Patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) have a higher incidence of periodontal disease. Both conditions are related to the oral and gut microbiota dysbiosis that conditions systemic inflammation. In our population, the frequency and importance of that association have not been documented.

AimTo determine the prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with MASLD treated at a referral center in Veracruz.

Material and methodsA prospective, comparative, analytic, cross-sectional study was conducted on patients with MASLD and a group of healthy controls. Anthropometric characteristics, liver steatosis grade, dental involvement, and quality of life were analyzed. The statistical analysis included measures of central tendency and dispersion, as well as frequency and percentage. The two groups were compared using the Student’s t test or Wilcoxon test, the chi-square test, and the Pearson or Spearman correlations, employing the SPSS-5 program.

ResultsThirty-seven patients with MASLD were studied. Mean patient age was 56.3 ± 12.3 years, 70.3% were women, and mean BMI was 34.2 ± 5.9. A total of 18.9% of patients presented with gingivitis and 81.1% with periodontitis (p < 0.0001), compared with the controls (mean age 54.6 ± 9.8 years, 65.5% women, BMI 28.7 ± 5.7), in which 13.8% had gingivitis and 37.9% periodontitis. Steatosis grade and periodontal disease were significantly correlated (r = 0.412, p = 0.003), with no differences in food quality (r = –0.037, p = 0.798); 36.9% of patients reported a decrease in quality of life.

ConclusionsOur results showed an elevated prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with MASLD that negatively impacted quality of life, suggesting the need for comprehensive management.

Los pacientes con esteatosis hepática metabólica (MASLD) presentan mayor incidencia de enfermedades periodontales. Ambas condiciones están relacionadas con disbiosis de la microbiota oral e intestinal que condiciona inflamación sistémica. En nuestra población, no se ha documentado la frecuencia e importancia de esta asociación.

ObjetivoDeterminar la prevalencia de la enfermedad periodontal en pacientes con MASLD atendidos en un Centro de Referencia en Veracruz.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo transversal, comparativo y analítico en pacientes con MASLD, comparado con un grupo de sujetos sanos. Se analizaron las características antropométricas, grado de esteatosis hepática, afectación odontológica y calidad de vida. El análisis estadístico incluyó medidas de tendencia central, dispersión, frecuencias y porcentajes; se compararon ambos grupos mediante la prueba T de Student o Wilcoxon y chi-cuadrado y correlaciones con Pearson o Spearman, utilizando el programa SPSS-5.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 37 pacientes con MASLD, edad promedio de 56.3 ± 12.3 años, 70.3% mujeres, IMC 34.2 ± 5.9. Presentaron gingivitis el 18.9% y periodontitis el 81.1% (p < 0.0001) comparado con un grupo control (promedio de edad 54.6 ± 9.8 años, 65.5% mujeres, IMC 28.7 ± 5.7), donde la gingivitis fue del 13.8% y la periodontitis del 37.9%. Se encontró correlación significativa entre el grado de esteatosis y enfermedad periodontal (r = 0.412, p = 0.003), sin diferencias en la calidad de la alimentación (r = -0.037, p = 0.798), aunque el 36.9% de los casos reportaron afectación de la calidad de vida.

ConclusionesLos resultados evidencian elevada prevalencia de enfermedad periodontal en pacientes con MASLD, impactando negativamente su calidad de vida, lo que sugiere la necesidad de un manejo integral.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a highly prevalent entity worldwide, estimated to occur in 20-25% of the adult population, especially in women between the fourth and sixth decades of life. It has increased 4 to 5 times in patients with obesity and diabetes, and in Mexico, recent reports estimate a frequency of 17-46%.1–7 Its etiopathogenesis is complex and includes a genetic predisposition associated with different environmental and cultural factors, type of dietary habits, and a sedentary lifestyle, among others. This causes lipid accumulation in the hepatocyte, whose presence can vary from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and the development of carcinoma.8–10 Liver steatosis is due to the excessive synthesis of “de novo” triglycerides, whose increase favors the excessive synthesis of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), resulting in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs). TRLs circulate, affecting different organs, including the arterial endothelium, triggering atherosclerosis, with the risk of developing cardiovascular, brain, or kidney disease. Likewise, those patients have been shown to have a different gut microbiome pattern, whose dysbiosis causes proinflammatory cytokine production, and as a result, a low-intensity chronic inflammation process that favors the development of liver fibrosis.11–13

Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the periodontal tissues, which has been found to be associated with different metabolic and systemic inflammatory disorders. For a decade, different researchers in Asia have demonstrated the association of gingivitis and periodontitis with cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, diabetes, and MASLD. Those researchers have demonstrated oral microbiota dysbiosis with Porphyromonas gingivalis overgrowth, suggesting that periodontal disease has adverse effects on the pathophysiology of liver disease, based on the concept that periodontopathic bacteria are associated with a high frequency of MASLD. Likewise, the severity of MASLD has been reported to condition a lower response to treatment of dental diseases, and that its timely management improves the biochemical parameters of liver function and patient quality of life.14–20

Because there is a high prevalence of obesity and diabetes in Mexico and their association with periodontal disease is not widely known, we consider the present study to be of interest. Our aim was to study the frequency of said association and know its effect on the quality of life of the affected patients.

Material and methodsA descriptive, prospective, analytic, cross-sectional study was conducted that compared the prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with MAFLD (group A) with a population of controls without MASLD (group B), consecutively treated at the Gastroenterology Service of the Instituto de Investigaciones Médico-Biológicas and the Odontology Clinic of the School of Odontology of the Universidad Veracruzana in Veracruz, Mexico.

Sample determinationConvenience sampling was carried out within the January 2023-December 2024 time frame.

Inclusion, exclusion, and elimination criteriaMexican subjects of both sexes, above 18 years of age, who voluntarily agreed to participate after signing written statements of informed consent, were included in the study. Subjects with chronic and uncontrolled metabolic disease, those who were full denture wearers, in orthodontic treatment, or with cognitive and/or motor disability that would hinder them from understanding the study protocol were excluded from the study. Subjects with an incomplete evaluation program or a duplicate register were eliminated from the study.

InterventionsAnthropometric characteristicsAge, biologic sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and associated comorbidities were registered.

MASLD determinationMASLD was determined, based on evidence of liver steatosis through imaging methods plus the presence of a cardiometabolic risk factor (dyslipidemia, waist circumference > 102/88 cm, high blood pressure (HBP) > 130/85 mmHg, glucose level > 100-125 mg/dl, HbA1c of 5.7 to 6.4% or homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance > 2.5, C-reactive protein > 2 mg/dl). Transient elastography (FibroScan®) was carried out on all cases with MASLD, determining the levels of steatosis through the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP), based on the cutoff points proposed by Karlas et al.,21 classifying them from S0 to S3. Fibrosis grade was determined in kilopascals (kPa) and classified from F0 to F4, according to the METAVIR score.

Dental evaluationA periodontal questionnaire was applied to know the patient’s perception of his/her dental health and a detailed periodontal chart was carried out to determine whether there was periodontal disease (gingivitis and/or periodontitis) and classify it as mild, moderate, severe, or advanced. Halitosis grade was determined through a halimeter (Breath Checker®), classifying its intensity from absent to severe, as grades 1 to 4.

Evaluation of quality of food intakeA mini-survey to evaluate the quality of food intake called the Mini-ECCA (its Spanish acronym) was utilized. It consists of 12 items that evaluate the quality and quantity of foods and drinks the subject consumes. Based on the final score, quality is classified as very good (10-12), good (7-9), low (4-6), and very low (1-3).7

Quality of life evaluationThe chronic liver disease questionnaire-nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (CLDQ-NAFLD) instrument was applied. It contains 36 questions that analyze abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional health, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry, and classifies them as bad (36-107 points), regular (108-179 points), and good (180-252 points).

Statistical analysisThe numerical variables were reported as measures of central tendency and dispersion, and the categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage. Data distribution was evaluated with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and homoscedasticity with the Levene’s test. Group comparisons were made with the Student’s t test or the Wilcoxon test for the numerical variables, and the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for the categorical variables, as corresponded. Correlations were evaluated with the Spearman’s test and a logistic regression analysis was carried out, according to a p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27 software.

ResultsEighty-two subjects were studied; 16 were eliminated for not meeting the inclusion criteria and 4 due to an incomplete register. The final cohort of 66 cases was made up of 37 subjects diagnosed with MASLD (group A) and 29 healthy controls (group B).

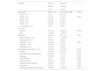

Anthropometric characteristics and associated comorbiditiesThe median age was 56.3 ± 12.3 years (range 19-88) in group A and 54.6 ± 9.8 years (range 21-88) in group B (p = 0.578). The most frequent age range in the two groups was the sixth and seventh decades of life, with 23 cases (62.1%) in group A and 13 cases (44.9%) in group B (p = 0.054). Female biologic sex was predominant in the two groups. The mean BMI in the patients with MASLD was 34.2 ± 5.9 kg/m², compared with 28.7 ± 5.7 kg/m² in the control group (p < 0.005). Grade I and grade II obesity predominated in group A, with 25 cases (67.6%), and there were 18 cases (82.0%) with normal weight or overweight in group B (p < 0.0022). Table 1 shows the rest of the comorbidities.

Anthropometric characteristics and associated comorbidities in group A (patients with MASLD) and group B (healthy controls).

| Variable | Group A | Group B | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| MASLD | Controls | ||

| n = 37 | n = 29 | ||

| Age (years) | 56.3 ± 12.3 | 54.6 ± 9.8(21-88) | 0.578 |

| 20-29, n (%) | 1 (2.7) | 8 (27.6) | |

| 30-39, n (%) | 5 (13.5) | 4 (13.7) | 0.054 |

| 40-49, n (%) | 6 (16.2) | 2 (6.9) | |

| 50-59, n (%) | 14(37.8) | 7 (24.2) | |

| 60-69, n (%) | 9 (24.3) | 6 (20.7) | |

| 70 and older, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Sex n (%) | |||

| Women | 26 (70.3) | 19 (65.5) | 0.799 |

| Men | 11 (29.7) | 10(34.5) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.2 ± 5.9 | 28.7 ± 5.7 | 0.005 |

| Normal weight, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 11 (37.9) | |

| Overweight n, (%) | 5 (13.5) | 7 (24.1) | |

| Obesity I, n (%) | 15 (40.6) | 6 (20.8) | 0.022 |

| Obesity II, n (%) | 10 (27.0) | 3 (10.3) | |

| Obesity III, n (%) | 5 (13.5) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Associated comorbidities, n (%) | 32 (82.6) | 14 (48.3) | 0.018 |

| Obesity | 20 (90.1) | 6 (20.7) | 0.005 |

| Essential arterial hypertension | 14 (37.8) | 3 (10.3) | 0.214 |

| Diabetes | 12 (32.4) | 1 (3.4) | 0.052 |

| Heart disease | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0%) | 0.860 |

| Kidney disease | 4 (10.8) | 4 (13.8) | 0.185 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 21(56.8) | 1 (3.4) | 0.016 |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (13.5) | 1 (3.4) | 0.484 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 17(45.9) | 10 (34.5) | 0.199 |

BMI: body mass index; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

Liver steatosis was corroborated through liver elastography in 37 patients (100%) in group A, with grade S1 in 10 cases (27.3%), S2 in 5 cases (13.5%), and S3 in 22 cases (59.5%). There were no signs of liver fibrosis in 22 cases (59.5%) with MASLD, and of the remaining 15 cases (40.5%), 2 (5.4%) had F1, 8 (21.6%) had F2, 3 (8.1%) had F3, and 2 (5.4%) had F4 (Table 2).

Results of transient liver elastography with FibroScan in patients with MASLD.

| Steatosis and fibrosis grades by FibroScan | MASLD |

|---|---|

| n = 37 | |

| Liver steatosis n (%) | |

| S1 | 10 (27.3) |

| S2 | 5 (13.5) |

| S3 | 22 (59.5) |

| Liver fibrosis n (%) | |

| F0 | 22 (59.5) |

| F1 | 2 (5.4) |

| F2 | 8 (21.6) |

| F3 | 3 (8.1) |

| F4 | 2 (5.4) |

MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

The results for periodontal disease perception in group A were the following: bleeding gums in 19 subjects (51.4%), bad taste in the mouth in 18 (48.6%), perceived halitosis in 16 (43.2%), and sensitive teeth in 16 (43.2%). In group B, 13 subjects (44.83%) had perceived halitosis, 11 (37.9%) had sensitive teeth and bleeding gums, and 11 (37.9%) had a bad taste in the mouth. Table 3 shows there were no significant differences between the two groups.

Comparison of the results of the periodontal disease perception questionnaire in patients with MASLD and the control group.

| Variable | MASLD | Controls | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 | n = 29 | ||

| Periodontal disease perception questionnaire | |||

| Bleeding gums, n (%) | 19 (51.4) | 11(37.9) | 0.458 |

| Bad taste in the mouth, n (%) | 18 (48.6) | 11 (37.9) | 0.571 |

| Perceived halitosis, n (%) | 16 (43.2) | 13 (44.83) | 0.273 |

| Interdental space, n (%) | 23 (62.2) | 19 (65.5) | 0.760 |

| Long teeth, n (%) | 6 (16.2) | 14(20.7) | 0.744 |

| Sensitive teeth, n (%) | 16 (43.2) | 13 (37.9) | 0.830 |

| Tooth movement, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 6 (20.7) | 0.106 |

MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

The odontogram revealed the presence of periodontal disease (gingivitis and/or periodontitis) in the 37 (100%) group A patients and in 15 (61.7%) of the group B patients. Periodontitis was the most frequent alteration, with 30 patients (81.1%) in group A and 11 (37.9%) in group B. Periodontitis was more severe in the patients with MASLD and was advanced in 15 (50%). Only 2 subjects (6.9%) in the control group had advanced periodontitis (p = 0.0001) (Table 4).

Comparison of periodontal disease frequency in patients with MASLD and the control group.

| Variable | MASLD | Controls | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 | n = 29 | ||

| Periodontal disease | |||

| Gingivitis n (%) | 7 (18.9) | 4 (13.8) | |

| Periodontitis n (%) | 30 (81.1) | 11 (37.9) | |

| Absent | 0(0.0) | 10(34.5) | 0.0001 |

| Mild | 7 (23.3) | 1 (3.5) | |

| Moderate | 5 (16.7) | 3(10.3) | |

| Severe | 3 (10.0) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Advanced | 15 (50.0) | 2 (6.9) | |

MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

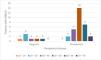

The age group with a higher prevalence of periodontal disease in the MASLD group was 50 to 59 years, with 15 cases (40.5%), followed by 60 to 69 years, with 8 cases (21.6%). The remaining 13 patients (35.1%) were in the other age groups (Fig. 1).

A sub-analysis was carried out on the MASLD patients that presented with type 2 diabetes mellitus and the MASLD patients without diabetes. The prevalence of periodontal disease was 100% in the group with type 2 diabetes mellitus, compared with 78.8% in the group without diabetes (p = 0.254). There were also differences in the presence of extreme halitosis (100% vs 78.1%, p = 0.718) and gingival problems (40% vs 21.2%, p = 0.357) between group A and group B, respectively. However, the results were not statistically significant.

In the 7 patients with gingivitis, the steatosis grade was S1 in one patient (14.3%), S2 in one patient (14.3%), and S3 in 5 patients (71.4%), whereas in the patients with periodontitis, it was S1 in 9 cases (30.0%), S2 in 4 cases (13.3%), and S3 in 17 cases (56.4%) (Table 5).

Fibrosis grade in the patients with gingivitis was F2 in only one case (14.3%), whereas in the patients with periodontitis, it was F0 in 16 cases (53.4%), F1 in 2 cases (6.7%), F2 in 7 cases (23.3%), F3 in 3 cases (10.0%), and F4 in 2 cases (6.7%) (Table 6).

Fibrosis severity distribution in the patients with periodontal disease.

| Periodontal disease | Grado de Fibrosis | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0 = ≤ 6.5 | F1 = 6.5-6.9 | F2 = 7-7.9 | F3 = 8-10 | F4 = 10.1-15 | ||

| Gingivitis | 6 (26.27 | 0 | 1 (14.3%) | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Periodontitis | 16 (53.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 7 (23.3%) | 3 (10.0%) | 2 (6.7%) | 30 |

| Total | 22 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 37 |

Halitosis was registered in all the group A patients, classified as severe in 5 cases (13.9%) and extreme in 31 cases (83.8%). In group B, halitosis was not detected in 6 cases (20.7%), and was mild in 9 cases (31%), moderate in 5 cases (17.3%), and severe or extreme in only 9 cases (31%) (p = 0.005) (Table 7).

Halitosis grade measurement and halitosis classification by halimetry in patients with MASLD and controls.

| Variable | MASLD | Controls | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 | n = 29 | ||

| Halimetry evaluation | |||

| Absence of halitosis | 0 (0) | 6(20.7) | |

| Mild | 0 (0) | 9 (31.0) | |

| Moderate | 1 (2.8) | 5 (17.3) | 0.005 |

| Severe | 5 (13.9) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Extreme | 31 (83.8) | 7(24.1) | |

MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

Utilizing the Mini-ECCA questionnaire, the patients with MASLD had a score of 7.5 ± 2.3 and the controls had a score of 6.4 ± 2.8 (p = 0.199). The quality of food intake was very good or good in 25 patients (67.6%) in group A and 12 (41.1%) in group B, it was low in 9 patients (24.3%) in group A and 13 (44.8%) in group B, and very low in 3 patients (8.1%) in group A and 4 (13.8%) in group B (p = 0.325). There were no statistically significant differences in the scores or quality of food intake classifications (Table 8).

Results of the mini-survey for evaluating quality of food intake (Mini-ECCA) in patients with MASLD and controls.

| Variable | MASLD | Controls | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 | n = 29 | ||

| Mini-ECCA | |||

| Mini-ECCA questionnaire score | 7.5 ± 2.3 | 6.4 ± 2.8 | 0.199 |

| Quality of food intake | |||

| Very good | 10 (27.0%) | 4 (13.8%) | |

| Good | 15 (40.6%) | 8 (27.6%) | 0.325 |

| Low | 9 (24.3%) | 13 (44.8%) | |

| Very low | 3 (8.1%) | 4 (13.8%) | |

ECCA: encuesta decalidad deconsumoalimentario (survey on the quality of food intake); MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

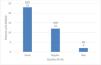

Quality of life in the patients with MASLD was considered good in 23 cases (62.2%), regular in 12 cases (32.4%), and bad in 2 cases (5.4%) (Fig. 2).

In the CLDQ-NAFLD, the total score was 198 (158.5-209) in group A and 209 (189-230) in group B (p = 0.036). There was a statistically significant difference in the sub-scales of activity (26 cases [19.5-30] vs 34 [31-35], p ≤ 0.0001), systemic symptoms (33 [26–36] vs 37 [31-40], p = 0.018), and worry (37 [29.5-43] vs 49 [41-56], (p = 0.0001). There were 51 cases (39-57) in group A vs 49 (45-56) in group B (p = 0.785) on the emotional health subscale and 29.4 ± 7.8 vs 31 ± 6.0 (p = 0.426) on the fatigue subscale. In addition, abdominal symptoms were found in the two groups, with 15 cases (12-20) in the patients with MASLD and 18 (14-21) in the healthy subjects (p = 0.289) (Table 9).

Total quality of life score in general and on the subscales of activity, emotional health, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.

| Variable | MASLD | Controls | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 | n = 29 | ||

| CLDQ-NAFLD instrument | |||

| Total quality of life score | 198 (158.5-309.0) | 209 (189-239) | 0.036 |

| Abdominal symptoms | 15 (12-20) | 18 (14-21) | 0.289 |

| Activity | 26 (19.5-30) | 34 (31-35) | 0.0001 |

| Emotional health | 51 (39-57) | 49 (45-56) | 0.785 |

| Fatigue | 29.4 ± 7.8 | 31 ± 6 | 0.426 |

| Systemic symptoms | 33 (26-36) | 37 (31-40) | 0.018 |

| Worry | 37 (29.5-43) | 49 (41-56) | 0.0001 |

CLDQ-NAFLD: chronic liver disease questionnaire-nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

MASLD has become one of the main causes of chronic liver disease, with an estimated worldwide incidence of 20-25% in adults, a predominance in women, and variations in the five regions of the world. Its prevalence has increased in the past decades due to significant changes in lifestyle that have conditioned a notable rise in obesity and metabolic syndrome rates, in genetically predisposed patients. The reported prevalence in Latin America and in the Spanish-speaking population in the United States surpasses the prevalence in the other regions of the world.19,20 MASLD is considered a public health problem in Mexico, and holds first place in both child and adult populations, with a frequency of 17-46%.3,6,9

Since 2010, the relation between MASLD and periodontal disease has sparked the interest of many research groups, who have reported that the prevalence of MAFLD increases with the severity of periodontal disease, and patients with advanced periodontitis have a 3 to 4-times higher risk for liver events than normal subjects, and a decrease in quality of life. Thus, it is important to establish association and severity, as well as the repercussions on quality of life, to provide timely and effective multidisciplinary management.22–25

Our study revealed an elevated frequency of periodontal disease in patients with MASLD, with periodontitis in 81.1% of patients and gingivitis in 37.9%, whereas in the healthy controls those rates were 37.9% and 13.8%, respectively (p = 0.0001). Similar results for periodontitis (80.5%) have been reported by Asian groups.24 In our study, women were the predominant sex in both groups, at 70.3% and 65.5%, respectively, which are higher figures than those reported in North America, Europe, and Asia. This is most likely due to greater voluntary participation in our study by women and does not necessarily reflect actual predominance of either sex. The most affected age group was between the fifth and seventh decades of life.26,27

MASLD and periodontal disease form part of metabolic syndrome and share similar risk factors.28,29 In our MASLD group, 90.1% of the patients presented with obesity (p = 0.005), 32.4% with diabetes (p = 0.214), and 10.3% with HBP (p = 0.052), superior to the percentages in the controls. Interestingly, an important group of our patients stated having upper gastrointestinal disorders, such as dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (p = 0.018). Even more striking was the significant correlation between the presence of irritable bowel syndrome and both MASLD (OR 5.2, 95% CI 1.2-21.7, p = 0.016) and periodontal disease (OR 5.6, 95% CI 3.0-10.5, p ≤ 0.0001), compared with the general population.30

The dental evaluation through the application of the periodontal disease questionnaire showed an elevated prevalence of dental symptoms in patients with MASLD, such as bleeding gums 51.4% (p = 0.458), bad taste in the mouth 48.6% (p = 0.571), perceived halitosis 43.2% (p = 0.273), and sensitive teeth 43.2% (p = 0.830) vs normal subjects. Halitosis quantification enabled its presence to be established in 100% of the patients with MASLD, most cases of which were extreme (3.8%), whereas in the control group, it was present in 79.3% of the subjects, with only mild or moderate cases (p = 0.005). The odontogram revealed that 100% of the patients with MASLD had periodontal disease, especially periodontitis (81.1%), and it was severe or advanced in 60%, whereas it was present in 37.9% of the controls and less severe (p = 0.00001). The most affected age group was between 50 and 69 years, in 62.1%, which was a higher age than that reported by different authors.21,31,32

Liver elastography enabled the grades of steatosis and fibrosis in the patients with MASLD to be correlated with the severity of periodontal disease. Grade S2 and grade S3 steatosis was found in 53% of the cases, and there was an increase in periodontal disease severity, the higher the grade of liver involvement. There was liver fibrosis in close to 60% of the cases with more advanced disease. No other studies have been published in relation to the findings of our study.

The quality of food intake evaluated by the Mini-ECCA showed a score of 7.5 ± 2.3 in the patients with MASLD and of 6.4 ± 2.8 in the controls (p = 0.199). Low quality was found in 24.3% and very low quality in 8.1% of the group A patients and 44.8% and 13.8%, respectively, in group B. There was no statistically significant correlation between the two groups, and so we do not consider food quality as a factor in the association between MASLD and periodontal disease.33–35

The results of the quality-of-life evaluation in the MASLD group showed that it was affected in 37.6% of the cases, reported as regular in 32.4% and bad in 5.4%. There was a positive correlation in favor of MASLD regarding the BMI (0.394) (p = 0.004), activity (–0.435) (p = 0.001), systemic symptoms (–0.29 (p = 0.037), and worry –0.442 (p = 0.001), as shown in Table 10.

Correlations between the presence of MASLD, with anthropometric data and CLDQ-NAFLD instrument scales, and the detailed periodontal chart.

| Variable | Correlation | p |

|---|---|---|

| MASLD-BMI | 0.394 | p = 0.004 |

| MASLD-Activity (CLDQ-NAFLD) | −0.435 | p = 0.001 |

| MASLD-Systemic symptoms (CLDQ-NAFLD) | −0.291 | p = 0.037 |

| MASLD- Worry (CLDQ-NAFLD) | −0.442 | p = 0.001 |

| MASLD-Total score (CLDQ-NAFLD) | −0.288 | p = 0.038 |

| MASLD-Periodontal disease | 0.619 | p < 0.0001 |

| MASLD- Periodontal disease phase | 0.442 | p = 0.001 |

BMI: body mass index; CLDQ-NAFLD: chronic liver disease questionnaire-nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

The results confirm a strong association between MASLD and periodontal disease, with no statistical significance with the presence of diabetes mellitus. In addition, periodontal disease was more severe, as the severity of liver steatosis increased. Therefore, we consider multidisciplinary management of these entities essential for offering patients better quality of life.

ConclusionsOur study results showed an elevated prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with MASLD. Both conditions share a pathophysiogenesis related to metabolic syndrome, especially in genetically predisposed patients. Periodontitis was the most common periodontal disease observed in our patients. There was a predominance of female sex, with a 50 to 69-year age range. In addition, liver steatosis severity was associated with greater periodontal disease severity, but quality of food intake was not shown to be an influential factor in said association. Lastly, it is important to point out that 37.6% of patients reported a negative impact on quality of life, underlining the need for a comprehensive approach in the management of these conditions.

Ethical considerationsTo guarantee compliance with and adherence to ethics and research regulations, all participants in the study gave their statements of informed consent before the evaluations. The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Bioethics Committee of the School of Medicine of the Universidad Veracruzana with number ER-2022-059. The study was conducted by strictly respecting the official norms of data protection and the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participant data were treated with strict confidentiality and security measures, including the de-identification of and restricted access to authorized personnel. The participants had the right to leave the study at any time with no penalization.

Financial disclosureThe authors declare that no external financial support was received and that resources from the participating institutions were utilized.

José María Remes Troche is a speaker for Carnot and Alfasigma; Ana Delfina Cano Contreras is a speaker for Medix. The rest of the authors declare they have no conflict of interest in relation to conducting the present research study.