Identifying persons at high risk for advanced colorectal neoplasia can aid in the prevention of colon cancer. Previous studies have shown that some patients can present with proximal advanced neoplasia with no distal findings.

AimsTo determine the factors related to advanced neoplasia and advanced proximal colorectal neoplasia in a Latin American population.

Material and methodsA prospective, cross-sectional, observational, analytic study was conducted. It included patients that underwent colonoscopy at the Policlínico Peruano Japonés within the time frame of January and July 2012. Advanced neoplasia was defined as the presence of lesions ≥ 10mm with a villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or carcinoma. The splenic flexure was the limit between the proximal and distal colon.

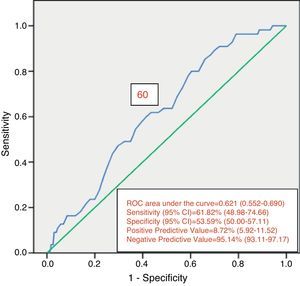

ResultsA total of 846 patients were included in the study. Advanced neoplasia was detected in 108 patients (12.8%) and advanced proximal neoplasia in 55 patients (6.7%), 42 (76.4%) of whom had no neoplasia in the distal colon. Factors related to advanced neoplasia found in the multivariate analysis were age, at the intervals of 50-59 (p=0.019), 60-69 (p=0.016), and ≥ 70 years (0.002) and male sex (p=0.003). In the evaluation of advanced proximal neoplasia, the multivariate analysis identified the 60-69 year age interval (p=0.039) and advanced distal neoplasia (p=0.028) as factors related to advanced proximal disease. The ROC curve established the age cut-off point at 60 years for initially performing colonoscopy, rather than sigmoidoscopy.

ConclusionsAge and sex are related to advanced neoplasia, whereas age and advanced distal neoplasia are related to advanced proximal neoplasia.

Identificar personas con alto riesgo de neoplasia avanzada colorrectal puede ayudar en la prevención de cáncer de colon. Por otro lado, estudios previos han observado que algunos pacientes pueden tener neoplasia avanzada proximal sin hallazgos distales.

ObjetivoDeterminar los factores relacionados a neoplasia avanzada y neoplasia avanzada proximal colorrectal en una población latinoamericana.

Material y métodosEstudio analítico, observacional, transversal y prospectivo. Se incluyó a pacientes sometidos a colonoscopia en el Policlínico Peruano Japonés entre enero y julio del 2012. Se definió neoplasia avanzada como la presencia de lesiones ≥ 10mm en tamaño, con componente velloso o displasia de alto grado o carcinoma. El límite entre el colon proximal y distal fue el ángulo esplénico.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 846 pacientes. Se detectó neoplasia avanzada en 108 pacientes (12.8%). Se detectó neoplasia avanzada proximal en 55 pacientes (6.7%), de los cuales 42 (76.4%) tuvieron el colon distal sin neoplasias. El análisis multivariado encontró como factores relacionados a neoplasia avanzada a la edad, en intervalos 50-59 (p=0.019), 60-69 (p=0.016) y ≥ 70 años (0.002) y el género masculino (p=0.003). Al evaluar neoplasia avanzada proximal, el análisis multivariado encontró a la edad en intervalo de 60-69 años (p=0.039) y la neoplasia avanzada distal (p=0.028) como relacionados. La curva ROC estableció un corte de edad de 60 años para realizar colonoscopia de inicio en lugar de sigmoidoscopia.

ConclusionesLa edad y el género están relacionados con neoplasia avanzada, mientras que la edad y la neoplasia avanzada distal están relacionadas a neoplasia avanzada proximal

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in men and the second most common in women worldwide, with more than 1.2 million new cases and more than 600,000 deaths annually.1

Colorectal cancer screening in the general population can reduce the colorectal cancer mortality rate. The international guidelines recommend this screening from the age of 50 years, through tests such as fecal occult blood, sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy.2 However, these recommendations are not always observed. One of the main barriers to screening is the lack of risk perceived by the patients and even by the primary care physicians.3,4 The risk for colorectal cancer or advanced neoplasia (AN) in general, varies according to several factors, including age,5–9 sex,6–10 a family history of colon cancer,6,8,9,11 tobacco smoking,8,9,12,13 obesity,7,9,14 diabetes mellitus,15 etc. Information on these factors is easy to obtain and could be used to identify those patients at high risk for AN that would benefit most from screening.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is a simple screening method for colorectal cancer. Not only does it reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer, but it reduces the mortality rate, as well. A large randomized study reported that sigmoidoscopy alone, performed in patients between the ages of 55 and 64 years, reduced the incidence of colorectal cancer by 33% and the colorectal cancer mortality rate by 43% during a mean 11.2-year follow-up period.16 The addition of a yearly fecal occult blood test to sigmoidoscopy has been reported to have little or no benefit.17,18 To the contrary, it can reduce screening participation.19,20

Nevertheless, despite the strong evidence of the clinical benefits of sigmoidoscopy, this procedure does not enable proximal colon evaluation. A complementary colonoscopy must be performed if the sigmoidoscopy result indicates the presence of distal neoplasia, especially if it is greater than 1cm, if it has a villous histology, or if there are multiple neoplasia, given that these are risk factors for proximal advanced neoplasia (PAN).5,21–27 The prevalence of PAN varies between 1.7 and 5.4%, according to published studies.5,22,23,27,28 However, 60 to 70% of the patients with PAN do not present with distal neoplasia.5,22,29–31 Therefore, these patients with PAN could go undetected if colonoscopy is performed based solely on the previous sigmoidoscopy findings. Ideally, proximal colon examination should be selectively carried out on patients at high risk for PAN, based on a stronger predictive model that includes sigmoidoscopy findings and clinical risk factors. However, there have been few studies on this subject.21,23,25,29,30,32,33 The aim of our study was to determine the factors related to colorectal AN and PAN.

MethodsThis is an analytic, observational, cross-sectional, prospective study and was approved by the Office of Training, Research and Teaching of the Policlínico Peruano Japonés. It included all the outpatients that underwent colonoscopy at the Gastroenterology Service of the Policlínico Peruano Japonés within the time frame of January to July 2012. The Policlínico Peruano Japonés is a private institution and the majority of its patients are outpatients. A total of 14 experienced gastroenterologists performed the procedures. The colonoscopies were carried out with Olympus equipment, models CF-H 180, CF-Q 160 ZL, CF-H 150, and CF-Q 150 and Fujinon equipment, model EC-590 WL. All the procedures were recorded and archived. Patients under the age of 16 years and those that did not have an anatomopathologic study were excluded. All the patients received verbal and written instructions for intestinal preparation and the divided dose system was used for all the procedures. The colon cleansing preparations used were polyethylene glycol (PEG) in its presentation of envelopes containing 105g of PEG 3350 and sodium phosphate (in 45ml bottles that contained 48g of monobasic sodium phosphate and 18g of dibasic sodium phosphate per each 100ml). If the examination was to be performed in the morning, the patient was instructed to take 3 PEG envelopes the night before and one in the morning, or one bottle of sodium phosphate the night before and another in the morning. If the examination was in the afternoon, the patient was instructed to take 2 PEG envelopes the night before and 2 envelopes the morning of the exam or one bottle of sodium phosphate the night before and another bottle the morning of the exam.

Before the procedure, the patients were interviewed and the following information was collected:

- 1.

Demographic data: age, sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and educational level.

- 2.

Personal medical history, including past medical history (diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disorder, cirrhosis, antidepressive/anti-anxiety drug use, current tobacco smoker, number of bowel movements per week, abdominal surgery, a history of prior colonoscopy, polyps, or colon cancer, and a family history of colon cancer).

- 3.

Colonoscopy indication: for diagnostic purposes (patient with symptoms such as abdominal pain, hematochezia, rectorrhagia, chronic diarrhea, constipation, or anemia in study), screening or follow-up (post-polypectomy or surgical resection for colon cancer).

- 4.

Bowel preparation characteristics: the use of PEG or sodium phosphate and the addition of a laxative.

- 5.

Adverse effects experienced during the preparation: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating, anal irritation, or sleep disorder.

Data on the following colonoscopy-related variables were collected during the procedure: the time at which the study was begun, withdrawal time, findings, and bowel preparation quality. The time of colonoscopy was classified as “morning” if it was performed between 08:00 am and 11:59 am or “afternoon” if it was performed between 12:00 pm and 06:00 pm. Bowel preparation quality was registered by the endoscopist in charge of the procedure and categorized as excellent (adequate visualization of the entire colon with no washout or suction), good (adequate visualization of more than 90% of the colon with clear fluids requiring minimum suction and minimum or no washout), regular (unsatisfactory visualization of all or part or the colon with dark fluid and liquid feces that required suction and washout), and poor (unsatisfactory visualization of all or part of the colon, with dark fluid and feces requiring suction and washout and the need to consider re-examination) based on the predefined Aronchick scale.34,35 For the purposes of our study we redefined the level of preparation as “optimum” (excellent or good) or “suboptimum” (regular or poor). If elevated lesions were found, the corresponding histopathologic report was obtained after the procedure.

Conventional colonoscopy was performed by experienced gastroenterologists. Complete colonoscopy was considered when the colonoscope reached the cecum. During the colonoscopy, the location and size of all the polyps were determined before their removal. Size was measured comparing the lesion with the open biopsy forceps or based on clinical judgment. Lesion location was determined by the clinical judgment of the gastroenterologist.

The splenic flexure was established as the limit between the proximal and distal colon.22,23,29,31,36,37 The definition of AN was the presence of lesions larger than 10mm with a villous component or with high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma.8,23,29,37 Cancer was defined as the invasion of malignant cells under the muscularis mucosae.31 For purposes of the analysis, traditional serrated adenomas, serrated sessile lesions, and mixed serrated polyps were categorized as tubular adenomas.9 Polyps under 10mm that were not extirpated, were regarded as non-neoplastic.9 If the patient had more than one lesion, whether in the proximal or distal colon, the more advanced lesion was the one classified.

Data were reported as absolute and relative frequencies for discrete or nominal variables, and as means, standard deviation (SD), and range for the continuous variables. These data were analyzed using the SPSS version 16.0 statistical package and the tables were constructed using the Excel program. The variables were crossed by means of 2 x 2 tables. Each variable was studied for its association with the presence of AN and PAN. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test were used for the categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for the continuous variables. Age was evaluated as a continuous and categorical variable (< 40, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, and ≥ 70). BMI was categorized as ≥ 30 (obese) and < 30 (not obese). The variables that were significantly associated with AN and PAN in the univariate analysis then underwent multivariate analysis using logistic regression.

The patients that had incomplete colonoscopy were excluded from the analysis of risk factors for PAN.

ResultsA total of 846 colonoscopies that fit the inclusion criteria were performed during the study period. The mean age was 57.67 years (SD ± 14.77), 71.6% of the patients were above 50 years of age, and 64.9% were women. A total of 119 (14.1%) of the patients were obese (BMI ≥ 30). The most frequent indication for the examination was for diagnostic purposes (59.1%). A total of 112 (13.2%) patients had a family history of colon cancer and 291 (34.4%) had undergone previous colonoscopy. Of the 846 colonoscopies performed, the cecum was reached in 822 (97.1%). In 54.1% of the colonoscopies, the withdrawal time was greater than or equal to 6min. In 6 colonoscopies, polyps under 10mm that had a hyperplastic aspect and were located in the rectum were not removed at the discretion of the endoscopist.

Some type of colonic neoplasia was detected during colonoscopy in 243 (28.7%) patients, 223 (26.4%) of which corresponded to adenomas and 20 (2.4%) to cancer. A total of 108 (12.8%) patients presented with AN (Table 1).

Factors related to AN through the univariate analysis in the total number of patients were age (p = 0.002) and male sex (p = 0.012) (Table 2).

Factors related to the univariate analysis-AN.

| Characteristics | Patient total No.=846 | AN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p | ||

| Age, years ± SD | 57.67 ± 14.77 | 63.69 ± 13.20 | 56.79 ± 14.79 | 0.000c |

| Age, n (%) | 0.002b | |||

| < 40 | 102 (12.1) | 5 (4.6) | 97 (13.1) | |

| 40-49 | 138 (16.3) | 9 (8.3) | 129 (17.5) | |

| 50-59 | 199 (23.5) | 28 (25.9) | 171 (23.2) | |

| 60-69 | 213 (25.2) | 30 (27.8) | 183 (24.8) | |

| ≥ 70 | 194 (22.9) | 36 (33.4) | 158 (21.4) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Men | 297 (35.1) | 50 (46.3) | 247 (33.5) | 0.012a |

| Women | 549 (64.9) | 58 (53.7) | 491 (66.5) | |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 26.02 ± 4.02 | 26.13 ± 3.75 | 26.00 ± 4.06 | 0.629c |

| BMI ≥ 30, n (%) | 119 (14.1) | 15 (13.9) | 104 (14.1) | 1.000a |

| BMI < 30, n (%) | 727 (85.9) | 93 (86.1) | 634 (85.9) | |

| Time of the examination, n (%) | ||||

| “Morning” | 350 (41.4) | 43 (39.8) | 307 (41.6) | 0.805a |

| “Afternoon” | 496 (58.6) | 65 (60.2) | 431 (58.4) | |

| Current tobacco smoking, n (%) | 330 (39.0) | 51 (47.2) | 279 (37.8) | 0.077a |

| Personal history of polyps, n (%) | 101 (11.9) | 14 (13.0) | 87 (11.8) | 0.847a |

| Previous colonoscopy, n (%) | 291 (34.4) | 36 (33.3) | 255 (34.6) | 0.888a |

| Family history of colon cancer, n (%) | 112 (13.2) | 19 (17.6) | 93 (12.6) | 0.201a |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 62 (7.3) | 9 (8.3) | 53 (7.2) | 0.817a |

| Bowel movements per week, n (%) | ||||

| 1-3 | 67 (7.9) | 6 (5.6) | 61 (8.3) | 0.620b |

| 4-6 | 155 (18.3) | 20 (18.5) | 135 (18.3) | |

| 7 or more | 624 (73.8) | 82 (75.9) | 542 (73.4) | |

| Enema received, n (%) | ||||

| Polyethylene glycol | 770 (91.0) | 98 (90.7) | 672 (91.1) | 1.000a |

| Sodium phosphate | 76 (9.0) | 10 (9.3) | 66 (8.9) | |

| Quality of bowel preparation, n (%) | ||||

| Optimum | 405 (47.9) | 47 (43.5) | 358 (48.5) | 0.386a |

| Suboptimum | 441 (52.1) | 61 (56.5) | 380 (51.5) | |

| Colonoscopy indication, n (%) | ||||

| Diagnostic | 500 (59.1) | 61 (56.5) | 439 (59.5) | 0.297b |

| Screening | 257 (30.4) | 31 (28.7) | 226 (30.6) | |

| Follow-up | 89 (10.5) | 16 (14.8) | 73 (9.9) | |

AN: advanced neoplasia; SD: standard deviation.

The multivariate analysis confirmed a statistically significant association of age in the ranges of 50-59 (p = 0.019), 60-69 (p = 0.016), and ≥ 70 years (p = 0.002), as well as in the male sex (p = 0.003) (Table 3) with AN.

Of the 822 patients that had complete examination of the colon, 99 (12.0%) presented with AN. Of those patients, 55 presented with PAN. Of the PAN group, 42 (76.4%) had no neoplastic lesion in the distal colon. Despite this fact, findings in the distal colon can predict the presence of PAN (Table 4). The presence of ≥ 3 distal non-advanced neoplasias or distal AN increased the risk for PAN almost 2.5-fold. The univariate analysis found age (p = 0.047) and the presence of distal AN (p = 0.018) as significant factors related to the presence of PAN (Table 5). The multivariate analysis confirmed the significant association of age at the interval of 60-69 years (p = 0.039) and the presence of distal AN (p=0.028), with the presence of PAN (Table 6). The ROC curve generated from age and the presence of PAN (fig. 1) showed an area under the curve of 0.621 and the cut-off point of 60 years was the one that best distinguished the need for initial colonoscopy rather than sigmoidoscopy.

Risk for PAN according to distal findings (n = 822).

| Distal findings | No. of patients | PAN = 55 | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | % | |||

| No distal neoplasia | 692 | 42 | 6.1 | Reference |

| 1-2 distal non-advanced neoplasias | 73 | 5 | 6.8 | 1.028 (0.397-2.664) |

| ≥ 3 distal non-advanced neoplasias or some distal AN | 57 | 8 | 14.0 | 2.494 (1.117-5.570) |

| Distal AN | 52 | 8 | 15.4 | 2.797 (1.245-6.281) |

AN: advanced neoplasia; PAN: proximal advanced neoplasia.

Factors related to the univariate analysis-PAN.

| Characteristics | Patients with cecal intubation N = 822 | PAN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p | ||

| Age, years ± SD | 57.39 ± 14.67 | 63,29 ± 11.93 | 56.96 ± 14.77 | 0.003d |

| Age, n (%) | 0.047c | |||

| < 40 | 101 (12.3) | 2 (3.6) | 99 (12.9) | |

| 40-49 | 136 (16.5) | 4 (7.3) | 132 (17.2) | |

| 50-59 | 195 (23.7) | 15 (27.3) | 180 (23.5) | |

| 60-69 | 208 (25.3) | 19 (34.5) | 189 (24.6) | |

| ≥ 70 | 182 (22.1) | 15 (27.3) | 167 (21.8) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Women | 532 (64.7) | 31 (56.4) | 501 (65.3) | 0.231a |

| Men | 290 (35.3) | 24 (43.6) | 266 (34.7) | |

| BMI mean ± SD | 26.02 ± 3.99 | 26.56 ± 3.82 | 25.98 ± 4.01 | 0.243a |

| BMI ≥ 30, n (%) | 114 (13.9) | 8 (14.5) | 106 (13.8) | 1.00a |

| BMI < 30, n (%) | 708 (86.1) | 47 (85.5) | 661 (86.2) | |

| Time of the examination, n (%) | ||||

| “Morning” | 342 (41.6) | 21 (38.2) | 321 (48.9) | 0.695a |

| “Afternoon” | 480 (58.4) | 34 (61.8) | 446 (51.1) | |

| Current tobacco smoking, n (%) | 317 (38.6) | 26 (47.3) | 291 (37.9) | 0.219a |

| Personal history of polyps, n (%) | 100 (12.2) | 9 (16.4) | 91 (11.9) | 0.440a |

| Previous colonoscopy, n (%) | 284 (34.5) | 23 (41.8) | 261 (34.0) | 0.305a |

| Family history of colon cancer, n (%) | 109 (13.3) | 11 (20.0) | 98 (12.8) | 0.187a |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 58 (7.1) | 4 (7.3) | 54 (7.0) | 1.000b |

| Bowel movements per week, n (%) | ||||

| 1-3 | 66 (8.0) | 2 (3.6) | 64 (8.3) | 0.381c |

| 4-6 | 153 (18.6) | 9 (16.4) | 144 (18.8) | |

| 7 or more | 603 (73.4) | 44 (80.0) | 559 (72.9) | |

| Enema received, n (%) | ||||

| Polyethylene glycol | 750 (91.2) | 51 (92.7) | 699 (91.1) | 1.000b |

| Sodium phosphate | 72 (8.8) | 4 (7.3) | 68 (8.9) | |

| Quality of bowel preparation, n (%) | ||||

| Optimum | 395 (48.1) | 26 (47.3) | 369 (48.1) | 1.000a |

| Suboptimum | 427 (51.9) | 29 (52.7) | 398 (51.9) | |

| Colonoscopy indication, n (%) | ||||

| Diagnostic | 489 (59.5) | 30 (54.5) | 459 (59.8) | 0.120c |

| Screening | 250 (30.4) | 15 (27.3) | 235 (30.6) | |

| Follow-up | 83 (10.1) | 10 (18.2) | 73 (9.5) | |

| Presence of distal AN, n % | 52 (6.3) | 8 (14.5) | 44 (5.7) | 0.018b |

AN: advanced neoplasia; PAN: proximal advanced neoplasia; SD: standard deviation.

Factors related to the multivariate analysis-PAN.

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| < 40 | 1.000 | - | - |

| 40-49 | 1.486 | 0.267-8.287 | 0.651 |

| 50-59 | 3.920 | 0.876-17.533 | 0.074 |

| 60-69 | 4.762 | 1.085-20.903 | 0.039 |

| ≥ 70 | 4.143 | 0.925-18.565 | 0.063 |

| Presence of distal AN | 2.499 | 0.742-3.884 | 0.028 |

AN: advanced neoplasia; PAN: proximal advanced neoplasia.

Our study confirmed the results of previous analyses that showed age and male sex as factors associated with AN.

We preferred to evaluate AN rather than cancer, given that previous studies suggested that this was a more adequate aim in relation to colonoscopy screening.5–10,13,28 Nevertheless, some predictive models exclusively for cancer38–40 have previously been developed and both cancer and AN are important study aims for colon cancer screening that will enable the colorectal cancer mortality rate to be reduced. Early colorectal cancer detection and treatment are associated with reduced colorectal cancer mortality,9 but detection and removal of adenomas, especially those that are advanced, are also associated with reduced colorectal cancer incidence.41,42

Age and sex were found to be important risk factors for the development of advanced colorectal neoplasia. Men have almost double the risk for developing advanced neoplasia, compared with women. There was also a significant association between age and advanced neoplasia. Patients above the age of 70 years, in particular, have a 4-fold greater risk compared with those under 40 years of age. Greater colorectal neoplasia prevalence associated with age has been observed in previous studies.13,26 Other factors, such as a family history of colorectal cancer, tobacco smoking, and BMI were not related to advanced colorectal neoplasia in our study, unlike that reported by Kaminski et al.9

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is generally well-tolerated, easy to perform, safe and economic.16 Thus, sigmoidoscopy is an adequate initial large-scale screening test for colorectal cancer. Nevertheless, sigmoidoscopy cannot evaluate the proximal colon and therefore studies have been conducted to identify factors related to proximal neoplasia that could be used to identify patients that would need complementary colonoscopy. Findings in the distal colon (large neoplasms or histologically advanced neoplasia) have been identified as risk factors for PAN, along with some clinical characteristics (age, male sex, obesity, alcohol ingestion or tobacco smoking, and a family history of colorectal cancer).21–23,27,29–33,37

We also evaluated factors related to PAN. For that analysis, only the colonoscopies in which cecal intubation was achieved were taken into account.31 Age and the presence of distal AN were found to be related, but not sex. In regard to age, it was preferable for initial colonoscopy to be performed, rather than sigmoidoscopy, in patients above the age of 60 years, due to the high risk for finding PAN in that group of patients. With respect to distal AN, there was a 2.5-fold increased risk. This concurred with the findings of Leung et al.,31 who found a 3.9-fold risk increase in that group of patients. Other findings in the distal colon, such as non-advanced neoplasias, were not statistically significant in relation to PAN, which perhaps was due to the small size of our study sample.

In the present study, 6.1% of the patients with no neoplasia in the distal colon presented with PAN. Alternatively, 76.4% of the patients with proximal advanced lesion had no neoplasia in the distal colon. These results are related to those of previous reports.13,22,29,31,32 It can be deduced from these findings that three-quarters of advanced colonic lesions could be missed in sigmoidoscopy, if colonoscopy were not performed in patients presenting with no neoplasia in the distal colon.

Our definition of AN was the same as that used in the majority of the previous studies, and it included adenomas > 1cm.5,9,13,25,26,29–31,33,37 Given that polyp size determination can be subject to wide interobserver variability, a more rigorous definition without considering size, such as that proposed by Imperiale et al.,22 could prevent such a discrepancy. Therefore our AN detection rate can be different, when compared with that of Imperiale.

Among the limitations of our study is the small sample size. This was probably the reason that no other risk factors for advanced neoplasia were identified, such as a family history of colon cancer, tobacco smoking, obesity, and diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, we did not take other risk factors into account, such as aspirin use. Likewise, our risk factors only predicted advanced neoplasia detection at the time of evaluation, and not the future risk for developing advanced colorectal neoplasia or death from colorectal cancer. In addition, like Dodou and Winter24 and Chung et al.,25 we considered both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, which can distort the comparisons with other studies that only evaluated patients for screening5–9,13,21–23,29,30,33,37 or symptomatic patients.31,36

In conclusion, our study found that age and sex were related to the presence of advanced colorectal neoplasia, and that age and distal AN were related to PAN. In particular, patients above the age of 60 years would require initial colonoscopy, as opposed to sigmoidoscopy for colon evaluation. Future studies with larger samples are necessary in order to find other related factors and to establish a score for identifying individuals at high risk for presenting with advanced colorectal neoplasia.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank Felix Armando Barrientos-Achata for his help with the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Parra-Pérez V, Watanabe-Yamamoto J, Nago-Nago A, Astete-Benavides M, Rodríguez-Ulloa C, Valladares-Álvarez G, et al. Factores relacionados a neoplasia avanzada colorrectal en el Policlínico Peruano Japonés. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2015;80:239–247.

See related content at doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rgmx.2015.09.001, Blancas Valencia JM. ¿Debemos olvidar la rectosigmoidoscopia para el diagnóstico de neoplasia avanzada colorrectal? Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2015;80(4):237-8.