Clostridium difficile is the first cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea in developed countries. In recent years the incidence of C. difficile infection (CDI) has increased worldwide. There is not much information on the topic in Mexico, and little is known about the risk factors for the infection in patients that are hospitalized in surgical services.

Materials and methodsA case-control study was conducted that compared the epidemiologic findings and risk factors between surgical patients with PCR-confirmed CDI, surgical patients with diarrhea and a negative PCR test, and surgical patients with no diarrhea. The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS version 22.0 program.

ResultsThe majority of the surgical patients with CDI belonged to the areas of neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, orthopedics, and general surgery. A total of 53% of the CDI cases were associated with the hypervirulent CD NAP1/027 strain. The presence of mucus in stools (OR: 1.5, p = 0.001), fever (OR: 1.4, p = 0.011), leukocytes in stools (OR: 3.2, p < 0.001), hospitalization within the past twelve weeks (OR: 2.0, p < 0.001), antibiotic use (OR: 1.3, p = 0.023), and ceftriaxone use (OR: 1.4, p = 0.01) were independent risk factors for the development of CDI.

ConclusionsC. difficile-induced diarrhea in the surgical services is frequent at the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde”.

Clostridium difficile (CD) es la primera causa de diarrea asociada al cuidado de salud en los países desarrollados. En los últimos años, la incidencia de la infección asociada a C. difficile (ICD) ha aumentado en el ámbito mundial. En México, la información al respecto es escasa, y se conoce poco sobre los factores de riesgo para esta enfermedad en pacientes hospitalizados en servicios quirúrgicos.

Material y métodosEstudio de casos y controles. Se compararon hallazgos epidemiológicos y factores de riesgo entre pacientes quirúrgicos con ICD confirmada por PCR contra pacientes quirúrgicos con diarrea PCR negativa y contra pacientes quirúrgicos sin diarrea. Se realizó análisis estadístico mediante el paquete estadístico SPSS versión 22.0.

ResultadosLa mayoría de los pacientes quirúrgicos con ICD correspondían a las áreas de neurocirugía, cardiocirugía, ortopedia y cirugía general. El 53% de los casos de ICD se asociaron a la cepa hipervirulenta de CD NAP1/027. La presencia de moco en heces (RM 1.5, p = 0.001), fiebre (RM 1.4, p = 0.011), leucocitos en heces (RM 3.2, p=<0.001), hospitalización en las últimas doce semanas (RM 2.0, p=<0.001), uso de antibióticos (RM 1.3, p = 0.023) y uso de ceftriaxona (RM 1.4, p = 0.01) constituyeron factores de riesgo independientes para el desarrollo de ICD.

ConclusionesLa diarrea por CD en servicios quirúrgicos es frecuente en nuestra institución (Hospital Civil de Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde”).

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is the main cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea and is the most frequent cause in certain countries.1

In a 1986 case-control study, the authors reported that 87% of CDIs were hospital-acquired, and 75% of them were in patients in the surgical services. The risk factors included having a previous infection, multiple antibiotic use, especially clindamycin, prior to the appearance of CDI, and prolonged hospitalization.2 Olson et al. reported that approximately half of the patients with CDI belonged to a surgical service.3

In recent years, different researchers on surgery described the presence of CDI in surgical patients after colorectal resection (2.2%), with important variations between different surgeons and hospitals,4 reporting an incidence of 1.8% after ileostomy.5

The burden of CDI in surgery has been reported in different countries: 21,371 general surgery patients (0.47%) in the United Kingdom; 19 out of 4,720 patients (0.4%) in Korea; 143,652 surgical procedures (0.28%) in Japan; and 2,581 out of 349,122 patients (0.75%) in the United States, as well as 35,363 patients (0.51%) after 40 types of surgery in 52 hospitals.6–10

The real burden of CDI in hospital surgical areas is not specifically described in the majority of reports published on C. difficile, but that does not mean those patients were not affected by the pathology.

In the relation between prophylactic antibiotic administration in surgical patients to its association as a risk factor for developing CDI, there is also an increased risk for infection due to the hypervirulent C. difficile NAP1/027 strain.11,12

AimThe aim of the present study was to analyze the risk factors for acquiring CDI in patients hospitalized in the surgical services at the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde.

Materials and methodsStudy siteThe present study was conducted at the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde, a tertiary care university hospital with 890 long-stay hospital beds, located in Guadalajara, Jalisco.

Study designThe case-control study was carried out within the time frame of December 2013 to September 2016. A prospective follow-up was conducted on all cases of diarrhea found at our hospital. The study focused on patients in the surgical wards, identifying the study subjects as surgical cases with diarrhea and a positive PCR test for C. difficile (Cepheid Xpert C. difficile/Epi Cepheid, Sunnyvale CA), surgical cases with diarrhea and a negative PCR test (controls-1), and surgical cases with no diarrhea that were in the same wards for the same period of time (controls-2). Demographic, epidemiologic, and clinical data were obtained. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara. All patients signed statements of informed consent that were authorized by the Ethics Committee.

DefinitionsHealthcare-associated diarrhea was defined by the presence of stools with a consistency matching the Bristol scale type 5 to 7, with 3 or more bowel movements in 24 h, after 48 h of hospital admission (Mexican Official Norm NOM-017-SSA2-2012, for epidemiologic surveillance). CDI was defined as healthcare-associated diarrhea with a positive PCR analysis for C. difficile.

Statistical analysisSpecific univariate descriptive statistics for the surgical services were carried out, including the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of the study population. The dichotomous variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and the quantitative variables as medians and ranges. The bivariate comparison analysis between groups was performed using the chi-square test for the qualitative variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for the quantitative variables. The risk factors were determined by submitting the variables with a probability of 0.20 or lower, which were then adjusted to a linear regression model. The SPSS version 22.0 was utilized to carry out the statistical analysis and statistical significance was set at a p < 0.05.

Ethical considerationsThe present study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara. All patients signed statements of informed consent and patient data remained confidential and anonymous, following the protocols of our work center.

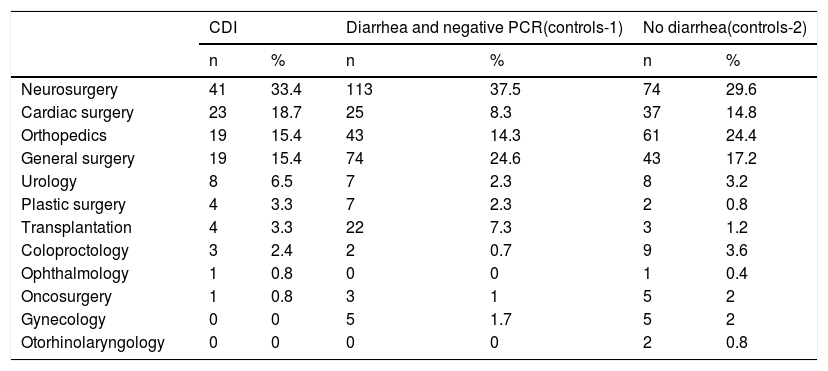

ResultsThe majority of the 123 surgical cases with CDI were in the services of neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, orthopedics, and general surgery. Eighty-five percent of all the surgical cases in those services were registered with diarrhea and negative PCR testing, and 86% were registered with no diarrhea (Table 1).

Surgical service distribution of the cases and controls.

| CDI | Diarrhea and negative PCR(controls-1) | No diarrhea(controls-2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Neurosurgery | 41 | 33.4 | 113 | 37.5 | 74 | 29.6 |

| Cardiac surgery | 23 | 18.7 | 25 | 8.3 | 37 | 14.8 |

| Orthopedics | 19 | 15.4 | 43 | 14.3 | 61 | 24.4 |

| General surgery | 19 | 15.4 | 74 | 24.6 | 43 | 17.2 |

| Urology | 8 | 6.5 | 7 | 2.3 | 8 | 3.2 |

| Plastic surgery | 4 | 3.3 | 7 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.8 |

| Transplantation | 4 | 3.3 | 22 | 7.3 | 3 | 1.2 |

| Coloproctology | 3 | 2.4 | 2 | 0.7 | 9 | 3.6 |

| Ophthalmology | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Oncosurgery | 1 | 0.8 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Gynecology | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1.7 | 5 | 2 |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.8 |

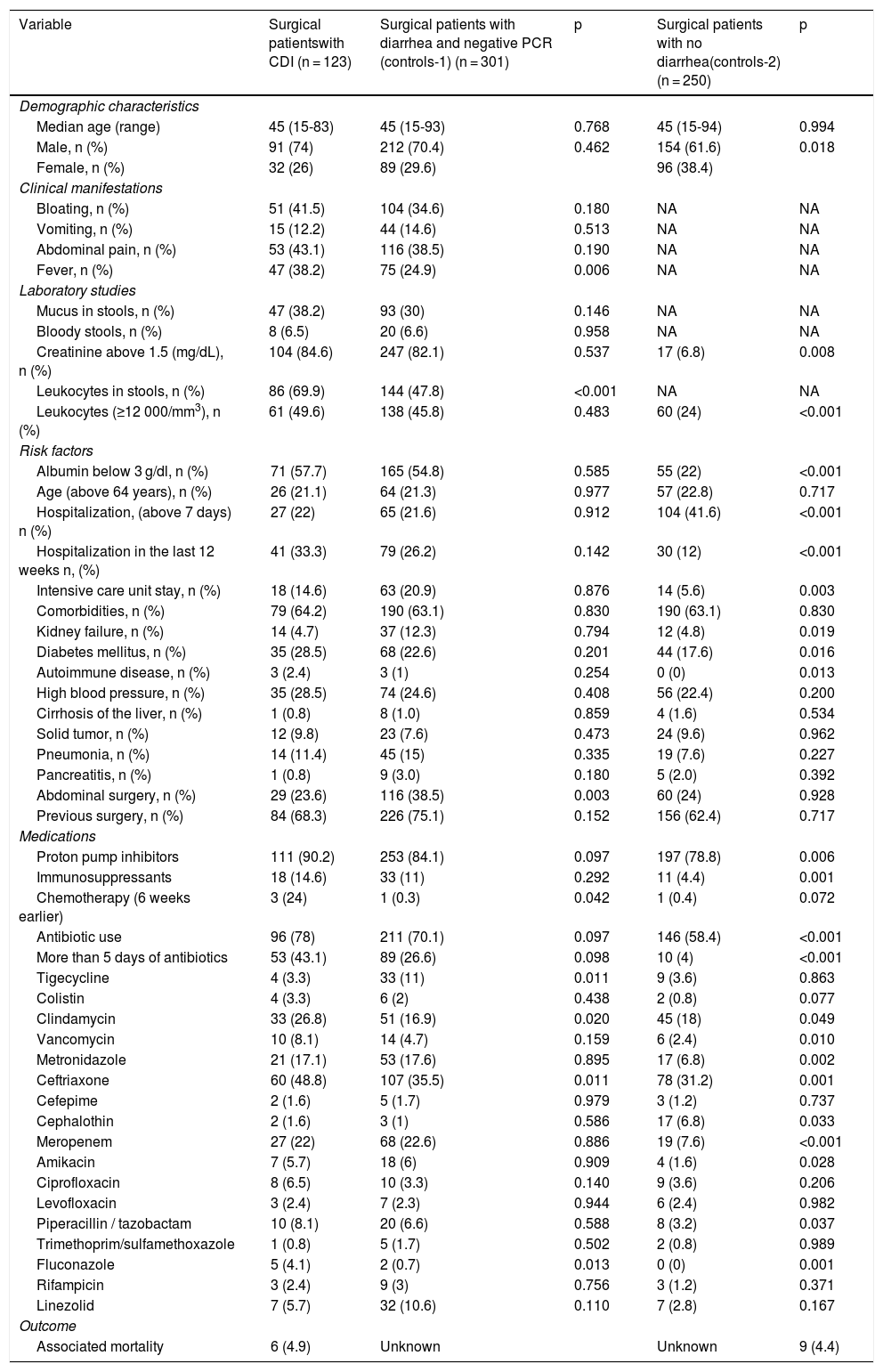

A total of 123 surgical cases with CDI were detected, along with 301 surgical cases with diarrhea and a negative PCR analysis, and 255 surgical cases with no diarrhea (Table 2). The presence of leukocytes (≥12,000 cell/mm3), albumin (under 3 g/dl), hospitalization (more than 7 days), hospitalization within the last 12 weeks, immunosuppressant use, antibiotic use, and meropenem and fluconazole use were more frequent in surgical patients with CDI than in surgical patients with no diarrhea (p < 0.001). In addition, the presence of leukocytes in stools was more frequent in surgical patients with CDI than in surgical patients with diarrhea and a negative PCR test (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cases and controls.

| Variable | Surgical patientswith CDI (n = 123) | Surgical patients with diarrhea and negative PCR (controls-1) (n = 301) | p | Surgical patients with no diarrhea(controls-2) (n = 250) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Median age (range) | 45 (15-83) | 45 (15-93) | 0.768 | 45 (15-94) | 0.994 | |

| Male, n (%) | 91 (74) | 212 (70.4) | 0.462 | 154 (61.6) | 0.018 | |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (26) | 89 (29.6) | 96 (38.4) | |||

| Clinical manifestations | ||||||

| Bloating, n (%) | 51 (41.5) | 104 (34.6) | 0.180 | NA | NA | |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 15 (12.2) | 44 (14.6) | 0.513 | NA | NA | |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 53 (43.1) | 116 (38.5) | 0.190 | NA | NA | |

| Fever, n (%) | 47 (38.2) | 75 (24.9) | 0.006 | NA | NA | |

| Laboratory studies | ||||||

| Mucus in stools, n (%) | 47 (38.2) | 93 (30) | 0.146 | NA | NA | |

| Bloody stools, n (%) | 8 (6.5) | 20 (6.6) | 0.958 | NA | NA | |

| Creatinine above 1.5 (mg/dL), n (%) | 104 (84.6) | 247 (82.1) | 0.537 | 17 (6.8) | 0.008 | |

| Leukocytes in stools, n (%) | 86 (69.9) | 144 (47.8) | <0.001 | NA | NA | |

| Leukocytes (≥12 000/mm3), n (%) | 61 (49.6) | 138 (45.8) | 0.483 | 60 (24) | <0.001 | |

| Risk factors | ||||||

| Albumin below 3 g/dl, n (%) | 71 (57.7) | 165 (54.8) | 0.585 | 55 (22) | <0.001 | |

| Age (above 64 years), n (%) | 26 (21.1) | 64 (21.3) | 0.977 | 57 (22.8) | 0.717 | |

| Hospitalization, (above 7 days) n (%) | 27 (22) | 65 (21.6) | 0.912 | 104 (41.6) | <0.001 | |

| Hospitalization in the last 12 weeks n, (%) | 41 (33.3) | 79 (26.2) | 0.142 | 30 (12) | <0.001 | |

| Intensive care unit stay, n (%) | 18 (14.6) | 63 (20.9) | 0.876 | 14 (5.6) | 0.003 | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 79 (64.2) | 190 (63.1) | 0.830 | 190 (63.1) | 0.830 | |

| Kidney failure, n (%) | 14 (4.7) | 37 (12.3) | 0.794 | 12 (4.8) | 0.019 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 35 (28.5) | 68 (22.6) | 0.201 | 44 (17.6) | 0.016 | |

| Autoimmune disease, n (%) | 3 (2.4) | 3 (1) | 0.254 | 0 (0) | 0.013 | |

| High blood pressure, n (%) | 35 (28.5) | 74 (24.6) | 0.408 | 56 (22.4) | 0.200 | |

| Cirrhosis of the liver, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 8 (1.0) | 0.859 | 4 (1.6) | 0.534 | |

| Solid tumor, n (%) | 12 (9.8) | 23 (7.6) | 0.473 | 24 (9.6) | 0.962 | |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 14 (11.4) | 45 (15) | 0.335 | 19 (7.6) | 0.227 | |

| Pancreatitis, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 9 (3.0) | 0.180 | 5 (2.0) | 0.392 | |

| Abdominal surgery, n (%) | 29 (23.6) | 116 (38.5) | 0.003 | 60 (24) | 0.928 | |

| Previous surgery, n (%) | 84 (68.3) | 226 (75.1) | 0.152 | 156 (62.4) | 0.717 | |

| Medications | ||||||

| Proton pump inhibitors | 111 (90.2) | 253 (84.1) | 0.097 | 197 (78.8) | 0.006 | |

| Immunosuppressants | 18 (14.6) | 33 (11) | 0.292 | 11 (4.4) | 0.001 | |

| Chemotherapy (6 weeks earlier) | 3 (24) | 1 (0.3) | 0.042 | 1 (0.4) | 0.072 | |

| Antibiotic use | 96 (78) | 211 (70.1) | 0.097 | 146 (58.4) | <0.001 | |

| More than 5 days of antibiotics | 53 (43.1) | 89 (26.6) | 0.098 | 10 (4) | <0.001 | |

| Tigecycline | 4 (3.3) | 33 (11) | 0.011 | 9 (3.6) | 0.863 | |

| Colistin | 4 (3.3) | 6 (2) | 0.438 | 2 (0.8) | 0.077 | |

| Clindamycin | 33 (26.8) | 51 (16.9) | 0.020 | 45 (18) | 0.049 | |

| Vancomycin | 10 (8.1) | 14 (4.7) | 0.159 | 6 (2.4) | 0.010 | |

| Metronidazole | 21 (17.1) | 53 (17.6) | 0.895 | 17 (6.8) | 0.002 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 60 (48.8) | 107 (35.5) | 0.011 | 78 (31.2) | 0.001 | |

| Cefepime | 2 (1.6) | 5 (1.7) | 0.979 | 3 (1.2) | 0.737 | |

| Cephalothin | 2 (1.6) | 3 (1) | 0.586 | 17 (6.8) | 0.033 | |

| Meropenem | 27 (22) | 68 (22.6) | 0.886 | 19 (7.6) | <0.001 | |

| Amikacin | 7 (5.7) | 18 (6) | 0.909 | 4 (1.6) | 0.028 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8 (6.5) | 10 (3.3) | 0.140 | 9 (3.6) | 0.206 | |

| Levofloxacin | 3 (2.4) | 7 (2.3) | 0.944 | 6 (2.4) | 0.982 | |

| Piperacillin / tazobactam | 10 (8.1) | 20 (6.6) | 0.588 | 8 (3.2) | 0.037 | |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 1 (0.8) | 5 (1.7) | 0.502 | 2 (0.8) | 0.989 | |

| Fluconazole | 5 (4.1) | 2 (0.7) | 0.013 | 0 (0) | 0.001 | |

| Rifampicin | 3 (2.4) | 9 (3) | 0.756 | 3 (1.2) | 0.371 | |

| Linezolid | 7 (5.7) | 32 (10.6) | 0.110 | 7 (2.8) | 0.167 | |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Associated mortality | 6 (4.9) | Unknown | Unknown | 9 (4.4) | ||

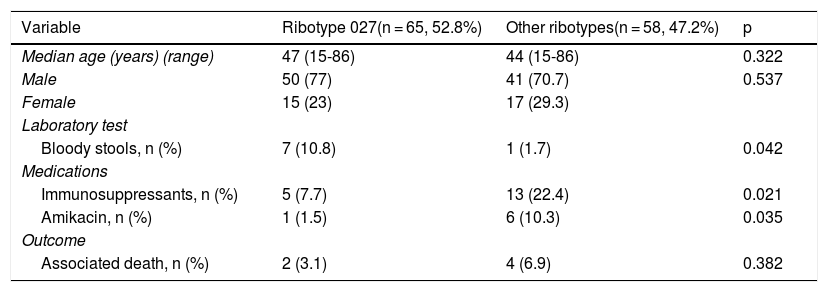

Surgical patients with CDI with the C. difficile NAP1/027 strain had higher levels of bloody stools (p = 0.042) and greater use of immunosuppressants (p = 0.021) and amikacin (p = 0.035) than the surgical patients infected with other C. difficile ribotypes (Table 3).

Variables of importance in the distribution of surgical cases with CDI according to ribotype.

| Variable | Ribotype 027(n = 65, 52.8%) | Other ribotypes(n = 58, 47.2%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) (range) | 47 (15-86) | 44 (15-86) | 0.322 |

| Male | 50 (77) | 41 (70.7) | 0.537 |

| Female | 15 (23) | 17 (29.3) | |

| Laboratory test | |||

| Bloody stools, n (%) | 7 (10.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0.042 |

| Medications | |||

| Immunosuppressants, n (%) | 5 (7.7) | 13 (22.4) | 0.021 |

| Amikacin, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 6 (10.3) | 0.035 |

| Outcome | |||

| Associated death, n (%) | 2 (3.1) | 4 (6.9) | 0.382 |

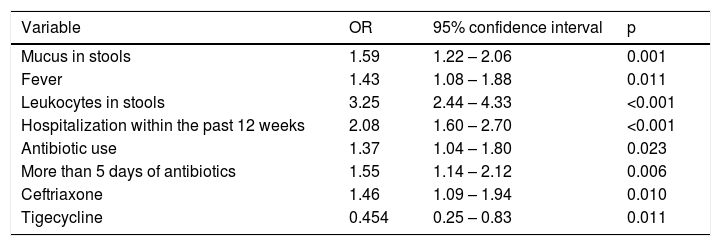

In the multivariate analysis, the presence of mucus in stools (p = 0.001), fever (p = 0.011), leukocytes in stools (p < 0.001), hospitalization within the past 12 weeks (p < 0.001), antibiotic use (p = 0.023), and ceftriaxone use (p = 0.01) were independent risk factors for developing CDI. Tigecycline use was greater in the surgical controls with diarrhea and a negative PCR analysis (p = 0.011) (Table 4).

Logistic regression analysis of the significant variables and p value below 0.02.

| Variable | OR | 95% confidence interval | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mucus in stools | 1.59 | 1.22 – 2.06 | 0.001 |

| Fever | 1.43 | 1.08 – 1.88 | 0.011 |

| Leukocytes in stools | 3.25 | 2.44 – 4.33 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization within the past 12 weeks | 2.08 | 1.60 – 2.70 | <0.001 |

| Antibiotic use | 1.37 | 1.04 – 1.80 | 0.023 |

| More than 5 days of antibiotics | 1.55 | 1.14 – 2.12 | 0.006 |

| Ceftriaxone | 1.46 | 1.09 – 1.94 | 0.010 |

| Tigecycline | 0.454 | 0.25 – 0.83 | 0.011 |

CDI is mainly associated with healthcare services that affect the adult population in both the medical and surgical services. The authors of a recent study stated that 36% of CDI cases in 2015 were patients with a history of surgery, 7% of which were abdominal surgeries.13

In our study, the patients hospitalized in the surgical services, especially in neurosurgery, were documented as having a high risk for developing CDI, as reported in the literature.

Surgical patients are susceptible to exposure to the risk factors described for the development of CDI in the adult patient, which are prophylactic antibiotics, older age, a higher number of immunosuppressed patients requiring transplantation, orthopedic procedures for prosthesis placement, and intestinal surgery.2,14–18 The 027 strain is linked to different results in patients with CDI. According to the results of a Canadian multicenter study that included 12 hospitals, the authors found that the percentage of affected patients coming from surgical services was below 32.9%, compared with the 56.1% from the medical service wards. It should be mentioned that, for their study, the C. difficile 027 strain was already circulating.15

For example, in a study that included 134 hospitals and 468,386 procedures, in which CDI was looked for after a surgery, a CDI rate of 0.4 per year was found, with differences between hospitals (rates from 0.04 to 1.4%) and between surgical specialties (from 0.0 to 2.4%). The risk factors in that study population were: advanced age, hospitalization after surgery, and treatment with > 3 antibiotics.16

Knowledge of the particular risk factors for the surgical patient is crucial for early diagnosis, adequate treatment, and prevention.

The problem of the association between the patient undergoing neurosurgery and CDI was recently reviewed. Those patients are often admitted to the intensive care unit for close surveillance due to the diversity of complications that can present and are exposed to the risk of developing healthcare-associated infections. A total of 1.9% of patients have been reported to develop CDI after subarachnoid hemorrhage.19

As in our study, patients in cardiac surgery services are affected by CDI. They frequently present with concomitant diseases, receive antibiotics for long periods of time, are admitted to a specialized intensive care unit, and undergo procedures with multiple instrumentation. Incidence of CDI development in patients in cardiac surgery has been reported at 0.75%.9

Surgical patients in the orthopedics service are at risk for acquiring CDI due to underlying disease and prolonged preoperative hospital stay. In our study, those patients were documented as susceptible to developing CDI. An increase in CDI and prophylactic strategies employing amoxicillin combined with clavulanic acid in orthopedic services was an effective decision for reducing the mortality rate by 80% in cases of CDI.20

Despite the fact that CDI is an emergent infection, according to the U. S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), little is known of its epidemiology in the surgical services in Mexico. In previous studies on Mexican patients with CDI-induced diarrhea, the problem was not specifically examined in surgical patients.21–25

Compared with reports in the medical literature, our surgical patients with CDI had a higher frequency of leukocytes in stools than the surgical patients with negative PCR (69.9 versus 47.8%). The search for leukocytes in stools is not recommended, given that it has 30% sensitivity, 74.9% specificity, 13.2% positive predictive value, and 89.3% negative predictive value, compared with the enzyme immunoassay for toxin A or B, signifying that a patient with CDI can mistakenly go untreated if the fecal leukocyte test is negative.26

Antibiotic use was shown to be a risk factor for acquiring CDI (p = 0.023) in our study, and the risk was greater if the antibiotic was administered for more than 5 days (p = 0.006). In addition, ceftriaxone was found to be a risk factor for developing CDI in the surgical services (OR: 1.46, p = 0.010). Those findings have been well-studied and there are programs on adequate antibiotic use in surgical services to control CDI. Not using preoperative prophylaxis with antimicrobials, eliminating the use of antibiotics that are high-risk for CDI, and using low-risk antibiotics, such as amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, has been proposed.12,20,27,28

A common finding has been the use of proton pump inhibitors, which in our study were administered in 90.2% of the surgical cases of CDI versus 78.8% of the controls-2 (p = 0.006), suggesting that the use of H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors should be reduced.6,8,29,30

The above-stated results on risk factors could be considered comparable to those from a study on a Mexican population with CDI by Pérez-Topete et al. They reported the previous use of antibiotics (83%) and the use of PPIs (54%), as the main risk factors for CDI. The most commonly used antibiotic in their study was ciprofloxacin. However, they did not discriminate between community-acquired CDI and hospital-acquired infection and the sample size was small (n = 55).31

Education, especially about the risk factors for CDI, is important for controlling said nosocomial infection. Implementing programs for adequate antimicrobial use (Antimicrobial Stewardship) in surgical services to control CDI is frequently discussed.32 In addition, there are numerous guidelines that provide recommendations for the prevention and control of CDI. In 2007, in the United Kingdom, the “High Impact Intervention No. 7” care bundle came out and its measures, such as rational antimicrobial use and contact precautions as basic strategies, were later reiterated in European and U.S. guidelines.33

The participation of surgical services is indispensable for implementing strategies to combat CDI, such as early surgical management, adequate application of antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery, and consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of CDI in their communities.34–38 Several Mexican authors have commented on the above in in an attempt to raise awareness, and different articles have stressed the obligation physicians have to increase their knowledge of CDI and practice strict surveillance of the high-risk population. In other words, it is time for us to be concerned about C. difficilein Mexico.39

Among the limitations of the present study was the lack of cultures for C. difficile, the limited use of colonic imaging, colonoscopy, and autopsies. Another limitation was not knowing the etiology of hospital-acquired diarrhea that was negative for C. difficile and that could have been secondary to other conditions, such as osmotic diarrhea (caused by tube feeding) or drug-induced diarrhea.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, patients hospitalized in the surgical services of our hospital, especially in neurosurgery, presented with a high risk for developing CDI. The present study confirmed previous antibiotic use, antibiotic use longer than 5 days, ceftriaxone use, and prior hospitalization as risk factors for acquiring CDI.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Morfín-Otero R, Petersen-Morfín S, Aguirre-Díaz SA, Pérez-Gómez HR, Garza-González E, González-Díaz E, et al. Diarrea asociada a Clostridioides difficile en pacientes de servicios quirúrgicos en México. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2020;85:227–234.