A large part of the general population commonly uses wire bristle brushes to clean their grills. Said habit can result in the involuntary ingestion of bristles that are adhered to the food being cooked on the surface of the grill. An increase in incidence has been seen over the past 10 years, based on reports in the medical literature and data obtained from the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission.1,2

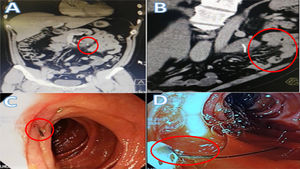

A 45-year-old man, with no known comorbidities, had a history of 2 episodes of colonic diverticulitis 4 years earlier that was treated conservatively. During a tourist trip to Argentina, he presented with postprandial stabbing pain of mild intensity at the level of the left hemiabdomen, with no other associated symptoms. Upon his return to Peru, he presented with the same abdominal pain, which became permanent and more intense. Three days later, he sought medical attention at the emergency service. Physical examination found the patient hemodynamically stable with no significant alterations. Laboratory test results were normal for the complete blood count and C-reactive protein, and an abdominal ultrasound did not aid in making a diagnosis. An abdominal tomography scan revealed the presence of an image at the level of the small bowel that was suggestive of a radio-opaque foreign body. It measured 2.50 cm in length, had pointed ends, and was embedded in the intestinal wall. An inflammatory mass was also observed at the level of the proximal jejunum (Fig. 1).

The patient immediately underwent a simple balloon-assisted anterograde enteroscopy, with laparoscopic support, that identified a wire bristle embedded in the fourth part of the duodenum. It was extracted using a biopsy forceps and the sheath of the enteroscope (Fig. 1). No type of additional surgical and/or endoscopic procedure was needed, and the 2.50 cm-long wire bristle from a brush used for cleaning grills was successfully retrieved (Fig. 2). The patient had favorable progression, with complete symptom resolution.

There are currently few studies that demonstrate the epidemiology of lesions caused by the unusual foreign body described herein.1,2 One of the most representative was the study by Baugh et al.3 that found a total of 43 cases in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database, over a 12-year period. Extrapolated to the national level, they resulted in a total of 1698 lesions registered at emergency services. The most common site of injury was the oropharynx, with 53.4% of cases (23/43), coinciding with the 30.5% (11/36) reported in the international literature, whereas the oral cavity was the predominant site found in the US Consumer Product Safety Commission database, at 37.5% (9/24). Those data reflect the low incidence rate of this type of injury in the gastrointestinal tract, of which there are only isolated reports.4,5 At present there are no international consensuses on the management of gastrointestinal injury from wire bristle grill brushes. Compromised intestinal segments that cannot be approached through conventional endoscopic techniques (middle intestine) have classically been treated through surgery.6 Nevertheless, progress in advanced therapeutic endoscopy has enabled the use of minimally invasive techniques with equal efficacy and a low complication rate. In the latest clinical guidelines from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Pennazio et al.7 established the current standards and benefits of balloon-assisted enteroscopy as first-line treatment for different small bowel disorders, which is why we first offered that type of approach to our patient. At present, there are few indications for laparoscopic support in balloon-assisted enteroscopy. It is usually carried out when there is a high probability of immediate surgical intervention during the endoscopic procedure. We utilized it due to the high risk of an increase in the size of the bowel perforation and the impossibility of effective endoscopic treatment at the time of extracting the wire bristle. Notably, given the location of the foreign body (the fourth part of the duodenum), extraction could have been performed through push enteroscopy or using a pediatric colonoscope, had balloon-assisted enteroscopy not been available, as long as the abovementioned necessary precautionary measures (laparoscopic support) were taken.

The endoscopic technique for extracting the wire bristle utilized the sheath of the enteroscope to prevent damage to the gastrointestinal mucosa, when dragging the bristle out of the area, and reduce the risk for its aspiration into the airway. It was performed following the indications in the current clinical guidelines for removing foreign bodies from the gastrointestinal tract.8,9

In conclusion, the type of injury described herein is on the rise, making it necessary to communicate preventive measures to the general population, such as avoiding the use of grill brushes that are in poor condition. Likewise, it is essential to provide the medical community with information on the new concepts related to this infrequent pathology, based on updated scientific evidence.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that no experiments were conducted on animals or humans in the present work. The clinical case was described after receiving the signed informed consent statement from the patient, which is in the possession of the corresponding author. In addition, the ethics committee of our healthcare institution approved the present study, which followed all the scientific research norms, including confidentiality of the patient data that appear in our article describing his case.

Financial disclosureNo specific grants were received from public sector agencies, the business sector, or non-profit organizations in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cedrón Cheng H, Aliaga Ramos J, Camacho Zacarias F. Manejo exitoso de perforación duodenal por cerda de alambre mediante enteroscopia anterógrada asistida con laparoscopia: reporte de caso. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2021;86:96–98.