Liver abscesses are defined as single or multiple encapsulated collections of purulent material, in the hepatic parenchyma.1 Etiology is varied and can be pyogenic and/or amoebic. Infections due to other microorganisms are less frequent. The estimated prevalence of liver abscesses is low, but according to reports in the literature, the mortality rate is high, ranging from 8 to 31%.2–3 Patient progression depends on etiology, comorbidities, and the interval of time from diagnosis to treatment. There are numerous therapeutic strategies: medical management with antibiotics, surgical drainage, and more recently, drainage through endoscopic ultrasound in selected cases,4–6 and said advances have helped decrease morbidity and mortality in those patients.

A 54-year-old woman from a rural area, with an unremarkable pathologic history, sought medical attention for pain of 10-day progression in the right hypochondrium, associated with bilious vomiting, fever, and general symptoms. The emergency room evaluation revealed fever, abdominal pain, low blood pressure, tachycardia, and hypoxemia. The patient was transferred to the special care unit to begin vasopressor support. Hospital admission laboratory test results reported elevated CRP (27 mg/dl), thrombocytopenia (77,000 mm3), elevated creatinine (5.21 mg/dl), and ureic nitrogen of 103.6 mg/dl. There was compromised liver function, with ALT 357 U/l, AST 309 U/l, total bilirubin 3.01 mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase 360 U/l, and metabolic acidemia with hyperlactatemia. An abdominal ultrasound study identified a large 10.05 × 10.21 cm hepatic lesion not suitable for percutaneous drainage due to its apparently dense consistency (Fig. 1A). The patient received support measures and empiric antibiotic treatment, but her clinical progression did not improve, and she presented with multiple organ failure involving 4 systems: renal, ventilatory, circulatory, and hematologic. Her liver profile tests revealed a cholestatic pattern, and bacteremia due to multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae was also reported. The patient had a score of 16 points on the SOFA and 36 points on the APACHE II sepsis severity scales, predicting high in-hospital mortality.

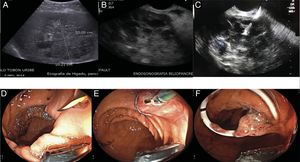

A) Hepatobiliary ultrasound identifying a liver abscess larger than 10 cm. B) Linear view of the liver abscess, through endoscopic ultrasound. C) Transgastric puncture of the abscess, D) passage of the covered metallic stent, in which drainage of abundant thick purulent material can be seen. E) Dilation of the proximal end of the stent, F) passage of the coaxial double-pigtail catheter into the metallic stent.

Due to her clinical conditions, the surgical team did not consider the patient to be a candidate for surgical drainage. A hepatic-biliary-pancreatic endosonography study was performed that ruled out choledocholithiasis and confirmed the presence of a dense, heterogeneous liver collection, 10 cm in diameter, located between segments IV-V of the liver that was suitable for endosonography-guided transgastric drainage (Fig. 1B).

The procedure was carried out, with the patient under general anesthesia. The transgastric puncture was performed using a linear echoendoscope with a 19 G (Expect™) needle, obtaining 20 ml of pus that was sent for microbiologic study (Fig. 1C). Contrast medium was then injected to delimit the collection and rule out biliary tract leakage, to then be able to introduce a fluoroscopic and endosonographic guidewire. A 0.035 mm Jagwire hydrophilic guidewire was advanced under fluoroscopic and endosonographic guidance. A Rigiflex 6 Fr cystotome was advanced over the guidewire. Using a 30 W cutting current, a tract was created and dilated, and a 10 mm × 60 mm fully covered self-expanding metallic stent was then inserted (Fig. 1D). The most proximal portion of the stent was dilated with an 8 mm CRE balloon to allow the passage of an 8.5 Fr × 7 cm coaxial double-pigtail drain into the metallic stent (Fig. 1E and F). The drainage of abundant, thick pus from the metallic stent was observed. At the end of the procedure, an endoclip was placed to fix the proximal end of the stent to the gastric wall to prevent its migration.

After the drainage, the patient’s general status improved rapidly. The inflammatory response decreased and the ventilatory and hemodynamic parameters improved, as did kidney function and coagulation. Two days after the drainage, the vasopressor and ventilatory support was withdrawn. The patient was released one week after the transgastric drainage and she completed oral antibiotic treatment in 4 weeks.

At 3 months, a control abdominal CAT scan showed complete resolution of the abscess and the presence of the metallic stent with the coaxial double-pigtail, which were then endoscopically removed with no complications (Fig. 2).

Percutaneous drainage through interventional radiology with concomitant antibiotic treatment has been the conventional approach to liver abscesses.7 Reported complications range from bleeding, needle tract infection, sepsis, hepatovenous fistula, and discomfort associated with external drainage.8 There are possible therapeutic limitations regarding both the use of stents with a maximum 12 Fr caliber in very dense abscesses and the passage of the percutaneous stent in cases involving the inferior or left segments of the liver.

Currently, transmural drainage through endoscopic ultrasound is a useful and potentially ideal option in cases of abscesses that involve the left or caudate lobe of the liver due to the fact that the transgastric approach is carried out by direct puncture under real-time vision and vascular complications are prevented through Doppler imaging at the time of the puncture. In addition, different types of metallic stents that are favorable for draining very dense or very large collections (self-expanding stents or lumen-apposing stents that have a large diameter of 10 mm–15 mm [30 Fr–45 Fr]) can be released.4,9–10

In conclusion, percutaneous drainage is the treatment of choice in liver abscesses larger than 5 cm, but there could be technical limitations in patients with abscesses in the inferior or left segments of the liver. In addition, when the material of the abscess is very thick, drainage difficulties related to the small diameters of the percutaneous stents can occur. In such a scenario, drainage utilizing endosonography-guided metallic stents can be an adequate, safe, and efficacious option for those patients.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Carvajal JJ, Betancur Salazar K, Mosquera-Klinger G. Drenaje transgástrico por ultrasonido endoscópico de un absceso hepático en paciente con disfunción multiorgánica. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2021;86:94–96.