from our findings was likely due to our small sample size and the higher prevalence of the CFTR mutation that is found in the White population. In the Mexican population, in a total of 55 patients (65.5% with AP; 34.5% with RAP), Sánchez-Ramírez et al. identified a frequency of 1.8% for the pathogenic variant in the CFTR gene, corresponding to one patient in the RAP subgroup. However, none of the children were studied for variants in the PRSS1 or SPINK1 genes, and no cases of CP were included.10

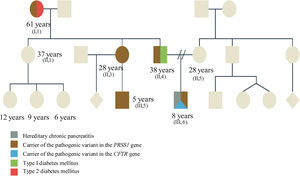

Four of our 5 patients with CP presented with heterozygous pathogenic variants in the PRSS1 gene (complete duplication of the coding region) and one patient presented with 2 heterozygous pathogenic variants (CFTR [p.Phe508del] and PRSS1 [complete duplication of the coding region]). In that sense, the presence of certain pathogenic variants in the PRSS1 gene (p.N29I or R122H) has been related to a greater probability of a progressive disease that evolves into CP, and later, even into pancreatic cancer.11Fig. 1 illustrates how a variant can be inherited in a family and expressed in distinct forms. Strikingly, all the patients analyzed presented with the same pathogenic variant in the PRSS1 gene, leading us to suspect they could have had a common ancestor.

The relatives with manifestations of type I diabetes mellitus and pancreatitis are described, as well as asymptomatic relatives. The patient presents with torpid progression by being a carrier, not only of the duplication in the PRSS1 gene, but also of a heterozygous variant in the CFTR gene, thus a torpid expression and progression is expected.

A positive family history for pancreatitis has been described to be more frequent in patients with pathogenic variants and 30% of patients with RAP or CP have a family history of pancreatitis, similar to our finding of 27.2%.1,7

We found 2 patients (RAP subgroup) with an obstructive factor. In a study on adult patients with RAP, Saraswat et al. reported that 75% of the microscopic studies of the gallbladder revealed cholesterol crystals and calcium bilirubinate granules associated with microlithiasis. Thirty months after microlithiasis treatment (ursodeoxycholic acid, sphincterotomy, or cholecystectomy), the patients were asymptomatic.12

In pediatrics, the metabolic risk factors for RAP and CP are related to diabetic ketoacidosis, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercalcemia associated with hyperparathyroidism, and less frequently, to inborn errors of metabolism.13 We found that 2 patients with RAP presented with a metabolic factor: one patient had hypertriglyceridemia (levels > 1,000mg/dl). Serum levels > 1,000mg/dl are an absolute risk factor for the development of AP. One of our patients presented with parathyroid adenoma, which is the most common cause of hypercalcemia (> 10.7mg/dl).14

Patients with a metabolic factor had a later mean age at presentation than the patients with RAP and no metabolic factor (10.5 vs. 7.16 years), a finding similar to that reported by Husain et al.14

Pediatric patients with symptoms of pancreatitis do not always undergo an extensive diagnostic evaluation. Therefore, we must promote a proactive position from the time of RAP diagnosis, emphasizing and prioritizing genetic testing.

We recommend that pediatric patients with no identifiable etiology of pancreatitis undergo genetic counseling, given that early typing of the risk factors could improve the therapeutic focus.9,13

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare they reviewed the clinical records to collect the data and that they were handled confidentially so that no patient could be individually identified. Neither authorization by the Ethics Committee nor signed statements of informed consent were required.

Financial disclosureNo specific grants were received from public sector agencies, the business sector, or non-profit organizations in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Macias-Flores JA, Rivera-Suazo Y, Mejía-Marin LJ. Factores identificados para desarrollar pancreatitis aguda recurrente y pancreatitis crónica: debemos considerar la etiología genética. Reporte de casos en niños mexicanos. Rev Gastroenterol Méx. 2023;88:296–299.