Boerhaave syndrome is the spontaneous rupture of the esophageal wall. It accounts for 8 to 56% of all esophageal perforations and is a potentially life-threatening syndrome.1

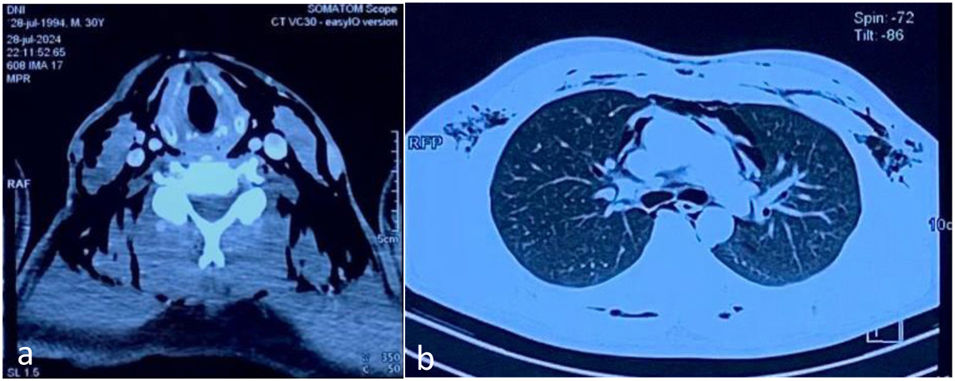

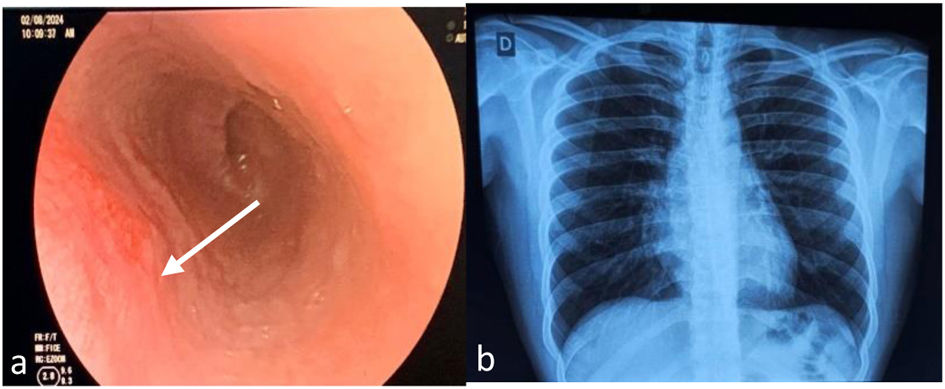

A 30-year-old man with no previously known comorbidities was admitted to the hospital due to 7 episodes of intense vomiting that had begun one hour earlier, after having eaten an abundant amount of food. The patient presented with intense epigastralgia and retrosternal pain (8/10), as well as dyspnea and odynophagia. Physical examination revealed he was conscious, complaining, polypneic, tachycardic and diaphoretic, with subcutaneous emphysema in the lateral regions of the neck and upper chest. No other alterations were observed. The laboratory work-up reported hemoglobin 16.6 g/dl, hematocrit 51%, leukocytes 26,800 × 103/μl, immature neutrophils 14%, glucose 234 mg/dl, and C-reactive protein 60 mg/l. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck identified extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the base and lateral regions of the neck (Fig. 1a) and a contrast-enhanced chest CT scan showed pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium (Fig. 1b). Boerhaave syndrome was suspected, and the patient was kept in a fasting state. Endovenous analgesia and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy were started. On day 7 of hospitalization, the patient showed clinical and laboratory parameter improvement. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed that revealed an area of linear erythema in the left wall of the mid-to-distal esophagus (Fig. 2a) and a chest x-ray showed no alterations (Fig. 2b). Oral diet was restarted, the patient’s progression was favorable, and he was discharged.

Boerhaave syndrome is the spontaneous rupture of the esophageal wall secondary to retching, vomiting, or any vigorous straining that increases the intraluminal pressure.2 It affects 3.1 per 1,000,000 patients annually, with morbidity and mortality rates of up to 50%.2,3 Clinically, 14% of patients seek medical attention due to chest pain, vomiting, and subcutaneous emphysema (the Mackler triad), but symptoms can be nonspecific, making the diagnosis a challenge.4,5 Contrast-enhanced CT has high diagnostic sensitivity (92-100%), detecting mediastinal involvement, through the presence of air or secondary abscesses.6 After diagnosis, treatment should be early, significantly decreasing mortality (below 10%).3,6 Some patients may be candidates for conservative treatment, as long as they are hemodynamically stable, the esophageal rupture is contained, and mediastinal contamination is limited.7 Said treatment encompasses null oral intake, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the start of proton pump inhibitor therapy.6,8 If the patient requires an intervention, endoscopy is a less invasive option that enables the placement of clips and covered metallic stents, as well as endoluminal vacuum therapy. However, surgery is indicated as the first therapeutic option, in patients with large perforations, septic shock, or an associated esophageal disease.8,9

In conclusion, Boerhaave syndrome is a rare esophageal disease, with a great risk of complications and death. Timely suspicion and diagnosis, together with individualized treatment, improve the prognosis.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that no experiments were conducted on humans for this research. We employed the patient data collection protocols of our work center pertaining to databases. No personal data were published in this article that could identify the patient, and so informed consent was not required. This study meets the current bioethical research regulations. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital La Caleta de Chimbote authorized this study, given the information described above.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.