The adenoma detection rate (ADR) is the most important quality indicator for the prevention of colorectal cancer but serrated polyps are also precursor lesions of the disease. The aim of our study was to compare the detection rate of proximal serrated polyps (PSPs) and that of clinically significant serrated polyps (CSSPs) between endoscopists and analyze the relation of those parameters to the ADR.

MethodsAn observational, prospective, cross-sectional study was conducted on all patients that underwent colonoscopy at the Policlínico Peruano Japonés within the time frame of July 2015 and August 2016. The ADR and PSP and CSSP detection rates between endoscopists were compared through multivariate logistic regression and the association between those parameters was calculated through the Pearson correlation coefficient.

ResultsThe study included 15 endoscopists and 1,378 colonoscopies. The PSP detection rate ranged from 1.8-17% between endoscopists and had an almost perfect correlation with the CSSP detection rate (p = 0.922), as well as strongly correlating with the ADR (p = 0.769).

ConclusionsThere was great variability in the PSP detection rate between endoscopists. It also had an almost perfect correlation with the CSSP detection rate and strongly correlated with the ADR. Those results suggest a high CSSP miss rate at endoscopy and a low PSP detection rate.

La tasa de detección de adenomas (TDA) es el más importante indicador de calidad para la prevención del cáncer colorrectal. Sin embargo, los pólipos serratos también son lesiones precursoras de cáncer colorrectal. El objetivo del estudio fue comparar la tasa de detección de pólipos serratos proximales (PSP) y la tasa de detección de pólipos serratos clínicamente significativos (PSCS) entre endoscopistas, y analizar la relación entre estos parámetros y la TDA.

MétodosEstudio observacional, transversal y prospectivo. Se incluyeron a todos los pacientes que acudieron para colonoscopia al Policlínico Peruano Japonés entre julio del 2015 y agosto del 2016. Se utilizó regresión logística multivariada para comparar la TDA, la tasa detección de PSP y la tasa de detección de PSCS entre los endoscopistas. Se calculó la asociación entre estos parámetros mediante el coeficiente de correlación de Pearson.

ResultadosFueron incluidos 15 endoscopistas y 1378 colonoscopias. La tasa de detección de PSP estuvo en el rango de 1,8-17% entre los endoscopistas. La tasa de detección de PSP tuvo una correlación casi perfecta con la tasa de detección de PSCS (ρ = 0,922). La tasa de detección de PSP tuvo una fuerte correlación con la TDA (ρ = 0,769).

ConclusionesLa tasa de detección de PSP tiene gran variabilidad entre endoscopistas, y tiene una correlación casi perfecta con la tasa de detección de PSCS, y una fuerte correlación con la TDA. Estos resultados sugieren una alta tasa de PSCS perdidos por los endoscopistas con una baja tasa de detección de PSP.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most frequent causes of death from cancer worldwide1. It develops over time from precursor lesions. In fact, resecting those lesions reduces the incidence and mortality of CRC2,3. However, colonoscopy is not completely protective against the appearance of CRC, especially disease on the right side of the colon4,5. The majority of the so-called interval cancers develop from precancerous lesions that went undetected during a previous colonoscopy and most of them occur in the proximal colon6–9. In a systematic review and meta-analysis on the location of interval CRC (from six to 36 months after colonoscopy), the prevalence of proximal interval colon cancer was 6.5%, compared with 2.9% for distal interval colon cancer10. Two articles showed an inverse relation between the risk of interval cancer and the adenoma detection rate (ADR) of an endoscopist11,12. Thus, the ADR is considered the main quality indicator in the context of CRC prevention. Nevertheless, ADR is an inaccurate marker, given that the detection of just one adenoma is sufficient for considering a colonoscopy to be high quality (the one-and-done phenomenon, now described in the literature)13. We also know that adenomas are not the only precursor lesions of CRC14, and so other quality indicators need to be evaluated to consider a colonoscopy high quality.

For many years, adenomas have been considered the only premalignant lesion of CRC, but research in recent years has shown that serrated polyps also play an important role in CRC oncogenesis, being responsible for approximately 15-30% of all CRCs15. A significant number of all interval cancers develop from serrated polyps, presumably due to the high rate of undetected serrated polyps located in the proximal colon16. Serrated polyps may not be detected due to their indistinguishable edges, their flat aspect, and because they are often covered with a layer of mucus. However, not all serrated polyps appear to be premalignant. Diminutive hyperplastic polyps located in the rectum and sigmoid colon are considered benign, whereas large hyperplastic polyps and/or those located proximally, polyps/sessile serrated adenomas, and traditional serrated adenomas are considered to have a high neoplastic potential.14 We shall call those potentially malignant polyps “clinically significant serrated polyps” (CSSPs) and they should be detected and resected in a quality colonoscopy. Serrated polyp detection is not currently an established indicator of quality in colonoscopy.

Several studies have evaluated the variability of the detection rate of ≥1 proximal serrated polyp (PSP) between endoscopists17–21. The PSP detection rate is an easy parameter to measure that can be correlated with the CSSP detection rate. In a large retrospective study, the PSP detection rate was shown to be endoscopist-dependent, at a range of 1 to 18%, between 15 endoscopists17, and one prospective study described great variability (6-22%) between five endoscopists in the PSP detection rate18. In another prospective study conducted in Amsterdam, with 16 endoscopists and 2,088 colonoscopies, the PSP detection rate ranged from 2.9 to 18.6%19. The PSP detection rate in a French retrospective study, with 18 endoscopists and 2,979 complete colonoscopies, ranged from 1.28 to 19.25%20. More recently, in a study conducted in Washington on patients that underwent screening colonoscopy, there was a significant variation in PSP detection rates, ranging from 1.1 to 22%21.

The aim of the present study was to compare the PSP and CSSP detection rates between endoscopists and analyze the association between those two parameters and the ADR.

Materials and methodsAn analytic, observational, prospective cross-sectional study was conducted on outpatients that arrived at the gastroenterology service of the Policlínico Peruano Japonés for a colonoscopy, within the time frame of July 2015 and August 2016. The Policlínico Peruano Japonés is a private institution that treats outpatients. A total of 17 gastroenterologists performed the procedures, but only the interventions carried out by 15 of them were included in the analysis. The reason the two gastroenterologists were excluded was because they performed fewer than 30 colonoscopies during the study period. All the participating gastroenterologists were endoscopists with more than 10 years of experience and performed more than 100 colonoscopies per year at their different work centers. The colonoscopies were carried out utilizing the following equipment: Olympus®, models CF-H 180 and CF-Q 160ZL; Fujinon®, model EC-590 WL, and Pentax®, model EC-I10L. All the procedures were recorded and archived. All the patients received verbal and written instructions for bowel preparation, employing the divided dose system for all the procedures. The laxatives used for bowel preparation were PEG and sodium phosphate. If the colonoscopy was in the morning, the patient was instructed to take three packets of PEG the night before the study and one in the morning, or one bottle of sodium phosphate the night before and another in the morning. If the colonoscopy was in the afternoon, the indication was two packets of PEG the night before and two in the morning, the day of the exam, or one bottle of sodium phosphate the night before and another the morning of the exam.

During the procedure, the following colonoscopy data were collected: the endoscopist that performed the study, the time at which the study began, insertion depth, bowel preparation quality, and polyp characteristics. The bowel preparation was evaluated during the colonoscopy by the endoscopist using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS)22,23. Said scale has a scoring system from 0 to 3 points for each of the three segments of the colon: right colon (including the cecum and ascending colon), transverse colon (including the splenic and hepatic flexures), and left colon (including the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum). Scores range from 0 to 9, with lower scores corresponding to less-than-optimal preparations. Bowel preparation quality was categorized as excellent (BBPS score of 8 and 9), good (BBPS score of 6 and 7), and regular/poor (BBPS ≤ 5). The detected polyps were photographed, and their endoscopic characteristics described in the colonoscopy report, including their size and anatomic location. Each polyp was biopsied or resected and referred for histopathologic study. Polyp histopathology was evaluated, according to the revised Vienna criteria24, by three expert gastrointestinal pathologists. The polyps were subdivided into adenomatous polyps or serrated polyps. The serrated polyps were classified as hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated polyps, and traditional serrated adenomas, using World Health Organization criteria25. The proximal portion of the descending colon was defined as the proximal colon (splenic flexure, transverse colon, ascending colon, and cecum). All the detected serrated polyps in the proximal colon were included to measure the PSP detection rate. The serrated polyps with a high neoplastic potential were considered CSSPs. For the purpose of our study, all sessile serrated polyps/adenomas, all traditional serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps proximal to the rectum and sigmoid colon, and the hyperplastic polyps located in the rectum and sigmoid colon ≥5 mm in size were taken into account19.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaOnly the endoscopists that performed at least 30 colonoscopies during the study period were included in the analysis, so that the polyp detection rate would be as representative as possible, and only adult patients (≥18 years of age) participated in the study. Patients with a history of colonic resection or those that had a repeat colonoscopy during the study period (e.g., for post-polypectomy control), or patients that underwent colonoscopy that had hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysisSample size was calculated using Epidat® v.4.2 software in the sampling mode, expressed for proportion. Carrying out the indicated operations, with parameters of a 10% proportion of patients with PSPs, 3% accuracy, and a population of 15,000 patients that had outpatient gastroenterology consultation, a sample size of n = 997 was obtained.

The formula used was:

- n = sample size- Z2α = 1.962, Z value (standard normal distribution) corresponding to the desired risk

- p = expected proportion of the characteristic to be studied

- q = 1- p

- d = desired accuracy (3%)

- N = population total

Nonprobability sampling was utilized to obtain the calculated sample (n = 997).

The data were reported as absolute and relative frequencies, for the discrete or nominal variables, and as mean, standard deviation (SD), and range, for the continuous variables. The colonoscopy data of all the endoscopists that participated in the study were recorded, calculating each individual ADR (the number of colonoscopies in which ≥1 histologically confirmed adenoma was detected), PSP detection rate (the number of colonoscopies in which ≥1 serrated polyp located in the proximal colon was detected), and CSSP detection rate (the number of colonoscopies in which ≥1 CSSP, previously defined, was detected).

To compare the PSP and CSSP detection rates of each endoscopist, a multivariate logistic regression analysis corrected for patient age, sex, and bowel preparation quality was conducted. Based on those analyses, the odds ratio (OR) was calculated for the detection of ≥1 PSP or ≥1 CSSP during colonoscopy for each endoscopist, compared with the endoscopist with the highest detection rate.

The association between the ADR, PSP detection rate, and CSSP detection rate was calculated utilizing the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were carried out utilizing the SPSS® version 21 program.

ResultsOf the 1,509 colonoscopies performed within the time frame of the study, 1,413 were eligible for inclusion. Ninety-six colonoscopies were excluded because they had no BBPS score or because the pathology study results could not be found. Of the remaining 1,413, only 1,378 procedures performed by 15 endoscopists were included, each endoscopist having carried out at least 30 colonoscopies. Thirty-five colonoscopies performed by two endoscopists that carried out fewer than 30 procedures during the study period were not included. Of the 1,378 procedures included in the study, 282 corresponded to screening colonoscopies. The mean age of the patients was 57.99 (±14.26) years and 546 of the patients were men (39.6%).

A total of 555 adenomas and 267 serrated polyps were found. Bowel preparation quality was categorized as excellent (BBPS score of 8 and 9) in 654 patients (47.46%), good (BBPS score of 6 and 7) in 636 patients (46.15%), and regular/poor (BBPS score ≤ 5) in 88 patients (6.39%). The cecal intubation rate was 98.3%.

The mean ADR was 24.4% (range: 11.4-42.9%), mean PSP detection rate was 5.1% (range: 1.8-17%), and mean CSSP rate was 8.7% (range: 4.2-24.7%). Table 1 shows the colonoscopy characteristics and performance per endoscopist.

Colonoscopy performance per endoscopist.

| Endoscopist | Colonoscopies (n) | Age (±SD) | BBPS score (IQR) | Men (%) | ADR (%) | PSP (%) | CSSP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 204 | 55.97 ± 13.83 | 6 (6-9) | 43.6 | 20.6 | 2.9 | 6.4 |

| B | 136 | 61.1 ± 14.28 | 8 (7-9) | 41.2 | 25.7 | 2.9 | 6.6 |

| C | 47 | 60.36 ± 12.09 | 8 (6-9) | 34.0 | 36.2 | 17.0 | 23.4 |

| D | 43 | 58.47 ± 13.95 | 6 (6-9) | 32.6 | 30.2 | 4.7 | 7.0 |

| E | 44 | 56.25 ± 14.13 | 6 (6-9) | 50.0 | 11.4 | 2.3 | 4.5 |

| F | 30 | 64.43 ± 15.46 | 9 (6-9) | 23.3 | 33.3 | 6.7 | 11.0 |

| G | 167 | 57.40 ± 14.12 | 6 (6.8) | 31.1 | 20.4 | 1.8 | 4.2 |

| H | 95 | 54.97 ± 13.79 | 6 (6-8) | 35.8 | 23.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| I | 35 | 59.66 ± 13.41 | 9 (6-9) | 37.1 | 25.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| J | 44 | 53.14 ± 15.58 | 6 (6-7.75) | 40.9 | 22,7 | 4,5 | 9.1 |

| K | 123 | 57.29 ± 13.09 | 8 (6-9) | 41.5 | 13.8 | 4.1 | 6.5 |

| L | 196 | 57.68 ± 15.08 | 7 (6-9) | 41.8 | 24.0 | 5.1 | 9.2 |

| M | 95 | 60.91 ± 12.75 | 9 (9-9) | 41.1 | 33.7 | 9.5 | 12.6 |

| N | 42 | 55.98 ± 13.95 | 8.5 (6-9) | 45.2 | 23.8 | 7.1 | 11.9 |

| O | 77 | 61.19 ± 16.09 | 6 (6-9) | 42.9 | 42.9 | 11.7 | 24.7 |

| Total | 1378 | 57.99 ± 14.26 | 7 (6-9) | 39.6 | 24.4 | 5.1 | 8,7 |

BBPS: Boston Bowel Preparation Scale; CSSP: clinically significant serrated polyp; IQR: interquartile range; PSP: proximal serrated polyp; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the different polyp detection rates, according to preparation quality score ≥6 vs. ≤5, utilizing the BBPS. There were higher adenoma, PSP, and CSSP detection rates in the colonoscopy groups with a BPPS score ≥6, but those differences were only statistically significant for the CSSPs (p ꞊ 0.007). Table 3 shows the corrected OR for the detection of ≥1 PSP for each endoscopist, compared with the endoscopist with the highest detection rate. The range of the OR for the detection of ≥1 PSP was between 0.106 (p = 0.001, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.027-0.411) and 0.649 (p = 0.416, 95% CI: 0.229-1.839). Five endoscopists had significantly lower PSP detection rates, compared with the endoscopist with the highest detection rate.

Polyp detection rate according to bowel preparation quality.

| BBPS score ≥6 1,290 colonoscopies | BBPS score ≤5 88 colonoscopies | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADR (%) | 24.4 | 23.9 | 1.000* |

| PSP detection rate (%) | 5.3 | 2.3 | 0.314* |

| CSSP detection rate (%) | 9.1 | 3.4 | 0.007** |

ADR: adenoma detection rate; BBPS: Boston Bowel Preparation Scale; CSSP: clinically significant serrated polyp; PSP: proximal serrated polyp.

OR for the detection of ≥1 PSP, compared with the endoscopist with the highest detection rate.

| Endoscopists | p | OR for detection of ≥1 PSP (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| C | 1 | 1 |

| A | 0.002 | 0.175 (0.0057-0.540) |

| B | 0.002 | 0.141 (0.040-0.494) |

| D | 0.104 | 0.261 (0.052-1.315) |

| E | 0.058 | 0.127 (0.015-1.072) |

| F | 0.176 | 0.323 (0.063-1.657) |

| G | 0.001 | 0.106 (0.027-0.411) |

| H | 0.053 | 0.282 (0.078-1,017) |

| I | 0.129 | 0.284 (0.056-1.441) |

| J | 0.147 | 0.300 (0.059-1.526) |

| K | 0.012 | 0.219 (0.067-0.712) |

| L | 0.013 | 0.281 (0.104-0.763) |

| M | 0.142 | 0.461 (0.164-1.296) |

| N | 0.198 | 0.398 (0.098-1.621) |

| O | 0.416 | 0.416 (0.229-1.839) |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PSP: proximal serrated polyp.

Table 4 shows the corrected OR for the detection of ≥1 CSSP for each endoscopist, compared with the endoscopist with the highest detection rate. The range of the OR for the detection of ≥1 CSSP was between 0.160 (p = 0.000 and 95% CI: 0.063-0.405) and 0.919 (p = 0.848 and 95% CI: 0.386-2.18). Nine endoscopists had a significantly lower CSSP detection rate, compared with the endoscopist with the highest detection rate.

OR for the detection of ≥1 CSSP, compared with the endoscopist with the highest detection rate.

| Endoscopists | p | OR for the detection of ≥1 CSSP (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| O | 1 | 1 |

| A | 0.001 | 0.251 (0.115-0.547) |

| B | 0.000 | 0.198 (0.083-0.469) |

| C | 0.848 | 0.919 (0.386-2.18) |

| D | 0.036 | 0.250 (0.068-0.912) |

| E | 0.20 | 0.165 (0.036-0.756) |

| F | 0.071 | 0.296 (0.079-1.111) |

| G | 0.000 | 0.160 (0.063-0.405) |

| H | 0.004 | 0.184 (0.058-0.577) |

| I | 0.024 | 0.172 (0.037-0.794) |

| J | 0.138 | 0.412 (0.127-1.330) |

| K | 0.001 | 0.224 (0.091-0.549) |

| L | 0.003 | 0.329 (0.160-0.678) |

| M | 0.021 | 0.382 (0.169-0.866) |

| N | 0.136 | 0.438 (0.148-1.297) |

CI: confidence interval; CSSP: clinically significant serrated polyp; OR: odds ratio.

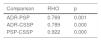

Table 5 shows the correlation between the ADR, the PSP detection rate, and the CSSP detection rate. There was a strong correlation between the PSP detection rate and the ADR (p = 0.769; p = 0.001), as well as a strong correlation between the CSSP detection rate and the ADR (p = 0.789; p = 0.000). Finally, the correlation between the PSP detection rate and the CSSP detection rate was almost perfect (p = 0.922; p = 0.000).

Discussion and conclusionsIn recent years, the malignant potential of serrated polyps has been recognized. Said lesions may not be detected due to their particular characteristics, such as indistinguishable edges, flat morphology, or the presence of a layer of mucus on their surface. Good bowel preparation is essential for adequate detection26,27. In our study, bowel preparation quality was excellent/good (BBPS score ≥6) in 93.61% of the patients, which facilitated adequate detection. Upon evaluating the polyp detection rates, according to bowel preparation quality, we found higher adenoma, PSP, and CSSP detection rates in the patients with a BBPS score ≥6 vs. a BBPS score ≤ 5, but statistical significance was reached only in relation to CSSPs, with a p ꞊ 0.007.

The ADR was 24.4%, with wide variability between endoscopists (range: 11.4-42.9%), as has already been reported in previous studies28,29, and is related to differences in the exploration technique. Chen and Rex utilized specific criteria for evaluating endoscopist performance: observation of the proximal sides of folds and valves, adequate cleansing, adequate distension, and appropriate evaluation time. They found that the endoscopist that had better technical withdrawal had a lower missed polyp rate. In that context, the present study showed that the PSP detection rate also varied widely between endoscopists. The PSP detection rate ranged from 1.8 to 17% (an average of 5.1%), whereas the CSSP detection rate ranged from 4.2 to 24.7% (an average of 8.7%). There was an almost perfect correlation between the PSP detection rate and the CSSP detection rate (p = 0.922; p = 0.000), indicating the interchangeability of those parameters. Likewise, there was a statistically significant correlation between the PSP detection rate and the ADR (p = 0.769; p = 0.001), and between the CSSP detection rate and the ADR (p = 0.789; p = 0.000), as well, albeit with less strength of association.

Those findings suggest that the PSP detection rate is a potential parameter of quality in colonoscopy, comparable with the detection rate of all clinically relevant serrated polyps. Ideally, the evaluation of all clinically relevant serrated polyps should be based on the CSSP detection rate, instead of the PSP detection rate. However, the histopathologic characterization of serrated polyp subtypes is difficult, and the diagnosis by expert and non-expert pathologists can differ widely in clinical practice. When the PSP detection rate, rather than the CSSP detection rate, is used, there is a lower risk for biased results, caused by incorrect typing of serrated polyps on the part of the pathologist, not affecting the measurement of all polyps located in the proximal colon. In our study, the PSP and CSSP detection rates had an almost perfect correlation.

One of the strengths of the present study was its adequate sample size, for arriving at significant conclusions. Another was the fact that we included the important colonoscopy quality indicator of bowel preparation quality, utilizing the validated BBPS score. In addition, all the participating endoscopists were experienced in colonoscopy. Another strength of the study was the exclusion of subjects with hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease, which are diseases that increase the number of pre-neoplastic lesions.

The limitations of our study include the fact that the colonoscopies of the participating patients were performed for different indications, in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, which could have favored the great variability in the serrated polyp detection rate between endoscopists. Nevertheless, the majority of the colonoscopies were carried out in symptomatic patients. On the other hand, withdrawal time, which, as we know, is related to the polyp detection rate, was not recorded. A total of 6.39% of the cases had inadequate bowel preparation, which could have affected polyp detection in those patients. And finally, even though three expert pathologists participated in our study, the slides were not reviewed to corroborate the agreement of their observations, especially in relation to the diagnosis of the serrated lesions.

Our results are in line with those of other studies, four of which were conducted on asymptomatic populations and one on a population of both symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects, showing similar differences in PSP detection between endoscopists. In the retrospective study conducted by Kahi et al.17, the PSP detection rate was in the range of 1 to 18%, between 15 endoscopists. In the prospective study by Wijkerslooth et al.18, the PSP detection rate ranged from 6 to 22%, between five endoscopists, and Bretagne et al.20 also reported PSP detection rates that ranged from 1.28 to 19.25%, between 18 endoscopists. More recently, Mandaliya et al. reported variations in the PSP detection rate ranging from 1.1 to 22%21. All those studies were performed on populations undergoing screening. In the cross-sectional study by Ijspeert et al.19, on a population that was both symptomatic and asymptomatic (such as ours), the PSP detection rate varied from 2.9 to 18.6%, between 16 endoscopists. We had similar results, with a PSP detection rate that ranged from 1.8 to 17%, between 15 endoscopists. Those results suggest that the prevalence of PSPs is similar in patients undergoing screening and those in a mixed population (screening and symptomatic subjects).

We also evaluated the association between the PSP detection rate and the ADR, finding a strong correlation (0.769; p = 0.001), similar to that reported by Kahi et al.17 (0.86; p < 0.001) and greater than that described by Ijspeert19 (0.55; p = 0.03). Those results suggest that the endoscopists with a high ADR would also better evaluate the mucosa of the colon, achieving a higher detection rate for all polyps, including PSPs. Two studies add strength to that assumption, by showing a significant association between the serrated polyp detection rate and the corrected withdrawal time, which could indicate that the endoscopists with higher polyp detection rates, carry out a more thorough inspection of the colon18,30. We believe that the ADR cannot be viewed as an indirect indicator of the CSSP detection rate, because even though the correlation between the ADR and the PSP detection rate was strong, as was that of the ADR and the CSSP detection rate, it did not reach the almost perfect rate that the correlation between the PSP detection rate and the CSSP detection rate did, indicating that both the ADR and the PSP detection rates of an endoscopist should be sufficiently high for a colonoscopy to be considered high quality. Our results concur with those of a prospective study that evaluated the correlation of the PSP detection rate and the ADR between 31 centers, finding only a moderate correlation (0.43; p = 0.03)31.

In conclusion, our study showed that the PSP detection rate varied widely between the endoscopists and had an almost perfect correlation with the CSSP detection rate. Therefore, measurements of the PSP detection rate and the ADR appear to be parameters that ensure a high-quality colonoscopy. Nevertheless, future studies are needed to determine the relation between the PSP detection rate and the risk for interval cancer.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that no experiments on animals or humans were conducted in the present study and it was approved by the Teaching and Training Office of the Policlínico Peruano Japonés, following its protocols on the publication of patient data. Likewise, standard care was provided to the patients and no interventions were performed. Therefore, no statements of informed consent were required.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank the physicians, nurses, and technical and administrative personnel of the Gastroenterology Service of the Policlínico Peruano Japonés for their generous support, and Felix Armando Barrientos Achata for his support regarding the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Parra-Pérez VF, Watanabe Yamamoto J, Nago-Nago A, Astete-Benavides M, Rodríguez-Ulloa C, Valladares-Álvarez G, et al. Correlación entre la detección de pólipos serratos proximales y pólipos serratos clínicamente significativos: variabilidad interendoscopista. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2021;86:348–355.