“Serrated polyps” is the term used for epithelial lesions of the colon and rectum that have a “sawtooth” pattern on the polyp's surface and crypt epithelium. The so-called serrated pathway describes the progression of sessile serrated adenomas and traditional serrated adenomas to colorectal cancer. Said pathway is well recognized as an alternative mechanism of carcinogenesis and accounts for 15-30% of the cases of colorectal cancer. It also explains a large number of the cases of interval colorectal cancer. Thus, due to their usually aggressive and uncertain behavior, serrated polyps are of the utmost importance in colorectal cancer screening. Our aim was to review the history, current nomenclature, pathophysiology, morphology, treatment, and surveillance of serrated polyps.

«Pólipos serrados» es el término utilizado para describir lesiones epiteliales del colon y recto que demuestran un patrón de «dientes de sierra» de la superficie y epitelio de las criptas. La llamada vía serrada describe la progresión de adenomas serrados sésiles y adenomas serrados tradicionales a cáncer colorrectal. Esta vía está bien reconocida como un mecanismo de carcinogénesis alternativo, el cual representa el 15-30% de los casos de cáncer colorrectal, explicando además una proporción significativa de los casos de cáncer colorrectal de intervalo. Por tal motivo, debido a su comportamiento incierto y usualmente agresivo, los pólipos serrados son un tema de suma relevancia en el cribado de cáncer colorrectal. Nuestro objetivo fue revisar la historia, nomenclatura actual, fisiopatología, características morfológicas, tratamiento y vigilancia de los pólipos serrados.

The term “serrated polyps” is used to describe epithelial lesions of the colon and rectum demonstrating a histologic “sawtooth” pattern of the polyp’s surface and crypt epithelium.1 Previously, all lesions showing those characteristics were considered hyperplastic polyps (HPs).2 In recent decades, colorectal polyps, in general, were divided into 2 types: HPs and adenomas. Adenomas were considered the only precursor of colorectal cancer (CRC), and HPs were considered lesions with no malignant potential.2 However, reports from 3 decades ago described the association of HPs with the potential for malignant transformation. In 1990, Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser specified a type of mixed colorectal polyp that shared adenoma and HP features, exhibiting architectural but not cytologic features of a HP, and called them “traditional serrated adenomas”, emphasizing the neoplastic potential of those lesions.3 In 1996, Torlakovic et al. first described what we now know as sessile serrated adenomas. Those lesions are characterized by displaying an abnormal architecture with no cytologic dysplasia.4

Currently, the different morphologic and molecular profiles of those serrated lesions and their potential for malignant transformation are well known. The so-called serrated pathway describes the progression of serrated adenomas and traditional serrated adenomas to CRC. Said pathway is well recognized as an alternative mechanism of colorectal carcinogenesis that accounts for 15% to 30% of cases of colorectal cancer.5 In addition, the lack of identification of those serrated lesions could explain a significant proportion of interval CRCs.6,7

The current nomenclature of serrated polyps, according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification, is divided into HPs, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps (SSA/Ps), and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs).8 The accurate differentiation of each of those lesions is crucial because of their different potential for malignant transformation.9 Unlike HPs, which are the most common serrated lesions (80-90%) found in the colon and rectum, SSA/Ps and TSAs are thought to have malignant transformation potential. SSA/Ps comprise 8% to 20% of the serrated lesions of the colon and rectum and therefore are considered the most relevant of the serrated lesions, given the rarity of TSAs.10,11

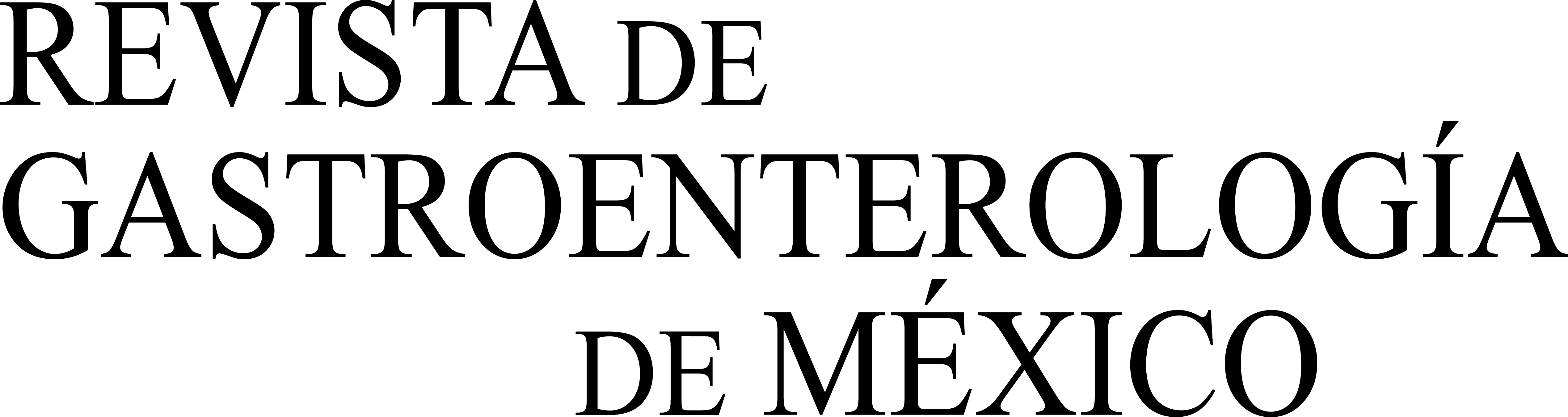

Serrated lesion subtypesHyperplastic polypsTrue HPs are the most common serrated lesion subtype. They account for 70% to 95% of all serrated polyps12 and 25% to 30% of all colonic polyps,13 and are characterized by their lack of malignant potential. HPs predominate in the distal colon and they are usually smaller than 5 mm. Endoscopically, they are flat or slightly elevated lesions that are transparent or pale10,11 (Fig. 1A). Histologically, HPs are characterized by straight crypts, with ‘serration’ typically restricted to the upper half14 (Fig. 1B).

A) Endoscopic appearance of a hyperplastic polyp. It is characterized by a flat or slightly elevated lesion that is transparent or pale. B) Histologic appearance of hyperplastic polyp, showing elongated crypts, a higher number of cells than in normal mucosa, conserved structure and maturation, a normal number of goblet and absorptive cells, with regular nucleus and basal distribution. A chronic inflammatory type of lymphocytic predominance can be seen in the lamina propria.

HPs are also subclassified as microvesicular HPs, goblet cell-rich HPs, and mucin-poor HPs, based on the type of mucin pattern.15 The microvesicular subtype is the most common, making up 60% of all HPs.12 Histologically, they are characterized by columnar cells with multiple small cytoplasmic vacuoles (microvesicular).16

Sessile serrated adenoma/polypSSA/Ps are the most relevant of the serrated lesions, not only because of their malignant potential, but also for their difficult detection. They are most commonly located in the right colon and account for approximately 5% to 25% of all serrated polyps12,13 and 1.7% to 9% of all colonic polyps.17,18 The presence of an SSA/P is associated with female sex and an increased number of polyps in the colonoscopy examination.17,19

Expertise and image enhancing endoscopy techniques are necessary for the detection and proper resection of SSA/Ps.20 Endoscopically, they are usually > 10 mm, flat and slightly elevated, with inconspicuous margins. Their color is similar to that of the surrounding mucosa, with a cloud-like surface, the underlying mucosal vascular pattern is interrupted, and they are frequently covered by a yellow mucous layer10,14,21 (Figs. 2A and B). Histologically, SSA/Ps present with distorted crypt architecture, with marked serration located at the base of the crypts. Basal crypts are dilated and laterally extended into a mucus-filled L or inverted T shape, with the presence of mature cells above the muscularis mucosae9,14 (Fig. 2C).

Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. A) A mostly flat sessile serrated polyp in the right colon. Note the color similar to that of the adjacent normal colon, the paucity of blood vessels on the surface of the lesion, and the accumulation of yellow “debris” at the edges. B) A sessile serrated polyp in the right colon. Note the prominent “yellow mucus cap.” C) Histologic appearance of a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. It has distorted crypt architecture, with marked serration at the base of the crypts; basal crypts are dilated.

(endoscopic images taken with authorization: Rex D. Serrated Polyps in the Colon. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 10 (10). Histologic image was taken with authorization: Kuo E. Sessile serrated adenoma [accessed July 2, 2020]. Available at:

http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumorsessileserrated.html.

Even though TSAs also have a risk for malignant transformation, they are the least frequent type of serrated lesions. They account for approximately 1% of all colorectal polyps13 and are more commonly located in the distal colon. Endoscopically, with narrow band imaging (NBI), they appear as superficial or protruding and sometimes pedunculated lesions and are usually > 5 mm in size, with dilated vessels.13,22 Histologically, TSAs are characterized by a protuberant, villous growth pattern.13 The presence of ectopic crypts perpendicular to the axis of the villous structures, cytologic atypia, and prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm are their characteristic features23 (Fig. 3).

Histologic section of a traditional serrated adenoma, showing a protuberant villiform growth pattern with slit-like serrations.

Taken from: Kuo E, Gonzalez R. Traditional serrated adenoma [accessed July 2, 2020]. Available at:

http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumortraditionalserratedadenoma.html.

Table 1 and Table 2 provide a summary of the main clinical endoscopic and histopathologic characteristics of serrated polyps, respectively.

Main clinical and endoscopic characteristics of serrated polyps.

| Hyperplastic polyps | SSA/P | TSA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Very common | Common | Rare |

| Sex predominance | None | Female | None |

| Predominant location | Left colon and rectum | Right colon | Left colon and rectum |

| Size | < 5 mm | > 10 mm | > 5 mm |

| Endoscopic appearance | Flat or slightly elevated lesions that are transparent or pale | Sessile, inconspicuous, yellow margins, covered by a mucous layer | Sessile |

| Malignant potential | No | Yes | Yes |

SSA/P: sessile serrated adenoma/polyp; TSA: traditional serrated adenoma.

Main histopathologic characteristics of serrated polyps.95,96

| Hyperplastic polyps(microvesicular) | SSA/P | TSA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crypt architecture | Straight crypts | Distorted crypt architecture | Protuberant and villiform growth pattern |

| Serrations | Restricted to the upper half of the crypts | Located at the base of the crypt | Slit-like, clefted serrations |

| Basal crypt | Narrow | Dilated and laterally extended (L or inverted T) | Ectopic crypt foci |

| Crypt branching | No | Yes | No |

| Proliferative zone | Located at the basal third | Not at its usual location at the base of the crypts | Abnormally positioned crypts, with bases not seated at the muscularis mucosae |

| Cell maturation | Maturation from crypt base to surface | Base of the crypt | Loss of orientation towards the muscularis mucosae |

| Main characteristic feature | Straight crypts with upper serration | Inverted growth and dilated basal crypt | Slit-like serrations, ectopic crypts, cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm |

SSA/P: sessile serrated adenoma/polyp; TSA: traditional serrated adenoma.

The serrated pathway is recognized as the second most important pathway leading to CRC, after the adenoma-carcinoma pathway. In regard to serrated polyps and CRC, the biology is heterogeneous, culminating in 2 main postulated serrated pathways to CRC: the BRAF mutation pathway and the KRAS mutation pathway.

The BRAF mutation pathway is characterized by high levels of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), which leads to the silencing of the hMLH1 mismatch repair gene, resulting in high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and the consequent evolution into dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and ultimately, CRC (BRAF mutation/CIMP-high/MSI-H/).24 Colorectal carcinomas following the BRAF mutation/CIMP-high/MSI-H pathway make up the majority of sporadic non-syndromic CRCs with MSI-H, accounting for approximately 12-15% of all CRCs.7

In contrast, the KRAS mutation pathway is characterized by a low level of CpG island methylation, with no inactivation of the hMHL1 mismatch repair gene, and with microsatellite stability (KRAS mutation/CIMP-low/MSS). Thus, the main stimulus toward carcinogenesis in those cases is the mutation of suppressor genes, as is the case with SLIT-2 and p53.7,25 Colorectal carcinoma that follows the KRAS mutation/CIMP-low/MSS pathway makes up approximately 5% of all CRC.26

By correlating the histologic characteristics of serrated polyps with their molecular genetic features, SSAs and TSAs appear to be two genetically distinct entities. Predominantly, SSAs with dysplasia have the BRAF mutation, whereas TSAs have the KRAS mutation.27

Histologic correlation with endoscopic imagingUnlike adenomas, whose incidence is around 30-40% in the overall population, serrated lesions are found in only 5-8%. Nevertheless, they may be underestimated because of the difficulty in identifying them in routine screening colonoscopy.28,29

In general, SSA/Ps can be differentiated from HPs by the presence of a mucous cap and dilated pits (type II open pit pattern).22,30 However, several other specific endoscopic features, such as indistinct borders, a cloud-like surface, irregular shape, and dark spots inside the crypts, on high-resolution white-light endoscopy and NBI, have aided in identifying SSA/P histology with a high degree of accuracy.21

The distinction between non-malignant SSA/Ps and SSA/Ps with dysplasia is of major relevance. The NBI technique has been shown to be of great value in both identifying the high-risk features of malignancy in serrated lesions and increasing the detection of proximal colon serrated lesions.31 The detection of irregular vessels through magnifying NBI has 100% sensitivity, 99% specificity, an 86% positive predictive value, and a 100% negative predictive value for identifying cancer coexisting with SSA/P.30 Other characteristics, such as lesion size (OR 1.9 for dysplasia for every 10 mm increase in lesion size), increasing age (OR 1.69 per decade), Kudo III, IV, or V (adenomatous) pit pattern, and the 0Is component of the Paris classification have been shown to correlate well with dysplasia.32

Interval cancersInterval cancers are defined as CRC diagnosed within 5 years of a complete / clearing colonoscopy. They account for approximately 2-6% of all CRC.33,34

Several factors have been identified as a cause of interval cancers. Missed lesions due to suboptimal colon preparation, incomplete examination of the colon, incomplete resection of polyps, and missed or unrecognized lesions (e.g. SSA/P) predominantly located in the right colon are the main factors associated with interval CRC.33

There is evidence that sporadic CRC may arise from SSA/P lesions. Firstly, interval CRC occurs 3 times more frequently in the right colon, compared with sporadic cancer.33 In addition, interval colon cancer is 4 times more commonly associated with mismatch repair gene dysfunction than sporadic cancer.35,36 Those data suggest a possible BRAF mutation serrated origin.7 Besides the factors previously mentioned, CIMP-H and MSI-H cancers present accelerated growth or evolution, becoming malignant in fewer than 10 years from the last colonoscopy examination.13

Progression to malignancyThe rate of serrated lesions that progress to carcinoma is not clear and may differ, depending on the occurrence of MSI-H. Among the serrated lesions with malignant potential, the rate of dysplasia is higher in TSA (9.3%) compared with SSA/P (2%).37 The reported appearance of high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma in serrated adenomas is between 2-3.2%,37,38 which is lower than the 9.3% rate in conventional adenomas.37

A 5% risk of serrated cancer following the endoscopic resection of an index serrated adenoma has been reported.39 The fact that the rate of progression to non-serrated carcinoma is greater when conventional adenomas are not resected (14.3%) suggests that the rate of neoplastic transformation for non-resected serrated adenomas is greater than 5%.39

Regarding the time of progression to malignancy, a case report showed a rapid progression of SSA/P to early invasive carcinoma within 8 months.40 However, a study analyzing 106 serrated polyps, most of which were from the right colon, that preceded 91 MSI-adenocarcinomas showed slower progression, with a mean time interval between polypectomy and the development of subsequent adenocarcinoma of 7.3 years (range 1.2-19.3 years).41 Even though there is no clear evidence of the proportion and rate of progression, the malignant potential of serrated lesions has been well documented, making up a significant proportion of overall CRC cases. Therefore, serrated lesions should be considered an important target for CRC prevention, to impact the incidence of right CRC.

Metachronous and synchronous cancerIn patients with serrated lesions (HP, SSA/P, or TSA), the occurrence of metachronous serrated CRC occurred in 5% of cases, after a mean of 14.25 years, following index examination.39 Whether serrated lesions increase the risk of metachronous neoplasia, in comparison with conventional adenomas, is a subject of debate. Some reports showed a risk of metachronous neoplasia in 2-5% of patients with serrated lesions,39,42 which was not significantly different from the CRC rate in patients with conventional adenoma (2.2%).39 Other studies reported a significantly higher risk of metachronous neoplasia in patients with SSA/P (12.5%) than in patients with HP (1.8%) and adenomas (1.8%).43

The association between serrated lesions and synchronous neoplasia is more certain.18,44 The rate of additional serrated lesions (SSA/Ps, SSA/Ps with dysplasia, and TSAs) in patients with a resected index SSA/P was 18%, compared with 5% in a control population.45 Proximal and large (≥ 10 mm) HPs, as well as proximal and large (≥ 10 mm) SSA/Ps, have been associated with synchronous advanced neoplasia.18 The rate of synchronous advanced neoplasia is about 17.8% in proximal HP and SSA/P, compared with 8% in non-proximal polyps, and the rate of synchronous advanced neoplasia is about 27% in large polyps (HP and SSA/P) > 10 mm, compared with smaller polyps (8.6%).18

Risk factors for serrated lesionsMultiple factors, such as ethnicity, family history, and modifiable lifestyle and diet, have been associated with a higher risk for serrated polyps. In connection with race/ethnicity, the risk of serrated polyps (in the left colon) is lower in African Americans (RR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.50-0.85) and Hispanics (RR: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.20-0.55), compared with Whites.46 A family history of CRC or polyps is associated with serrated lesions in the right colon.46,47

The main modifiable lifestyle factors associated with serrated lesions are obesity and cigarette smoking.46,48 A body mass index ≥ 30 was associated with a 27% increase in the risk of serrated lesion in the left colon, compared with normal weight. Current cigarette smoking increased the risk of left serrated lesions (RR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.80-2.65) and of left-sided advanced serrated lesions (RR: 3.42, 95% CI: 1.91-6.11), compared with no smoking.46 Heavy alcohol drinking (≥ 14 drinks/week) was also significantly associated with an increased risk of advanced neoplasia (OR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.37-5.15).48 Among the dietary factors, increased fat intake increased the risk of serrated lesion in both the right colon (RR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.03-1.56) and the left colon (RR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.01-2.10). Red meat intake significantly increased the risk of left advanced serrated polyps (RR: 1.93, 95% CI: 0.97-3.84).46

With respect to treatment prescription, the use of aspirin (81 mg) reduced the risk of non-advanced serrated lesions in the right colon. A higher dose of aspirin (325 mg) provided a protective effect for advanced lesions in the right colon.46 Cereal fiber intake > 4.2 g per day (RR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.43-0.98) and vitamin D intake > 645 U per day (RR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.39-0.97) were also associated with a reduced risk for advanced neoplasia.48

Serrated polyposis syndromeSerrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is characterized by the development of multiple serrated polyps throughout the colon. Since the publication of the fourth edition of the WHO criteria for SPS diagnosis in 2010,15 the understanding of SPS has improved substantially, resulting in an update of the 2010 diagnostic criteria, incorporated in the fifth edition of the WHO classification of Digestive System Tumours in 2019.8 The following are the updated criteria for SPS diagnosis:

- I

More than or equal to 5 serrated lesions/polyps proximal to the rectum, all ≥ 5 mm in size, with at least 2 ≥ 10 mm.

- II

More than 20 serrated lesions/polyps of any size distributed throughout the large bowel, with ≥ 5 proximal to the rectum.

The 2019 updated diagnostic criteria for SPS made several important changes, the most notable of which was the elimination of criterion II (2010), whereas criterion I (2010) and criterion III (2010) underwent minor modifications. The 2010 criterion I only included polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon, whereas the 2019 criterion I now includes serrated polyps in the sigmoid colon. In addition, all serrated polyps in the 2019 criterion I must now be ≥ 5 mm, excluding diminutive serrated polyps for the diagnosis of SPS (Table 3).

The 2010 and 2019 World Health Organization criteria for SPS diagnosis.97

| 2010 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| Criterion I. ≥ 5 serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon with two or more of them > 10 mm | → | Criterion I. ≥ 5 Serrated lesions/polyps proximal to the rectum, all ≥ 5 mm in size, with at least 2 ≥ 10 mm. |

| Criterion II. Any number of serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon in an individual with a first-degree relative with SPS | ||

| Criterion III. > 20 serrated polyps of any size spread throughout the colon | → | Criterion II. > 20 serrated lesions/polyps of any size distributed throughout the large bowel, with ≥ 5 proximal to the rectum. |

SPS: serrated polyposis syndrome.

Even though that classification provides standardized diagnostic criteria, enabling the comparison between studies, it is somewhat arbitrary and restrictive. Thus, patients with 5 serrated polyps, only one of which is > 10 mm in diameter, or patients with 10 to 20 serrated polyps < 10 mm, do not fit the SPS definition. However, even though that subgroup does not entirely meet the WHO definition of SPS, it still has clinical significance.

A retrospective study performed at the Cleveland Clinic and the Genomic Medicine Institute analyzed patients with serrated polyps, recognizing 3 phenotypic patterns: large sessile (> 10 mm) serrated polyps in the right colon (right-sided phenotype 48%); multiple, small hyperplastic polyps in the left colon (left-sided phenotype 16%); and a third phenotype with characteristics of the previous two types (mixed phenotype 37%).49 The 3 phenotypes had a similar incidence of CRC (right 27%, left 28%, and mixed 21%), with the right-sided phenotype presenting more SSA/Ps and tending to develop CRC at a younger age.49

The prevalence of SPS is low (< 0.1%) in colonoscopy screening programs.18,50 In a selected population with positive fecal immunochemical tests, prevalence was expectedly higher (0.34-0.66%).51,52 Patients with SPS and their relatives are at an increased risk of CRC, with an incidence between 7% and 70%6,53–55 and an interval cancer risk of 2% to 7%.6,53,56 The main predictors of CRC in patients with SPS are the number of proximal SSA/Ps and the presence of high-grade dysplasia in a proximal SSA/P.53

Unlike other hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis, SPS does not have a simple Mendelian inheritance pattern.57 Interestingly, CRC in patients with SPS has been reported to follow both the serrated pathway and the traditional adenoma-carcinoma pathway.56 Patients with SPS and their relatives are also at an increased risk for extracolonic neoplasia (prostate, skin, leukemia/lymphoma, breast, lung, etc.).49

Serrated lesion detectionColonoscopy is the most accurate and preferred method for the detection of colonic polyps.58 Because of the relatively slow progression of serrated polyps, their detection and endoscopic resection can halt their progression to cancer. Despite this, colonoscopic surveillance programs have had a positive impact on decreasing the incidence of CRC only in the left colon, whereas the incidence and mortality associated with CRC in the right colon has not changed.59 The lack of impact on the incidence of right CRC is implied by the lack of identification of SSA/Ps in the right colon during screening colonoscopies.59

Several interventions have been carried out to improve serrated lesion detection rates.60 Image-enhanced endoscopy techniques, such as chromoendoscopy and magnification endoscopy, have improved HP detection.61–63 High-definition colonoscopies, however, have not demonstrated an improvement in serrated lesion detection.64,65 Chromoendoscopy has been shown to improve the detection of HPs from 23% to 45% in the entire colon and from 9% to 16% in the right colon.58 Indigo carmine, the most common dye spraying agent used in colon chromoendoscopy, delimits the lesions more clearly, particularly flat proximal hyperplastic polyps. On the other hand, acetic acid spray, in combination with NBI, has delineated SSA/Ps more accurately, enabling complete resection.66 Interestingly, the acetic acid-indigo carmine mixture has been reported to enhance the margin of the lesion, through a whitish change of the lesion surface.67 However, prospective visibility/detection studies using the aforementioned techniques are required, before a strong recommendation can be given.

Digital chromoendoscopy (NBI, FICE, or iSCAN) has been used to improve serrated lesion detection rates. Nevertheless, a meta-analysis comparing NBI vs white light endoscopy found no improvement in the adenoma detection rate.68 The use of FICE in a multicenter prospective study displayed no advantage over white light endoscopy, in terms of the general adenoma detection rate and HP identification.69 The use of LASEREO, Blue Laser Imaging (BLI), and Linked Color Imaging (LCI) improved the diagnostic accuracy of serrated lesions in the colon and rectum, compared with white light endoscopy, alone.70 Even though the use of BLI and LCI remained superior to white light endoscopy, more studies are needed to determine which of them is superior.70 The utilization of i-SCAN was not associated with an improvement in adenoma detection or the prevention of missed polyps.71 A randomized controlled trial comparing the rate of SSA/P detection between i-SCAN 1 vs standard high-definition white-light colonoscopy showed no difference.72 We did not find any studies specifically comparing different i-SCAN effects, with respect to serrated lesion detection.

Another intervention, such as longer withdrawal time (above 6 minutes), has been shown to improve the serrated polyp detection rate, with a maximum benefit at 9 minutes.73,74 Performing retroflexion in the right colon has been described as a safe technique that modestly improves the polyp and adenoma detection rates.75 In contrast to reports of bowel preparation improving the adenoma detection rate, it has had no impact on improving the serrated lesion detection rate. A serrated polyp detection rate of 8.8% has been found in patients with excellent bowel preparation versus 8.9% in those with fair bowel preparation.76 Other factors, such as formal gastroenterology training, a higher procedure volume, and interestingly, fewer years in practice (≤ 9 years since the completion of training) have had a positive influence on the detection of serrated lesions.77

NBI enables the identification of SSA/Ps by discerning their irregular shape and dark spots inside the crypts, which indicate crypt dilatation, a characteristic histologic feature of SSA/Ps.78,79 On the other hand, magnifying chromoendoscopy enables SSA/Ps with dysplasia or carcinoma to be differentiated from those without dysplasia, by identifying endoscopic features, such as semipedunculated morphologies, double elevations, central depressions, and reddishness, as well as the presence of IIIL, IV, VI, or VN pit patterns.78,79

More recently, artificial intelligence (convolutional neural networks) using deep learning models, with video/image training sets, has improved colonoscopic polyp detection and characterization.80,81 This emerging technology has shown a high level of accuracy for detecting SSA/Ps, with an area under the curve of 0.94, a positive predictive value of 0.93, and a negative predictive value of 0.96.82

Endoscopic resection of serrated lesionsThe complete resection of serrated lesions is the primary aim for preventing the development of CRC. The resection techniques for managing colonic lesions are the same as those used for conventional adenomas. Cold snare polypectomy is a safe technique for the resection of diminutive sessile polyps and has a high polyp retrieval rate (98-100%).83,84 For larger superficial, elevated, or poorly defined serrated lesions, endoscopic mucosal resection, with prior submucosal injection (injection and cut), is the preferred technique.85,86 Variations of endoscopic mucosal resection techniques, such as inject-lift-cut, cap-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic mucosal resection with ligation, have had good results.85,87

The British Society of Gastroenterology position statement on serrated polyps in the colon and rectum recommends performing the resection of complex lesions (large lesion in the right colon) in centers that have operators with expertise in the recognition and endoscopic management of those lesions.60 That recommendation is supported by the results of several studies demonstrating a high risk of incomplete endoscopic resection and complications, associated with resection of large sessile polyps in the right colon.88–90 Endoscopists attempting to treat those lesions must achieve the competence and standards established in the international guidelines on the management of large non-polypoid colorectal polyps.90

After piecemeal resection of large serrated lesions > 20 mm, and before enrolling the patients in a long surveillance program, endoscopic revision is initially advised after 3-6 months, and then one year after resection of the index lesion, for the purpose of examining the polypectomy site, in search of recurrence.91

Serrated lesion surveillanceThe recommendation for follow-up interval surveillance is based on the intrinsic lesion/patient risk.60 Patients with multiple serrated polyps that meet the criteria for SPS are high-risk cases. Once the lesions have been resected, the recommended surveillance colonoscopy interval in patients with SPS is every one or 2 years. In patients with high-risk lesions, such as large SSA/Ps > 10 mm, or with associated dysplasia or TSAs,92 the recommended interval for surveillance colonoscopy is 3 years.93,94 Lower-risk lesions are HPs or serrated lesions < 10 mm, with no associated dysplasia. There is no evidence supporting an indication for colonoscopic surveillance, unless the lesions meet the SPS criteria, with respect to size, location, or number.60Table 4 provides a summary of the recommended surveillance intervals for serrated lesions.

Surveillance recommendation after serrated polyp resection.7,60

| Risk | Description of lesions | Surveillance interval |

|---|---|---|

| Low-risk lesions | Hyperplastic polyps * | No surveillance |

| SSA/P < 10 mm with no dysplasia * | < 3 polyps ------- 5 years≥ 3 polyps ------- 3 years | |

| High-risk lesions | SSA/P ≥ 10 mm or dysplasia | 3 years** |

| TSA | ||

| SPS | Multiple serrated polyps meeting the SPS criteria | 1-2 years |

SPS: serrated polyposis syndrome; SSA/P: sessile serrated adenoma/polyp; TSA: traditional serrated adenoma.

After piecemeal resection of large serrated lesions > 20 mm, endoscopic revision at 3-6 months is advisable, and again one year after resection of the index lesion, for the purpose of examining the polypectomy site, in search of recurrence, before enrolling the patients in a long surveillance program.

The authors declare that the present review meets the current norms in bioethical investigations, because it is a narrative review, authorization by the ethics committee was not necessary. The authors also declare that this review does not contain any personal information that could identify patients.

Financial disclosureWe received no funding in relation to the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Monreal-Robles R, Jáquez-Quintana JO, Benavides-Salgado DE, González-González JA. Pólipos serrados del colon y el recto: una revisión concisa. Revista de Gastroenterologíade México. 2021;86:276–286.

![Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. A) A mostly flat sessile serrated polyp in the right colon. Note the color similar to that of the adjacent normal colon, the paucity of blood vessels on the surface of the lesion, and the accumulation of yellow “debris” at the edges. B) A sessile serrated polyp in the right colon. Note the prominent “yellow mucus cap.” C) Histologic appearance of a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. It has distorted crypt architecture, with marked serration at the base of the crypts; basal crypts are dilated. (endoscopic images taken with authorization: Rex D. Serrated Polyps in the Colon. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 10 (10). Histologic image was taken with authorization: Kuo E. Sessile serrated adenoma [accessed July 2, 2020]. Available at: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumorsessileserrated.html. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. A) A mostly flat sessile serrated polyp in the right colon. Note the color similar to that of the adjacent normal colon, the paucity of blood vessels on the surface of the lesion, and the accumulation of yellow “debris” at the edges. B) A sessile serrated polyp in the right colon. Note the prominent “yellow mucus cap.” C) Histologic appearance of a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. It has distorted crypt architecture, with marked serration at the base of the crypts; basal crypts are dilated. (endoscopic images taken with authorization: Rex D. Serrated Polyps in the Colon. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 10 (10). Histologic image was taken with authorization: Kuo E. Sessile serrated adenoma [accessed July 2, 2020]. Available at: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumorsessileserrated.html.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/2255534X/0000008600000003/v1_202106290531/S2255534X21000591/v1_202106290531/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w97o/wdEXW47bqlyT1CqG6R0=)

![Histologic section of a traditional serrated adenoma, showing a protuberant villiform growth pattern with slit-like serrations. Taken from: Kuo E, Gonzalez R. Traditional serrated adenoma [accessed July 2, 2020]. Available at: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumortraditionalserratedadenoma.html. Histologic section of a traditional serrated adenoma, showing a protuberant villiform growth pattern with slit-like serrations. Taken from: Kuo E, Gonzalez R. Traditional serrated adenoma [accessed July 2, 2020]. Available at: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colontumortraditionalserratedadenoma.html.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/2255534X/0000008600000003/v1_202106290531/S2255534X21000591/v1_202106290531/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w97o/wdEXW47bqlyT1CqG6R0=)