Bile acid malabsorption (BAM) is responsible for 30% of cases of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) or functional diarrhea and 63.5% of cases of diarrhea following cholecystectomy. 75SeHCAT is the gold standard diagnostic method but is unavailable in Mexico. Alternatively, primary bile acid (PBA) and total bile acid (TBA) determination in 48 h stools and 7αC4 measurement have been proposed as screening tests.

ObjectiveOur aim was to evaluate the experience with PBAs and/or TBAs and to determine whether 7αC4 is a good screening biomarker for BAM in clinical practice.

Material and methodsAn ambispective study of patients with chronic diarrhea was conducted. BAM was considered present with 7αC4 > 55 ng/mL (cost $420.00 USD), PBAs ≥ 9.8%, TBAs > 2,337 μmol/48 h, or TBAs > 1,000 μmol/48 h + PBAs > 4% (TBAs + PBAs) ($405.00 USD). However, those tests must be shipped to the US for their analysis (total cost $825.00 USD). Data were compared using the chi-square test and Student’s t test, and Spearman’s Rho correlations were calculated.

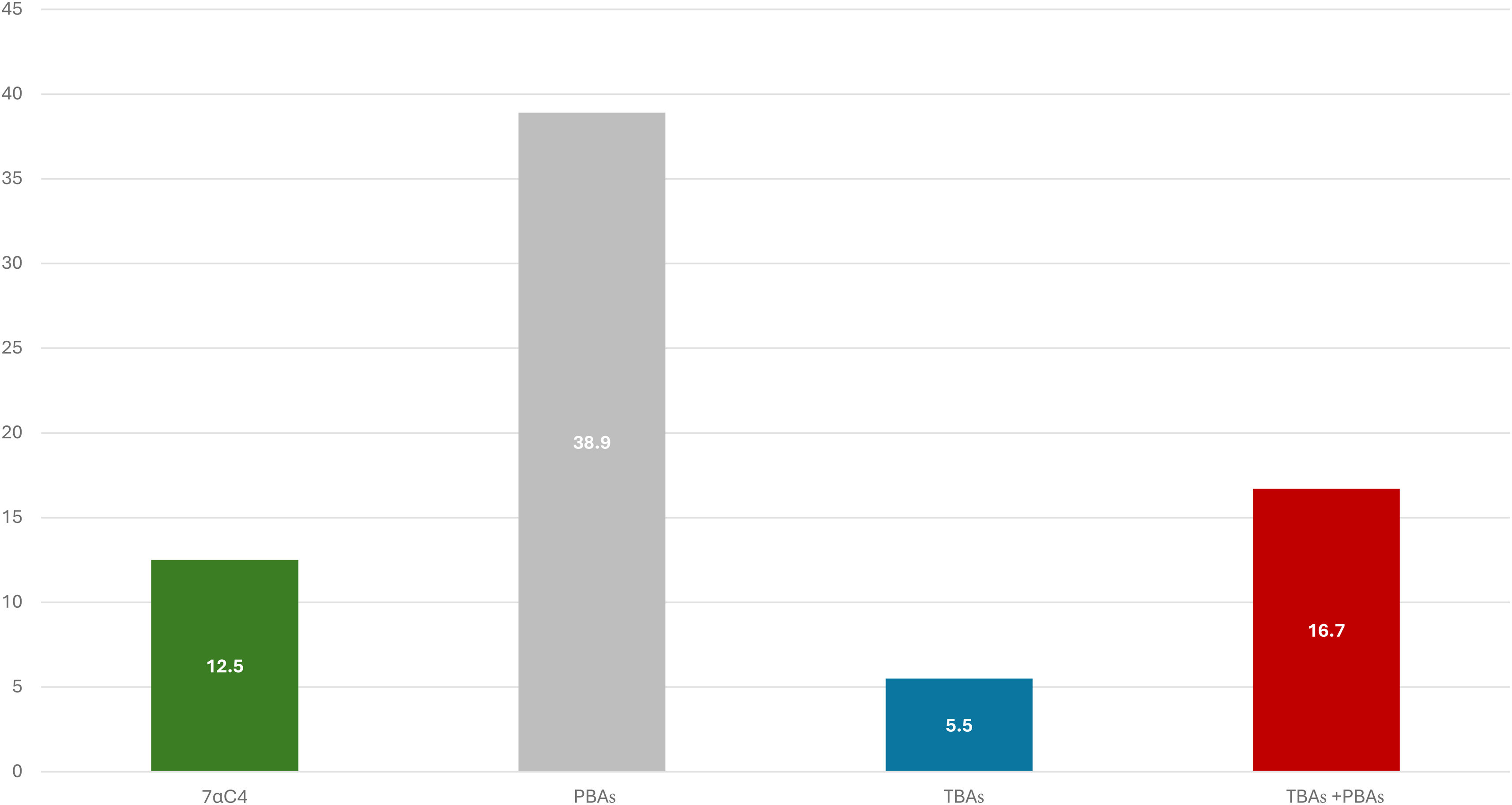

ResultsWe analyzed 48 patients with 7αC4 (age: 58.4 ± 16.9, women: 54.2%). BAM was confirmed by 7αC4 in 12.5%, by PBAs in 38.9%; by TBAs in 5.5%, and by TBAs + PBAs in 16.7%. We found elevated 7αC4 in patients with high or normal PBA/TBA levels (correlation with TBAs: 0.542, p = 0.020; PBAs: -0.127, p = 0.605; TBAs + PBAs: -0.200, p = 0.426). Lastly, BAM identified by 7αC4 was more frequent in patients with previous cholecystectomy (22.7%) vs. those without (3.8%).

ConclusionsOur study confirms that 7αC4 correlates well with TBAs and is a good biomarker for BAM screening because it can be elevated, despite normal PBA/TBA levels. Additionally, it represents a 49% cost savings in BAM investigation.

La malabsorción de ácidos biliares (MAAB) causa el 30% de los casos de síndrome de intestino irritable con diarrea (IBS-D) o diarrea funcional, y 63.5% de diarrea por colecistectomía. La prueba diagnóstica de referencia es 75SeHCAT, no disponible localmente. Alternativamente se ha propuesto la determinación de ácidos biliares primarios (ABP) y totales (ABT) en heces de 48 horas, y 7αC4 sérico como tamizaje.

ObjetivoEvaluar la experiencia con ABP y/o ABT, y determinar si 7αC4 es un buen biomarcador para MAAB en la clínica.

Materiales y métodosEstudio ambispectivo de pacientes con diarrea crónica. Se consideró MAAB con 7αC4 > 55 ng/mL (costo $420.00 US); ABP ≥ 9.8%; ABT>2337 μmol/48 hrs; o ABT>1000 μmol/48 hrs + ABP > 4% (ABT + ABP) ($405.00 US). Sin embargo, estas deben ser enviada a USA para su análisis (total $825.00 US). Los datos se compararon mediante X2, t-Student, y correlaciones mediante Rho de Spearman.

ResultadosSe analizaron 48 pacientes estudiados con 7αC4 (edad: 58.4 ± 16.9, mujeres: 54.2%). Se confirmó MAAB en 12.5% MAAB por 7αC4, 38.9% por ABP, 5.5% por ABT, y 16.7% con ABP + ABT. Se encontró 7αC4 elevado tanto en aquellos con ABP y/o ABT elevados o normales (correlación con ABT: 0.542, p = 0.020; ABP: -0.127, p = 0.605; ABT + ABP: -0.200; p = 0.426). Finalmente, la MAAB por 7αC4 fue más frecuente en pacientes con (22.7%) vs. sin (3.8%) colecistectomía previa.

ConclusionesEste estudio confirma que 7αC4 se correlaciona adecuadamente con ABT y es un buen biomarcador para tamizaje de MAAB, ya que puede estar elevado a pesar de ABP/ABT normales. Además, representa un ahorro del 49% en el costo del estudio de MAAB.

The 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (also known as 7α-hydroxycholesterol or 7αC4) is a steroidal intermediate in the synthesis of bile acids (BAs) from cholesterol occurring in the liver, by the rate-limiting enzyme, 7α-hydroxylase.1 7αC4 is then further metabolized to form the primary BAs (PBAs), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) and cholic acid (CA).2 These primary BAs are subsequently conjugated with taurine or glycine to increase their solubility and facilitate their secretion into the bile. They are then stored in the gallbladder to be delivered into the duodenum to emulsify fats and fat-soluble vitamins, as they are essential for their digestion and absorption.3 Around 95% of the BAs are reabsorbed mainly in the terminal ileum and then bind to the nuclear farnesoid X receptor (FXR), promoting the synthesis and release of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF-19). FGF-19 enters the enterohepatic circulation, leading to the inhibition of the rate-limiting enzyme, 7α-hydroxylase, thereby decreasing the hepatic synthesis of BA.4 The remaining 5% of the BAs that are not absorbed in the ileum reach the colon, where they are deconjugated by bacterial bile salt hydrolases and 7α-hydroxylating bacteria to produce secondary BAs, which stimulate fluid secretion and increase mucosal permeability and colonic motility, as a result of several mechanisms.5–7 Therefore, an excess of BAs in the colon can induce diarrhea, increased inflammation, and microbiome disruption.8–10

The estimated prevalence of bile acid malabsorption (BAM) in Western countries is around 1%.11 Specifically, approximately 30% of the cases of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) and/or functional diarrhea, and up to 63.5% of cases of diarrhea associated with previous cholecystectomy, are caused by BAM.12–16 This condition may arise from different pathophysiologic processes, thereby BAM can be classified into four types: type 1 is the result of ileal disease (e.g., Crohn’s disease); type 2 is idiopathic and can be present in patients with IBS-D or functional diarrhea, since most of them have no defect in bile acid absorption or clear gastrointestinal disease; type 3 is due to secondary malabsorption not associated with ileal dysfunction (e.g., chronic pancreatitis or cholecystectomy); type 4 is the result of increased BA synthesis without a clear sign of impaired BA reabsorption, most cases of which are induced by hypertriglyceridemia or metformin.17–19

The 75 selenium homotaurocholic acid test (75SeHCAT) is the gold standard for diagnosing BAM because it has the highest sensitivity and specificity.20–22 It is a nuclear medicine test with very limited availability in Latin America, and even in the rest of the world, except at very select academic centers.11,17,23 Determining the PBAs and/or total BAs (TBAs), combined with fasting serum 7αC4, has been proposed as an alternative method.12,15,24

Unfortunately, these tests are not readily available in Mexico. In addition, the samples must be shipped to the United States (US) for processing, the 48-h stool collection is uncomfortable for patients, and it is expensive (48 h stool BA: $405.00 USD and serum 7αC4: $420.00 USD, for a total of $825.00 USD). We have also observed discrepancies in the diagnoses of BAM, according to the 48-h stool BA and 7αC4. Due to these limitations, our aim was to evaluate the experience with the use of these biomarkers for BAM, and to determine whether 7αC4 by itself is a good screening marker in clinical practice in Mexico.

Material and methodsWe conducted an ambispective study of patients with chronic diarrhea or abdominal bloating/distension who consulted a specialized clinic for gastrointestinal motility and disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) in Mexico City and were suspected of having BAM. The patients’ medical records were reviewed and separated into those who were given 7αC4 in serum after 8 hours of fasting (Prometheus Laboratories, San Diego, CA) and/or BAs in 48-h stools (Mayo Clinic Laboratories, Rochester, MIN). The samples were retrieved at a local laboratory that shipped the samples to the US for analysis. Accordingly, BAM was considered when 7αC4 was > 55 ng/ml, PBAs ≥ 9.8%, TBAs > 2,337 μmol/48 hours, or TBAs > 1,000 μmol/48 hours + PBAs > 4% (TBAs + PBAs). TBAs + PBAs was derived from the individual measurements of TBAs and PBAs.

Statistical analysisThe data were obtained by retrospectively reviewing the records of outpatients that were previously studied at the clinic for BAM diarrhea using serum 7αC4. Data were expressed in percentages, means, medians, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and were compared using the chi-square test and Student’s t test when appropriate. Correlations between 7αC4 and PBAs or TBAs in 48-h stools were calculated using Spearman’s Rho. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerationsInformed consent was not needed because the study was based on a retrospective analysis of patients that were previously studied at the clinic, and no experimental intervention was performed, making Ethics Committee approval unnecessary. Finally, no personal data or images that could identify any patient or subject were used, and so patient consent was not required.

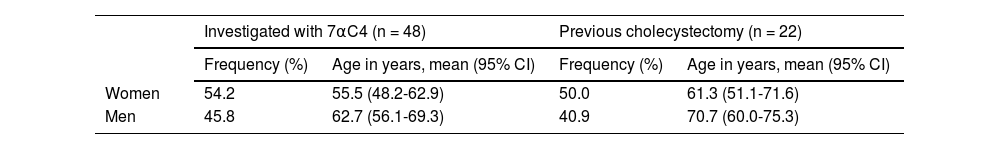

ResultsPatientsThe records of 48 consecutive patients that underwent 7αC4 testing were reviewed. There was a slight predominance of women, compared with men, but men were older than women (Table 1). Twenty-one of the patients (women: 7) were diagnosed with IBS-D, functional diarrhea, or other DGBIs with concomitant diarrhea, whereas 29 patients (women: 19) had other diagnoses, such as celiac disease or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). In addition, 22 (45.8%) patients had previously been cholecystectomized (Table 1).

Bile acid malabsorption (BAM)In addition to 7αC4, 19 patients had been simultaneously tested for PBAs and 18 for TBAs using 48-h stool collection. Eleven patients (22.9%) were positive for BAM, based on any of the three methodologies; they included 7 women (age: 54.7 ± 19.7 years) and 4 men (age: 74.0 ± 3.9 years). The frequency of BAM, based on the three specific methodologies that were investigated, are depicted in Fig. 1. BAM was confirmed by 7αC4 in 6 of the 48 patients (12.5%), but the highest prevalence was found with fecal PBAs, in 7 out of 18 patients (38.9%).

Correlations between 7αC4 and 48-h stool BAsOf the 6 patients with high levels of 7αC4, 5 were also evaluated for PBAs and/or TBAs, finding that high 7αC4 was found, not only in the 2 patients with elevated PBA and/or TBA levels, but also in the 3 patients with normal PBA or TBA levels. Accordingly, 7αC4 showed a moderate correlation with TBAs: 0.542 (p = 0.020), and a negative correlation with PBAs: -0.127 (p = 0.605) and TBAs + PBAs: -0.200 (p = 0.426). In addition, measuring only 7αC4, rather than 7αC4 and 48-h stool collection for BAs, resulted in a 49% savings, with respect to those clinical tests.

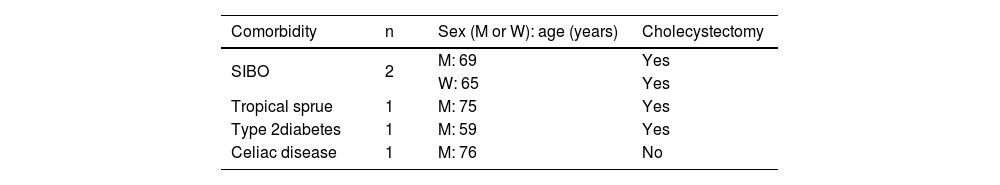

BAM in patients with cholecystectomy and diarrhea of functional originThe frequency of BAM detected by 7αC4 was higher in patients with previous cholecystectomy: 5 of the 22 patients (22.7%), compared with those without it: only one of the 26 patients (3.8%), p = 0.049. In addition, of the 21 patients with IBS-D, functional diarrhea, or other DGBIs with concomitant diarrhea, only one had BAM, according to the tests analyzed, for a prevalence of 4.8% of bile acid diarrhea (BAD) and said patient with BAM, a 78-year-old man, also had a history of cholecystectomy. Furthermore, 5 of the 6 patients with BAM detected by high 7αC4 levels had other comorbidities, and 4 of them also had previous cholecystectomy (Table 2).

Comorbidities that can produce chronic diarrhea in patients with BAM.

| Comorbidity | n | Sex (M or W): age (years) | Cholecystectomy |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIBO | 2 | M: 69 | Yes |

| W: 65 | Yes | ||

| Tropical sprue | 1 | M: 75 | Yes |

| Type 2diabetes | 1 | M: 59 | Yes |

| Celiac disease | 1 | M: 76 | No |

M: man; SIBO: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (clinical suspicion based on the presence of duodenal diverticulum); W: woman.

The present study conducted at a specialized clinic for gastrointestinal motility and DGBIs in Mexico City confirmed that 7αC4 moderately correlated with TBAs and could be elevated despite normal PBAs and/or TBAs, thus making it a useful biomarker for BAM screening. In addition, using only a 7αC4 test, instead of the combination of 7αC4 and 48-h fecal BAs, signified an important savings of 49%, regarding the expenses involved in investigating BAM.

Our data on the usefulness of serum 7αC4 in clinical practice are supported by several studies. When comparing BAM screening using serum biomarkers and 48-h fecal BAs, both serum 7αC4 and FGF-19 exhibited high negative predictive values and specificity, at 79%/83% and 78%/78%, respectively.24 As reported by some authors, the clinical effectiveness of the serum 7αC4 test showed that it could detect BAM with 90% sensitivity, 79% specificity, a negative predictive value of 98%, and a positive predictive value of 74%, when compared with the 75SeHCAT test, particularly in cases where the half-life remaining in the body was ≤ 1.2 days.25 The significant high negative predictive value of the 7αC4 test enhances its potential as an effective screening tool for excluding BAM. This is particularly important, when ruling out BAM in patients with functional diarrhea or IBS-D.

In a meta-analysis, Valentin et al.12 reported a considerable diagnostic yield for serum 7αC4 of 0.171% (95% CI: 0.134-0.217), compared with the gold standard 75SeHCAT test of 0.308% (95% CI: 0.247-0.377). Another systematic review conducted by Lyutakov et al.20 identified 87.32% sensitivity and 93.2% specificity for the 75SeHCAT test, when diagnosing BAM. However, this was followed by 85.2% sensitivity and 71.1% specificity for serum 7αC4 and 66.6% sensitivity and 79.3% specificity for total fecal BAs.

In contrast to the 75SeHCAT test, which demands multiple visits and specialized nuclear medicine equipment, serum 7αC4 is a straightforward blood test that only requires a standardized sample collection time.25 It involves no radiation and when assessed against potential covariates, 7αC4 was found to be non-dependent on age, sex, or serum cholesterol.25 A drawback of 7αC4 testing is that a specific technique (Tandem Mass Spectrometry) and specialized personnel are required for its quantification. Other disadvantages are that false positive or false negative 7αC4 results may occur in patients with liver disease, in patients taking medications that alter BA production, such as statins, or in individuals with an altered circadian rhythm, given that serum 7αC4 has diurnal variations.26 Additionally, the test’s usefulness is still relatively limited, and it is not known whether age, emotional states, or environmental variables, such as work shift or jetlag, may alter the circadian rhythm, and consequently, BA synthesis.25 Although serum 7αC4 is unlikely to replace 75SeHCAT as the gold standard, it can be employed as an initial and useful biomarker to rule out the presence of BAM in patients with chronic diarrhea or bloating and/or distension that are presumed to be related to BAM. This can ultimately improve both the diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of patient care, especially considering the limitations of 75SeHCAT test availability and the fact that it is time-consuming, expensive, and involves radiation exposure.27 Furthermore, measuring fecal BA excretion through PBA and/or TBA levels can be cumbersome because patients are non-compliant with those kinds of tests, as well as difficult for many conventional laboratories to process.28 More recently, to simplify the 48-h stool collection, a single stool BA measurement in BAD and IBS-D has been proposed. The percentage of PBAs in a single stool sample, demonstrated an odds ratio of 3.06 (95% CI: 1.35-7.46) for distinguishing BAD from IBS-D (p = 0.01), whereas the numerical difference in fecal TBA concentration was borderline. In addition, there was a significant correlation of serum 7αC4 with the percentage of primary BAs (Spearman Rho: 0.284, p < 0.001) and a trend toward correlation with total BA concentration (Spearman Rho: 0.132, p = 0.095) in a single stool. With those results, the authors suggested that measurement of the percentage of PBAs could be a useful adjunct to serum measurements and should be tested in a combined model for the diagnosis of BAD.29 Even though the proposed combination of serum 7αC4 with a single stool sample for BA measurements may eliminate the inconveniences involved in 48-h stool collection, it is still an expensive test for patients.

We found only one case of BAM (BAD) in the 21 patients with IBS-D or functional diarrhea, possibly due to a lack of clinical suspicion of BAM. In fact, this is in accordance with the abovementioned study by Lupianez-Merly et al.,29 which now differentiates BAD from IBS-D. Moreover, Wong et al.30 demonstrated that serum 7αC4 also correlated with TBA concentration in stools and stool weight, supporting our findings of the moderate correlation between 7αC4 and TBA levels.

The fact that we observed BAM in two patients with SIBO, one with tropical sprue, and both with diabetes mellitus, is an indication that BAM can coexist with other causes of chronic diarrhea or may be related to their pathophysiology. For example, gut bacteria, mainly Clostridiales, convert primary BAs to secondary BAs, whereas BAs can directly or indirectly shape the gut microbiota through antimicrobial effects and play an important role in the innate immune response. In fact, unconjugated serum BA levels have also been found in patients with SIBO.31

In type 2 diabetes mellitus, high serum levels of 7αC4 and BAM have also been reported, especially among patients with diabetic neuropathy.32–33 Furthermore, in patients with type 2 diabetes, metformin has been related to BAM. In patients taking metformin, the therapeutic inhibition of the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT) in the terminal ileum reduces glucose levels but also reduces the circulation of BAs, consequently elevating 7αC4 levels.34 Therefore, BAM can contribute to diabetic diarrhea. Notwithstanding, continuous research on BAM in the context of functional diarrhea and/or IBS-D is required, as BAD may constitute an independent entity with a specific treatment.35

The current study has certain limitations. First, it was conducted on a small group of patients but corresponds to all of the patients that underwent tests for studying BAM, at a clinic in Mexico. Second, the small number of patients may explain why we identified only one case of BAD in those with functional diarrhea. However, the majority of patients with BAM had also been previously cholecystectomized, which could explain the presence of BAD. Third, not all patients were investigated with both 7αC4 and 48-h stools for BAs. This was related to the previously mentioned fact that the 48-h stool collection involves a logistical limitation and an economic burden for patients. Fourth, our study patients came from a private clinical setting and could afford the tests out-of-pocket or had insurance reimbursement. An alternative to this expensive testing, is a therapeutic trial with cholestyramine, the only treatment for BAD that is available in Mexico. Nevertheless, cholestyramine is not well-tolerated by many patients and at times becomes scarce in the Mexican market. However, the concordance of our results with those from Wong et al.30 and Lupianez-Merly29 supports 7αC4 testing, and implementing the technique for its quantification in local clinical laboratories would further decrease the diagnostic cost of BAD.

In conclusion, we found serum 7αC4 to be a reliable test for BAM screening. Even though it is still an expensive test and is not yet available in Mexico, sending the samples abroad for their quantification results represents an average savings of 49%, in comparison to its combination with 48-h stool testing for BAs. The data obtained from this study suggest that 7αC4 should only be requested when patients presenting with chronic diarrhea compatible with functional diarrhea do not respond to the usual treatments, a setting in which ruling out BAD is important for therapeutic purposes.

Financial disclosureMSW is funded by the Research Division of the Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).

GMD, ZMGS, and ADS: nothing to declare.

CL and RB: worked at Biomédica de Referencia, the Clinical Lab that collected the samples to be shipped to the US for analysis.

MSW: is on the Advisory Council of Daewoong South Korea, Gemelli Biotech Inc, Moksha 8 Mexico, and Pro.Med.CS. Praha A.S.; he is a speaker for Alfa Sigma Mexico, Armstrong Mexico, Carnot, Daewoong South Korea, Ferrer Mexico/Central America, Medix Mexico, Megalabs Ecuador, Tecnofarma Colombia/Bolivia; he provides educational materials for Moksha 8.

See related content in DOI: 10.1016/j.rgmxen.2025.01.002, Remes-Troche J.M. Bile acid malabsorption (BAM): A rarely suspectedcause of chronic diarrhea – Towards an efficient andeconomic diagnosis. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2025;90:167–168.