Fasciolosis is a zoonosis caused by Fasciola hepatica that affects sheep, cattle, and occasionally, humans. In the latter, 2 phases are distinguished: the acute phase and the chronic phase.1

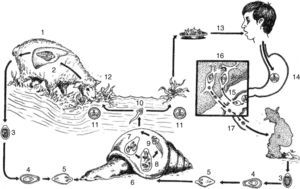

Figure 1 one illustrates the sequential biologic cycle.2

The habitat of adult Fasciola hepatica is in the bile ducts of sheep (1,2). When the eggs are passed into an aquatic environment through feces (3), a ciliated parasite (miracidium) develops inside them (4, 5) that searches for a Lymnaeidae snail (6) and transforms inside it into a sporocyst, mother redia, daughter redia, and cercaria (7, 8, 9). The latter abandons the snail (10) adopting the cystic form of a metacercaria (11) and adheres to different aquatic plants that are eaten by sheep (12). It reaches the duodenum, forming tunnels in the tissue until reaching the liver (1, 2). The acute phase in humans begins when an individual becomes infected by eating watercress (Nasturtium officinale) that contains metacercariae, transforming in the duodenum into adolocercariae (13-15). They penetrate the tissues through proteases until reaching the liver parenchyma, adopting the adult form in a period of 4 to 6 months. The habitat of the adult Fasciola is in the bile ducts, causing the chronic or full-blown disease phase that can last months or years (16,17). (Source: Modified from: Cruz López O.2

Acute phase symptomatology is fever of 38°C, important eosinophilia, abdominal skin rash, and pain in the right hypochondrium. Diagnostic methods in this phase are a complete blood count that shows blood eosinophilia and anti-Fasciola hepatica antibodies. Stool exams in this phase are negative.3

The chronic phase is characterized by adult Fasciola in the biliary tract, causing diarrhea that can be steatorrheic, fever, pain in the right hypochondrium, and weight loss. Eosinophilia can be mild or absent and eggs are found in fecal material.4,5

We present herein the clinical case of a 34-year-old man, resident of Puebla, Mexico, that stated during the medical interview that he had eaten fish with some type of green topping one week before symptom onset, which was characterized by a skin rash on his face, neck and chest, flatulence with borborygmi, and liquid stools with no blood (3 in 24h).

The patient then presented with fever of 38°C, headache, myalgia, pain in the right hypochondrium that radiated to the ipsilateral lumbar region, and weight loss of 4kg in 3 weeks.

The Widal test was negative, but due to the clinical suspicion of typhoid fever, he was given 3g daily of ampicillin for 10 days with no improvement.

Because of the lack of treatment response, the patient sought medical attention at the Clinical Parasitology Service of the Faculty of Medicine of the BUAP. New laboratory tests reported: complete blood count: erythrocytes 4.9mm3, hemoglobin 14.5g/dL, hematocrit 45%, MCV 91 fl, MCHC 32g/dL. Leukocytes 9.15 thousand/μL, with differential count of: lymphocytes 2.19 thousand/μL neutrophils 2.56 thousand/μL, eosinophils 4.11, thousand/μL basophils 0.18 thousand/μL, and monocytes 0.09 thousand/μL.

Because of the high percentage of eosinophils, complete blood count was repeated 8 days later with the following results: erythrocytes 5.0mm3, hemoglobin 14.7g/dL, hematocrit 46%, leukocytes 10.87 thousand/μL, lymphocytes 1.63 thousand/μL, neutrophils 2.82μL, eosinophils 6.19 thousand/μL, basophils 0.0 thousand/μL, and monocytes 0.21 thousand/μL.

The stool exams were performed using the sedimentation technique. Six samples were negative and Enterotest® (Beal Capsule) was negative for cysts, trophozoites, and parasitic eggs.

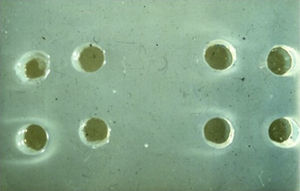

Counterimmunoelectrophoresis (CIE) was carried out to search for anti-Fasciola hepatic antibodies (fig. 2).

The patient was treated with 1mg/kg of weight of intramuscular dehydroemetine for 10 days with total symptom remission.

The present case corresponds to acute (or invasive) phase fasciolosis and is the first of its kind to be reported in Mexico. In Peru, where fasciolosis is endemic, a review carried out from 1963 to 2005 reported a total of 1,701 cases, only 11% of which were diagnosed in the invasive phase and 89% were diagnosed with full-blown disease, corroborating the difficulty of diagnosis in the acute phase.6 As illustrated by the present report, due to its polymorphic symptomatology, physicians do not usually consider this pathology in the differential diagnosis and patients undergo numerous studies and treatments before being correctly diagnosed.7

An important datum is a history of watercress ingestion, which has been identified in national studies in up to 49% of the cases; this history was not obtained or was not reported in 23 and 28% of the cases, respectively. Our patient stated that he was not familiar with watercress, but he did say he had eaten a vegetable topping before clinical symptom onset. Recent reports link fasciolosis with radish ingestion, and to a lesser degree with the ingestion of turnips, spinach, and lettuce, results that require further investigation.8

And finally, our patient was treated with dehydroemetine, due to the nonavailability of the drug that is currently considered the treatment of choice: triclabendazole at an oral dose of 10mg/Kg. Studies have reported the usefulness of nitazoxanide, but the results are still inconclusive.9

We presented this report in the hope it can be useful in the study of patients with eosinophilia and their early treatment.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Manuel Gutiérrez-Quiroz, Head of the Department of Immunoparasitology of the UNAM for providing the antigen used in our study.

Please cite this article as: Cruz y López OR, Gómez de la Vega E, Cárdenas-Perea ME, Gutiérrez-Dávila A, Tamariz-Cruz OJ. Fasciolosis humana diagnosticada en fase aguda. Primer reporte clínico en México. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2016;82:111–113.