The low FODMAP diet eliminates carbohydrates and fermentable alcohols because they are not absorbed by the intestine, but are fermented by the microbiota, causing bloating and flatulence.

AimsTo evaluate the clinical response to the low FODMAP diet in patients with the different clinical subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Materials and methodsattended to at the Gastroenterology Department in 2014 that were diagnosed with IBS based on the Rome III criteria were included in the study. They were managed with a low FODMAP diet for 21 days and their response to the symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and stool form pre and post-diet were evaluated through the visual analogue scale, Bristol scale, and patient overall satisfaction. The results were analyzed by means, 95% CI, and the Student's t test.

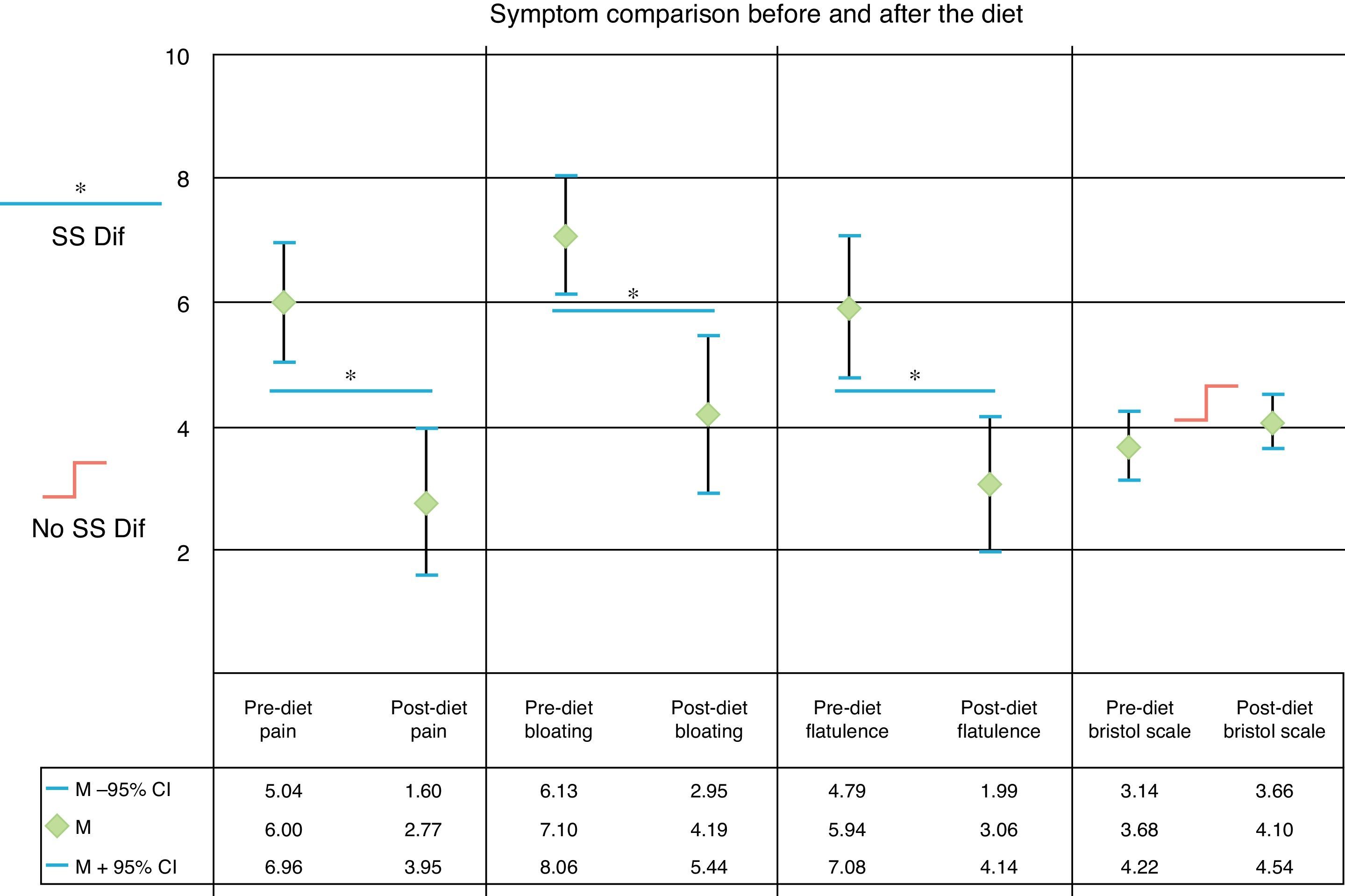

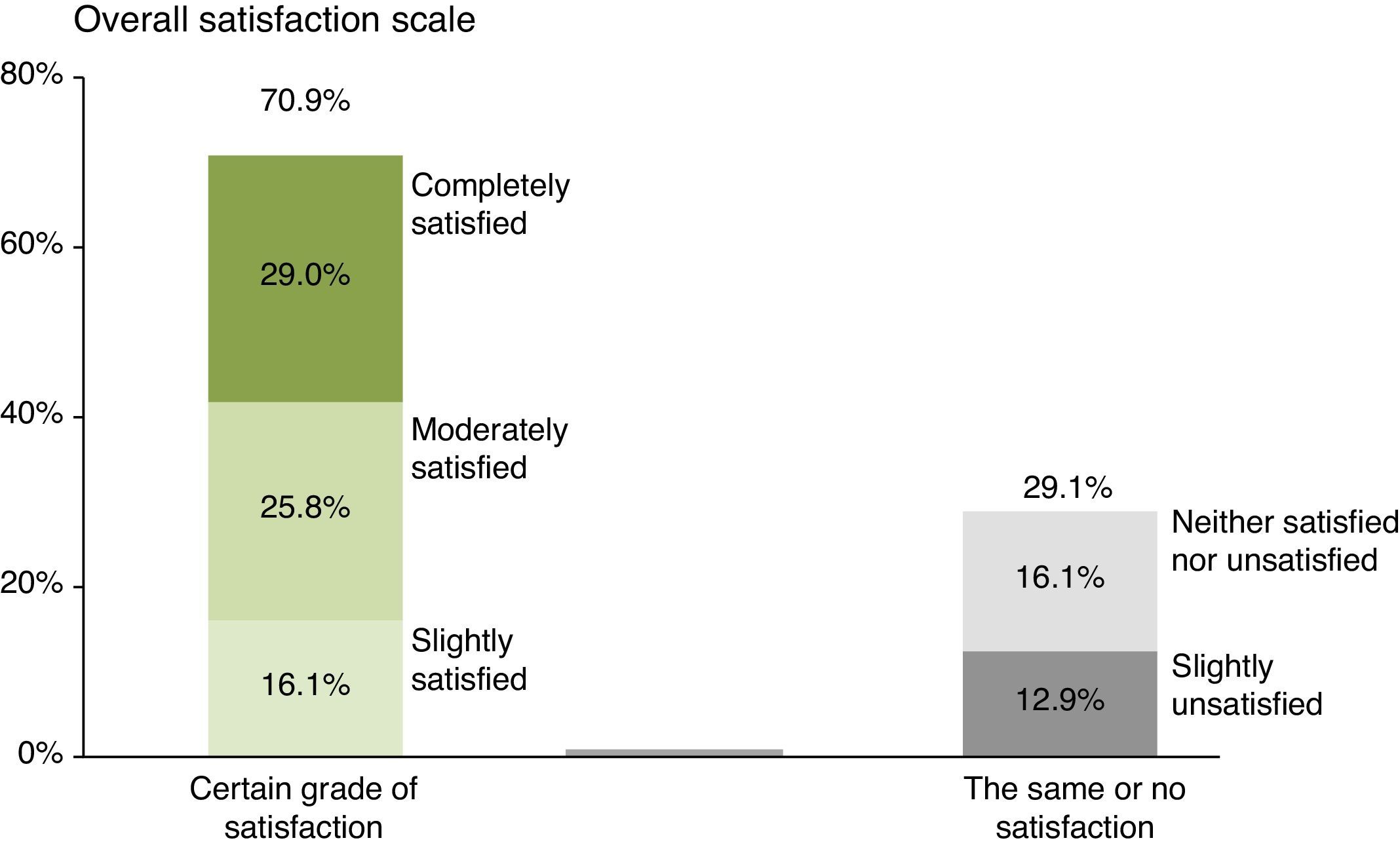

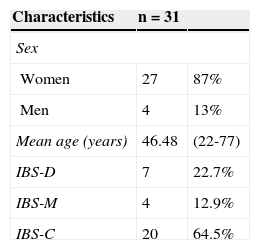

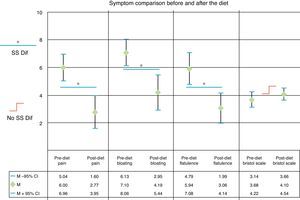

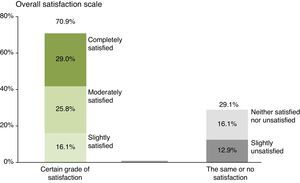

ResultsOf the 31 patients included in the study, 87% were women and the mean age was 46.48 years. Distribution was: IBS-C 64.5%, IBS-D 22.6%, and IBS-M 12.9%. The score for pain was 6.0 (95% CI 5.04-6.96) and the post-diet score was 2.77 (95% CI 1.60-3.95) (P<.001). The score for bloating was 7.10 (95% CI 6.13-8.06) and the post-diet score was 4.19 (95% CI 2.95-5.44) (P<.001). The score for flatulence was 5.94 (95% CI 4.79-7.08) and the post-diet score was 3.06 (IC95% 1.99-4.14) (P<.001). The pre-diet Bristol Scale result was 3.68 (95% CI 3.14-4.22) and the post-diet result was 4.10 (95% CI 3.66-4.54) (P=.1). The satisfaction percentage was 70.9%.

ConclusionsIn this first study on a Mexican population with IBS, there was significant improvement of the main symptoms, including pain, bloating, and flatulence after treatment with a low FODMAP diet.

La dieta baja en FODMAP elimina hidratos de carbono y alcoholes fermentables porque éstos no son absorbidos por el intestino pero son fermentados por la microbiota provocando distensión y flatulencia.

ObjetivoEvaluar la respuesta clínica en pacientes con síndrome de intestino irritable (SII) en sus diferentes variantes clínicas a la dieta baja en FODMAP.

Materiales y métodosSe incluyó a pacientes de la consulta de Gastroenterología, con diagnóstico de SII sobre la base de los criterios de Roma III en 2014, que fueron manejados por 21 días con dieta baja en FODMAP, evaluando la respuesta de los síntomas de dolor abdominal, distensión, flatulencia y forma de las evacuaciones pre y posdieta con escala visual análoga, escala de Bristol y la satisfacción global. Los resultados fueron analizados con promedios, IC del 95% y t de Student.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 31 pacientes, 87% mujeres. Edad promedio (46.48). La distribución fue: SII-E 64.5%, SII-D 22.6% y SII-M 12.9%. La puntuación para dolor fue 6.0 (IC del 95% 5.04-6.96) y posdieta fue 2.77 (IC del 95% 1.60-3.95) (p < 0.001). Para distensión fue 7.10 (IC del 95% 6.13-8.06) y posdieta 4.19 (IC del 95% 2.95-5.44) (p< 0.001). Para flatulencia 5.94 (IC del 95% 4.79-7.08) y posdieta 3.06 (IC del 95% 1.99-4.14) (p< 0.001). La escala de Bristol predieta fue 3.68 (IC del 95% 3.14-4.22) y posdieta 4.10 (IC del 95% 3.66-4.54) (p = 0.1). El porcentaje de satisfacción fue del 70.9%.

ConclusionesEn este primer estudio en población mexicana con SII se observó mejoría significativa de los principales síntomas incluyendo dolor, distensión y flatulencia tras una dieta baja FODMAP.

Even though many patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) believe that diet is an important part of treatment and a certain amount of success has been obtained with empirical dietary changes, it is only recently that the effect of certain specific modifications in the diet of these patients has been studied.1

The FODMAPs include short chain carbohydrates, such as fructose and lactose, fructo and galacto-oligosaccharides, such as fructans and galactans, and polyhydric alcohols, such as sorbitol and mannitol. The term fructans includes carbohydrates with chains consisting of more than 10 carbons, called inulins.2

The low FODMAP diet excludes fermentable fructans, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyoles.3

It is currently known that these carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the small bowel and when they reach the colon they are fermented, producing gas and bloating. Their symptom-producing mechanism is due to distension, which is a product of their osmotic effect and rapid fermentation, mainly to hydrogen.4

Patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders usually present with complaints related to an excess of intestinal gas, mainly presenting as abdominal bloating and flatulence.5

In recent studies, the low FODMAP diet has been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of IBS patients,1,4–12 but no studies have analyzed the efficacy of this approach in Mexican patients.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the clinical response to the low FODMAP diet in a Mexican population group diagnosed with IBS in any of its clinical subtypes.

MethodsAn experimental, comparative, longitudinal, prospective, clinical study was conducted. It included patients seen at the Gastroenterology outpatient service of the Hospital Juárez de Mexico, within the time frame of March to June 2014, that were diagnosed with IBS and any of its subtypes, using the Rome III criteria: constipation, diarrhea, or mixed. The patients were managed for 21 days with a low FODMAP diet (< 0.50g per meal), based on recommendations published in the medical literature. Symptoms and stool forms before and after the diet were compared and overall satisfaction at the end of the treatment was evaluated. The symptoms analyzed were abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence and they were measured through the visual analogue scale (VAS) that graded symptom severity on a scale from 0 to 10. Stool form was evaluated using the Bristol Scale (BS) (types 1-7). Overall patient satisfaction was evaluated through the 5-option global satisfaction scale (GSS) (completely satisfied, moderately satisfied, slightly satisfied, neither satisfied nor unsatisfied, slightly unsatisfied).

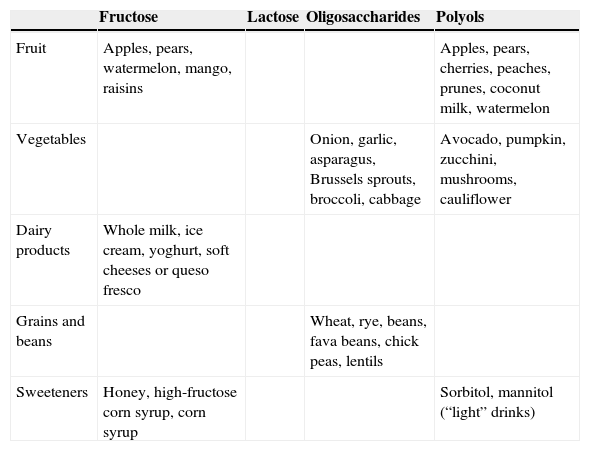

The patients were enrolled at an initial visit, registering one day of their usual diet. They were given appointments every Friday for the first 2 weeks before beginning the low FODMAP to evaluate the baseline VAS and BS. At their second week visit they were given a written diet (Table 1) that included the prohibited foods for the 21-day test period. The patients were told to write down their daily menu, which was analyzed by the researcher at the control interviews.

Foods that are prohibited on the low FODMAP diet.

| Fructose | Lactose | Oligosaccharides | Polyols | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | Apples, pears, watermelon, mango, raisins | Apples, pears, cherries, peaches, prunes, coconut milk, watermelon | ||

| Vegetables | Onion, garlic, asparagus, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, cabbage | Avocado, pumpkin, zucchini, mushrooms, cauliflower | ||

| Dairy products | Whole milk, ice cream, yoghurt, soft cheeses or queso fresco | |||

| Grains and beans | Wheat, rye, beans, fava beans, chick peas, lentils | |||

| Sweeteners | Honey, high-fructose corn syrup, corn syrup | Sorbitol, mannitol (“light” drinks) |

The control of the dietary clinical response was evaluated once a week during the 3 weeks of treatment, with the patient filling out the VAS and BS in the presence of a researcher, as well as registering the meals eaten each week. The GSS was also analyzed at the appointment the final week of treatment.

The VAS was used for the 3 symptoms to be evaluated and the BS was employed for stool forms, as continuous numerical variables. Means were analyzed as measures of central tendency. The difference between measurements before the low FODMAP diet and after the 21 days of its application was analyzed through the 95% confidence interval for numerical variables and the Student's t test for paired samples of a single trend. Both calculations were made using the 2010 Excel program for Mac.

ResultsA total of 31 patients were included in the study, 87% of which were women. The mean age was 46.4 years (range: 22-77). Twenty patients (64.5%) presented with the predominant IBS-C, followed by 7 patients (22.6%) with IBS-D, and 4 patients (12.9%) with IBS-M (Table 2). The mean body mass index of the study patients was 23.81kg/m2 (range: 19.1-29.9kg/m2), mean weight was 59.96kg (range: 49-85kg), and mean height was 1.53 m (1.50-1.75 m). The mean usual caloric intake exceeded 2,800kcal. The patients’ regular diet was high in carbohydrates, flours, and dairy products that included foods such as fruits, juices, and sugared drinks. Dairy intake was at least twice a day and flour intake at least 3 times a day. The mean FODMAP intake was > 300g daily.

The mean score for abdominal pain before the low FODMAP diet was 6 (95% CI = 5.04-6.96) and was 2.77 after the diet (95% CI = 1.6-3.95) (p < 0.001) (fig. 1). A statistically significant improvement was observed in the scores for bloating (7.10 [95% CI 6.13-8.06] to 4.19 [95% CI 2.95-5.44] [p< 0.001]) (fig. 1) and flatulence (5.94 [95% CI 4.79-7.08] 3.06 [95% CI 1.99-4.14] [p< 0.001]) (fig. 1). The mean BS classification before the low FODMAP diet was 3.68 units (95% CI 3.14-4.22) and was 4.10 after the diet (95% CI 3.66-4.54), resulting in a slight improvement in stool form, but with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.1) (fig. 1).

Graph showing the change in abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence evaluated with a 10-unit visual analogue scale and the stool form characteristics according to the Bristol Scale, before and after a 21-day low FODMAP diet.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; M: mean; No SS Dif: no statistically significant difference.

*SS Dif: statistically significant difference p < 0.001.

In relation to overall satisfaction after the low FODMAP diet, 70.9% of the patients had some grade of satisfaction: 16.1% said they were slightly satisfied, 25.8% moderately satisfied, and 29.0% completely satisfied. Of the 29.1% that did not express satisfaction after the low FODMAP diet, 16.1% said they had no change (neither satisfied nor unsatisfied) and 12.9% stated that treatment was unsatisfactory (fig. 2).

Graph showing the grade of overall satisfaction in relation to the gastrointestinal symptoms after 21 days of the low FODMAP diet evaluated with a 5-point scale (5, completely satisfied; 4, moderately satisfied; 3, slightly satisfied; 2, neither satisfied nor unsatisfied; 1, slightly unsatisfied).

The present study sought to evaluate the clinical response in Mexican patients in relation to the most common IBS symptom complaints (abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and altered stool form) after treatment with a low FODMAP diet.

Even though IBS is one of the most frequent conditions confronting the gastroenterologist in daily practice (with a worldwide incidence between 10 and 20% and an incidence in Mexico reported in different studies of 16 to 35%),13,14 treatment continues to be unsatisfactory.4

An important number of patients state that certain foods trigger symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence. Nevertheless, treatments focused on diet are not a central part of therapy, mainly due to the lack of evidence supporting the fact that the exclusion or reduction of a certain food would result in improvement.4

In recent years, attention has been given to different dietary modifications in these patients, and one of the diets that has shown more efficacy is the diet low in fermentable fructans, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (the low FODMAP diet).

The first study showing the benefit of this dietary approach was a retrospective analysis conducted on selected patients with IBS and fructose and fructans malabsorption. It was followed by a double-blind, randomized study with a later challenge using fructose and fructans, alone or combined, in the patients that had responded to the diet. Symptoms returned in 4 out of 5 patients with the re-introduction of fructans and in one out of 5 patients in the placebo group. The symptoms were dose-dependent and the effects of fructose and fructans were synergic.1 In a recent controlled and crossover study in Australia on 30 IBS patients, Halmos et al.4 found that the low FODMAP diet efficaciously reduced functional gastrointestinal symptoms, compared with a typical Australian diet. In another study, Azpiroz et al.5 evaluated the response to a low FODMAP diet in patients with flatulence and found significant improvement, with a reduction of gas, compared with the standard Mediterranean diet, and they reported immediate benefits in relation to digestive, cognitive, and emotional aspects of the patients. A study by De Roest et al. compared the response of symptoms such as abdominal pain and flatulence and found a 76% response in all the variables studied.9

In our study, we observed significant improvement in the most frequent IBS symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence, with an overall patient satisfaction of 70.9%. These results concur with those reported in the current literature. However, when evaluating stool form, we found no significant improvement after treatment. Therefore we cannot recommend this approach if the aim is to improve stool form evaluated through the patient-reported BS.

Among the strengths of our study is the fact that it was conducted at a referral hospital that attends to patients from different geographic areas of the country (mainly Mexico City, the States of Mexico, Hidalgo, and Oaxaca), conforming a more representative sample of the Mexican population. Nevertheless, it is important to carry out a study with a larger sample that includes other areas of Mexico in order to confirm our findings.

This is the first study analyzing the low FODMAP diet in a Mexican population showing that this therapeutic approach appears to be useful in our environment for treating IBS symptoms related to abdominal pain or discomfort, but not for those associated with changes in bowel habit.

In conclusion, the therapeutic approach based on a low FODMAP diet in a Mexican population is effective for the management of abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence associated with IBS.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and were in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center in relation to the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pérez y López N, Torres-López E, Zamarripa-Dorsey F. Respuesta clínica en pacientes mexicanos con síndrome de intestino irritable tratados con dieta baja en carbohidratos fermentables (FODMAP). Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2015;80:180–185.

See related content at DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rgmx.2015.07.002, Schmulson M. Does a low FODMAP diet improve symptoms in Mexican patients with IBS? Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2015;80:177–179.