In Mexico 85% of midgut bleeding is secondary to angiodyplasia, ulcers, and benign and malignant tumors.1 Intestinal parasitic disease is an infrequent cause of midgut bleeding. Uncinariasis, or hookworm disease, is an intestinal parasitic infection produced by Necator americanus (N. americanus) and Ancylostoma duodenale, which are distributed throughout the world. However, N. americanus is commonly observed in the southern part of North America, in Central America, South America, Africa, and in tropical Asia.2 This report presents the first case of midgut bleeding caused by uncinariasis and diagnosed through capsule endoscopy (CE) in Mexico.

A 43-year-old woman from a semirural area at the border of Mexico and the United States (State of Tamaulipas) had a past medical history of mental retardation and paralysis of the extremities due to unknown causes. She was referred to our center due to intermittent hematochezia of 3-year progression. The patient stated she had no previous abdominal pain or chronic intake of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Apart from paleness of the skin and teguments, the physical examination was unremarkable. The laboratory work-up reported hemoglobin of 8 g/dL (normal: 13-16), MCV 72 fl (normal: 78-100), normal leukocytes, and eosinophilia of 18% (normal: 0-8).

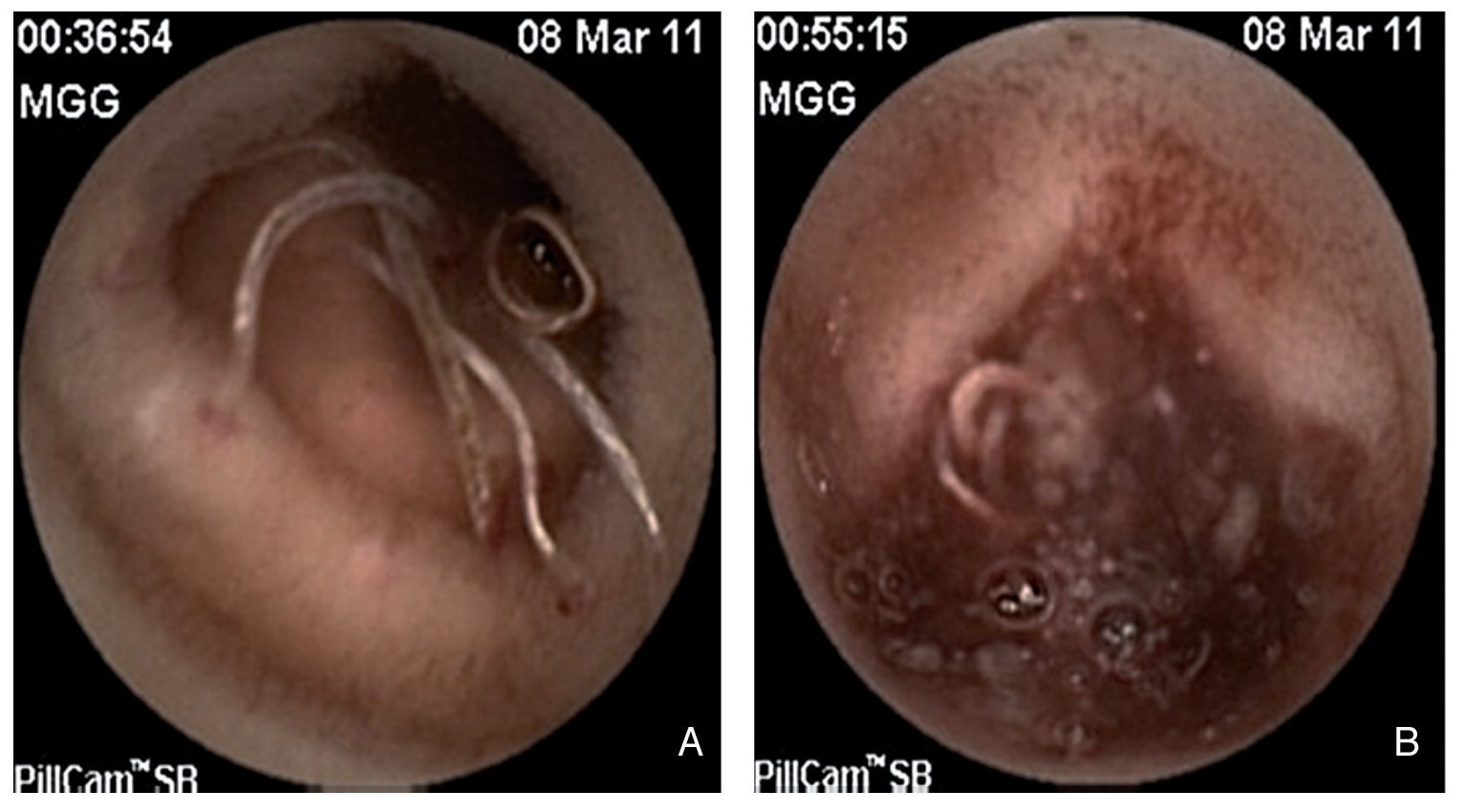

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed no vascular or mucosal lesions and ileocolonoscopy revealed ulcers in the terminal ileum. There was no histopathologic report. The patient was treated with oral mesalazine, the dose and length of time of which were not specified, and she had intermittent episodes of hematochezia (fresh, bright red blood and nonpainful) and persistent iron deficiency anemia on more than 3 occasions. One year later, control endoscopy (EGD and colonoscopy) and mesenteric angiography did not reveal the site of the bleeding. After intestinal segment resection due to a Meckel's diverticulum during exploratory laparotomy, the patient presented with new episodes of hematochezia and persistence of the anemia. She required blood transfusions during the last 2 years (40 U of packed red blood cells). Enteroscopy with CE (Pillcam SB, GIVEN Imaging Ltd, Yokneam, Israel) identified erythema, multiple erosions, and edema of the jejunal mucosa; abundant parasites with blood inside some of them were adhered to the intestinal mucosa and intestinal bleeding secondary to ulcers was observed (Figs. 1A and 1B). The patient was treated with an antiparasitic agent (albendazole) and iron supplements; 12 months later she was in good general condition, with no evidence of hematochezia or clinical or laboratory data of anemia. Hookworms specifically affect humans. The infective filariform larvae are present in moist soil. They penetrate the skin when they come into contact with an individual, producing a pruritic, erythematous, papular skin eruption. The larvae pass into the blood stream and from there to the pulmonary alveoli where, through bronchial secretions, they are absorbed into the digestive tract.3 Eosinophilia has been reported in 30 to 40% of the cases. Both types of hookworms parasitize in the proximal part of the small bowel in their adult forms, measuring approximately 10 to 15 mm in length. They firmly adhere to the intestinal mucosa by means of buccal cutting plates and suck blood while secreting anticoagulant enzymes to maintain the blood flow. The severity of the illness depends on the quantity of parasites.4 In this special case report, we present evidence of chronic midgut bleeding secondary to uncinariasis documented through clinical manifestations (intermittent hematochezia), laboratory results (persistent anemia and eosinophilia), and endoscopic capsule (bleeding jejunal ulcers). The patient had good treatment response in the follow-up visit 12 months after being managed with antiparasitic agents and iron supplements. Even though parasitic disease is an infrequent cause of midgut bleeding, it can be suspected in subjects with risk factors (mental retardation; living in rural areas) and with persistent eosinophilia, regardless of the geographic region. This case was a true diagnostic challenge. When midgut bleeding study protocol is not followed the diagnosis is more difficult, medical attention is more expensive, and the patient is at risk for morbidity resulting from decisions that are not well founded. Currently the consensus is to carry out enteroscopy through capsule endoscopy when midgut bleeding is suspected. A stool test can identify the eggs of the parasite. In our case they were not reported.

Figure 1 A) Various worms can be seen adhered to the jejunal mucosa, some of which have blood inside them. There is blood at the adherence sites. B) Active bleeding can be observed in the distal jejunum with a large quantity of worms in the intestinal lumen.

CE revealed the presence of the parasite in the small bowel and active bleeding ulcers. Even though there are recent reports of cases of midgut bleeding produced by intestinal uncinariasis diagnosed through CE from China, Greece, and the United States5-8 (Texas), this is the first case that has been reported in Mexico. In conclusion, this report of an isolated case described an infrequent cause of midgut bleeding that should be contemplated in the differential diagnosis in at-risk subjects. In this case there was strong evidence of bleeding ulcers secondary to uncinariasis that conditioned hematochezia and persistent anemia and eosinophilia.

Financial disclosure

No financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

* Corresponding author at:

Madero y Gonzalitos S/N, Monterrey NL. 64700 Mexico.

Tel./Fax: +(81) 8333-3664.

E-mail address: digarciacompean@prodigy.net.mx (D. Garcia-Compean).