Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has revolutionized advanced cancer management. Nevertheless, the generalized use of these medications has led to an increase in the incidence of adverse immune-mediated events and the liver is one of the most frequently affected organs.

Liver involvement associated with the administration of immunotherapy is known as immune-mediated hepatitis (IMH), whose incidence and clinical characteristics have been described by different authors. It often presents as mild elevations of amino transferase levels, seen in routine blood tests, that spontaneously return to normal, but it can also manifest as severe transaminitis, possibly leading to the permanent discontinuation of treatment.

The aim of the following review was to describe the most up-to-date concepts regarding the epidemiology, diagnosis, risk factors, and progression of IMH, as well as its incidence in different types of common cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma. Treatment recommendations according to the most current guidelines are also provided.

La inmunoterapia con inhibidores de puntos de control inmunitario (ICP) ha revolucionado el manejo del cáncer avanzado, sin embargo, el uso generalizado de estos medicamentos ha llevado al aumento en la incidencia de eventos adversos inmunomediados, siendo el hígado uno de los órganos más frecuentemente afectados.

La afectación hepática asociada con la administración de inmunoterapia se denomina hepatitis inmunomediada (HIM), cuya incidencia y características clínicas han sido descritas por distintos autores, frecuentemente se manifiesta como elevaciones leves en las aminotransferasas evidenciadas en la analítica de rutina que regresan a la normalidad de forma espontánea, aunque puede tratarse de una transaminasemia grave que lleve a la suspensión definitiva del tratamiento.

El objetivo de la siguiente revisión fue describir los conceptos más actuales sobre la epidemiología, diagnóstico, factores de riesgo y evolución de la HIM, así como la incidencia de ésta en los diferentes tipos de cáncer más frecuentes incluyendo el carcinoma hepatocelular y algunas recomendaciones respecto al tratamiento de acuerdo con las guías más actuales.

In recent years, immunotherapy has revolutionized oncologic treatment. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are monoclonal antibodies that block the downregulators of the immune response, reinforcing the anti-cancer immunity of the host. This activation of the immune system leads to the development of diverse inflammatory adverse events and the liver is one of the most frequently affected organs.1 Liver injury secondary to the administration of immunotherapy is known as immune-mediated hepatitis (IMH). It presents in approximately 15% of patients1–7 and is characterized by elevated aminotransferase levels that appear in routine blood tests, usually at the third cycle of treatment.8,9 The spectrum of IMH varies from mild elevations of aminotransferases that spontaneously return to normal, to elevations of aminotransferases that are 20-times the upper limit of normal (ULN) and are life-threatening. Management of patients with IMH is based on severity, even requiring treatment suspension in severe cases. With the recent approval of new oncologic treatments, an increase in cases of IMH is expected, resulting in the need to establish adequate treatment guidelines, utilizing severity scales that more accurately evaluate liver function. This is especially true for patients with an underlying liver disease, in whom the current severity evaluation scale could overestimate liver injury severity. Our aim is to describe the most up-to-date concepts on the epidemiology, diagnosis, risk factors, and progression of IMH, as well as its incidence in the different most common types of cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We also provide herein treatment recommendations, according to the most current guidelines.

The concept of immunotherapy in cancerCancer is considered a disease of the genome. The main mechanisms involved in cell division and DNA replication are susceptible to errors that can compromise genetic integrity, resulting in the development of neoplastic cells.10,11 There are intrinsic and extrinsic tumor suppression mechanisms whose purpose is to recognize and eliminate malignant cells.12 Innate and adaptive immune system cells have the capacity to eliminate neoplastic cells upon infiltrating themselves into the tumor microenvironment (TME) and identifying the tumor cells by recognizing tumor-associated antigens (TAAs).12–14 The goal of immunotherapy is to strengthen the immune response mechanisms and thus eliminate the malignant cells.14 The ICIs are monoclonal antibodies that increase anti-cancer immunity by blocking downregulators of the immune response, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), which leads to the improvement in T-cell function and recovery of anti-tumor activity of the host.1

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) was the first immune checkpoint to be identified.15 It is expressed mainly in T cells and its CD80 and CD86 ligands are found on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), having an affinity for the two homologous proteins (CD28 and CTLA-4). Depending on the receptor, the interaction of those ligands results in a costimulatory or coinhibitory response (dependent on CD28 and CTLA-4, respectively).16,17 Upon binding to its ligands, CTLA-4 phosphorylates to activate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, which leads to two canonic events: 1) the dephosphorylation of the CD3ζ chain, limiting the signaling of the T-cell receptor (TCR) and 2) the inhibition of the IL-2 transcription pathway, which reduces T-lymphocyte differentiation and activation.18–20

Programmed cell death protein 1 and programmed cell death ligand 1PD-1 is mainly expressed in activated T cells by the TCR pathway and the stimulation of cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21.21,22 The binding of PD-1 with its ligands in the APCs triggers an anergic response with deficient production of proinflammatory cytokines, as well as lower survival of immune cells, through the decrease in the transcription of cell survival proteins, such as Bcl-XL.21 The interaction of PD-1 and PD-L1 is one of the most important mechanisms of tumor immune evasion.13,23 Due to the activation of the immune system, ICIs can produce a wide variety of inflammatory side effects, called immune-related adverse events (irAEs), that can affect almost any organ, especially the skin, liver, endocrine system, and gastrointestinal tract.24,25

Immune-mediated hepatitisConceptThe liver is one of the organs most frequently affected by immunotherapy for cancer, most likely as a consequence of its particular immune microenvironment. Liver injury caused by treatment with ICIs is called “immune-mediated liver injury caused by ICIs (ILICI) or immune-mediated hepatitis (IMH).1 It is a unique type of drug-induced liver injury (DILI),24 different from direct DILI or idiosyncratic DILI, and is secondary to the action of the drug on the immune system.9 The pathogenesis of IMH appears to have a multifactorial origin. In general, the immune activation induced by the ICI leads to, not only a T-cell-mediated anti-tumor response, but also to a loss of peripheral tolerance to the patient’s own cells.26 T cells activated as a consequence of ICI administration have been proposed to be sequestered by the liver through the binding of α4β1-integrin and LFA-1, expressed by activated CD8 + T cells, with the adhesion molecules, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, respectively (expressed in hepatic sinusoids by endothelial cells and Kupffer cells). In the hepatic sinusoid, activated T cells induce TNF-α expression and secretion by Kupffer cells, through the activation of Fas by the Fas ligand and the secretion of IFN-gamma. This increase in TNF-α secretion induces hepatocyte apoptosis, mediated by Fas and IFN-gamma.27

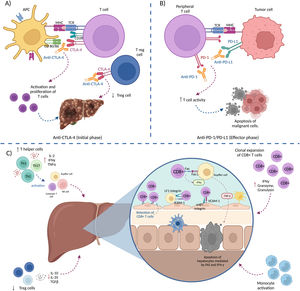

Fig. 1 describes the pathophysiologic events associated with the development of IMH.1,27–29 IMH more frequently presents as hepatocellular damage, with elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST), with or without elevated bilirubin levels,8 albeit it can present as cholestatic or mixed damage in some patients.24 It tends to appear between 6 and 14 weeks after the start of treatment with ICIs, which usually corresponds to one to 3 cycles of treatment.8,9 The sequence of events shown in Fig. 1 are:

- A)

Initial phase: the blockage of CTLA-4 (expressed in T cells and regulatory T cells [Tregs]) counterbalances the inhibition of the immune response, leading to T-cell activation and proliferation and reducing the number of Tregs in the TME.

- B)

The binding of PD-1 (expressed in peripheral T cells) to PD-L1 (expressed by tumor cells and immune cells) downregulates T-cell activity (immune evasion), thus the blockade of said binding, using anti-PD1/PD-L1 antibodies, increases T-cell activity, destroying the tumor cells.

- C)

Mechanisms that contribute to the development of IMH: 1) expansion of cooperative T cells (Th1 and Th17), 2) decrease in Tregs, 3) activation of monocytes, 4) clonal expansion of CD8 + T cells, and 5) retention of activated CD8 + T cells in the liver. The retention of CD8 + T cells leads to IFN-gamma secretion by CD8 + T cells, mediated by Fas/FasL interaction that induces TNF-α secretion by Kupffer cells, resulting in hepatocyte apoptosis.

Mild elevations in ALT or AST levels can be transitory and spontaneously return to normal, despite continuing treatment. This phenomenon is called “adaptation”, which is why the majority of cases of mildly elevated transaminases (ALT > 1-3 times the ULN), with no symptoms or elevated total bilirubin, are not clinically significant cases of IMH, and more adequately, are described as “elevations in serum transaminases”.24

According to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the Toxicity Management Working Group of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC), and the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), IMH is classified into 4 grades, depending on the level of elevation of transaminases and total bilirubin (Table 1).8,30,31 This severity scale has traditionally been used in oncology clinical trials, and so is universally accepted as useful. However, it is far from being an accurate scale determining the severity of a hepatic inflammatory process. First of all, it does not take into account prothrombin time or the INR in evaluating the severity of IMH, parameters which are essential in assessing liver function and key to treatment decision-making, as described in this section. Secondly, it separates the elevation of bilirubin from the elevation of transaminases in grade 4 (according to its scale). This fact overestimates transaminase elevation as a severity marker of the clinical picture, given that isolated transaminase elevation does not translate into liver dysfunction. Therefore, among other reasons that we will develop in this article further ahead, the CTCAE should probably not be the cornerstone upon which the treatment of these patients is based.

Stratification of IMH.

| Grade | Transaminases | Bilirubin |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Mild | ALT or AST 1-× the ULN | Total bilirubin > 1 - 1.5× the ULN |

| 2 Moderate | ALT or AST > 3 - ≤ 5× the ULN | Total bilirubin >1.5 - ≤3× the ULN |

| 3 Severe | ALT or AST > 5-20× the ULN | Total bilirubin >3× the ULN |

| 4 Life-threatening | ALT or AST > 20× the ULN |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; IMH: immune-mediated hepatitis; ULN: upper limit of normal.

IMH is the third most frequent irAE, after dermatologic toxicity (44-68%) and gastrointestinal toxicity (35-50%).32 It presents in 3-16% of patients during monotherapy treatment with ICIs,2–7 whereas the incidence of grade 3 transaminase elevation (ALT or AST), or higher, varies from 0 to 6% with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy2,6,7 and can increase to 12% with anti-CTLA-4 therapy.5 The CTLA-4 inhibitors (ipilimumab and tremelimumab) have the highest liver toxicity rates, whereas monotherapy with anti-PD-1 antibodies (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) has the lowest incidence of IMH.26,33 The incidence of elevated aminotransferases (ALT or AST) has been reported to be higher in patients receiving combination therapy (anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 + anti-CTLA-4), with incidences that vary from 9 to 17%,4,7,34 but in some case series on combination treatment in patients with non-hepatocellular tumors, incidences of up to 37% have been reported.35 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis described an incidence of 12% for any grade of transaminase elevation and an incidence of 3.5% for grade 3 or higher transaminase elevation, in patients with combination immunotherapy.36 Severe acute liver injury and death are rare, with an incidence of 0.4%, particularly with CTLA-4 inhibitors.37

Natural historyThe clinical spectrum of IMH varies from mildly elevated aminotransferases, in which the patient is clinically asymptomatic, to severe acute liver injury.24 The most frequent clinical presentation is asymptomatic hepatitis (46%),38 with elevated transaminases observed in routine blood tests performed before each treatment cycle.26 It tends to present between week 6-14 after the start of treatment with ICIs, which usually corresponds to 1-3 treatment cycles.8,9 In a recent retrospective study that included 164 patients, the mean time to hepatitis diagnosis was 61 days.38 A considerable percentage of patients can present with fever/anorexia (17.1%), nausea/vomiting (14%), general malaise, lumbosacral or right upper quadrant abdominal pain (11.6%), jaundice, choluria, anorexia, the appearance of small impact hematomas, or myalgia/arthralgia.26,38 Laboratory test parameters, such as total bilirubin, prothrombin time, and V-factor, provide prognostic information.30 IMH usually resolves within 4-6 weeks with adequate treatment.30 In a retrospective study conducted at 6 international institutions and on 169 patients, 30% of the patients had grade 2 IMH and 45% had grade 3, with a mean time of 13 days for attaining one grade of improvement and 52 days for attaining complete resolution. The majority of those patients were treated with glucocorticoids (92%); almost one-fourth of the patients (23%) required second-line immunosuppression; 5 patients died due to complications from hepatitis or from the treatment itself; and treatment could not be re-established in over half of the patients (58.6%).37,38

Immune-mediated hepatitis in non-hepatocellular carcinoma solid tumorsMelanomaImmunotherapy is the standard treatment for stage III and IV nonresectable melanoma. First-line treatment includes the administration of an anti-PD-1 antibody (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) as monotherapy or the combination of anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4 antibodies (nivolumab + ipilimumab); in patients with the BRAF-V600 mutation, BRAF inhibition (vemurafenib, dabrafenib, or encorafenib) is indicated, in combination with an MEK inhibitor (cobimetinib, trametinib, or binimetinib).39 Until a few years ago, ipilimumab monotherapy had been considered standard treatment for advanced melanoma. The incidence of any grade of altered liver enzymes, in the treatment of metastatic melanoma with ipilimumab monotherapy, at a dose of 3 mg/kg, is 3.8%,40 whereas it increases to 16% when the dose is 10 mg/kg, mainly in grades 3 and 4 (37 and 50%, respectively).5 The frequency of elevated aminotransferases (ALT or AST) with nivolumab monotherapy is 3.8% and increases to 15 to 17% when administered in combination with ipilimumab.34 The reported frequency of IMH in the treatment with pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg every 3 weeks) is 1.8%.41

Lung cancerLung cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide and the most frequent cause of cancer deaths.42 Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common subtype (85%).43 The treatment focus of NSCLC depends on tumor stage and histology, genetic alterations, and conditions of the patient; around 30% of patients will have locally advanced disease (T3-T4, N2-N3, stage IIIA-C).44 In patients with advanced disease and no genetic alterations that can receive targeted therapy (EGFR, ALK, RET, BRAF, ROS1, NTRK, MET, and KRAS), standard treatment is the combination of chemoimmunotherapy with an anti-PD-1 (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) or anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab) as monotherapy or in combination with an anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab/nivolumab).43 The incidence of any grade of altered aminotransferases (ALT or AST) with the administration of pembrolizumab for the treatment of advanced NSCLC varies from 6 to 7%, whereas the incidence of grade 3 hypertransaminasemia, or higher, is 1%,45 and IMH criteria are met in only 0.6 to 1% of cases.46 In contrast, up to 10% of patients treated with atezolizumab, in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel, present with hepatitis.47 The incidence of IMH with combination therapy has been reported at up to 6%, with the administration of nivolumab/ipilimumab. The mean onset time is 3.6 months and 75% of cases have disease resolution.48

Colorectal cancerColorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer worldwide.42 Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) is the first-line treatment for metastatic CRC with the so-called mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high (dMMR/MSI-H) disease.49,50 This group of patients accounts for 15% of all cases of CRC.51

In the recent phase III KEYNOTE-177 study (pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy), pembrolizumab administration in patients with dMMR/MSI-H metastatic CRC showed improvement in progression-free survival. The incidence of elevated AST (any grade) was 10% and was grade 3 in only 1% of the cases, whereas up to 3% of the patients presented with IMH.52 The nivolumab/ipilimumab dual blockade has also shown clinical benefit in that group of patients, with a greater incidence of hepatic adverse events (15% for any grade and 4% for grades 3 and 4) at a mean onset of 6.4 weeks.53

Immune-mediated hepatitis in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinomaHCC is the seventh most common cancer worldwide42,54 and the third most frequent cause of cancer deaths.55 Approximately 60% of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages.56 With the advent of new systemic therapies, survival in patients in advanced stages has improved significantly.55

The inhibition of angiogenesis is an important component of HCC treatment. The drugs that inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) include tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as sorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib, or regorafenib, and antibodies, such as bevacizumab and ramucirumab.57 TKIs have been shown to be associated with an increased risk for elevated ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and bilirubin, of any grade (RR that varies from 1.2 to 1.57), and with grade 3 or 4 elevated ALT and AST (RR 1.61-1.66).58 Sorafenib was the first targeted therapy to show efficacy in patients with advanced HCC.59 After sorafenib, different agents have been approved as first-line treatment (lenvatinib) and second-line treatment (cabozantinib, regorafenib, ramucirumab, and pembrolizumab).60

Altered liver function tests are frequent in the systemic treatment of HCC. The incidence of any grade of elevated aminotransferases (ALT or AST) with sorafenib administration for the treatment of advanced HCC has been reported from 5 to 17% and from 2 to 8% for grades 3 or 4.7,61–63 In addition, the reported incidence of elevated bilirubin is from 7.8 to 14%.7,61,63 The frequency of elevated AST, with the administration of lenvatinib, is similar to that of sorafenib, with elevation of any grade of 14%, and 5% for grade 3 or higher.63 Currently, the atezolizumab/bevacizumab (anti-PD-L1/VEGF inhibitor) and durvalumab/tremelimumab (anti-PD-L1/anti-CTLA-4) combinations are first-line treatment for advanced HCC (stage: BCLC-C).64 Both treatments have been shown to significantly improve survival, compared with sorafenib,7,61 and this is also the case with atezolizumab/bevacizumab, with respect to progression-free survival and treatment response rate.61 Up to 20% of patients treated with atezolizumab/bevacizumab present with any grade of elevated aminotransferases (ALT or AST), whereas only 4% present with grade 3 elevated AST, or higher.61,65 The incidence of elevated transaminases (ALT or AST), with the administration of durvalumab/tremelimumab, is from 9.3 to 12.4%, for any grade of transaminasemia, and from 2.6 to 5.2%, for grade 3 or 4 elevated transaminases.7Table 2 summarizes the incidence of elevated aminotransferases with the different treatments utilized in HCC and other solid tumors.66–69

Incidence of aminotransferase elevation in oncologic treatment.

| Type | Group | Drug | Indication (1) | Hypertransaminasemia (ALT or AST) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF inhibitors | TKIs | Sorafenib | HCC | 5% - 17% (7,61–63) |

| Lenvatinib | HCC | 14% (63) | ||

| Cabozantinib | HCC | 29% - 33% (62) | ||

| Regorafenib | HCC | 8% - 13% (66) | ||

| Antibodies | Bevacizumab | HCC | 38% (67) | |

| Ramucirumab | HCC | 51% (68) | ||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | Anti-PD-1 antibody | Nivolumab | Melanoma, NSCLC, ECG, RCC, CRC, HL | 3.8% - 12% (4,34) |

| Pembrolizumab | Melanoma, NSCLC, CRC, HL, EGC, HCC, Endometrial or cervical cancer | 1.8% - 7% (41,45) | ||

| Anti-PD-L1 antibody | Atezolizumab | HCC, NSCLC, Melanoma, Urothelial cancer | 13% (65) | |

| Durvalumab | HCC, NSCLC | 11.3% - 14.4%(7) | ||

| Anti-CTLA-4 antibody | Ipilimumab | Melanoma, RCC, CRC, HCC, NSCLC, EGC | 3.8% (3 mg/kg dose) (40) | |

| 16% (10 mg/kg dose) (5) | ||||

| Tremelimumab | HCC | 55 - 70%(69) | ||

| Combinations | Ipilimumab + Nivolumab | Melanoma, NSCLC, CRC, EGC | 6% - 17% (4,34,48) | |

| Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | HCC | 14% - 20% (61,65) | ||

| Durvalumab + Tremelimumab | HCC | 9.3% - 12.4%(7) |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CRC: colorectal cancer; EGC: esophagogastric cancer; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; HL: Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; RCC: renal cell carcinoma; TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

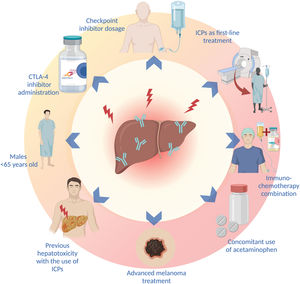

Sex, age, type and dose of ICI, combination treatments, the concomitant use of other drugs, and the type of malignancy are factors that increase the risk for presenting with ICI treatment-associated liver toxicity. IMH has been reported to be more frequent in women (p = 0.038),70 but other studies have found a higher incidence of liver toxicity in men under 65 years of age.71 In fact, patients < 65 years of age appear to have 5-times more risk of IMH, compared with patients above 70 years of age, which is most likely associated with the immunosenescence that characterizes older patients.71 On the other hand, patients with pre-existing immune diseases have not been shown to have a higher frequency of IMH, compared with the general population.72

A higher incidence of IMH has been described, with the administration of CTLA-4 inhibitors (ipilimumab and tremelimumab).26 In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, CTLA-4 inhibitors were shown to be associated with a greater risk for liver toxicity, of any grade (OR: 1.24, 95% CI: 0.75-2.05, p = 0.39), and grade 3 liver toxicity, or higher (OR: 1.93, 95% CI: 0.84-4.44; p = 0.12).33 Likewise, the use of PD-1 inhibitors has been associated with a higher incidence of grade 3 irAEs, or higher, compared with PD-L1 inhibition (OR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.00-2.54).2 In addition to the type of ICI, the risk of IMH is correlated with medication dose; the incidence of irAEs has been shown to be greater with higher doses of ipilimumab.5,40 Patients treated with combinations of ICIs and those that receive ICIs as first-line treatment also present with a higher risk for IMH (p < 0.001 and p = 0.018, respectively.70

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the immunotherapy-chemotherapy combination produced a higher incidence of irAEs than the combinations of anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1 with VEGF inhibitors, and the combinations of ICIs (anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1 with anti-CTLA-4). Up to 25% of patients treated with chemotherapy-immunotherapy combinations presented with elevated aminotransferases (of any grade), but only 2-4% were grade 3 or higher.36 In addition to combination treatment, the use of drugs, such as acetaminophen, has been associated with a 2-times greater risk for liver toxicity.71

The type of malignancy appears to have an impact on the risk for developing IMH. A higher probability of developing liver toxicity in the treatment of advanced melanoma, compared with other types of cancer (OR: 5.66, 95% CI: 4.39-7.29, p < 0.00001 vs. OR: 2.71, 95% CI: 2.04-3.29, p < 0.00001), has been reported.33 The presence of an underlying liver disease or HCC has not been shown to confer a higher risk for developing IMH,26,73,74 but an increase in the risk for developing ascites and encephalopathy in patients with Child-Pugh B ≥ 7 points has been demonstrated.74

The risk for presenting with an irAE is higher in patients that have previously presented with irAEs, but that does not predict the appearance of the same irAE, upon changing the type of ICI.26,72 The recurrence rate of the same irAE, associated with the discontinuation of treatment after restarting the same ICI, is 28.8%, and so starting the same treatment can be considered in selected patients, with adequate monitoring.75 The most frequent risk factors for developing liver toxicity are listed in Fig. 2.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosisThe liver panel is the first-line test for diagnosing IMH. All patients treated with ICIs should be routinely evaluated to detect the development of hepatitis, through determining serum transaminases, ALP, and bilirubin levels, before each treatment cycle.30 Nonspecific findings, such as mild hepatomegaly, edema, and periportal lymphadenopathy, can be found in imaging studies (computed tomography) of patients with markedly elevated transaminases (ALT > 1000 IU/l).76 Due to the lack of specific markers, the rule-out diagnosis is crucial. Other causes of liver damage, such as hepatotoxic medications, alcohol use, viral hepatitis, metabolic diseases, vascular disease, and tumor progression, should be ruled out. 8,30,77

Specific tests include serology tests for hepatotropic (hepatitis A, B, C, and E) and non-hepatotropic (Epstein-Barr, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex) viruses and imaging studies to evaluate the biliary tree and hepatic vasculature, such as liver ultrasound or computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging in cases of elevated ALP and/or bilirubin. Computed tomography can be useful in the evaluation of tumor progression (liver metastases).78

Even though the majority of the guidelines recommend liver biopsy, it is currently not recommended as a standard care strategy due to its nonspecific findings. However, it could be useful in the differential diagnosis of severe hepatitis.8,30

In patients with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment, the most frequent histologic finding is lobular hepatitis, with inflammatory infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and only a few plasma cells. More than half of the patients can have bile duct injury, with lymphocytic cholangitis or ductal dystrophy.79 Confluent necrosis is rare in anti-PD-1 (nivolumab)-induced hepatitis.80 On the other hand, granulomatous hepatitis associated with inflammatory lobular activity (panlobular and in zone 3) that is necrotic, including fibrin ring granulomas and central vein endotheliosis, is more frequently observed in liver biopsy in patients with anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab)-induced hepatitis.76,79,81

IMH shares some histologic characteristics with DILI and autoimmune hepatitis, such as lobular damage and portal inflammation. Nevertheless, in ICI-induced hepatitis, confluent hepatitis is rare, compared with autoimmune hepatitis and DILI. In addition, the plasmacytosis characteristic of autoimmune hepatitis and eosinophilic infiltration or the bile plugs seen in DILI are less prominent in IMH.

Immune staining in patients with hepatitis due to ICIs can show the presence of a large quantity of CD3+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, whereas the quantity of CD20 + B cells and CD4 + T cells is lower, compared with autoimmune hepatitis or DILI.80

TreatmentGeneral concepts in the treatment of immune-mediated hepatitisThe management of patients with IMH is based on severity, and severity is usually evaluated according to the CTCAE. But given the lack of accuracy in the current guidelines, with respect to assessing severity, as mentioned above, the use of Hy’s law is more appropriate in the diagnosis of severe IMH. Hy’s law has been shown to be a tool with high sensitivity and specificity in predicting drug-mediated liver toxicity. This law consists of 3 components: a) a greater incidence of liver dysfunction in patients with ALT or AST 3 or more-times higher than the ULN in patients treated with drugs that are potentially hepatotoxic, compared with patients treated with non-hepatotoxic drugs or placebo; b) patients whose ALT or AST is 3-times higher than the ULN, together with total bilirubin > 2 times the ULN, with no signs of cholestasis (defined by elevated ALP); and c) absence of any alternative cause that could explain the combination of increased ALT or AST and total bilirubin. The presence of these elements indicates a potentially very severe hepatocellular lesion, associated with an incidence of death/need for liver transplantation, of about 10%.82 With that in mind, it is probably more adequate to use the severity criteria of the US Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network83 or those of the International DILI Expert Working Group,84 given that they are much more appropriate for evaluating the severity of liver injury (Table 3).

IMH severity criteria.

| US Drug-induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) | |

|---|---|

| 1 Mild | Elevated ALT and/or ALP but total bilirubin < 2.5 mg/dL and INR < 1.5 |

| 2 Moderate | Elevated ALT and/or ALP and total bilirubin ≥ 2.5 mg/dL or INR ≥ 1.5 |

| 3 Moderate/severe | Elevated ALT, ALP, total bilirubin and/or INR and need for hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization as a consequence of DILI |

| 4 Severe | Elevated ALT and/or ALP and total bilirubin ≥ 2.5 mg/dL and at least one of the following: |

| - Liver failure (INR ≥ 1.5, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy) | |

| - Organ failure secondary to DILI | |

| 5 Fatal | Death or transplant secondary to DILI |

| International DILI Expert Working Group | |

| 1 Mild | ALT ≥ 5 × ULN or ALP ≥ 2 × ULN and total bilirubin < 2 × ULN |

| 2 Moderate | ALT ≥ 5 × ULN or ALP ≥ 2 × ULN and total bilirubin < 2 × ULN or symptomatic hepatitis |

| Severe | ALT ≥ 5 × ULN or ALP ≥ 2 × ULN and total bilirubin ≥ 2 × ULN or symptomatic hepatitis and at least one of the following criteria: |

| - INR ≥ 1.5 | |

| - Ascites and/or hepatic encephalopathy, duration < 26 weeks and absence of cirrhosis | |

| - Organ failure secondary to DILI | |

| 4 Fatal/transplantation | Death or liver transplantation secondary to DILI |

ALT: alanine transferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; DILI: drug-induced liver injury; IMH: immune-mediated hepatitis; INR: international normalized ratio; ULN: upper limit of normal.

Treatment in patients with solid tumors other than hepatocellular carcinoma

As previously described, the CTCAE scale (Table 1) lacks sufficient accuracy to adequately evaluate severity. Nevertheless, given its widespread use, treatment recommendations are generally based on those criteria.

The patients that present with grade 1 IMH do not require a specific treatment, nor the suspension of oncologic treatment.77 They can be managed ambulatorily, through control blood tests every fifteen days.78,85 Even though there is a broad consensus regarding grade 1 IMH, recommendations for grade 2 IMH vary substantially between groups and clinical guidelines, basically due to the scarcity of scientific evidence. On the one hand, some groups propose carrying out clinical laboratory test control periodically (every 3 to 5 days), without starting immunosuppressive treatment, or they suggest considering the use of prednisone (0.5-1 mg/kg/day),35,77,85 whereas others recommend starting treatment as soon as possible.78,86 Despite these differences, current evidence –albeit still scarce– indicates that these patients have good clinical progression, without starting immunosuppressive therapy.35,87

Considering this variability, the importance of a correct evaluation of the liver situation, beyond that which can be made with the CTCAE scale, comes into play here. In fact, strict biochemical control could be recommended in patients that present with grade 2 IMH and no liver dysfunction. This clinical and laboratory test control should be carried out periodically on a weekly basis, starting immunosuppressive treatment in patients presenting with a decline in liver function during follow-up.

The management of patients with grade 3 IMH, or higher, is complex. Currently, the oncology clinical guidelines and action protocols included in the vast majority of clinical trials invariably indicate starting immunosuppressive therapy in all patients with grade 3 or higher. Importantly, grade 3 IMH does not imply liver dysfunction, which would be considered when a patient presents with transaminases of about 200 IU/l (5-times higher than the ULN, assuming the limit is 40 IU/l; this value can vary, depending on the laboratory), even though there is no liver dysfunction. These transaminase values reflect liver necroinflammation, but not necessarily a medical emergency. In fact, such values are not infrequent in daily hepatology consultation, and in many cases, do not require urgent therapeutic management. Because of this situation, as well as the rigidity of the recommendations made in clinical trials, patients were invariably treated, resulting in insufficient information on the progression of untreated patients, but this has changed in recent years. In a retrospective study published in 2020, the progression of patients with grade 3 and grade 4 IMH, that were untreated, was found to be similar to that of the treated patients.88 Of the 100 patients included in the analysis, 85 had grade 3 and 15 had grade 4. Sixty-seven patients were treated with corticotherapy and the remaining 33 were not. No differences in the clinical, therapeutic, or demographic characteristics were found. The only statistically significant difference was that recovery, understood as reaching an ALT value ≤ grade 1, was achieved sooner in the patients that did not receive treatment, than in the patients treated with corticoids. Given these and other data, temporarily suspending oncologic treatment, not starting immunosuppressive therapy, and carrying out periodic control tests every 48-72 h, in patients in good general condition that have no organ involvement or liver dysfunction, appears to be reasonable.35,77,85,89

Immunosuppressive treatment should be started in patients that have an INR > 1.5, bilirubin ≥ 2.5 mg/dl, and present with progressive biochemical parameter deterioration or do not present with clear improvement after 7 days of monitoring.

Corticotherapy is the cornerstone of IMH treatment. Recommended doses vary from 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day. Despite the fact that different consensuses and management guidelines occasionally recommend doses up to 2 mg/kg/day (in grade 4 IMH),77 there is no evidence that very high doses are efficacious. In this regard, a small British study that included 21 patients found that doses above 60 mg every 24 h offered no advantages over lower doses, and exposed the patients with high doses to a greater risk for adverse effects.90 In addition, a recent study on a large multicenter cohort of patients that included 215 cases of grade 3 IMH, or higher, found that the patients that received high doses of corticoids (>1.5 mg/kg/day) did not have better clinical progression or faster recovery, but had a higher risk for developing infectious complications and steroid-induced diabetes, as well.91 After starting treatment, progressive drug withdrawal can be begun when there is improvement in laboratory test results. Even though there is no clear consensus on how corticoids should be withdrawn, progressive withdrawal of 10 mg weekly until suspension is recommended and should be carried out during the first 4 to 8 weeks.85

Treatment in patients with hepatocellular carcinomaThe majority of patients with HCC have underlying cirrhosis, a relevant fact regarding the grading of severity, and possibly management. Many of these patients present with elevated baseline transaminase values, which is why the strict application of the CTCAE scale –the limitations of which have been widely described herein– can overestimate severity, and as a consequence, negatively impact clinical management.

Treatment choice and dosage are similar to those in patients with solid tumors other than HCC. Nevertheless, even though there is still insufficient evidence on the subject, starting treatment –and consequently, not monitoring the patient– appears to be reasonable in patients that present with grade 3 IMH, or higher, given that their baseline liver function reserve is limited due to the underlying liver disease, and so they most likely have a greater risk for decompensation.

Conventional treatment-refractory patientsThere is no consensus on the definition of lack of response to treatment. In general, IMH is considered refractory when there is no improvement in laboratory test results, or they worsen despite adequate steroid treatment. The time lapse needed for lack of response to be considered is not clearly defined, and usually varies from 378 to 785 days from the start of corticoid treatment. Even though there are no tools for predicting first-line treatment failure, the presence of underlying liver disease or hyperbilirubinemia, at the time of IMH diagnosis, appears to be associated with a greater risk for refractoriness to steroid treatment.92 Oncologic treatment does not appear to have an impact on the risk for therapeutic failure.

The most widely studied drug with more evidence on its use as second-line treatment is mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). MMF is a prodrug of mycophenolic acid, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase. This enzyme is necessary for purine production during proliferation and is especially important in lymphocytes. The dose usually utilized is the same one used in autoimmune hepatitis, i.e., 1 g every 12 h. A recent study showed that the addition of MMF to steroid treatment is capable of inducing response in more than 80% of patients with steroid-refractory hepatitis (absence of clinical and biologic response at a systemic steroid dose ≥ 1 mg/kg/day).92 The most recent recommendations suggest starting MMF in patients with severe hepatitis that persists despite 3 days of treatment with steroids.77 The severe treatment adverse effect of myelosuppression must be kept in mind, and so strict laboratory control testing should be carried out.

An alternative to MMF is tacrolimus. Its immunosuppressive effect is a consequence of calcineurin inhibition, and it exerts said effect on T and B cells. The little evidence there is comes mainly from clinical cases or case series. The plasma concentration of the drug should be titrated, to prevent severe adverse effects, especially of nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity. In addition, there is no consensus on the target plasma levels to be reached, for enhancing its immunosuppressive effect, while at the same time minimizing toxicity. Therefore, in general, utilizing the same limits used in autoimmune hepatitis is suggested.

Other therapeutic alternatives have been evaluated in cases that are refractory to the customary second-line treatments or that rapidly progress to severe acute liver failure, recognizing the fact that said patients are usually not candidates for liver transplantation because they have a disseminated oncologic disease. Antithymocyte globulin stands out among those alternatives. It is a treatment that showed efficacy in a recently published clinical case series. Despite the fact that there is no established therapeutic structure, the patients were treated with two cycles of thymoglobulin at 1.5 mg/kg.93,94 Another potential alternative is plasma exchange, in which 5 separate exchange sessions are performed, with a 48 h interval between each one.95 Nevertheless, a generalized therapeutic recommendation cannot be made because there is a lack of solid information in this area. Thus, the implementation of these treatment alternatives should be considered with caution and evaluated individually.

Retreatment in patients with previous immune-mediated hepatitisContrary to the classic concept, the recurrence of IMH in patients that are retreated with immunotherapy is rare. In fact, reports have stated that only around 29% of patients develop a new episode of any grade of IMH after the reintroduction of immunotherapy.75 Anti-CTLA-4-based regimens in immunotherapy appear to be associated with a greater risk for relapse, but their combination with anti-PD1/anti-PDL1 antibodies is not associated with a higher recurrence, and apparently, neither is anti-PD1/anti-PDL1 monotherapy.75

Despite the fact that said recurrence is infrequent, the international guidelines recommend the definitive suspension of oncologic treatment in patients that develop grade 3 IMH, or higher. Several works have recently been published confirming that treatment reintroduction in those patients is safe, with an incidence of recurrence in patients with severe IMH (grade 3 or higher) making up 25 to 35% of those patients.88 A retrospective study conducted in the United States, in which 31 patients with grade 3 or grade 4 hepatitis were retreated with immunotherapy (with the same ICI or a different one), showed an incidence of IMH recurrence of 26%. The majority of those patients had grade 3 IMH that appeared at a median time of 27 days after treatment reintroduction.88

As a peculiarity, that US study included patients that had been treated with corticoids, as well as patients that did not receive immunosuppressive treatment, with results similar to those of a recently published Spanish multicenter study,96 in which recurrence was described at approximately 35%. In addition, a greater recurrence in patients with an autoimmune background, defined as the presence of another autoimmune disease and/or the presence of antinuclear antibodies, was reported in the Spanish study.

The importance, with respect to immunotherapy reintroduction, lies not only in what can or cannot be done, but also in offering the patient efficacious therapeutic tools in the treatment of oncologic disease that tends to be found at advanced stages. If immunotherapy is contraindicated due to having presented with a previous episode of IMH, the therapeutic arsenal for those patients is most likely substantially limited, consequently increasing the risk for disease progression, quality of life deterioration, and death. Therefore, retreatment is an option that should be re-evaluated in all patients with IMH. In addition to the therapeutic alternatives available, the oncologic and functional situation, as well as the wishes of the patient, should be taken into account.

ConclusionsThere are still many questions to be answered with respect to the most adequate management of severe adverse effects in patients undergoing treatment with ICIs. As we have seen, some such critically important questions are the grading of the disease, the need or not for treatment based on toxicity severity and the underlying disease, and the possibility of reintroduction of immunotherapy after a severe adverse event or the potential recurrence risk of said toxicity. In addition, and as we have seen in this review, the underlying disease of patients treated with immunotherapy also influences the type and severity of the adverse events. But beyond the development or not of IMH, other aspects, such as the risk of reactivation of HBV or HCV (there is a much lower risk for HCV), the potential reactivation of latent infections, such as tuberculosis, and the interaction of the drugs indicated for the underlying disease in some patients (immunosuppressants, biologics, and other therapies), increase the complexity of immunotherapy more every day. Thus, meeting the challenges involved in managing severe adverse events requires a multidisciplinary and collaborative effort, and if possible, the development of interdisciplinary units that offer a comprehensive diagnosis, together with a rapid and adequate management of these patients. Correctly educating patients, as well as the professionals involved in the care of adverse effects related to ICI therapy, proactive follow-up, and timely multidisciplinary management of said effects, is correlated with better overall results for the patient, signifying less likelihood of interrupting immunotherapy, and in the end, a greater possibility of survival.97

In summary, multidisciplinary management with experience in both the control of concomitant comorbidities and the management of adverse effects can increase the overall efficacy of the treatment of these patients. For many of them, immunotherapy will be one of their last therapeutic alternatives, if not the last.98

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study/article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.