Rumination syndrome (RS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by effortless and repetitive regurgitation of ingested food from the stomach to the oral cavity, followed by either re-swallowing or spitting.1 It is produced by an increase in the intragastric pressure that is generated by a voluntary, unintentional contraction of the abdominal wall.1 RS appears to be underdiagnosed due to a lack of awareness among physicians, and it may be more common in females.2 It was first described in association with impaired mental development, more in children than in adults,3 but is now recognized as a distinct clinical entity unrelated to mental status or age. Most patients have symptoms within 10min of finishing a meal.2 Regurgitation is the most common symptom, which is why gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the main differential diagnosis. Reflux is often described as tasting like the recently ingested food. Overt pain is not often described, but postprandial symptoms, such as dyspepsia, have been reported in up to 50% of patients.2 Weight loss has been observed in approximately 40% of patients, but complications such as electrolyte disturbances and malnutrition are much less common.2 Patients are often discouraged by prolonged symptoms with no improvement after GERD therapy. The diagnosis of RS in adults is based on the ROME IV criteria. Although clinical suspicion is important, postprandial esophageal high-resolution impedance manometry (HRIM) supports the diagnosis. It shows gastric pressurizations exceeding 30mmHg that are associated with simultaneous upper and lower esophageal relaxation that is apparently closely related to the return of the ingested material into the esophagus and mouth, as well as to patient symptoms.1 Variants of rumination have been identified and can be differentiated by specific patterns.4 Increase in intragastric pressure followed by regurgitation is the most important characteristic distinguishing rumination from other disorders, such as gastroesophageal reflux. Treatment should be interdisciplinary and based on 3 points: an explanation of the condition and its underlying mechanism, diaphragmatic breathing, and visual feedback on the electromyogram (EMG) activity of the relevant muscles. Regarding the pharmacologic approach, drugs that affect the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) resting tone and suppress transient LES relaxations, such as baclofen and a GABA-B agonist, could potentially have a therapeutic role. Finally, fundoplication has been suggested for refractory cases.5

Gastroparesis is characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Nausea and vomiting are the classic symptoms.6 The pathogenesis may result from autonomic neuropathy, affecting excitatory and inhibitory intrinsic nerves or the interstitial cells of Cajal, or from myopathic diseases. The most common causes are neuropathic disorders such as diabetes, post-vagotomy surgery, and connective tissue diseases like scleroderma.7 When the pathology is not justified by a systemic disease, it is called “idiopathic gastroparesis”. The mainstays of treatment are restoration of hydration, electrolytes, and nutrition, and pharmacologic treatment with prokinetics and antiemetics. In more severe cases, enteral feeding, percutaneous gastrostomy for draining the stomach, or gastric electrical stimulation may be considered. More recently, gastric peroral endoscopic pyloromyotomy has emerged as a novel endoscopic technique to treat refractory gastroparesis.8

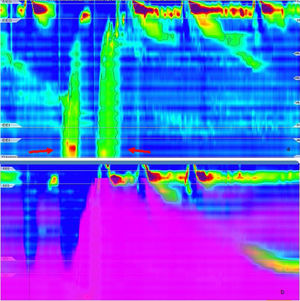

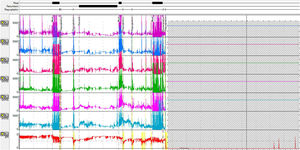

We present herein a 31-year-old female patient with long-term postprandial regurgitation and early satiety for more than 2 years. She had several previous hospitalizations with enteral feeding requirements due to malnutrition. The patient had no history of eating disorders, but her family environment was conflictive. Complementary studies (brain CT and MRI, esophageal barium swallow, intestinal MRI) identified no abnormalities. Upper esophageal endoscopy revealed food content in the stomach after 12h of fasting. A conventional esophageal manometry diagnosed hypotensive LES with normal esophageal motility. We performed a HRIM that showed hypotensive LES and ineffective esophageal motility (Chicago classification v.3). The solid meal test (200g of rice) produced several episodes of gastric pressure increments higher than 30mmHg with regurgitation (R waves) and re-swallowing of the gastric contents with no vomiting or nausea (Fig. 1a and b). Ambulatory reflux monitoring showed several episodes of postprandial regurgitation. The registry was incomplete (9h) due to spontaneous catheter migration (Fig. 2). Because there were dyspeptic symptoms, we performed an esophagogastric transit study using scintigraphy (280kcal) that showed food content retention > 30%, 4h post-ingestion. Connective tissue diseases, diabetes, and pharmacologic causes of gastroparesis were ruled out. TSH levels were normal.

a) High-resolution impedance manometry after a solid meal test. Primary rumination: an increase in gastric pressure is followed by gastric content flow. Peak gastric pressure is observed during the retrograde gastric content flow and subsequent relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter is observed. R waves (arrows) during solid meal intake. b) Impedance during high-resolution manometry: inadequate bolus transit.

The patient had received several courses of double PPI schemes (omeprazole, pantoprazole) that were unsuccessful. She recently started behavioral therapy and is receiving prokinetics to treat the gastroparesis symptoms, with partial response. We interpret the case as RS associated with idiopathic gastroparesis.

Finally, RS diagnosis is a challenge in itself, not only because its most important differential diagnosis is the highly prevalent GERD, but also because the therapeutic approach is difficult, and the results are not always encouraging.

Gastroparesis has an increased clinical burden and affects quality of life.9 Camilleri et al. proposed that the differential diagnoses are functional dyspepsia, GERD, RS, and cannabinoid hyperemesis.10 Visceral sensation is detected by vagal and spinal afferent pathways, with the former synapsing on the nodose ganglion.11 After each meal, there is a reduction in the vagal tone and gastric fundus distension relaxes the LES through a vagal mechanism.11 Said mechanism could explain the motility disorder we found in our patient. Late recognition implies serious deterioration in nutritional status and quality of life, thus early diagnosis is important. We were unable to establish a causality association but there could be a common pathophysiologic mechanism behind the 2 disorders.

Financial disclosureThere are no funding sources.

Author contributionsJulieta Argüero: carried out the literature review and drafting of the manuscript.

Julieta Argüero and Virginia Cano: made the diagnosis and monitored the patient.

Demetrio Cavadas and Mariano Marcolongo: performed the critical review of the manuscript.

Ethical considerationsThe patient described in the present scientific letter gave her consent to have her case reported, both in journals and at scientific meetings and multidisciplinary case discussion meetings. The manuscript was written in compliance with the standards established in the Declaration of Helsinski (v. 2013).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Argüero J, Cano-Busnelli V, Cavadas D, Marcolongo M. Síndrome de rumiación y gastroparesia: ¿entidades ligadas? Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2021;86:205–207.