Foreign body (FB) ingestion is a common problem in children under 5 years of age and is one of the main indications for endoscopy. The aim of the present study was to describe the clinical, radiographic, and endoscopic characteristics of patients with FB ingestion, as well as the factors associated with the anatomic location and the type of object ingested.

Materials and methodsAn analytic cross-sectional study was conducted on all patients with FB ingestion seen at the gastroenterology service from January 2013 to December 2018. The data were analyzed using the SPSS program, obtaining frequencies, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges. Associations were assessed through the chi-square test.

ResultsEighty-five patients (52 males and 33 females) were included, with a median age of 4 years. The most common symptom was vomiting (29.4%). Two radiographic projections were carried out in 72.9% of the cases and the stomach was the site where the FB was most frequently visualized (32.9%). The objects most commonly ingested were coins (36%), with esophageal location (p<0.05), as well as objects with a diameter larger than 2cm (p<0.05). An endoscopic procedure was performed on 76 patients (89.4%) for FB extraction, with findings of erythema (28.9%), erosion (48.6%), ulcer (10.5%) and perforation (1.3%).

ConclusionsNumerous factors should be taken into account in the approach to FB ingestion in pediatric patients, including type and size of the FB, time interval from ingestion to hospital arrival, and patient clinical status and age.

La ingestión de cuerpo extraño (CE) es un problema común en niños menores de 5 años, siendo una de las principales indicaciones para realizar endoscopias. El propósito de este estudio es describir las características clínicas, radiográficas y endoscópicas de pacientes con ingesta de CE, así como factores asociados con la localización anatómica y el tipo de objeto ingerido.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal analítico del total de pacientes con ingesta de CE en el servicio de gastroenterología de enero de 2013 a diciembre de 2018. Los datos se analizaron con el programa SPSS®, y se obtuvieron frecuencias, porcentajes, medianas, rangos intercuartílicos y, además, se buscaron asociaciones mediante Chi-cuadrado.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 85 pacientes, 52 varones y 33 mujeres, la mediana de edad fue de 4 años. El síntoma más común fue el vómito (29.4%). En el 72.9% de los casos se realizaron dos proyecciones radiográficas, siendo el estómago el sitio donde se visualizó con más frecuencia (32.9%). Los objetos más comúnmente ingeridos fueron monedas (36%) con localización principalmente esofágica (p<0.05) así como objetos con diámetro mayor a 2cm (p<0.05). En 76 pacientes (89.4%) se realizó algún procedimiento endoscópico para su extracción, encontrando eritema (28.9%), erosiones (48.6%), úlceras (10.5%) y perforación (1.3%).

ConclusionesEn el abordaje por ingesta de CE en pacientes pediátricos, deben tenerse en cuenta numerosos factores, incluyendo tipo y tamaño del CE, tiempo transcurrido desde la ingesta, estado clínico y edad del paciente.

Foreign body (FB) ingestion in children is a serious and common problem worldwide1, and is considered an important indication for endoscopy2. In the United States, 66,519 cases of FB ingestion were reported in 20183, and the majority occurred in children between 6 months and 3 years of age4. Male sex is described as predominant5. At least 98% of FB ingestions in children are accidental, which is very different from the rate in adults. Intentional ingestions in older children and adults can be the result of psychiatric deterioration (self-harm, suicidal ideation) or disability6.

Coins are the most common FBs ingested by children, accounting for up to 60% of all cases7. Small toys, food bolus impaction, marbles, magnets, buttons, and coin cell and button cell batteries are other FBs ingested by children6–8.

Between 20 and 38% of children with FBs in the esophagus are completely asymptomatic9,10. A variety of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with FB ingestion are vomiting, nausea, odynophagia, dysphagia, and sialorrhea and respiratory symptoms include cough and wheezing11. Some children refer to the sensation of pressure or pain in the neck, chest, or abdomen. Patients can present with vomiting, reject foods, or be irritable. Esophageal perforation can be characterized by edema or neck crepitus12. A FB in the esophagus can easily compress the posterior membranous wall of the trachea or larynx and produce cough, wheezing, whistling, or choking10,13. The presence of abdominal pain, rigidity, or rebound can be a sign of intestinal perforation14,15.

After completing the physical examination, x-rays are often used in the complementary evaluation of a patient suspected of having FB ingestion15. Establishing whether the ingested object is radiolucent or radiopaque is important. Chest X-rays, including the posterior-anterior projections, as well as the lateral projections, can be useful in locating some radiopaque objects, but can miss objects that are above the chest or that pass into the pylorus. Therefore, abdominal and neck X-rays should also be considered, even if the objects are radiolucent, because they can show indirect signs of a FB, such as air-fluid levels in the esophagus. If patients are symptomatic and the x-rays are negative, endoscopy can be utilized for diagnosis and treatment16,17.

The use of ultrasound in the emergency department has been reported in the detection of a FB in the digestive tract, mainly if the location is esophageal or gastric, but only small case series are described in the current literature18,19.

The authors of an Italian study stated that basic training in point-of-care ultrasound is required for the non-radiologist personnel that work in pediatric emergency services, enabling them to acquire the necessary skills for its implementation. That modality could become a valuable and easily accessible tool for early FB detection in the digestive tract, preventing routine exposure to radiation in those patients20.

Eighty to ninety percent of cases of FBs in the gastrointestinal tract resolve spontaneously with no complications, 10–20% are endoscopically removed, and 1% require surgery secondary to complications21.

The consequences and effects of FBs in the gastrointestinal tract are generally benign, but objects with irregular or sharp surfaces, such as hooks, needles, and chicken or fish bones, can produce severe lesions in the esophagus22. The perforation rate due to sharp objects varies from 15 to 35%. The ingestion of small magnets, commonly used in toys, and the ingestion of batteries require special attention23,24.

Complications can present in an acute manner, related to injury to the mucosa, inflammation, or obstruction, or they can present in a late manner, as scarring, stricture, persistent respiratory symptoms, recurrent pneumonia, weight loss, or delayed growth25,26. There can also be complications secondary to the extraction procedure and the anesthesia administered27.

There is little information on FB ingestion in the Mexican pediatric population. The aim of our study was to describe the clinical, radiographic, and endoscopic characteristics in patients diagnosed with FB ingestion treated at the Instituto Nacional de Pediatría (INP) in Mexico City, as well as the factors associated with the type of object ingested and their anatomic location.

Materials and methodsA descriptive, analytic, cross-sectional study was conducted on patients from 0 to 18 years of age, diagnosed with FB ingestion that were treated at the gastroenterology service of the INP, within the time frame of January 2013 to December 2018. The case records with the following ICD-10 codes corresponding to FB ingestion were accessed: (T18.0) foreign body in mouth, (T18.1) foreign body in esophagus, (T18.2) foreign body in stomach, (T18.3) foreign body in small intestine, (T18.4) foreign body in colon, (T18.5) foreign body in anus and rectum, (T18.8) foreign body in other and multiple parts of the digestive tract, and (T18.9) foreign body of alimentary tract, part unspecified.

The inclusion criteria were patients from 0 to 18 years of age, of either sex, that came to the gastroenterology service of the INP due to FB ingestion, within the study period. The exclusion criteria were patients with a FB at a location other than the gastrointestinal tract, relatives, guardians and/or patients that refused treatment or requested voluntary discharge, and incomplete clinical case files. Thirty-eight patients were excluded from the 123 registers found.

Statistical analysisThe data were registered on a form designed by the lead author and entered into an SPSS® version 22 database for their tabulation and analysis.

Frequencies and percentages were obtained from the qualitative variables of sex, pathologic history, clinical symptoms, imaging findings, FB type and location, endoscopic findings, extraction procedure, and complications.

After carrying out a Kolmogorov–Smirnov normalcy test that showed no normal distribution, medians were obtained from the quantitative variables of age and the time interval from ingestion to hospital arrival, with their respective interquartile ranges and minimum and maximum values.

Intersections between the complications and the type of object ingested, between endoscopic location and type of object, between endoscopic location and object diameter, and between type of object and age under 5 years were carried out. The chi-square test was used to determine associations, and statistical significance was set at a p<0.05. Odds ratios were obtained regarding prevalence, and values above one and their respective 95% CIs, estimating reliable values that did not include the unit, were considered positive associations.

Ethical considerationsNo experiments on animals or humans were conducted. The INP protocols on patient data publication were followed, preserving patient anonymity. Informed consent was not requested because no personal data that could identify the patients appear in the study. The protocol was approved by the academic group of the INP, with number GA/090/19.

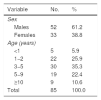

ResultsEighty-five patients were included during the study period, 52 of whom were males (61.2%). Median patient age was 49 months (IQR: 53), with a minimum age of 9 months and a maximum age of 215 months. Table 1 shows the demographic variables.

The majority of patients were between 3 and 5 years of age, with 30 cases (35.3%), followed by those between one and 2 years of age (25.9%).

A total of 3 patients (3.5%) had intellectual development disorder and one patient (1.2%) had a history of gastrointestinal surgery, whereas 81 patients (95.3%) had no underlying disease.

The median time interval from ingestion to hospital arrival was 6h (IQR: 14), with a minimum interval of 0.5h and a maximum interval of 480h, whereas the median time interval from consultation to extraction was 7h (IQR: 13), with a minimum interval of one hour and a maximum interval of 114h.

A total of 57 patients (67.1%) presented with one or more symptoms at the time of evaluation, whereas the remaining patients were asymptomatic. The most common symptom was vomiting, with 25 cases (29.4%), followed by sialorrhea, with 19 cases (22.4%), and dysphagia, with 16 cases (18.8%).

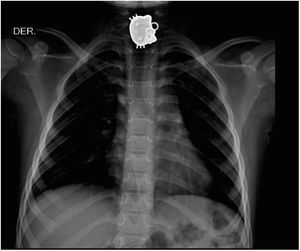

X-rays were carried out on all cases (100%). Sixteen cases (18.8%) had a single projection, 62 patients (72.9%) had two projections, one case (1.1%) had three projections, and 6 cases (7%) had 4 projections, resulting in a total of 167 x-rays and a mean of 2 x-rays per patient. The most frequent projection was the anterior-posterior chest and abdominal projection, carried out in 37 patients (22.2%), followed by the posterior-anterior chest projection, with 31 cases (18.6%).

The objects most commonly ingested were coins (36%), followed by other blunt objects (22%), button cell batteries (18%), sharp objects (11%), food bolus impaction (8%), and magnets (5%) (Fig. 1).

The object could not be visualized through x-ray in 17 cases (20%) but could be visualized in the remaining cases (80%). The most frequent site visualized was the stomach, with 28 cases (32.9%), followed by the upper third of the esophagus, with 20 cases (23.5%), the small bowel in 7 cases (8.2%), the colon in 4 cases (4.7%), the middle esophagus in 3 cases (3.5%), the lower esophagus in 3 cases (3.5%), a supra-esophageal location in 2 cases (2.4%), and an anorectal location in one case (1.2%).

An endoscopic procedure was performed on 76 patients (89.4%) for object extraction, with a total of 74 upper endoscopies, one colonoscopy, and one upper endoscopy-colonoscopy, visualizing the object in 55 of those patients (72.4%).

Of the 17 cases in which the object was not visible through x-ray, visualization was achieved in 10 cases (58.8%) through endoscopy. Of the 20 cases in which the object was radiographically detected in the upper third of the esophagus, 3 (15%) were found in the middle third during upper endoscopy. In the 2 cases whose objects were thought to be located in the small bowel, one (50%) was found in the stomach and the other could not be located endoscopically. The endoscopic location of the 50 remaining objects (90.9%) coincided with the radiographic location.

Of the 76 endoscopies performed, 22 identified erythema (28.9%), 37 erosion (48.6%), 8 ulcer (10.5%), and one identified perforation (1.3%). No necrosis was found in any of the patients (Table 2).

Distribution of the patients with foreign body ingestion, according to the object ingested and the endoscopic finding. Instituto Nacional de Pediatría, Mexico 2013–2018.

| Object | Endoscopic finding | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema/edema | Erosion | Ulcer | Perforation | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Coin | 8 | 25.8 | 20 | 64.5 | 3 | 9.7 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| Other blunt object | 6 | 33.3 | 5 | 27.8 | 3 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Sharp object | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 8 |

| Button cell battery | 5 | 50.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Magnet | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Food bolus impaction | 2 | 28.6 | 2 | 28.6 | 2 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Total | 22 | 37 | 8 | 1 | 76 | ||||

The most common finding in coin ingestion was erosion (64.5%), followed by erythema or edema (25.8%). The most frequent finding in other blunt object ingestion was erythema or edema (33.3%). Strikingly, regarding sharp object ingestion, erosion presented in 25% of cases and perforation in 12.5%. The most common finding in button cell battery ingestion was erosion (60%), followed by erythema/edema (50%), and in relation to magnet ingestion, 100% of the cases presented with erosion and 50% with erythema or edema. Finally, food bolus impaction caused erythema, erosion, and ulcer in equal percentages (28.6%). The ingestion of coins, blunt objects, batteries, or magnets or food bolus impaction did not result in perforation.

The foreign object was extracted through upper endoscopy in 51 patients (60%), purely diagnostic upper endoscopy was performed on 27% of patients, expectant management was decided upon in 10% of patients, extraction was carried out through colonoscopy in one patient (1%), purely diagnostic colonoscopy was performed in one patient, and surgery due to colonic perforation was carried out in one patient.

The most utilized extraction instruments were biopsy forceps (17%) and mouse tooth retrieval forceps (17%), followed by crocodile forceps (15%), basket forceps (9.4%), cold snare (3.8%), and Magill forceps (3.8%). The instruments utilized were not described in the remaining cases (34%).

The primary location of coins was the upper esophagus (48.4%), and other blunt objects were mainly located in the stomach (38.9%). Endoscopically, the majority of sharp objects were not visible (75%), whereas those that were detected, were located in the upper esophagus (12.5%) and colon (12.5%). The majority of button cell batteries were located in the stomach (60%), and magnets had a supra-esophageal location (50%) and gastric location (50%). Finally, the majority of the impacted food was not visible (57%), but in the cases where it could be visualized, the location was supra-esophageal (28.6%) and in the middle esophagus (14.3%) (Table 3).

Distribution of the patients with foreign body ingestion, according to the object ingested and the endoscopic location. Instituto Nacional de Pediatría, Mexico 2013–2018.

| Type of object | Endoscopic location | Total | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not visible | Supra-esophageal | Upper esophagus | Middle esophagus | Lower esophagus | Stomach | Colon | |||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Coin | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 48.4 | 5 | 16.1 | 3 | 9.7 | 6 | 19.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 31 |

| Other blunt object | 6 | 33.3 | 2 | 11.1 | 2 | 11.1 | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 38.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 |

| Sharp object | 6 | 75.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 8 |

| Button cell battery | 3 | 30.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 10 |

| Magnet | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 |

| Food bolus impaction | 4 | 57.1 | 2 | 28.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 |

| Total | 21 | 27.6 | 5 | 6.6 | 18 | 23.7 | 7 | 9.2 | 3 | 3.9 | 20 | 26.3 | 2 | 2.6 | 76 |

In the patients under 5 years of age, most of the FBs were located in the esophagus (52.9%), compared with 47.1% with an extra-esophageal location, with no statistically significant difference (p>0.05). With respect to the type of FB, coins had a 16-fold increased risk for esophageal location (p<0.05) and a diameter≥2cm had a 13-fold increased risk for esophageal location (p<0.05) (Table 4).

Association between esophageal location, age, and type of object and its diameter in patients with foreign body ingestion. Instituto Nacional de Pediatría, Mexico 2013–2018.

| Variable | Esophageal location | OR | 95% CI | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | |||||

| Age<5 years | 18/28 | 52.9 | 16 | 47.1 | 34 | 1.23 | 0.41−3.67 | 0.784 |

| Coin | 23/28 | 79.3 | 6 | 20.7 | 29 | 16.1 | 4.27−60.38 | 0.000a |

| Diameter≥2cm | 24/25 | 68.6 | 11 | 31.4 | 35 | 13.1 | 1.10−122.2 | 0.024a |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Coin ingestion occurred in the majority of children under 5 years of age, compared with those above 5 years of age (80.6 vs 19.4%), resulting in a 3.8-fold increased risk for coin ingestion in children under 5 years of age (p<0.05) (Table 5).

Association between the type of object ingested and age of the patients with foreign body ingestion, according to coin ingestion and patient age. Instituto Nacional de Pediatría, Mexico 2013–2018.

| Age<5 years | Coin | OR | 95% CI | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 80.6 | 28 | 51.9 | 53 | 3.86 | 1.39−10.93 | 0.010a |

| No | 6 | 19.4 | 26 | 48.1 | 32 | |||

| Total | 31 | 100.0 | 54 | 100.0 | 85 | |||

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Finally, the only case of perforation corresponded to the ingestion of a sharp object. Given that there was a total of 8 sharp object ingestions, the perforation rate due to an ingested sharp object was 12.5%. There was no statistically significant difference between sharp object and blunt object ingestion (p>0.05).

Discussion and conclusionsFB ingestion is a frequent cause of emergency pediatric consultation and is one of the primary indications for diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy. However, few studies on the subject have been conducted in developing countries. In our study, we analyzed data collected from patients with FB ingestion that were seen at the gastroenterology service at the INP during the study period, finding 85 patients (61.2% males), similar to reports in the literature describing a predominance of males at a 2:1 male to female ratio28,29. The majority of patients were between 3 and 5 years of age, followed by patients between 1 and 2 years of age, similar to results of other studies reporting patient age from 6 months to 3 years30,31. In our analysis, there was a 3.8-fold higher risk for coin ingestion in patients under 5 years of age (p<0.05).

Despite the fact that the large majority of children that present with FB ingestion are healthy, certain conditions that can be risk factors for complications associated with the detection of ingested objects in the gastrointestinal tract have been described. Among them are swallowing disorders, stricture, motility alterations, achalasia, esophagitis (including eosinophilic esophagitis), adjusted Nissen fundoplication, and congenital defects of the esophagus that have required surgical repair (esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula)32,33. FB ingestion is more frequently seen in children with intellectual development disorder or psychiatric disorder34. In our study, 3 patients presented with intellectual development disorder and one patient had a history of digestive tract surgery as a risk factor for FB retention. The rest of the patients (95.3%) had no underlying disease.

The median time interval from ingestion to hospital arrival was 6h. The initial consultation of many of the patients was at another health institution and they were then referred to our hospital. Other patients had to travel long distances, and in other cases, the parents preferred to wait and begin management at home before going to the hospital. All those were factors that increased the time intervals, but we consider that, in general, the mean time interval for arriving at the hospital was considered early arrival.

According to the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), extraction time can be divided into emergent (<2h from presentation), urgent <24h from the time of ingestion), and elective (>24h post-ingestion)35.

Those times are influenced by the factors of type of FB, FB size and location in the gastrointestinal tract, patient age, and signs and symptoms present during the anamnesis and physical examination, as well as the experience and skill of the endoscopy team36,37.

In our study, the median time between initial consultation and extraction was 7h. Among the parameters that can importantly modify said time interval are opportune radiographic study and the availability of the operating room and the necessary personnel for performing the endoscopic procedure.

Many children that ingest a FB are asymptomatic or can present with nonspecific symptoms38. Commonly observed and described symptoms are sialorrhea (15%), nausea or vomiting (15–30%), dysphagia (23%), and odynophagia39,40. In our analysis, we found similar findings. A total of 67.1% of our patients presented with one or more symptoms at the time of evaluation, whereas the remaining percentage of patients were asymptomatic. The most common symptom was vomiting, with 29.4% of the cases, followed by sialorrhea (22.4%) and dysphagia (18.8%).

Regarding diagnostic imaging, neck, chest, and abdominal x-rays in two projections are described in the literature. X-rays are a diagnostic element that can provide us with direct or indirect signs of the presence of a FB in the digestive tract and possible associated lesions41,42. X-rays were carried out in 100% of our patients and the majority had two projections. The most frequent projection performed was the anterior-posterior chest and abdominal projection (43.5%), which was indicated due to the age of the patient, the majority of whom were under 5 years of age. That projection provided us with radiographic data of the chest, abdomen, and neck. The second most frequent projection was the posterior-anterior chest projection, carried out in 36.5% of the cases.

Coins are the objects most frequently ingested. Other objects, including toys, parts of toys, sharp objects (pins and needles), batteries, chicken bones, and fish bones, are ingested in 5–30% of pediatric FB ingestions43.

In countries such as Japan, where electronic money transactions are more widely used, coin ingestion is less common. The ingestion of plastic objects, and even cigarettes, were the FBs more frequently reported in a Japanese pediatric population44.

Coins were the most commonly ingested FBs (36%) in our study, followed by other blunt objects (22%), button cell batteries (18%), sharp objects (11%), and magnets (5%).

The most common sites of obstruction from an ingested FB include the upper esophageal sphincter, the middle third of the esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter, the pylorus, and the ileocecal valve45. In our study, the most frequent site at which a radiopaque FB was visualized through x-ray was the stomach (32.9%), followed by the upper third of the esophagus (23.5%), the small bowel (8.2%), the colon (4.7%), the middle esophagus (3.5%), the lower esophagus (3.5%), the supra-esophageal region (2.4%), and the anorectal region (1.2%). Coins were mainly located in the upper esophagus (48.4%), similar to reports in the literature describing the region of the upper esophageal sphincter46–48.

Coin ingestion resulted in a 16-fold increased risk for esophageal location (p<0.05) in our patients, and that risk was 13-fold higher with a diameter ≥2cm (p<0.05). The difference in location according to type of object ingested was statistically significant (p<0.05).

If FB ingestion is suspected and there are persistent symptoms, endoscopy should be performed, even if there is a negative radiographic evaluation49.

An endoscopic procedure for FB object extraction was carried out in 89.4% of our study patients. Seventy-four of the procedures were upper endoscopies, one was a colonoscopy, and one was an upper endoscopy-colonoscopy that was performed on a patient that ingested a button cell battery. Its location was difficult to establish through radiography and it was finally extracted from the cecum by colonoscopy. The foreign object was visualized in the endoscopic examination in 55 patients (72.4%). In the cases in which the object could not be detected, a possible explanation could be that the FB had moved in the lapse of time before the endoscopy was carried out.

The objects were not visible by radiography in 20% of the cases, but they were visible in 50% of those cases through endoscopy. Endoscopic location coincided with radiographic location in the majority of cases (90.9%).

The main endoscopic findings were erosion (48.6%), followed by erythema (28.9%), and ulcer (10.5%). There was one case of perforation (1.3%) due to the ingestion of a sharp object that was located in the ascending colon, requiring surgical extraction and repair of the associated injury. The erosion rate for coin ingestion was 64.5%, compared with 37.7% for the ingestion of other types of FBs (p<0.05). Regarding coin ingestion, erosion could be related to the pressure the coin exerts on the surrounding tissues, which in our study was the upper esophagus, as well as to the lapse of time before its removal.

When button cell batteries are lodged in the esophagus, they can cause caustic lesions secondary to the release of hydroxide radicals from leakage of the battery’s content. They can also cause necrosis due to pressure and there can be injury from electrical discharge50,51. The most common finding in our study was erosion (60%), followed by erythema/edema (50%), which could be due to the fact that in the cases of button cell battery ingestion, the batteries were not located in the esophagus, but rather in other parts of the digestive tract — mainly the stomach (60%).

The instruments most used for FB extraction were biopsy forceps (17%) and mouse tooth retrieval forceps (17%). The instrument utilized was not described in 34% of the cases. Importantly, the equipment and material needed for extraction should be at hand. Ideally, it should be tested and in good condition. Before the endoscopy is performed, the instrument’s grasping capacity can be verified with an object similar to the one that is to be removed.

The present study contributes to the local epidemiologic data on the characteristics of pediatric patients presenting with FB ingestion and its associated factors. In the approach to pediatric patients with FB ingestion, numerous factors should be kept in mind, such as the type and size of the foreign body, the lapse of time after object ingestion, the clinical status of the patient, and the age of the patient. Radiography with a minimum of two projections can provide valuable information as to the location and characteristics of the FB. Endoscopy is a very important diagnostic and therapeutic tool in the management of those patients. Preventive measures are needed as a strategic aid in reducing FB ingestion and its possible complications in children.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Navia-López LA, Cadena-León JF, Ignorosa-Arellano KR, Toro-Monjaraz EM, Zárate-Mondragón F, Loredo-Mayer A, et al. Ingesta de cuerpo extraño en pacientes pediátricos en un hospital de tercer nivel y factores asociados. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2022;87:20–28.