Allgrove syndrome (AS) is a progressive, neuroendocrine disorder of unknown etiology, with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, that is characterized by achalasia, alacrima, adrenal insufficiency, and autonomic and neurologic alterations. It involves homozygous mutations in the AAAS gene that is located on chromosome12q13 and encodes the ALADIN protein (c.1331 + 1G > A is the most widely reported mutation worldwide), and the estimated prevalence is 1/1,000,000 persons1,2.

A 21-month-old female toddler had a full-term birth history. She was the second child born to healthy nonconsanguineous parents and had a healthy brother. Postnatal weight was 3.075 kg, postnatal length was 48 cm, and she had no perinatal hypoxia. Ever since birth, the patient did not produce tears. She presented with malnutrition (weight gain of 900 g in 18 months), with episodes of vomiting starting at 9 months of age (daily, abundant, and immediately postprandial, consisting of undigested food), and dysphagia to solids (ingesting 65 kcal/kg/day). She received prokinetics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and extensively hydrolyzed formula, with no improvement.

Physical examination revealed weight of 6.2 kg, length 74 cm, head circumference 43 cm, no characteristic facies, partial alopecia, no tears, generalized muscle weakness and atrophy, global developmental delay (GDD), and severe chronic malnutrition. No cutaneous hyperpigmentation was observed.

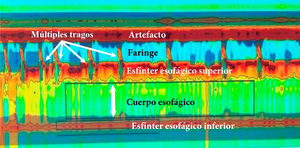

The patient was admitted to the hospital for nutritional recovery through enteral feeding, in accordance with the World Health Organization guidelines for in-hospital treatment of children with severe malnutrition. A contrast esophagram series showed a “bird’s beak” appearance (Fig. 1). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed dilation of the distal esophagus with food remnants. High-resolution esophageal manometry identified type I esophageal achalasia (EA) (Fig. 2). Schirmer’s test was positive and the levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol were normal.

High-resolution esophageal manometry. Type I achalasia. Note the coordination between the pharyngeal contraction and upper esophageal sphincter relaxation, with each swallow, as well as the absence of esophageal body peristalsis and LES relaxation. Mean IRP of 22 mmHg (normal <20), absence of esophageal body peristalsis in 100% of the swallows, absence of LES relaxation, mean LES pressure of 48 mmHg (normal 10–45); and mean DCI of 160 mmHg/cm/s (normal 450–8000).

DCI: distal contractile integral: IRP: integrated relaxation pressure; LES: lower esophageal sphincter.

The patient underwent laparoscopic Heller cardiomyotomy and partial anterior Dor fundoplication, with no complications, and 14 months later, presented with dysphagia to solids. Slight dilation of the distal esophagus was observed, and it was dilated to 10 mm with a through-the-scope pneumatic balloon, at the level of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

Currently, at the age of four years and 2 months, the patient has adequate esophageal distensibility, no stricture, and a functional surgical fundoplication. Her nutritional status has improved (mild chronic malnutrition) and her growth velocity was 6.5 cm/year. There is no corneal epithelial defect and no adrenal insufficiency. The patient is receiving physical and occupational therapy due to her GDD and is under treatment with prokinetics and a homemade blenderized diet because of regurgitation.

There are few reports of pediatric cases of this disease in Latin America, and to the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first report of AS in a Latin American toddler. In publications from Mexico, alacrima was reported as the primary symptom, followed by achalasia. Adrenal insufficiency was documented in one of 3 patients, at 5 years of age. Another patient presented with autonomic and peripheral neurologic dysfunction3–5.

Full-term neonates present with tears from the first day of extrauterine life and lacrimal fluid production is completely developed between 1 and 7 weeks of life. Alacrima is considered an early symptom of AS, and when present, the syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis6.

EA is a motility disorder with an estimated annual prevalence of 0.18/100,000 children. Symptoms are vomiting, dysphagia, and weight loss, and were documented in our patient as secondary to EA and leading to severe malnutrition. Chronic cough is described in 46.1% of cases of EA, which is often confused with gastroesophageal reflux disease, and up to half of patients receive prokinetics and PPIs before being diagnosed, as occurred in the present case7. The American College of Gastroenterology states that achalasia should be suspected in patients with dysphagia for liquids and solids, and in patients with regurgitation that do not respond to adequate-dose PPI therapy8. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) provides first-line imaging that aids in diagnosing EA but it can be negative in up to one-third of cases. It is useful for evaluating late changes that impact treatment. Endoscopic evaluation of the esophagogastric junction is recommended in all patients to rule out mechanical obstruction or pseudo-achalasia. Patients with no signs of obstruction should preferably undergo high-resolution esophageal manometry, which is the gold standard for making the diagnosis. Not only does it have improved diagnostic capacity, but also the capacity to guide treatment, according to the type of EA8. There are therapeutic approaches to EA that focus on reducing the LES pressure and facilitating gastric emptying. Some measures have a temporary effect and are designed for high-risk surgical patients that are not candidates for anesthesia, such as botulinum toxin application and/or oral administration of calcium channel blockers. Treatments with a prolonged effect include esophageal dilation and esophagomyotomy, with or without fundoplication9. The treatment of choice for EA is still controversial, heterogeneous, and involves a multidisciplinary team. Depending on the achalasia subtype, many pediatric gastroenterologists recommend laparoscopic Heller myotomy, while others suggest esophageal dilation10. In general, the recommendation is to discuss options with the family, taking into account the experience of the center where the patient is to be treated. There are few studies on pediatric patients that report a lasting effect, regarding intervention results.

The adrenal crisis is the first cause of mortality in AS. It occurs as episodes of hypoglycemia and progressive hyperpigmentation and is mostly limited to glucocorticoid deficiency11. Importantly, ACTH-resistant adrenal insufficiency is part of the classic triad of AS and is apparent at the end of the first decade of life. It can present 5–10 years after the initial onset of symptoms of EA, developing during late childhood, in adolescence, or even in adulthood12,13. Thus, continuous monitoring of serum electrolytes is suggested, especially during events of stress11.

Unfortunately, our case study was limited by the fact that no genetic studies were performed due to their high cost, which is an aspect reflected in everyday clinical practice. Genetically, AS is very heterogeneous. There are cases of diagnosed patients with no mutations in the AAAS gene, signifying that there could be other genes implicated in the disease2. Nevertheless, our patient has a confirmed diagnosis of achalasia, she is receiving adequate treatment despite her young age, and we believe our report will help others identify cases of AS, preventing delay in the diagnosis, especially in children under 2 years of age that present with nonspecific symptoms.

Because AS is a rare condition, there must be a high level of suspicion, emphasizing the importance of taking an adequate clinical history and knowing how to approach some of the most frequent symptoms seen in the pediatric population.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that the present article contains no information that could identify the patient. Given that a clinical case record was reviewed, authorization by an ethics committee was not required.

Financial disclosureNo specific grants were received from public sector agencies, the business sector, or non-profit organizations in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Alejandra Consuelo Sánchez of the Department of Gastroenterology and Nutrition at the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, Mexico City, Mexico.

Please cite this article as: Rivera-Suazo Y, Espriu-Ramírez MX, Trauernicht-Mendieta SA, Rodríguez L. Síndrome de Allgrove en lactante: alacrimia, acalasia, sin insuficiencia suprarrenal. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2021;86:441–443.