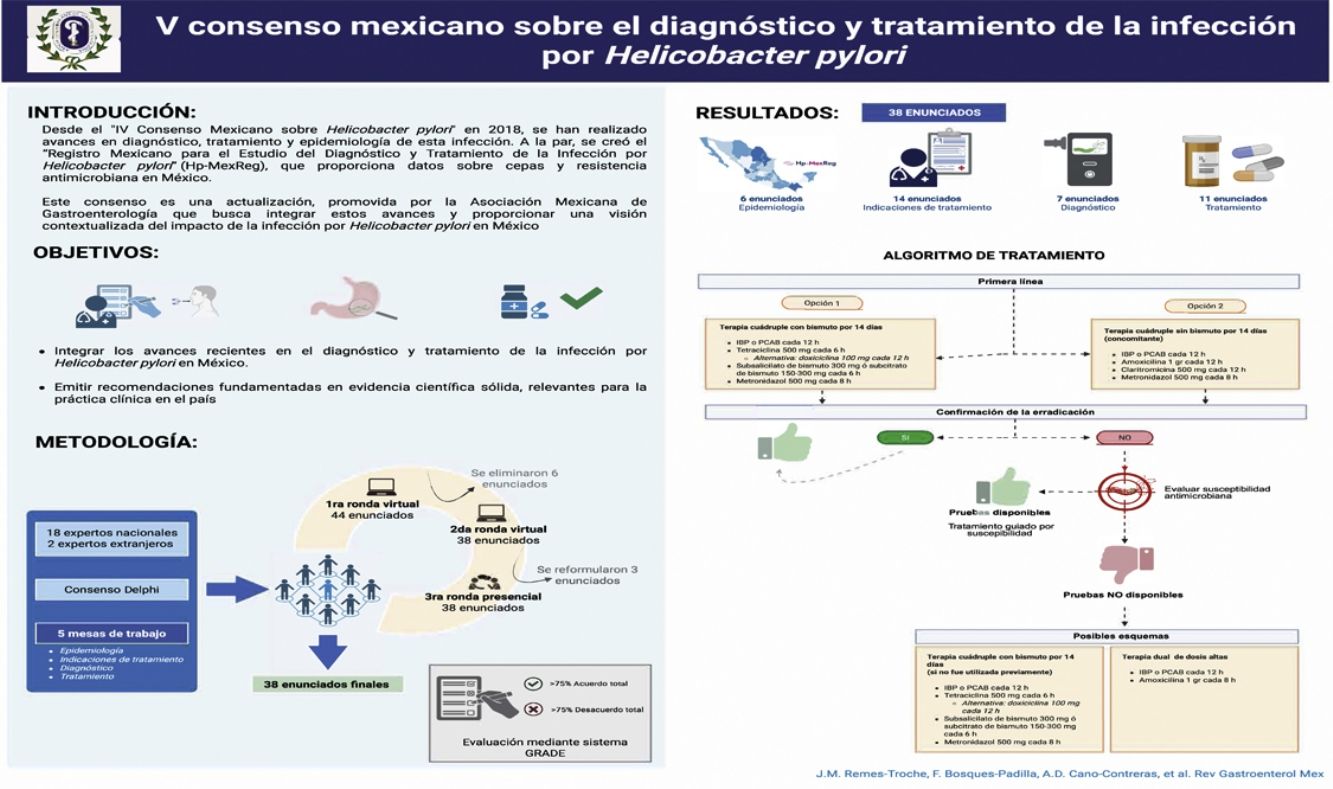

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection remains highly prevalent in Mexico and worldwide. In response to the advances in diagnosis, treatment, and epidemiologic surveillance, the Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología, through a multidisciplinary panel of experts, developed the “Fifth Mexican Consensus on H. pylori” in 2025, providing 38 evidence-based recommendations tailored to the Mexican context. The document highlights the establishment of the Hp-MexReg national registry and its collaboration with Hp-LatamReg and HpRESLA projects, enabling the collection of local data on eradication rates and antimicrobial resistance. The expert group reaffirms the high prevalence of H. pylori in Mexico (70.5%) related to social and sanitation factors, as well as the increase of antibiotic-resistant strains, particularly to clarithromycin and levofloxacin. Regarding diagnosis, the 13C-urea breath test is prioritized as the first-line noninvasive method and eradication of the bacterium should be confirmed at least four weeks after treatment. Regarding treatment, quadruple therapies, with or without bismuth, are recommended over standard triple therapy, and potassium-competitive acid blockers are endorsed as an effective alternative to high-dose proton pump inhibitors. H. pylori eradication is strongly recommended, with emphasis on the clinical scenarios in which it is indicated. The present consensus underscores the need to continue conducting national studies that enable strategies to be adapted to Mexico’s epidemiologic reality.

La infección por Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) continúa siendo muy común en México y a nivel mundial. Ante los avances en diagnóstico, tratamiento y vigilancia epidemiológica, la Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología, a través de un grupo multidisciplinario de expertos, desarrolló el “V Consenso Mexicano sobre H. pylori” en 2025. Este consenso proporciona 38 recomendaciones sustentadas en evidencia, y adaptadas al contexto nacional. El acuerdo destaca la creación del registro nacional Hp-MexReg y su integración con los proyectos Hp-LatamReg y HpRESLA, permitiendo obtener datos locales de tasas de erradicación y resistencia antimicrobiana. El grupo experto reafirma la alta prevalencia de H. pylori en México (70,5%) relacionada con factores sociales y sanitarios, así como el incremento en cepas resistentes, en particular a claritromicina y levofloxacina. En cuanto al diagnóstico, se prioriza la prueba del aliento con urea marcada como método no invasivo de primera elección, y se recomienda confirmar la erradicación al menos cuatro semanas después del tratamiento. En el aspecto terapéutico, se recomiendan las terapias cuádruples con o sin bismuto son superiores a la triple terapia estándar, y se avala el uso de bloqueadores ácidos competitivos del potasio como una alternativa efectiva a altas dosis de inhibidores de la bomba de protones. De forma destacada, se recomienda erradicar H. pylori puntualizando las situaciones clínicas. Este consenso subraya la necesidad de continuar generando estudios nacionales que permitan adaptar las estrategias a la realidad epidemiológica de México.

Since the publication of the “Fourth Mexican Consensus on Helicobacter pylori” in 2018,1 substantial progress has been made in several areas related to this infection, including its diagnosis, treatment, and epidemiologic understanding. The increasing availability of new diagnostic technologies, the evolution of therapeutic strategies, and the incorporation of regional surveillance tools have created the need for a comprehensive update of clinical recommendations for the management of this chronic infection.

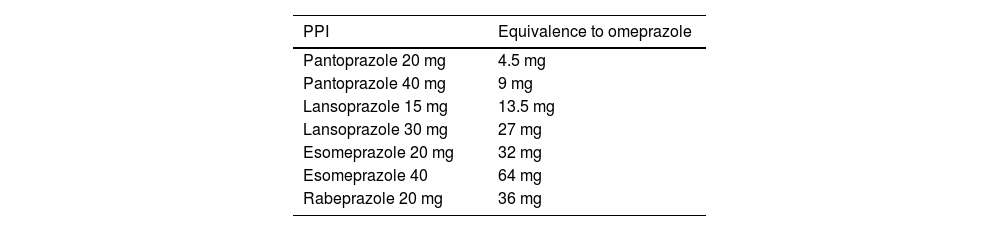

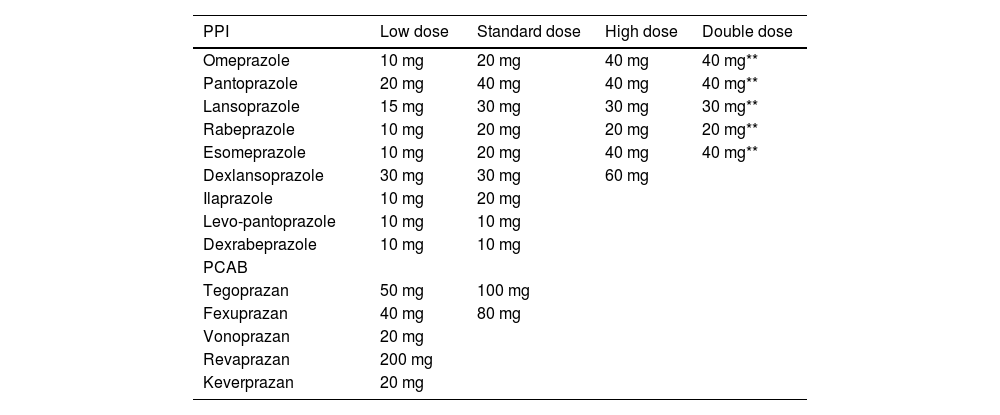

One of the most significant developments in recent years in Mexico has been the creation of the “Mexican Registry for the Study of the Diagnosis and Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection” (Hp-MexReg), which is part of the Latin American collaborative initiative (Hp-LatamReg). This regional effort emerged from a strategic alliance with the European registry (Hp-Eur Reg), enabling the Hp-MexReg to become part of the worldwide registry (Hp World Reg).2 Through the Hp-MexReg, national data are now available that reflect the regional diversity in bacterial strains, antimicrobial resistance rates, and clinical presentation patterns, providing a solid base for guiding clinical and public health decisions. Likewise, this international collaboration has evaluated Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antimicrobial resistance through next-generation sequencing, analyzing 511 samples from treatment-naïve patients from 10 Latin American countries. The findings revealed high resistance rates to clarithromycin (36%) and fluoroquinolones (46.5%), with significant regional variations, and a multidrug resistance rate of 10.7%. These results underline the importance of implementing epidemiologic surveillance programs and developing eradication regimens based on local or regional susceptibility profiles, to optimize treatment and control antimicrobial resistance in the region.3 In parallel, the advent of potassium-competitive acid blockers (PCABs) has transformed the therapeutic landscape. These agents have shown equal or superior efficacy in H. pylori eradication, compared with traditional proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), especially in strains with high antimicrobial resistance. The favorable drug profile and tolerability of PCABs have opened new therapeutic possibilities in a variety of clinical contexts.

The aim of the present update, prompted by the 2025 Executive Board of the Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología, is to incorporate these recent advances and provide recommendations based on solid scientific evidence that are relevant to clinical practice in Mexico. The “Fifth Mexican Consensus on Helicobacter pylori” not only updates the diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines but also promotes a more precise and contextualized vision of the impact of this infection on our country.

MethodsThe consensus utilized the Delphi process, following previously described methodology.4 The working group included 20 national and international experts who were placed into four working subgroups: (1) epidemiology, (2) eradication indications, (3) diagnosis, and (4) treatment. The coordinators (ADCC, FBP, JMRT, and JAVR) of the working subgroups carried out a thorough search on the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed (MEDLINE), Ovid (EMBASE), LILACS, CINAHL, BioMed Central, and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). The search covered studies published between January 1, 2010, and November 31, 2024. The search criteria included the following terms: “H. pylori” combined with: “epidemiology”, “incidence”, “prevalence”, “Mexico”, “risk factors”, “indications”, “diagnosis”, “differential diagnosis”, “treatment”, “antibiotics”, “therapy”, “treatment”, “gastric cancer”, “management”, “review”, “guidelines”, “resistance”, and “meta-analysis”, and their Spanish equivalents. The entire bibliography was available to the consensus participants. The complete search strategy by database, and the terms employed, are available in Appendix A (Supplementary Material).

Each general coordinator led a working subgroup, convening virtual meetings with the respective members to propose and draft the relevant statements. In this first stage, 44 statements were proposed and underwent a first anonymous electronic vote (December 2, 2024, to January 6, 2025), to evaluate the wording and content of the statements. The consensus participants cast their votes, using the following options: (a) in complete agreement (b) in partial agreement, (c) uncertain, (d) in partial disagreement, and (e) in complete disagreement.

After completion of the first round of voting, the coordinators made the corresponding modifications. The statements that reached complete agreement above 75% were kept and those that had complete disagreement above 75% were eliminated. The statements with agreement <75% and disagreement <75% were reviewed and restructured. After that phase (December 2, 2024, to January 6, 2025) six statements were eliminated and/or merged, resulting in a total of 38 statements that underwent a second round of anonymous electronic voting (January 30 to February 10, 2025). Based on the comments received, four statements that did not reach 75% agreement were modified by the coordinators, who made the necessary adjustments for their presentation at the in-person meeting on March 20, 2025, in Morelia, Michoacán. During that session, the agreements were ratified, and the recommendation proposal was prepared, according to the GRADE system (Strength of Recommendations and Quality of Evidence).5

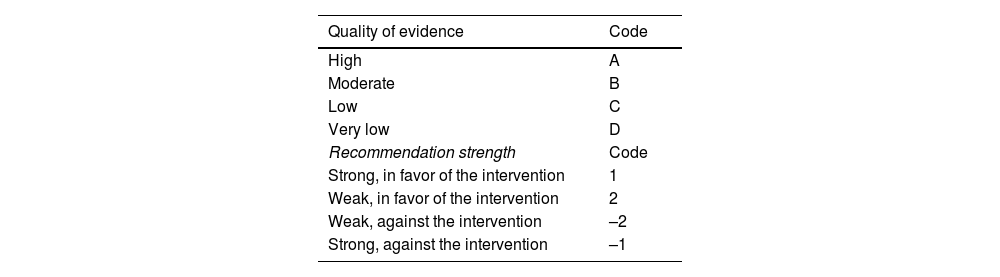

Under the GRADE system, the quality of evidence is graded, not only on study design or methodology, but also in relation to a clearly formulated question and its corresponding clinical outcome,6 classifying the evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low. Likewise, the GRADE system defines the strength of a recommendation as strong or weak, in favor of or against the intervention or statement. Importantly, the strength of recommendation is determined only in the context of diagnostic tests and therapeutic interventions. Table 1 shows the quality of evidence codes in upper case letters employed by the GRADE system, followed by a number indicating the strength of the recommendation in favor of or against the intervention.

Evaluation through the GRADE system and evidence integration.

| Quality of evidence | Code |

|---|---|

| High | A |

| Moderate | B |

| Low | C |

| Very low | D |

| Recommendation strength | Code |

| Strong, in favor of the intervention | 1 |

| Weak, in favor of the intervention | 2 |

| Weak, against the intervention | –2 |

| Strong, against the intervention | –1 |

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

During the in-person meeting, the statements with agreement >75% were ratified. Those not reaching that threshold in the previous voting rounds (n = 3) were discussed further, in an effort to reach agreement. If not reached, the statements were eliminated or voted on again. During the discussions, three new statements were formulated to replace those that did not reach agreement in the previous rounds and underwent the same voting process. When the discussions were concluded, all participants unanimously recognized the urgent need for more robust national studies that accurately reflect the epidemiologic, clinical, and therapeutic reality of H. pylori in Mexico.

Once the statements were agreed upon, the coordinators drafted the present document, which was then reviewed and approved by all the participants.

The 38 statements forming part of the consensus follow below.

Epidemiology- 1

In the past decade, the worldwide prevalence of H. pylori infection is estimated at close to 50%.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A

H. pylori infection remains one of the most prevalent chronic infectious diseases worldwide, with an estimated global prevalence close to 50%, according to two recent systematic reviews.7,8 The global prevalence of H. pylori in adults decreased from 52.6% (95% CI 49.6%–55.6%) before 1990 to 43.9% (95% CI 42.3%–45.5%) between 2015 and 2022. However, in children and adolescents, the prevalence during that same period of time was still considerably high, at 35.1% (95% CI 30.5%–40.1%).7,8 Temporal trend and multivariate regression analyses show a 15.9% decrease in global prevalence in adults (95% CI −20.5% to −11.3%). Those findings suggest reduced infection transmission in adults, possibly related to better living conditions, greater access to potable water, improved sanitation, and antibiotic use. Nevertheless, challenges persist in children and adolescents in many parts of the world, indicating the need for more effective prevention strategies early in life.

There is a marked regional variability throughout the world.7,8 Africa and the Middle East are the regions with the highest infection rates, largely reflecting poorer socioeconomic conditions and sanitation. In contrast, the lowest prevalence (40%) is reported for Europe. Prevalence in Latin America is close to 48%, very similar to the Asia-Pacific region, but there is also variability between countries. For example, in adults, the highest rates, close to or above 80%, are reported for Guatemala (86.6%), Ecuador (85.7%), Colombia (83.1%), Nicaragua (83.3%), and Venezuela (81.3%), whereas considerably lower rates are reported for Brazil (39.6%) and Peru (63.0%). Prevalence in Mexico falls within the intermediate-high range, at 70.5% (see Statement 2). Such contrasts highlight the need for specific national prevention and control strategies, based on local epidemiology.

It should be emphasized that the choice of diagnostic method significantly impacts estimates on the prevalence of H. pylori.9 Studies utilizing serologic tests report a higher prevalence (53.2%; 95% CI 49.8–56.6), compared with those that employ methods detecting active infection, such as the urea breath test (43.9%), histology (37.4%), stool antigen testing (42.0%), or the rapid urease test (31.9%).8 This discrepancy arises because serology (IgG antibodies) cannot distinguish active from past infections, which may lead to an overestimation of the actual infection burden. Those findings underscore the need for standardizing diagnostic methods in epidemiologic studies and taking the differences into account when interpreting and comparing results between populations or temporal trends.

Globally, there are minimal differences in the prevalence of H. pylori between men and women, with nearly identical rates, according to the available data.7,8 However, cultural, socioeconomic, and environmental exposure factors may produce local variations that warrant further analysis.

- 2

Regions with low socioeconomic levels and poor sanitary conditions have a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A

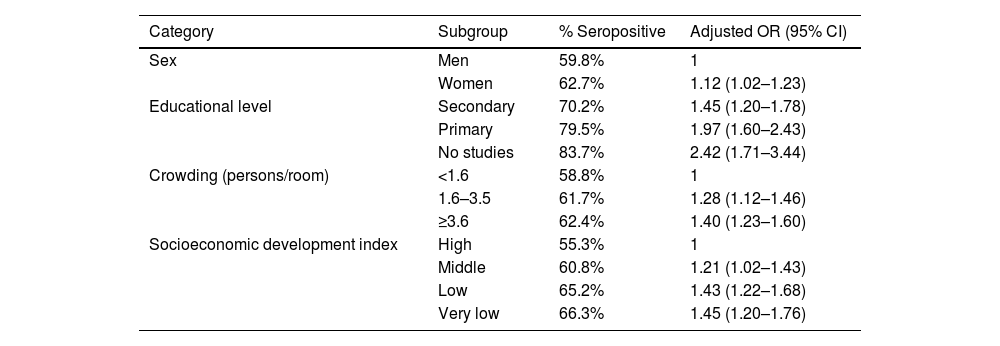

Regional variability reflects disparities in sanitary conditions, socioeconomic level, and access to effective treatments in different parts of the world. Low and middle-income countries have a significantly higher prevalence of H. pylori, estimated at 52.8% (95% CI 50.4–55.2), compared with high-income countries, where prevalence is 46.1% (95% CI 43.3–49.0).8 Similarly, regions with limited access to universal healthcare –classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) at coverage levels 2 and 3, indicating limited or moderate access to essential public health and basic medical care– report a prevalence of 59.8% (95% CI 50.1–69.6). In contrast, countries with broader coverage (level 5, health systems consolidated to provide basic services to a wide population) have a lower prevalence of 44.9% (95% CI 42.2–47.5). Greater prevalence of H. pylori infection has also been shown in populations exposed to deficient sanitary conditions, such as unclean drinking water.10,11 The impact of social determinants on H. pylori epidemiology is described in a study on a Chilean population that reported a significant reduction of 36% in the prevalence of H. pylori infection between the periods of 1995–2003 and 2010−2020.12 Notably, the reduction was not associated with mass eradication interventions, but rather with improved sanitary conditions, particularly greater access to clean drinking water and the implementation of wastewater treatment plants. Said study underlines how advances in basic infrastructure may have a substantial effect on reducing H. pylori transmission, especially in urban contexts, factors associated with seroprevalence of H. pylori in the Mexican population13 (Table 2).

- 3

Approximately two-thirds (70.5%) of the Mexican population is currently estimated to have H. pylori infection.

Socioeconomic factors and sanitation conditions that influence the prevalence of H. pylori infection.

| Category | Subgroup | % Seropositive | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 59.8% | 1 |

| Women | 62.7% | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | |

| Educational level | Secondary | 70.2% | 1.45 (1.20–1.78) |

| Primary | 79.5% | 1.97 (1.60–2.43) | |

| No studies | 83.7% | 2.42 (1.71–3.44) | |

| Crowding (persons/room) | <1.6 | 58.8% | 1 |

| 1.6–3.5 | 61.7% | 1.28 (1.12–1.46) | |

| ≥3.6 | 62.4% | 1.40 (1.23–1.60) | |

| Socioeconomic development index | High | 55.3% | 1 |

| Middle | 60.8% | 1.21 (1.02–1.43) | |

| Low | 65.2% | 1.43 (1.22–1.68) | |

| Very low | 66.3% | 1.45 (1.20–1.76) |

Adapted from Torres et al.14

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A

According to the largest epidemiologic study conducted in Mexico during the 1980s, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the general population was 66%, with a clear age-dependent pattern: in adults 25 years old or older, prevalence reached up to 80%.14 Based on that study, the same research group developed a modified catalytic exponential model utilizing hierarchical modeling to calculate infection probability over time.15 From those analyses, 85.9% of the Mexican population was estimated to be susceptible to H. pylori infection (IC 95% CI 84.3–87.5), reflecting a high percentage of individuals at risk for acquiring the infection during their lifetimes.

However, in the period from 2010 to 2022, the estimated prevalence in Mexican adults was 70.5% (95% CI 56.3–81.6) and 48.5% (95% CI 28.4–69.1) in the pediatric population.7,16–22 The apparent decrease in the prevalence of H. pylori in Mexico over the past decade could be related to improved living conditions, but also to the quality and heterogeneity of the few epidemiologic studies conducted during that period of time (n = 8). In general, the available Mexican studies utilize varying methodologies, employ different types of diagnostic tests, have small sample sizes, and have poor national representativeness. Likewise, they do not tend to address the differences between urban and rural populations, or the possibility of regional variability between states. This lack of uniformity and the absence of comprehensive data make it difficult to reach firm conclusions on current trends, underscoring the need for well-designed studies that differentiate active infection from previous exposure and adequately evaluate the sociodemographic and geographic factors associated with the infection.

- 4

Over the past decade, the annual recurrence, recrudescence, and reinfection rates due to H. pylori in Mexico are 9.3%, 2.3%, and 7%, respectively.

In complete agreement 91.7%, in partial agreement 8.3%

Quality of evidence: B

In the context of H. pylori infection, recurrence generally describes the reappearance of the bacterium after apparent eradication, without initially distinguishing between recrudescence or reinfection, especially in the absence of genetic typing. Recrudescence refers to the reappearance of infection by the same original strain due to treatment failure. It tends to present during the first 12 months and is often linked to antibiotic resistance, poor treatment adherence, or inadequate regimens. In contrast, reinfection implies new infection from a different H. pylori strain, after confirmed eradication. It tends to occur after the first year and is more frequent in regions with high prevalence and poor sanitary conditions. Distinguishing between the two scenarios is essential for correctly interpreting therapeutic results, adjusting clinical strategies, and having a better understanding of the epidemiologic dynamics of the infection.

Evidence produced in Mexico over the past decade is limited, but according to a study conducted by Sánchez-Cuén et al. on 128 patients with a previous diagnosis of H. pylori infection, 12 patients (9.3%) presented with an annual recurrence of the infection and were distributed into a 7% reinfection rate (nine patients) and a 2.3% recrudescence rate (three patients).23 Upon analyzing the presence of bacterial virulence genes, the recrudescence rate was 3.3% (1/30) in patients infected with strains that were positive for cytotoxin A-related antigen (CagA) and 1.8% (2/112) in patients with strains that were positive for vacuolizing A antigen (VacA). The reinfection rates were 10% (3/30) and 5.3% (6/112) for CagA and VacA, respectively. Those results suggest that recurrence and its components —recrudescence and reinfection— may be influenced by specific bacterial factors, emphasizing the relevance of genotyping in the post-treatment follow-up.23

A study conducted in 2003 by Leal-Herrera et al.24 produced contrasting results. Those authors documented a cumulative recurrence rate of 22.7% over a 24-month follow-up period. The study included 141 Mexican patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms treated at a referral hospital in Mexico City (40 children and 101 adults), all with eradication confirmed through a breath test after standard triple therapy. A significant number of cases (28.1%) corresponded to transient reinfections that resolved spontaneously, suggesting intense environmental exposure immediately after treatment. In addition, in the cases that underwent genotyping of the strains before and after recurrence, 75% corresponded to true reinfections and only 25% to recrudescence, reinforcing the notion that, in certain populations, particularly in adults, reinfection is a frequent and complex phenomenon, often associated with multiple strains. Those discrepancies likely reflect differences in diagnostic methodology, follow-up duration, and the epidemiologic and socioenvironmental conditions of each cohort, as well as genetic variations of the circulating strains.

- 5

Based on the evidence available in Mexico over the past decade, there has been an increase in antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori strains.

In complete agreement 83.3%, in partial agreement 16.7%

Quality of evidence: A

The antibiotic resistance of H. pylori is currently one of the main challenges for achieving effective treatment. Eradication regimen efficacy largely depends on the bacterial susceptibility of the antimicrobials employed. The growing resistance to key antibiotics, such as clarithromycin, metronidazole, and fluoroquinolones, has significantly reduced standard triple therapy success rates. Said resistance, driven by indiscriminate antibiotic use and the lack of systematic microbiologic surveillance, highlights the need for adapting therapies to local resistance patterns.

A recent global study (July 2025), representing 31 countries across six continents, evaluated key aspects related to the management of H. pylori-associated resistance to antibiotics. The results showed that resistance to the most widely used antibiotics in H. pylori eradication regimens is rising worldwide, with clarithromycin and levofloxacin resistance above 15% in 24/31 and 18/31 countries, respectively. Amoxicillin continues to be the exception, with resistance rates below 2% in 14 countries, albeit rates above 90% have been reported in some African countries.25

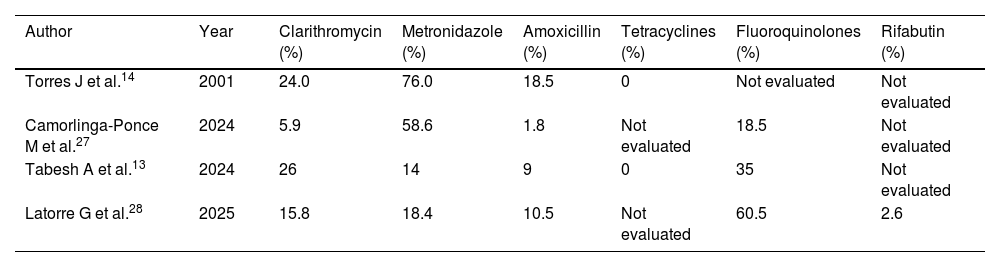

In Mexico, studies report antibiotic resistance variability, which may be attributed to methodological, geographic, and temporal differences. Resistance to metronidazole has been reported as high, with figures reaching 76% in older local studies,26 whereas it was reported at 18% in a recent multicenter study.3 For clarithromycin, a key antibiotic in triple therapies, resistance reaches 24%, a value situated above the threshold established by international guidelines for restricting its empiric use.27 Resistance to amoxicillin, although traditionally considered low, has been reported at between 1.8 and 10.5%, whereas the resistance rate for fluoroquinolones is high (60.5%), limiting its usefulness in rescue regimens (Table 3).26,27 Resistance to rifabutin has been less frequent, ranging from 2 to 6%. Resistance to more than one antibiotic is reported at between 29.6 and 56.3% of isolates, and 2.6–13.2% are resistant to three or more antibiotics. These data highlight the growing presence of multiresistant strains and the need for guiding treatment based on local susceptibility testing.26,27

Antimicrobial resistance rates.

| Author | Year | Clarithromycin (%) | Metronidazole (%) | Amoxicillin (%) | Tetracyclines (%) | Fluoroquinolones (%) | Rifabutin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torres J et al.14 | 2001 | 24.0 | 76.0 | 18.5 | 0 | Not evaluated | Not evaluated |

| Camorlinga-Ponce M et al.27 | 2024 | 5.9 | 58.6 | 1.8 | Not evaluated | 18.5 | Not evaluated |

| Tabesh A et al.13 | 2024 | 26 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 35 | Not evaluated |

| Latorre G et al.28 | 2025 | 15.8 | 18.4 | 10.5 | Not evaluated | 60.5 | 2.6 |

Thus, regimens based on clarithromycin or fluoroquinolones are suboptimal as first-line treatment in Mexico. Even though metronidazole also shows high in vitro resistance, it is still clinically effective when used in quadruple therapies, particularly in concomitant regimens or those that include bismuth.

- 6

In Mexico, the prevalence of H. pylori strains positive for the CagA gene varies from 40 to 80%.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A

H. pylori expresses different virulence factors that determine its capacity to colonize the gastric mucosa, evading the host’s immune response and causing tissue damage. CagA stands out for its strong association with intense gastric inflammation, peptic ulcer, and gastric adenocarcinoma. VacA, biofilm-associated protein A (BapA), outer inflammatory protein A (OipA), and the induced by contact with epithelium A (IceA) also play an important role in H. pylori pathogenesis, by facilitating bacterial adhesion, inducing cell damage, and modulating the inflammatory response.29

In Mexico, as in other Latin American populations, a high prevalence of CagA-positive strains has been reported, which could be related to the genetic evolution of the circulating strains, as well as to local environmental and epidemiologic factors. In different studies conducted in Mexico, CagA gene-carrying H. pylori strains, particularly the combined VacA s1m1/CagA genotype, are the most frequent (44.8%–81.3%) in biopsy samples from both the gastric antrum and body. A recent study confirmed said trend, with a 70.7% prevalence of that genotype in cases of chronic gastritis, 57.9% in gastric ulcer, and 81.3% in patients with gastric cancer.30–34 Similarly, previous studies conducted in southern Mexico have reported frequencies of CagA at 71.1 and 69.7%.31,32 Those findings indicate that the CagA gene is clearly predominant in the Mexican population and its high prevalence could be related to the greater severity of the clinical manifestations seen in the region.

Indications- 7

H. pylori eradication is indicated in patients with active or previous peptic ulcer because it significantly reduces ulcer recurrence and associated complications.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

An analysis that included 55 clinical trials reported that, in duodenal ulcer healing, eradication therapy was superior to ulcer-healing drugs (UHDs) (34 studies, 3,910 patients, relative risk (RR) of persistent ulcer = 0.66, 95% CI 0.58−0.76) and no treatment (two studies, 207 patients, RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.26−0.53). No significant differences in gastric ulcer healing were detected between eradication therapy and UHDs (15 trials, 1,974 patients, RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.90–1.68). In duodenal ulcer recurrence prevention, there were no significant differences between eradication therapy and UHD maintenance (four trials, 319 patients, RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.42–1.25), but eradication therapy was superior to no treatment (27 trials, 2,509 patients, RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.15−0.26). In gastric ulcer recurrence prevention, eradication therapy was superior to no treatment (12 trials, 1,476 patients, RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.22−0.45).35

Another meta-analysis that included 401 patients showed that H. pylori eradication significantly reduced the incidence of peptic ulcer recurrence at 8 weeks (RR 2.97; 95% CI 1.06–8.29) and one year (RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.10–2.03) after surgical intervention.36 A study that included 66 patients with peptic ulcer bleeding and H. pylori infection, showed that H. pylori eradication was associated with a significant decrease in ulcer recurrence (2.4% vs. 62.5%; RR 0.04; 95% CI 0.01−0.17) and rebleeding (0% vs. 37.5%; RR 0.06; 95% CI 0.01−0.45).37 In a randomized trial that included 99 patients with H. pylori infection, the patients who received specific eradication treatment had a significantly lower ulcer recurrence rate at one year, compared with those who only received omeprazole (4.8% vs. 38.1%).38

- 8

H. pylori eradication is indicated in patients with low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

A multicenter trial that included 84 patients with stage EI low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, reported complete remission in 81% of the patients after H. pylori eradication.39 A systematic review of 32 studies that included 1,408 patients found a remission rate of 77.5%, with higher rates in stage I than in stage II(1) lymphoma (78.4% vs. 55.6%) and in Asian populations, compared with Western ones (84.1% vs. 73.8%).40 A pooled analysis of 34 studies, with 1,271 patients, reported an overall remission rate of 77.8%, after successful H. pylori eradication.41 More recently, a retrospective study, with 63 patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, reported complete remission of the lymphoma in 81% of the patients, in 18 months.42 Lastly, a meta-analysis on the efficacy of H. pylori eradication as the sole initial treatment in patients with early-stage gastric MALT lymphoma showed a 75.18% complete histologic remission rate after eradication (95% CI 70.45%–79.91%). That evidence supports the current recommendation of H. pylori eradication as first-line treatment in patients with stage EI and EII(1) MALT lymphoma, given its potential for inducing tumor regression with no need for additional oncologic treatment in most cases.43

- 9

In patients with symptoms suggestive of dyspepsia (with no alarm features) and a positive H. pylori test, eradication therapy is recommended because it improves dyspeptic symptoms.

In complete agreement 79.2%, in partial agreement 16.7%, uncertain 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

A meta-analysis of 14 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) showed that H. pylori eradication significantly improved dyspeptic symptoms, compared with controls. The odds ratio (OR) for symptom improvement was 1.38 (95% CI 1.18–1.62) with low heterogeneity (I² = 51.8%).44 Another meta-analysis that included 25 RCTs, with 5,555 patients, found that H. pylori eradication therapy had a pooled RR of 1.23 (95% CI 1.12–1.36) for symptom improvement. The long-term follow-up (≥1 year) showed significant benefit (RR 1.24; 95% CI 1.12–1.37).45 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on 158 patients with functional dyspepsia and H. pylori infection, showed that eradication led to significant dyspepsia symptom improvement (41.77%; 95% CI 30.77−053.41), compared with placebo (18.99%; 95% CI 11.03–29.38).46

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled HEROES study that included 404 patients with functional dyspepsia (Rome III) found that 49% of the patients in the eradication group achieved at least 50% symptom improvement at 12 months, compared with 36.5% of the controls (p = 0.01), with a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 8.47 Another RCT with a similar patient group (n = 213) reported that only 91 patients completed the one-year follow-up. Upon comparing the dyspepsia response rate at one year, between the non-eradicated group (n = 24) and the eradicated group (n = 67), each showed the following results: complete response in 62.5% (non-eradication) vs. 62.7% (eradication), satisfactory response (≥50%): 0% vs. 19.4%, partial response (<50%): 1.25% vs. 11.9%, and refractoriness: 25.0% vs. 6.0%, respectively. The multivariate analysis showed that H. pylori eradication (OR 5.81; 95% CI 1.07–31.59) and symptom improvement at three months (OR 28.90; 95% CI 5.29–157.82) were associated with improved dyspepsia at one year.48

In summary, H. pylori eradication in patients with dyspeptic symptoms and positive (non-serologic) tests, with no alarm symptoms, is supported by evidence indicating significant symptom improvement. Nevertheless, there are no Mexican studies on the topic, and considering the high NNT, conducting such studies is recommended.

- 10

In patients who require chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) use, and who are infected with H. pylori, eradication therapy is recommended for reducing the risk of acid peptic disease and its complications.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

The significantly increased risk of acid peptic disease is 61.1 times higher in patients with H. pylori infection and NSAID use than in patients with no H. pylori infection and no NSAID use.49 In population studies, chronic NSAID use in patients with H. pylori infection has been documented to increase the risk of developing acid peptic disease, with an OR of 2.73. Likewise, H. pylori eradication reduces the risk of recurrence of peptic ulcer disease in chronic NSAID users, whereas non-eradication increases the risk (OR 1.24).50

Case-control studies have identified age >75 years (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.3–4.2) and H. pylori infection (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.5) as major factors for developing gastric mucosal lesions, and antisecretory agent use is protective (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.28−0.99).51

H. pylori infection has been reported to cause an increase in neutrophils in the gastric mucosa. Patients with H. pylori infection who also take NSAIDs have been shown to have a higher incidence of ulcerations, compared with patients with H. pylori infection, but who have no neutrophil infiltration into the gastric mucosa. Said gastric neutrophilia appears to be an important factor.52 Neutrophil infiltration is one of the factors associated with acid peptic disease in patients who take NSAIDs and are infected with H. pylori. Other factors that have been described are previous NSAID exposure, a history of peptic ulcer, and no antisecretory therapy.53

Eradication therapy before starting treatment with NSAIDs has also been shown to significantly reduce the risk of complications. A RCT reported that 3% of patients with H. pylori eradication presented with peptic complications related to NSAIDs, compared with 26% of the patients who had not achieved eradication.54 Another study showed that in patients with long-term NSAID use, H. pylori eradication reduced the risk of ulcers from 34.4 to 12.1% at six months.55 However, other studies have shown that eradication did not result in a decrease of bleeding ulcers at six months, in patients with chronic NSAID use.56 In addition to H. pylori infection, age and a history of ulcers are relevant risk factors. Given the association between H. pylori and NSAID-related lesions, we recommend eradication treatment in patients with chronic NSAID use, to reduce the risk of complications.

- 11

In patients with unexplained iron deficiency anemia and H. pylori infection, eradication treatment is indicated, as it may improve hemoglobin and ferritin levels.

In complete agreement 83.3%, in partial agreement 12.5%, uncertain 4.2%

Quality of evidence: B; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

H. pylori eradication in patients with iron deficiency can optimize certain parameters related to iron kinetics. However, the effects on iron deposits may vary. The decrease of iron levels in patients with H. pylori infection may be associated with chronic gastritis and achlorhydria induced by long-standing infection. Such achlorhydria can interfere with the absorption of dietary iron, contributing to the deficiency seen in those patients.57 Studies indicate that patients with H. pylori infection do not respond to oral iron supplementation, supporting the malabsorption hypothesis.58 Patients with chronic gastritis due to H. pylori may have elevated levels of gastric lactoferrin, which captures iron from transferrin. An increase in hepcidin, related to anemia in animal and human models, has also been observed.59

Epidemiologic studies that measure antibodies against H. pylori have demonstrated that seropositivity is associated with reduced ferritin levels (<30 µg/l) (OR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–1.8).60 Active infection has been linked to iron deficiency anemia in children.61 Finally, studies show that eradicating H. pylori in patients with iron deficiency, without supplementation, increases iron, transferrin saturation, and hemoglobin levels six months after eradication. No increase in ferritin was observed.62 There is biologic plausibility between infection and iron deficiency, supported by studies showing said association. The eradication of the infection may improve iron levels; thus, we recommend proceeding with eradication.

- 12

In patients diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and confirmed H. pylori infection, eradication therapy is recommended as part of therapeutic management, as it may significantly contribute to increasing the platelet count and improve clinical outcomes.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: B; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

In patients who present with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, H. pylori eradication may increase the platelet count in a substantial number of patients. Pathophysiologically, this increase may be explained by a greater pathologic capacity of monocytes in H. pylori-infected patients, due to a decrease in the inhibitory Fc gamma IIB receptor (FcγRIIB). By eradicating the H. pylori, the pathologic capacity of the monocytes is normalized, improving autoimmunity against the platelets. Said phenomenon has been observed in studies on humans, as well as on animal models.63

H. pylori eradication has been shown to improve platelet counts in 44.7% of patients, with an increase from 57.3 ± 28.1 × 109/l to 104.6 ± 37.4 × 109/l. No improvement was seen in patients in whom eradication failed.64 The increase in platelet count was found to be beneficial in follow-up studies, with one-half of the patients having a short-term response and the other half, up to seven years.65 Response may vary by geographic region. Some studies have reported lower platelet responses after successful H. pylori eradication, mainly in low prevalence areas.66 The lower response rate in pediatric patients suggests potential differences in pathophysiology, compared with adults.67

H. pylori eradication in patients with confirmed infection and idiopathic purpura is generally recommended, given its potential to significantly improve platelet counts in a substantial number of patients. However, response may vary, according to individual and regional factors, and not all patients may benefit equally.

- 13

In individuals with first-degree relatives with gastric cancer and confirmed H. pylori infection, eradication of the bacterium is recommended.

In complete agreement 91.7%, in partial agreement 8.3%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Chronic H. pylori infection and secondary changes in the gastric mucosa, known as the Correa cascade (chronic gastritis, atrophy, metaplasia, dysplasia, cancer), are responsible for 90% of gastric adenocarcinomas worldwide.68H. pylori eradication is reported to reduce the risk for gastric cancer in first-degree relatives. In a recent meta-analysis, there was a 34% reduction in the incidence of gastric cancer (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.49−0.89) after eradication, with a greater benefit observed in Asian populations and in individuals with no preneoplastic lesions.69

H. pylori eradication has also been associated with a 20–70% reduction in the frequency of metachronous tumors in individuals with previous gastric resection.70 Around 10% of gastric cancer cases show familial aggregation, with multiple contributing factors, leading to a two to 10-times increase in the risk for the development of gastric cancer in first-degree relatives of the infected individual, and they appear to act synergically. Said factors include genetic predisposition, infection due to H. pylori and its strains, and shared environmental factors, such as diet. Thus, H. pylori eradication is considered essential as primary prevention in that high-risk group, with the greatest benefit in patients with no premalignant lesions, underscoring the importance of early intervention.71–73

Some Asian guidelines (from populations with a high prevalence of gastric cancer) suggest starting H. pylori detection and treatment in individuals between 20 and 40 years of age, given that eradication has demonstrated greater effectiveness as prevention, in the absence of premalignant lesions (atrophy and/or metaplasia).74 In contrast, a recent Western clinical practice guideline (from low-to-intermediate risk regions) on screening and surveillance in subjects at high risk of gastric cancer proposes starting screening at 45 years of age, or earlier if there are numerous risk factors, or individualize screening to begin 10 years before the age of diagnosis of the index case. It even suggests combining upper endoscopy and colonoscopy for detecting colon cancer, to optimize resources.75,76

In low-to-average risk populations (as in Mexico), noninvasive tests may be carried out for detecting H. pylori, and if positive, endoscopy may be performed. Since positive patients are considered high-risk, high-quality endoscopy and structured surveillance are recommended, given that malignant and/or premalignant lesions cannot be identified through noninvasive tests for H. pylori.73

A prospective, double-blind Korean trial demonstrated that treatment of H. pylori infection reduced the incidence of gastric cancer by 55% in 832 first-degree relatives of Korean patients with gastric cancer versus 844 untreated individuals. When analyzed through eradication confirmation, there was a 73% decrease in risk, at 9.2 years of follow-up (incidence of 0.8% vs. 2.9%).72

- 14

H. pylori eradication is indicated in patients with atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia because it can halt or delay progression to dysplasia or gastric cancer.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

The main strategy for primary prevention of gastric cancer is H. pylori eradication, and the greatest benefit is achieved when no premalignant conditions have yet developed.70 However, eradication of the bacterium in the presence of premalignant lesions (atrophy/metaplasia) is very useful and is part of the treatment recommendations, in addition to endoscopic surveillance, given that it can delay or prevent disease progression.76,77

First-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer and patients with specific hereditary syndromes should be considered for premalignant lesion screening through high-quality endoscopy.76 Endoscopic examination to detect premalignant lesions should be performed with high definition and magnification imaging and biopsies should be systematically taken (updated Sydney protocol): five biopsies, two from the antrum, two from the body, and one from the incisura, placed in separate containers, with photo-documentation of at least six sites.78

Histopathologic reports should include the presence of gastric atrophy and/or intestinal metaplasia and its extension, severity, metaplasia subtype (complete/incomplete), and the presence or absence of H. pylori, as said factors are clearly associated with progression and/or regression of premalignant conditions. The operative link for gastritis assessment and gastric intestinal metaplasia (OLGA/OLGIM) scores are useful for that purpose, and advanced stages (III/IV) are strongly associated with progression to gastric cancer.79,80

The eradication of H. pylori in the presence of mild and limited gastric atrophy/intestinal metaplasia may halt the progression or even induce the histologic regression of those conditions, as demonstrated in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on the 20-year experience of a Colombian cohort and a Mexican study carried out in Chiapas, involving 248 individuals.81,83 The management of those conditions includes H. pylori eradication and endoscopic surveillance with biopsy sampling. The suggested surveillance interval is every three years in the following cases76: extensive and/or incomplete intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, a family history of gastric cancer in a first-degree relative, and demographics (patients from regions of high incidence), as well as individuals with OLGA/OLGIM III/IV. Patients with this last factor have a 20-times greater risk for progression to gastric cancer and are the least susceptible to regression with H. pylori eradication.82,84

- 15

Eradication therapy is recommended in patients infected with H. pylori who require long-term PPI use.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: B; Strength of the recommendation: Weak, in favor of

It is important to remember that there are few indications for chronic PPIs use, such as gastroprophylaxis in patients at high risk of gastroduodenal ulcer recurrence who have persistent risk factors. Thus, before considering eradication therapy in that context, the need for chronic PPI use, or not, should be carefully reviewed. For patients with a legitimate indication for chronic PPI use, the rationale for H. pylori eradication is based on experimental evidence and cohort studies on humans that have shown that chronic PPI use induces inflammatory changes in the oxyntic mucosa that gradually produce atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia.85–87 The metaplastic chronic gastritis that predominates in the gastric body is considered a risk factor for the development of non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma and there is evidence that the pre-existing inflammatory alterations in the gastric body progress more rapidly in subjects with H. pylori who receive long-term PPI therapy.88,89

Other factors, such as colonization of the stomach by organisms other than H. pylori or bile acid alterations caused by a more alkaline pH, also induce inflammatory changes that contribute to increasing the remodeling processes of the gastric mucosa. Nevertheless, despite the evidence of a synergistic effect of PPIs and H. pylori infection on gastric acid secretion, their causal relationship and the development of cancer is still a subject of debate.90 At any rate, those pathophysiologic mechanisms should be mitigated in patients who require long-term PPI use, which further supports prudent PPI use, following clinical practice guidelines.91

The fact that the risk for developing gastric cancer persists in some patients with chronic metaplastic gastritis despite having undergone successful H. pylori eradication treatment should be kept in mind, emphasizing the need for establishing a structured surveillance strategy in such cases.76

- 16

H. pylori eradication is indicated in patients who have undergone surgical or endoscopic resection of gastric cancer because it significantly reduces the risk for cancer recurrence and may improve the long-term prognosis.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Currently, the only curative treatment for gastric adenocarcinoma is surgical or endoscopic resection of the incipient neoplastic lesions. The preneoplastic conditions, i.e., atrophy, metaplasia, and dysplasia, persist in those patients, elevating the risk for metachronous lesions. Thus, they are candidates for receiving eradication treatment, even with no confirmation of active H. pylori infection. This treatment strategy is supported by controlled studies conducted in several Asian countries.92,93

A systematic review and meta-analysis that included 6,967 patients demonstrated a significant decrease in gastric cancer-related mortality in patients who received successful eradication treatment for H. pylori (OR 0.47; 95% CI 0.33−0.67). Improvement in both gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia was also demonstrated.94 It should be emphasized that, even after successful H. pylori eradication, long-term follow-up programs are essential.76

- 17

Eradication therapy is recommended in patients who take warfarin or direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and have concomitant H. pylori infection.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: C; Strength of the recommendation: Weak, in favor of

The use of vitamin K antagonists (e.g., warfarin) or direct-acting oral anticoagulants, such as dabigatran (an activated factor II or thrombin inhibitor) and rivaroxaban or apixaban (activated factor X inhibitors) increases the risk of nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding.95 Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding have been identified in warfarin users, such as age >65 years, INR > 2.1, cirrhosis of the liver, and a previous history of bleeding.96 In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), the incidence of bleeding per 100 patients/year for warfarin is 2.87 (95% CI 2.41–3.41), for dabigatran is 2.29 (95% CI 1.88–2.79), and for rivaroxaban is 2.84 (95% CI 2.30–3.52). In patients with no AF, incidence is 3.71 (95% CI 2.16–6.40), 4.10 (95% CI 2.47–6.80), and 1.66 (95% CI 1.23–2.24), respectively, and is higher in adults above 76 years of age.97 The risk increases if the patient also takes NSAIDs, ASA, or other antiplatelet agents, and is lower if the patient uses PPIs.98,99

There is less evidence associating gastrointestinal bleeding with H. pylori-infected patients who take anticoagulants. An increased risk has not been demonstrated in some cohort studies,100 whereas others suggest it may be a risk factor.101 Because H. pylori is one of the two main risk factors for developing peptic ulcer, with a lifetime risk for duodenal ulcer of 18.4 and 2.9 for gastric ulcer in CagA-producing strains, any potential risk factor the patient could have that increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding should be tested for and eradicated.68,102

- 18

H. pylori infection should be investigated in patients with peptic ulcer and active bleeding.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Patients with peptic ulcer, regardless of the cause, are at an increased risk for bleeding.103H. pylori has a prevalence of 20–50% in patients with peptic ulcer-associated bleeding, and two studies have identified H. pylori infection as an independent risk factor for recurrent bleeding due to peptic ulcer in their multivariate analyses, with an additive effect if ASA or NSAIDs are used.104,105

In addition to standard treatment for bleeding control and cure through acid suppression with PPIs or PCABs, and/or endoscopic treatment, secondary preventive measures include suspending or minimizing any additional risk, i.e., temporary suspension of NSAIDs, ASA, and anticoagulants. If discontinuation is not feasible, indefinite use of gastric antisecretory agents and H. pylori testing and eradication should be considered. The rebleeding recurrence rate in H. pylori-associated ulcers with no other risk factors is 11.2–26%.103,106 Several studies have reported a decrease in bleeding and recurrence rates after eradication therapy, as well as superiority over antisecretory treatment alone.107,108

The most appropriate time for eradication therapy is still a subject of debate, but it may be started as soon as oral intake is restored after bleeding control.109 A study compared bleeding and recurrence rates and reported that an eradication delay >120 days was associated with a higher risk (RR 1.52) for complicated ulcers.110 The factors associated with bleeding and ulcer recurrence after eradication therapy are the size and number of ulcers, as well as coagulation function.111

- 19

When patients request screening and treatment for H. pylori infection, individualized assessment of benefits and risks is appropriate, in accordance with the Latin American and Caribbean Code Against Cancer.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: C; Strength of the recommendation: Weak, in favor of

Patients have the right to request screening and treatment for H. pylori, due to the association with gastric cancer, as outlined in Statement 12 of the Latin American and Caribbean Code Against Cancer.112 This code, convened by the International Agency on the Research of Cancer (IARC) of the WHO and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and developed by specialists in the field, promotes actions that individuals can take for helping prevent cancer.

H. pylori is classified by the IARC as a group 1 carcinogen, signifying that there is conclusive evidence on its causal role in human cancer.113 As mentioned previously, H. pylori is associated with MALT lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma because it produces the CagA oncoprotein that alters the signaling pathways involved in the process of carcinogenesis.114 Progression to cancer in infected individuals depends on host-related and environmental factors, such as smoking, alcohol use, overweight, a family history, and certain hereditary conditions, all of which should be personally discussed with the patient.

Likewise, the different screening methods available should be explained, selecting the one best suited to the patient’s characteristics and local healthcare policies. Primary prevention of gastric cancer consists of testing for and eradicating H. pylori, which has been shown to decrease the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer.115

The Working Group of the IARC, in collaboration with the WHO, recently issued a technical guideline that supports the implementation of population-level screen-and-treat strategies for H. pylori as a primary prevention measure for gastric cancer. This recommendation applies to countries with an intermediate-to-high incidence of gastric cancer (≥10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year) and underlines the need for adapting their implementation to local epidemiologic conditions. Even though Mexico does not meet this criterion nationally, there are signs of regional variability that could justify targeted strategies. However, there are still no studies that clearly define the areas of Mexico with greater incidence or risk, making it a priority for guiding future risk-based prevention policies.

- 20

H. pylori has no causal role in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, patients with H. pylori infection and confirmed GERD require eradication treatment.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: C; Strength of the recommendation: Weak, in favor of

H. pylori infection is not associated with the development of erosive esophagitis and has no protective effect against GERD. Likewise, eradication of the microorganism has no impact on the exacerbation of GERD.116

In a study with 171 patients, the relation between histologic and topographic characteristics of H. pylori gastritis and the presence and severity of esophagitis in patients with reflux symptoms was evaluated. The bacterium was detected in 75% of the patients with GERD and in 69% of the patients without reflux. There were no statistically significant differences between groups regarding the presence or grade of esophagitis.117

A retrospective analysis that included 340 patients, compared the length of Barrett’s esophagus, according to the Prague criteria, and the presence of esophagitis before and after eradication therapy. Reflux esophagitis was identified in 2% of the patients before eradication and 6% after eradication, which was a significant increase (p = 0.007). Barrett’s esophagus was present in 20% before eradication, with a median length of C0M1. Elongation after treatment was observed in only 0.6%. Those authors concluded that treatment of H. pylori had no significant impact on the development or elongation of Barrett’s esophagus.118

In patients with H. pylori infection, chronic PPI use may have an impact on the development of atrophy and/or intestinal metaplasia. Therefore, eradication is recommended in patients with long-term antisecretory therapy, such as the patients with GERD who require maintenance therapy. In conclusion, the presence of GERD should not influence the decision to carry out eradication therapy, when indicated.

Diagnosis- 21

In adult patients with suspected H. pylori infection, the 13C/14C-urea breath test has greater sensitivity and specificity than the stool antigen test, and therefore, is considered the preferred diagnostic option in patients with no alarm symptoms.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: B; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Noninvasive tests for detecting H. pylori include serology, stool antigen tests, and the carbon labeled 13C or 14C-urea breath test. The breath test is considered the noninvasive diagnostic method of choice for H. pylori due to its diagnostic sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 96%,108,119 which are required characteristics for minimizing the risk of false negatives. In contrast, the stool antigen test, although still useful, can be affected by different factors that reduce its effectiveness, the most relevant of which is the fecal bacterial load. The breath test is accessible and less invasive, compared with the stool antigen test, and has been shown to be useful in low-risk patients with no alarm features. In addition, it does not depend on the immune status of the patient and is suitable for both the initial diagnosis and eradication confirmation after treatment. Therefore, whenever available, we recommend the C13/C14- urea breath test as the option of choice for diagnosing H. pylori infection in adult patients with no alarm symptoms.120–122

- 22

Serologic tests are useful in epidemiologic studies. They are not recommended for diagnosing infection or corroborating H. pylori infection.

In complete agreement 87.5%, in partial agreement 12.5%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Serologic testing (detection of antibodies in blood) should only be utilized in screening for H. pylori infection and in epidemiologic studies, given that its main disadvantage is the inability to distinguish between current infection and previous exposure. Additionally, in recent H. pylori infection, antibody levels may not yet have reached detectable thresholds, considering that IgG antibodies typically appear approximately 21 days after infection and may persist for several months.123,124 However, in certain clinical situations (active gastrointestinal bleeding, atrophic gastritis, MALT, and gastric cancer), serologic tests may be used as the initial test for diagnosing H. pylori infection. In such cases, a second test for confirming H. pylori infection, either the stool antigen test or urea breath test, is always recommended.124 Serologic testing is also incorporated into broader diagnostic panels, such as the GastroPanel®,125 which combines IgG antibody detection against H. pylori with serum biomarkers of gastric function, including pepsinogen I, pepsinogen II, and gastrin-17. The GastroPanel enables the evaluation of the presence of H. pylori, gastric atrophy (antral or corporal), and the risk of gastric diseases, such as chronic atrophic gastritis or gastric cancer. Although it does not replace the breath test as the method of choice for detecting active infection, the GastroPanel may be useful in the context of broader gastric function evaluation or in population-based screening studies.

- 23

Confirmation of H. pylori infection eradication should be carried out through a noninvasive test. The C13/C14-urea breath test or stool antigen test are considered valid options and should be performed at least four weeks after completing eradication therapy.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Numerous consensuses and guidelines recommend that eradication be confirmed at least four weeks after completing the treatment regimen, through a noninvasive test. Valid options are the C13/C14-urea breath test and the stool antigen test.119,121 The urea breath test is the preferred method because of its high sensitivity and specificity (95–98% and 90–98%, respectively). It also has the advantage that its performance is not affected by recent antibiotic use.9,126 The stool antigen test may also be an option, but its sensitivity may be compromised by a low bacterial load. The implementation of noninvasive tests for confirming H. pylori eradication is essential for reducing the incidence of gastric diseases associated with persistent infection.121,127

- 24

Biopsy sampling following the Sydney protocol is recommended in patients undergoing endoscopy, with findings suggestive of H. pylori infection.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

The histopathologic analysis of gastric biopsy samples taken during an endoscopic procedure is useful for determining the presence of H. pylori and detecting premalignant gastric lesions, such as gastric atrophy, complete or incomplete intestinal metaplasia, low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, and even adenocarcinoma in situ.108,128,129 Biopsy samples should be taken, following the modified Sydney protocol,108,123,128,130 a standardized method that has shown a greater diagnostic yield for detecting H. pylori and premalignant lesions.108,128–130 Various studies have demonstrated that adherence to this protocol improves H. pylori detection, compared with random biopsy sampling (59.2% vs. 20.5%; OR: 5.7; 95% CI: 2.6–12.2),129 and when not followed, leads to missing 30% of premalignant lesions and 10% of H. pylori infections.130 Using one biopsy container for samples from the gastric body and another for samples from the antrum and incisura angularis is recommended, to aid the pathologist in staging the atrophy and intestinal metaplasia of each segment with the OLGA and OLGIM scales, respectively.131

Alternatively, it has been suggested that in patients with gastric intestinal metaplasia (EGGIM 0), with endoscopic mild atrophy (Kimura–Takemoto C0-C2), whose procedure is performed by an experienced endoscopist, systematic biopsy sampling may be omitted, relying solely on the rapid urease test (when available), given the high probability of OLGA stage 0 in that context. Said strategy must still be validated before it can be generally recommended.

- 25

The Kyoto classification, based on mucosal and vascular patterns using image-enhanced endoscopy, has a high negative predictive value for H. pylori infection.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: B; Strength of the recommendation: Weak, in favor of

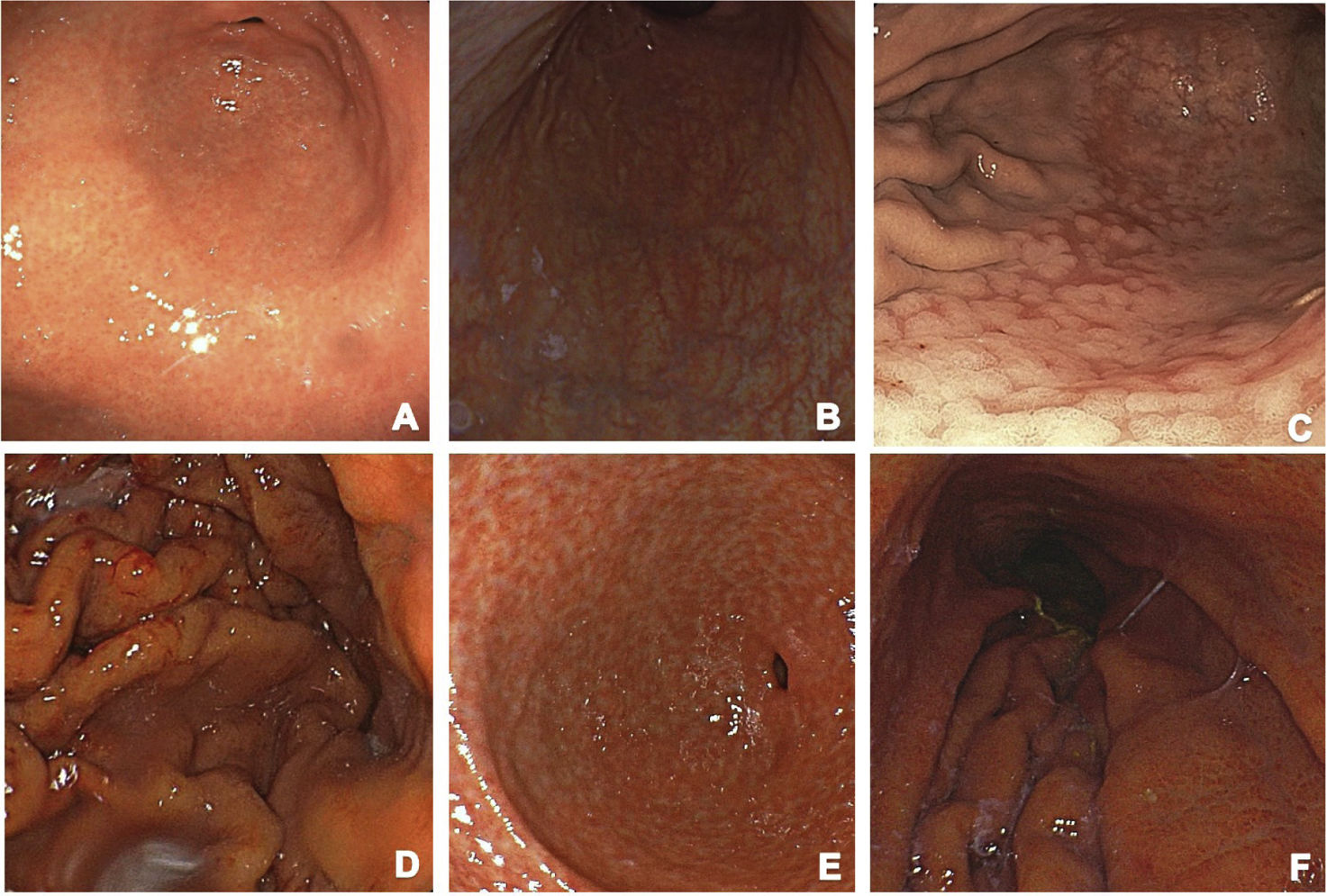

Altered mucosal patterns seen through high-resolution endoscopy may guide the diagnostic suspicion of H. pylori infection. The Kyoto classification provides a high negative predictive value (NPV) for detecting H. pylori infection through the description of the vascular and mucosal pattern, added to the fact that it is a predictive risk indicator for developing gastric cancer (Fig. 1A–F shows the endoscopic Kyoto classification). Gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and the regular arrangement of collecting venules are correlated with a low probability of infection, with a NPV above 90%.132,133 Enhanced-image endoscopy complemented with artificial intelligence increases diagnostic accuracy by enabling clearer visualization of those mucosal characteristics. The Kyoto classification offers a comprehensive approach by combining endoscopic findings with gastric cancer risk assessment, making it an essential tool in daily clinical practice134,135 (Fig. 1).

- 26

When endoscopic findings are consistent with H. pylori infection, the rapid urease test is considered a fast, easy-to-use, and accurate diagnostic method for detecting active infection.

Kyoto endoscopic classification: (A) Normal-appearing mucosa: regular folds and a healthy appearance. (B) Atrophic mucosa: notable thinning of the mucosa, gastric gland loss, and pale areas are observed, suggesting significant damage and a potential risk of malignancy. (C) Metaplasia: the mucosa has a rough appearance, indicating cellular changes that may be early signs of cancer development. (D) Prominent, thickened gastric folds: this finding is typical of active gastritis and may be associated with H. pylori. (E) Nodularity: raised or nodulous areas in the mucosa that are indicative of chronic inflammation and the risk of cancer. (F) Erythema: diffuse reddening of the mucosa, reflecting active inflammation and may be associated with the presence of H. pylori.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

The rapid urease test is an indirect method that evaluates the presence of the urease enzyme in a gastric biopsy sample. Its usefulness lies in its ability to detect active infection. When the gastric sample comes into contact with urease, the enzyme hydrolyzes urea, converting it into carbon dioxide and ammonia, producing a change in pH that is detected through a variation in color.123,136 The biopsy can be taken from the antrum or the gastric body or both. Reaction time depends on bacterial load and temperature. A positive result may appear within the first hour or up to 24 hours later.137 The sensitivity of the test varies from 88.5 to 95.6%, and its specificity varies from 84.2 to 100%.123 It has a 94% positive predictive value (PPV), a 100% NPV, and 98% diagnostic accuracy.138 False negatives may result from the use of antibiotics, bismuth, PPIs, or patient conditions, such as atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, or gastrointestinal bleeding. False positives are very rare and may be related to the presence of other urease-producing bacteria.139

- 27

Molecular techniques, such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are methods that enable the identification of the mutations involved in antibiotic resistance and are valuable for guiding targeted treatment.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Molecular techniques have revolutionized the diagnosis and treatment of H. pylori infection, by enabling the precise identification of the gene mutations associated with antibiotic resistance, which is crucial for selecting effective therapeutic regimens. The PCR test can detect specific resistance-conferring genes, such as those that encode the β-lactamase enzymes and other resistance mechanisms.139 On the other hand, NGS provides a thorough analysis of the H. pylori genome, enabling the identification of known mutations and the discovery of new variants associated with multidrug resistance. The genetic profile of the specific strain can be characterized through this approach, facilitating the implementation of targeted and personalized treatment.140–142

Zhang et al. evaluated the effectiveness of PCR testing and NGS for identifying the mutations related to antibiotic resistance and showed that the identification of mutations in key genes, such as GyrA and PonA, is directly related to lower eradication rates, compared with standard empiric treatment. This suggests that molecular testing may improve clinical results by enabling more targeted and personalized treatment approaches.143 In Latin American countries, including Mexico, Latorre et al.28 examined the antibiotic resistance of H. pylori utilizing NGS and found that a high percentage of the strains analyzed presented with mutations associated with resistance to multiple antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and clarithromycin (Table 3). Region-specific resistance patterns were identified through that approach. The findings suggest that the implementation of molecular testing could be useful in the decision to personalize treatment based on molecular profiles, improving eradication rates and reducing the incidence of treatment failure.28

However, in Mexico and similar settings, the availability and high cost of those molecular techniques —including PCR and NGS— currently limit their routine clinical application. With the ongoing advances in technology, greater personnel training, and progressive cost reduction, those tools are expected to become more accessible in the near future, enabling a more accurate and effective approach to H. pylori infection management in local contexts.

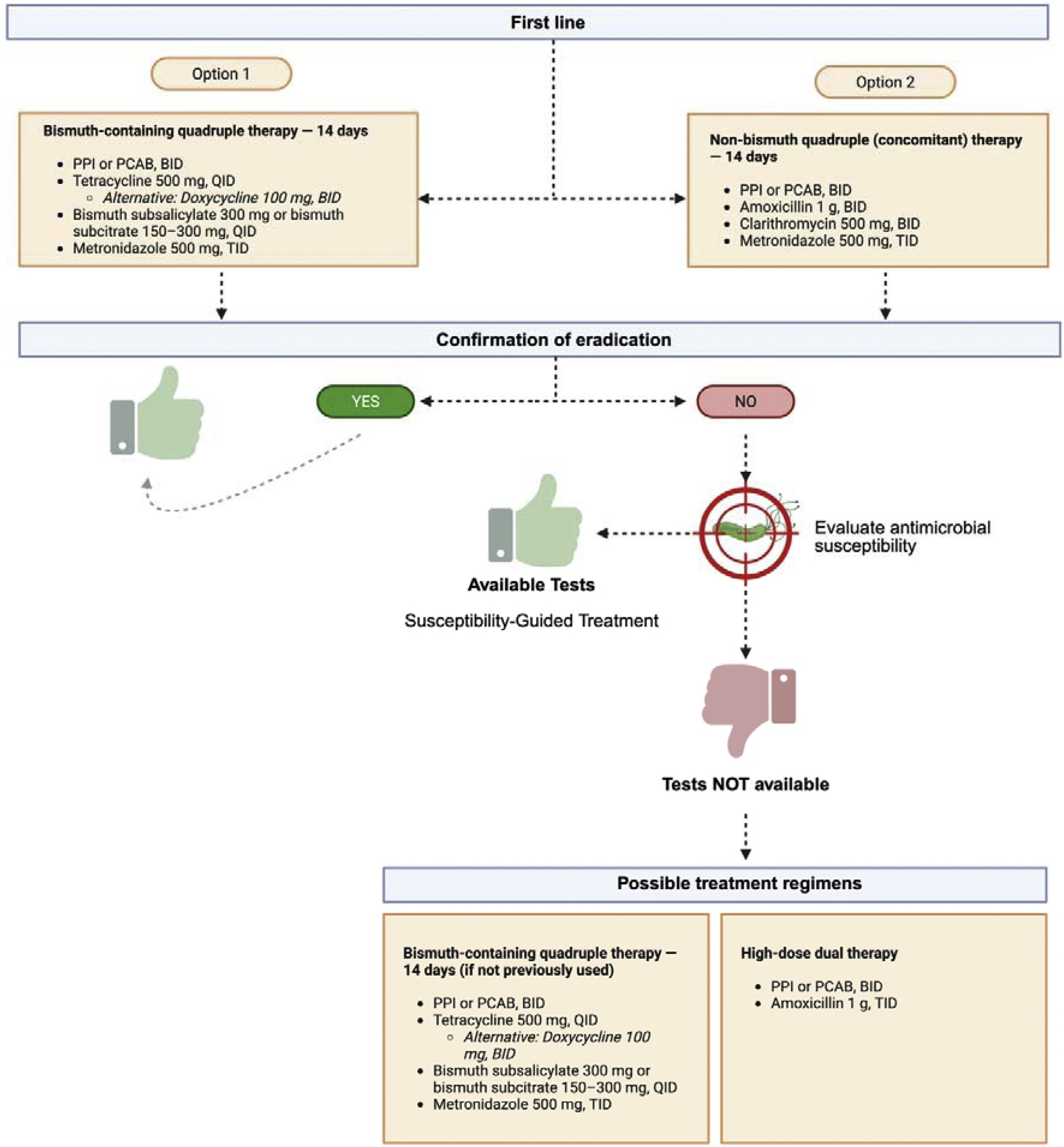

Treatment- 28

Bismuth-based quadruple therapy (BQP) (Fig. 2) administered for 14 days is the preferred option for eradicating H. pylori, especially in areas of high resistance to clarithromycin (>15%), such as Mexico. In low-resistance areas or when bismuth is unavailable, concomitant or clarithromycin-based triple therapy may be considered.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of recommendation: Strong, in favor of

In regions with clarithromycin resistance >15%, BQT (using bismuth subsalicylate or its equivalent subcitrate formulations) for 14 days is the preferred regimen, given that its efficacy is not affected by clarithromycin resistance and is less impacted by metronidazole resistance.144 When clarithromycin resistance is low or bismuth is not available, alternatives, such as concomitant therapy (PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole) may be considered; it has shown similar efficacy but may require longer treatment duration.145 In Mexico, where the abovementioned resistance threshold has been surpassed, BQT for 14 days is the recommended first-line treatment for H. pylori eradication.146–148 This regimen, composed of a PPI, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline, has shown high eradication rates, even in the presence of antibiotic resistance.146,147 Nevertheless, tetracycline availability may be limited in certain regions of the country, representing a potential barrier for the systematic implementation of said regimen.

Tetracycline is not widely available in Mexico, but doxycycline, a semisynthetic analogue with similar pharmacologic properties, is a viable and accessible alternative. Even though the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines do not strongly endorse doxycycline in H. pylori eradication regimens (based on a single study, with a very small number of patients who received doxycycline), recent studies conducted in Mexico support its use in BQT regimens.144 In particular, a real-world study compared a quadruple therapy that employed the PCAB, tegoprazan, plus bismuth, metronidazole, and doxycycline versus a traditional regimen with omeprazole as an antisecretory base.149 The results showed a 91% eradication rate in the tegoprazan group, compared with 77.7% in the omeprazole group, with no significant differences in adverse effects or adherence. This preliminary evidence suggests that, in the absence of tetracycline, doxycycline may be an effective alternative in the quadruple regimens, particularly when combined with a PCAB, such as tegoprazan. Those findings support the need for reconsidering the clinical usefulness of doxycycline when tetracycline is unavailable, especially in countries with high antibiotic resistance, such as Mexico.

If BQT is not available, concomitant therapy (PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole) may be considered, but its efficacy is more variable when there is clarithromycin resistance.146 The choice of treatment should be based on local resistance patterns, drug availability, and previous antibiotic exposure.146,147

- 29

H. pylori eradication should be demonstrated through a noninvasive method, four weeks after treatment.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Verifying H. pylori eradication is essential, given that persistent infection may lead to complications, such as peptic ulcer, gastric adenocarcinoma, and MALT lymphoma.144 In patients with dyspepsia, the absence of post-treatment symptoms does not guarantee therapeutic success, and so eradication confirmation is recommended in all cases, regardless of clinical evolution.144 Verification determines whether an alternative regimen is needed or if the approach for managing dyspepsia should be reconsidered. A negative result after treatment is encouraging, given that a meta-analysis indicated a 1% annual recurrence rate (95% CI 0.3–3) in patients in the United States.150 In addition, performing the test earlier than four weeks may yield false negatives due to transient bacterial suppression from the residual antibiotics or antisecretory effects. Confirming eradication also contributes to reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotics, thus limiting the propagation of resistant strains, providing a solid basis for further decision-making in case of failure.

- 30

Following first-line treatment failure, the regimen should be selected, taking the patient’s history, local resistance patterns, and treatment availability into account.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Management of H. pylori infection after first-line treatment failure should be based on clinical guidelines and current evidence. Previously used antibiotics should be avoided, due to the resistance risk.144,151 Of the second-line options, BQT (PPI, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline) for 14 days is highly effective. Another alternative is levofloxacin-based triple therapy (PPI, amoxicillin, and levofloxacin), particularly if levofloxacin was not used in the initial treatment and the antimicrobial susceptibility is known.144,146,152,153 In patients with multiple therapeutic failures, rifabutin-based triple therapy for 10–14 days is suggested.146,151 High-dose dual therapy with a PPI and amoxicillin for 14 days is also considered when other regimens are unsuitable.144 Treatment selection should be guided by local antimicrobial resistance patterns and the antibiotic history of the patient.144,151,154 Fourteen-day regimens are preferred for improving eradication rates.146,155 Studies indicate that BQT has higher success rates, compared with clarithromycin-based triple therapy, which is less effective as a second-line option.155

- 31

Previous exposure to clarithromycin significantly reduces the efficacy of clarithromycin-containing regimens and promotes resistance, limiting its usefulness as empiric therapy.

In complete agreement 95.8%, in partial agreement 4.2%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

Eradication rates of triple therapy with a PPI and clarithromycin have decreased over time, mainly due to the increase in clarithromycin resistance, attributed to the frequent use of macrolides in clinical practice. An RCT conducted in the United States and Europe reported a 22.2% prevalence of clarithromycin resistance.156 Despite that downward trend in efficacy, triple therapy with a PPI and clarithromycin continues to be the most widely used first-line treatment in the United States and other regions.157

- 32

Susceptibility testing, preferably molecular, should be considered before treatment in areas with high antibiotic resistance or in cases of known resistance. Such testing enables specific resistance to be identified and optimizes targeted therapy selection, improving eradication rates.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Fuerte a favor

According to expert consensus, antibiotic susceptibility testing is recommended when treatment selection is not clear, after taking into account previous treatment for H. pylori, prior antibiotic exposure in general, or a documented history of penicillin allergy.144

The molecular methods, in particular real-time PCR, whole-genome sequencing, and digital PCR, enable the detection of mutations in H. pylori associated with resistance to clarithromycin, levofloxacin, tetracycline, and rifampicin.108

Those tests can be applied as individual treatment optimization (personalized rescue therapy), as well as epidemiologic surveillance, to characterize local resistance patterns and support population-based therapeutic decisions. However, clinical availability of those tools is limited in Mexico, restricting their routine use. Their implementation should be promoted in centers of technical training, as part of surveillance and precision medicine strategies.

- 33

The 14-day BQT regimen is recommended for H. pylori eradication because it provides higher success rates compared with regimens of shorter duration.

In complete agreement 95.2%, in partial agreement 4.8%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of

The combination of a PPI, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline administered for 10 to 14 days has achieved eradication rates ≥85%, even with a high prevalence of metronidazole resistance. The 14-day regimen is generally recommended, given that metronidazole resistance is frequent and susceptibility tests are not common and sometimes have inconsistent results.108,158,159

- 34

In patients with previous treatment failures, antibiotic susceptibility testing is recommended to identify specific resistance patterns and select the most adequate treatment, optimizing eradication rates.

In complete agreement 100%

Quality of evidence: A; Strength of the recommendation: Strong, in favor of