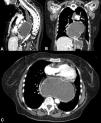

A 70-year-old woman had a past medical history of mixed large and small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, with a focal component of endometrial adenocarcinoma that metastasized to the lung, as well as a history of a large hiatal hernia (>5 cm) (Fig. 1). She was admitted to the emergency department due to oppressive chest pain, radiating into the neck, that was exacerbated with food intake. Laboratory work-up reported leukocytes 21.3 × 109/L, neutrophils 18.3 × 109/L, C-reactive protein 37.8 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 241 IU/L, and lactate 2.7 mmol/L. Cardiac evaluation showed no alterations and angiotomography was negative for pulmonary thromboembolism but revealed an “hourglass” hiatal hernia (Fig. 2). Decompression was carried out with a nasogastric tube, and due to suspected gastric strangulation, the patient underwent hiatal hernia reduction and laparoscopic gastropexy, resulting in pain improvement. Hiatal hernias are divided into four types, the most complex of which are the paraesophageal hernias (types III and IV), accounting for 5–10% of cases (Fig. 3). In addition to the stomach, this type of hernia can contain parts of other abdominal viscera, such as the colon, small bowel, pancreas, or spleen. Acute complications of strangulation or ischemia warrant immediate decompression.

Multidetector computed tomography with intravenous contrast and multiplanar reconstruction, identifying the presence of the body and fundus of the stomach at the intrathoracic level secondary to a paraesophageal hernia, with important distension of the gastric chamber and esophagus (A) sagittal reconstruction; B) coronal reconstruction; C) axial view).

No financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.