Acute appendicitis stands out as one of the most frequent surgically-treated diseases. Risk scales for acute appendicitis, such as the Alvarado and AIR scoring systems, show good diagnostic yield. The aim of our study was to compare the predictive capacity between the Alvarado and Air scores in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted on patients that underwent appendectomy due to suspected acute appendicitis, confirmed by histopathology. The predictive capacity of the Alvarado and Air scores was evaluated through an ROC curve analysis, determining the area under the ROC curve. The STROBE checklist was utilized.

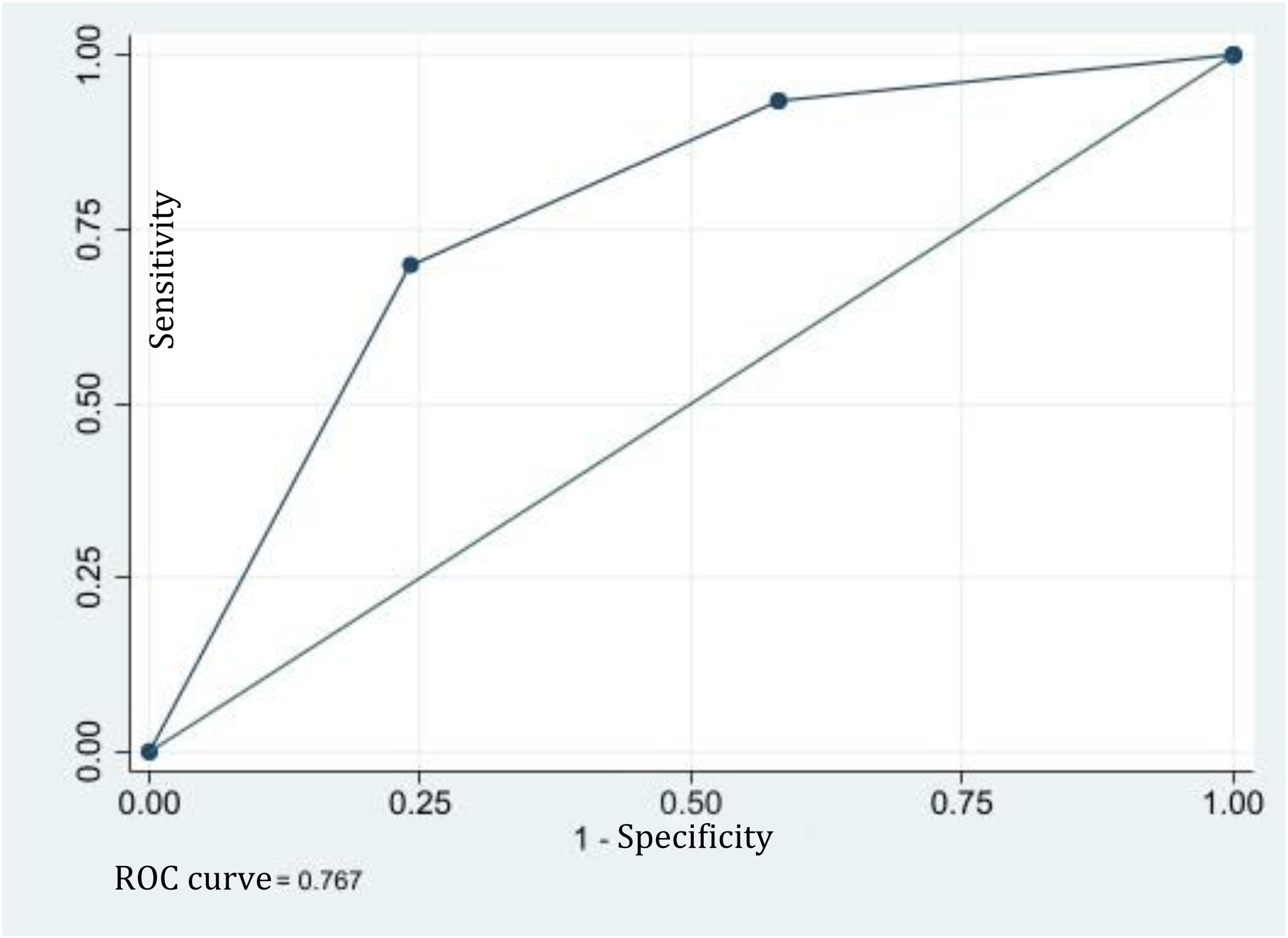

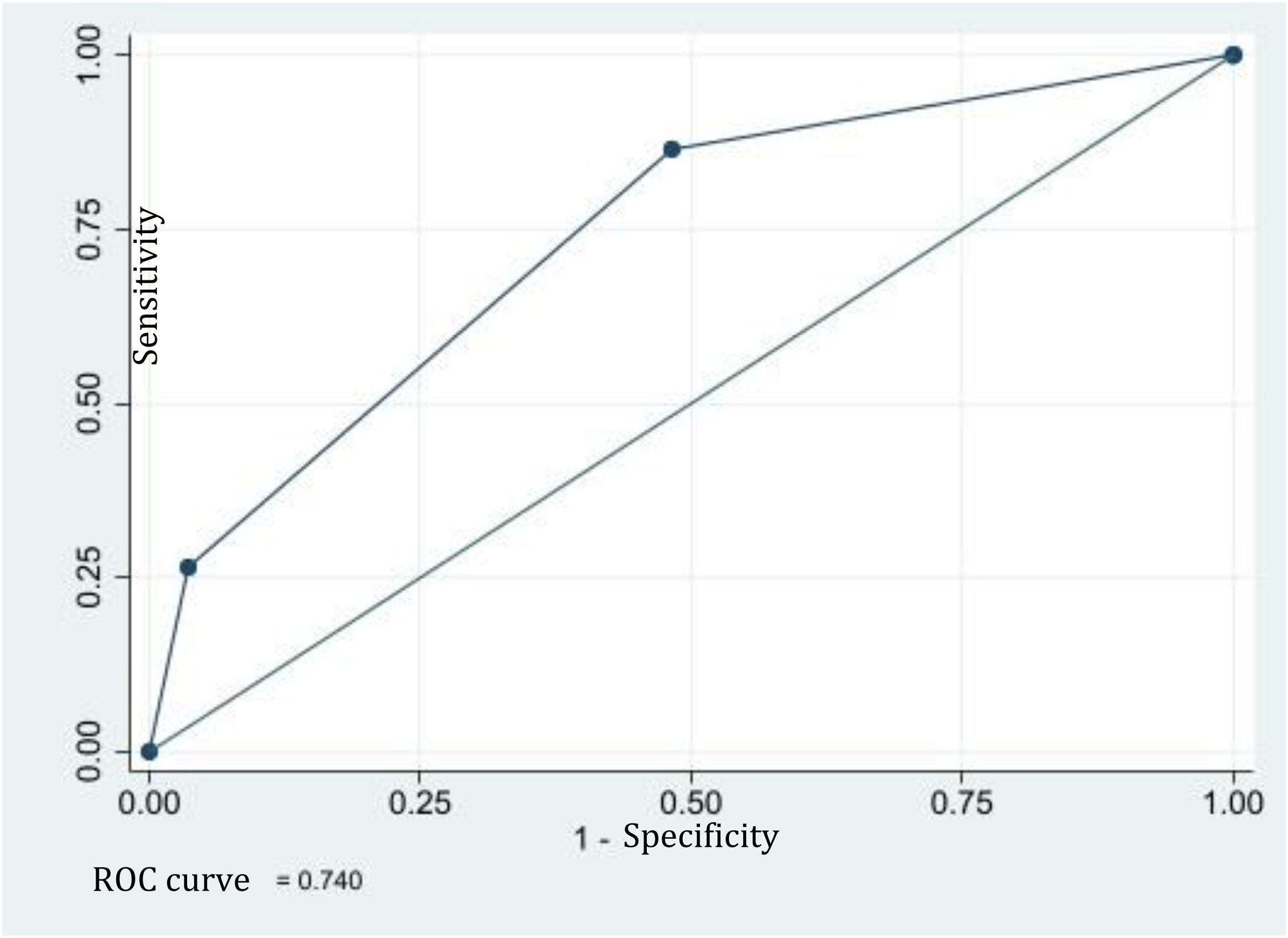

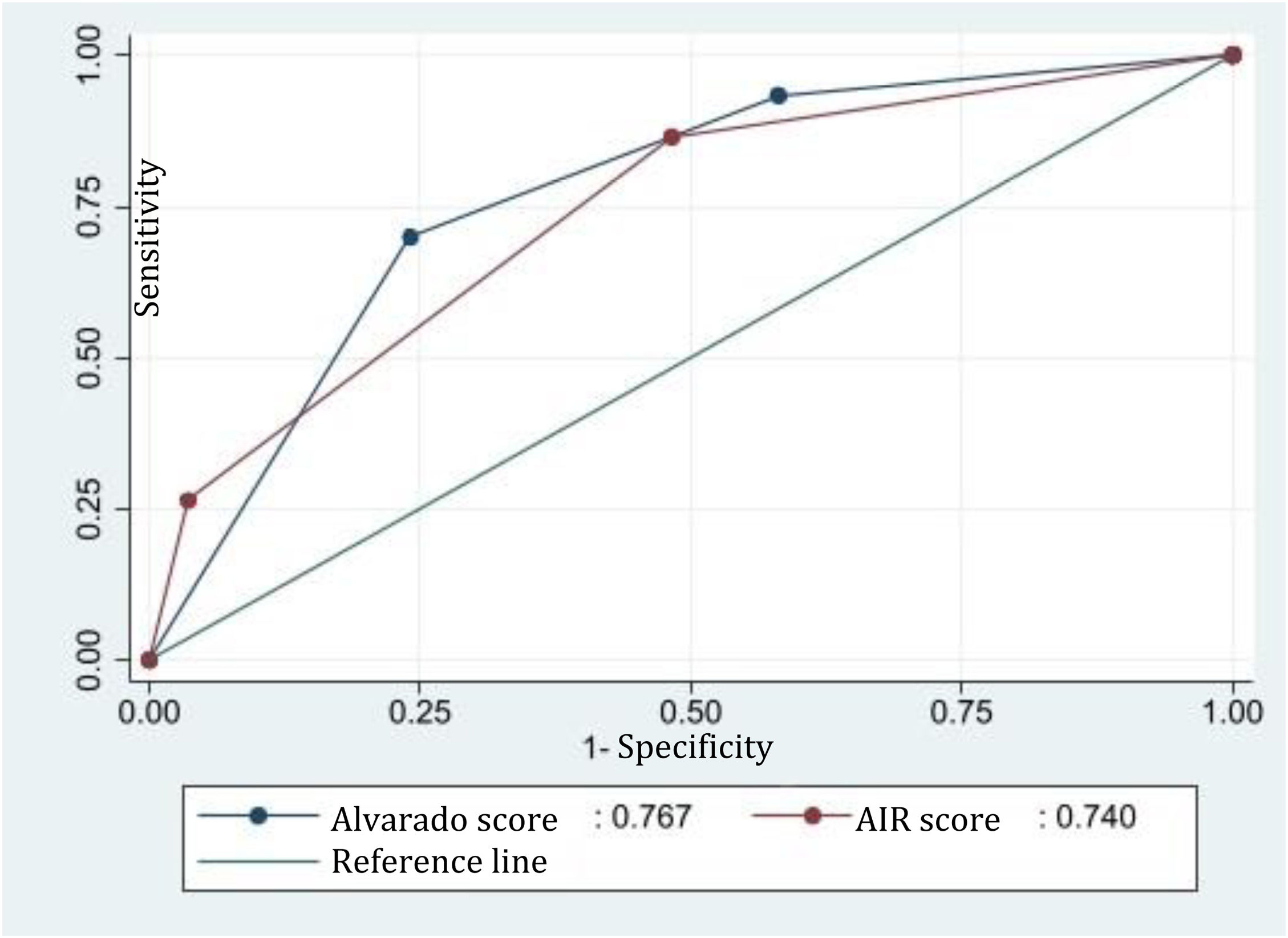

ResultsA total of 358 patients with clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis were included, 51% of whom were men (183/358). Median patient age was 36 years (IQR: 24−46). The ROC curve of the Alvarado score was 0.767 (95% CI: 0.716−0.818), and with a cutoff point of 0−4, had 78% sensitivity and 84% specificity. The AIR score had a ROC curve of 0.741 (95% CI: 0.691−0.788), and with a 0−4 cutoff point, 87% sensitivity and 56% specificity. There was no statistically significant difference between the two scores (p = 0.266).

ConclusionThe Alvarado and AIR scores have a similar predictive capacity for acute appendicitis. The low cutoff points of the risk scales are related to greater diagnostic sensitivity of the disease.

La apendicitis aguda destaca como una de las patologías quirúrgicas más frecuentes. El uso de escalas de riesgo para la apendicitis aguda como la escala de Alvarado y AIR muestran un bien rendimiento diagnóstico. El objetivo del artículo es comparar la capacidad predictiva de las escalas de Alvarado y AIR en el diagnóstico de apendicitis aguda.

MétodosEstudio de corte transversal con pacientes sometidos a apendicectomía por sospecha clínica de apendicitis aguda, se confirmó el diagnostico por histopatología. Se evaluó la capacidad predictiva de las escalas Alvarado y AIR mediante análisis de ROC determinando el área bajo la curva (curva ROC). Este estudio utilizo la lista de verificación STROBE.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 358 pacientes con sospecha clínica de apendicitis aguda, el 51% eran hombres (183/358) y la mediana de edad fue 36 años (RIC:24−46). La curva-ROC de la escala de Alvarado fue 0.767 (ICdel95%:0.716−0.818), y con un punto de corte de 0 a 4 mostró una sensibilidad de 78% y especificidad de 84%. La escala AIR mostró una curva ROC de 0.741 (IC del 95%: 0.691−0.788), y con un punto de corte de 0 a 4 mostro una sensibilidad de 87% y especificidad de 56%. Al comparar ambas escalas, no se observó una diferencia significativa (p = 0.266).

ConclusiónLas escalas de Alvarado y AIR muestran una capacidad predictiva similar para la apendicitis aguda. Los puntos de corte bajos en las escalas de riesgo se relacionan con una mayor sensibilidad diagnóstica de la enfermedad.

Acute appendicitis stands out as one of the most frequent diseases requiring surgery, with an incidence that varies from 90 to 100 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, and it presents an 8.6% risk in men and a 6.7% risk in women.1 It has an annual mortality rate of 1–4%, whereas the morbidity rate can reach up to 30%.1,2The initial diagnostic focus of acute appendicitis is made by means of risk scoring systems that integrate clinical information, laboratory test results, and diagnostic imaging results, to improve accurate prediction of the disease. Nevertheless, the rate of appendectomies with no histologic evidence of appendicitis or false positives continues to be above 6%.1,2

Risk scoring systems for acute appendicitis include the Alvarado score, which has 86% specificity and 50–72% sensitivity.3 Similar data are reported for the appendicitis inflammatory response (AIR) score, which incorporates C-reactive protein levels for improving its performance, reaching 78.4% sensitivity and 97% specificity.4,5 However, there is limited medical evidence comparing the two scores.6,7 The aim of the present study was to compare the Alvarado and AIR scores with the histopathologic analysis, to determine their respective accuracy in diagnosing acute appendicitis.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted at a single tertiary care hospital in Colombia, to evaluate the predictive capacity of the Alvarado and AIR scores for acute appendicitis, during a ten-month time frame, from November 2020 to September 2021. The study utilized the STROBE checklist.

Eligibility criteriaThe inclusion criteria were patients above 18 years of age, with clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis, and a disease course of fewer than 7 days from symptom onset. The exclusion criteria were patients with other intra-abdominal inflammatory/infectious diseases, patients with no histopathologic reports, and individuals that experienced chronic abdominal pain. All the data were collected from the clinical history of each patient and placed in a secure database.

We used 80% healthy individuals, 20% sick individuals, 80% sensitivity and specificity, and a 1.96 margin of error (alpha value) to calculate the sample size, which was estimated at 325 patients.8

Clinical variablesThe variables for the Alvarado and Air scores were calculated. Clinical and surgical management was carried out according to individual risk. Computed tomography or ultrasound studies were performed for patients with intermediate risk, and high-risk patients underwent emergency surgical intervention. The extirpated appendices from the patients that underwent surgery were evaluated histopathologically, based on microscopic findings, to confirm the diagnosis. The final histopathologic analysis determined a positive diagnosis, and the decision to operate was made by the surgeon.

Statistical analysisAll the analyses were performed using the Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, USA) program. The data were automatically obtained through an electronic collection form that was then transferred to an Excel calculation sheet for verification by the research group, to identify any transcription error and make corrections. The qualitative variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, and the quantitative variables were expressed through mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, according to their distribution. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) in identifying acute appendicitis confirmed by histopathology were calculated for the Alvarado and AIR scores. The predictive validity of the scores was evaluated through the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, determining the area under the ROC curve, with a 95% confidence interval. The calculated ROC curves were then compared using the DeLong test.9

ROC curve interpretation was as follows: 0.50 indicated the absence of discriminating capacity; 0.51 to 0.60 indicated almost no discriminating capacity; 0.61 to 0.69 indicated poor discriminating capacity; >0.7 to 0.8 indicated acceptable discriminating capacity; >0.80 to 0.90 indicated excellent discriminating capacity; and >0.90 indicated outstanding discriminating capacity.9 Statistical significance was set at a p value <0.05.

Ethical considerationsOur research meets the current bioethical research regulations and was authorized by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad de La Sabana (Code: MEDEsp-41-2020). The authors declare that this article contains no personal information that could identify the study participants. All patients included in the study accepted and signed statements of informed consent, given the prospective, observational nature of this study.

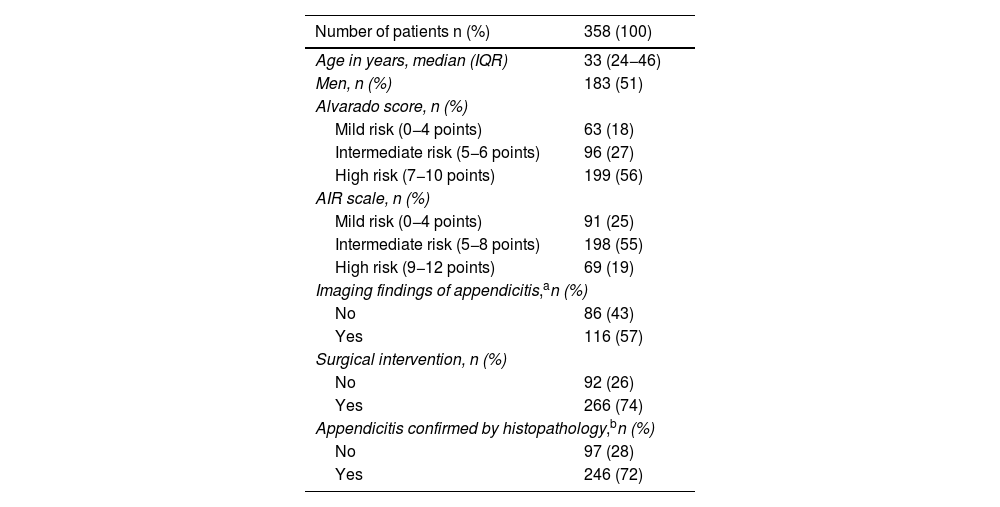

ResultsA total of 358 patients with clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis were included in the study. Fifty-one percent of the patients were men (183/358), and the median patient age was 36 years (interquartile range: 24−46). Table 1 shows the general population characteristics.

Demographic analysis of the study population.

| Number of patients n (%) | 358 (100) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 33 (24−46) |

| Men, n (%) | 183 (51) |

| Alvarado score, n (%) | |

| Mild risk (0−4 points) | 63 (18) |

| Intermediate risk (5−6 points) | 96 (27) |

| High risk (7−10 points) | 199 (56) |

| AIR scale, n (%) | |

| Mild risk (0−4 points) | 91 (25) |

| Intermediate risk (5−8 points) | 198 (55) |

| High risk (9−12 points) | 69 (19) |

| Imaging findings of appendicitis,an (%) | |

| No | 86 (43) |

| Yes | 116 (57) |

| Surgical intervention, n (%) | |

| No | 92 (26) |

| Yes | 266 (74) |

| Appendicitis confirmed by histopathology,bn (%) | |

| No | 97 (28) |

| Yes | 246 (72) |

AIR: Appendicitis Inflammatory Response; IQR: interquartile range.

The ROC curve of the Alvarado score was 0.767 (95% CI: 0.716−0.818) for predicting the diagnosis of acute appendicitis (Fig. 1). Low risk, or a cutoff point of 0−4, showed 78% sensitivity, 84% specificity, a PPV of 95%, and a NPV of 49%. High risk, or a cutoff point of 7−10, showed 71% sensitivity, 83% specificity, a PPV of 92%, and a NPV of 48%.

The ROC curve for the AIR score was 0.741 (95% CI: 0.691−0.788) (Fig. 2). Low risk, or a cutoff point of 0–4, showed 87% sensitivity, 56% specificity, a PPV of 61%, and a NPV of 16%. High risk, or a cutoff point of 9–12, showed 27% sensitivity, 97% specificity, a PPV of 96%, and a NPV of 67%.

There were no statistically significant differences between the Alvarado score and the AIR score (p = 0.266) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThe diagnosis of acute appendicitis is a challenge. Different diagnostic scales have been developed for evaluating the risk for presenting this condition, in the context of acute abdominal pain. Said tools include the Alvarado score and the AIR score and they have similarities in their capacities to predict the disease.4,5,10–14 Low cutoff points of risk scores are related to greater diagnostic sensitivity for the disease. In the present study, the AIR score showed a higher specificity and PPV, compared with the Alvarado score, with a high-risk cutoff point. In addition, in the cases at high risk for acute appendicitis, the PPV increased considerably, providing greater confidence in the diagnosis.

These finding can be discussed, in light of the available evidence. Kollár et al.5 compared the discriminating capacity of the AIR score with both the Alvarado score and the clinical impression of an experienced surgeon. The results showed that the risk scores and clinical judgement of an experienced surgeon had similar accuracy for ruling out appendicitis. The AIR score also showed excellent specificity in patients at high risk for presenting with acute appendicitis, surpassing both clinical judgement and the Alvarado score, results that coincide with the findings of our study.10–12

In observational studies, including ours, there is low sensitivity in patients at high risk for acute appendicitis, according to the AIR score. This is due to the fact that a significant number of patients are stratified in the medium probability group.13 Therefore, the use of diagnostic imaging studies is necessary, to confirm and support the clinical diagnosis. The use of risk scores can be beneficial in the diagnostic approximation of acute appendicitis. Nevertheless, employing them as complements to expert clinical evaluation, physical examination, and diagnostic imaging is essential.13,14

Even though our study did not include the analysis of diagnostic images as a clinical result, our findings support those described in the literature, in which the PPV of the two scores stands out as more precise in patients classified as high-risk for acute appendicitis.14,15 Noori et al.4 compared the discriminating capacity of the AIR and Alvarado scores with computed tomography. Cutoff points ≥4 to ≤6 for the Alvarado score showed lower sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values, compared with diagnostic imaging. However, computed tomography had a diagnostic yield comparable to that of the Alvarado and AIR scores of ≤4 and ≥7, respectively.

A limitation of our study was the fact that it was conducted at a single center and that pediatric and pregnant populations were excluded, which could be an obstacle for extrapolating our results to the identification of acute appendicitis in those population groups. The prospective collection of clinical information and the representative sample size of the population have enabled us to obtain solid results. We believe that our findings can significantly contribute to the approach to and diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Nevertheless, we recognize the importance of carrying out additional studies, as well as comparing the scores we evaluated, with other existing scores for this disease, to broaden and strengthen our results.12–16

ConclusionThe Alvarado and AIR scores showed a similar predictive capacity for acute appendicitis. However, the AIR score had greater specificity and a higher PPV, compared with the Alvarado score, when a high-risk cutoff point was utilized. These scores can be useful at the emergency service for the identification of acute appendicitis.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll the authors participated in the study conception and design; data acquisition; result analysis, interpretation, and review; and the writing and final review of the article.

Financial disclosureThis project received funds from the Universidad de La Sabana (Code: MEDEsp-41-2020).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

To the University of La Sabana.